Amadou Yaya Diallo1,2*, Fara André Sandouno1,2, Mamadou Mouctar Diallo1,2, Soriba Bangoura1,2, Kadiatou Mamadou Bobo Barry1,2, Mamadou Lamine Tegui Camara1,2, Alpha Oumar Bah1,2 and Mohamd Lamine Kaba1,2

1Service de Néphrologie - Hémodialyse CHU Donka, Conakry, Guinea

2Gamal Abdel Nasser University, Conakry, Republic of Guinea

*Corresponding Author: Amadou Yaya Diallo, Nephrologist, Service de Néphrologie - Hémodialyse CHU Donka, Conakry, Guinea.

Received: November 27, 2024; Published: December 27, 2024

Citation: Amadou Yaya Diallo., et al. “Therapeutic Pathway and Quality of Care for Patients Suffering from Chronic Renal Failure in the Donka University Hospital Nephrology Department". Acta Scientific Paediatrics 8.1 (2025): 09-15.

Introduction: The aim of this study was to evaluate the therapeutic pathway and quality of care of patients suffering from chronic renal failure at the Donka University Hospital Nephrology Department.

Material and Methods: This was a prospective analytical study conducted over a period of six (6) months, from 1 November 2022 to 31 April 2023, and included patients of all ages with chronic renal failure and a creatinine clearance of less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m² who agreed to take part in the study.

Results: During the course of the study, we recorded 142 cases, of which 98 (69%) were CKD patients. The mean age of our patients was 47.5 years, with a predominance of women in 52 cases (53.1%) and a sex ratio of 0.9. The most common reasons for consultation were disturbance of renal function 98 cases (100%) and arterial hypertension (AH) 97 cases (98.98%). Vascular nephropathy (39.8%) and glomerular nephropathy (35.7%) were the most common. Stage 5 CKD was most common in 91 cases (92.9%). In our study, hypertension 94 cases (96%) and herbal medicine 70 cases (87.5%) correlated significantly with the onset of chronic kidney disease with a p-value of 0.001. All patients had received antihypertensive drugs, antianaemic drugs and calcium plus vitamin D.

Progress was favourable in 86 cases (87.8%).

The majority of patients were satisfied with the quality of care in 55 cases (56%) compared with 43 cases (44%) who were dissatisfied.

Conclusion: A larger study could provide a better view of the impact of the therapeutic pathway and quality of care in CKD patients.

Keywords: Treatment; Quality of Care; Chronic Kidney Disease; Donka

Chronic renal failure is defined as a lasting reduction in glomerular filtration rate associated with a permanent and definitive reduction in the number of functional nephrons. It is said to be chronic when it has been present for at least 3 months [1]. This pathology is common, affecting 8 to 16% of the world's population, of whom around 0.5% will progress to end-stage renal failure. It is the 9th leading cause of death in developed countries [2].

As a result, chronic kidney disease is a major public health problem worldwide. The true extent of the disease in Africa remains unknown [3], and it is a long silent disease with a progressive course and, in the majority of cases, no cure [4].

Diabetes, hypertension and obesity are the leading causes of CKD in developed countries [5], while in developing countries the majority of CKD is of mixed origin, combining a complication of a communicable disease with that of a chronic non-communicable disease [6].

The care pathway can be defined as ‘the overall trajectory of patients and users in a given healthcare area, with particular attention paid to the individual and his or her choices’ [7], and must be ‘the right sequence, at the right time, of these different professional skills linked directly or indirectly to care: consultations, technical or biological procedures, medicinal and non-medicinal treatments, and social care’. The care pathway for patients with chronic kidney disease is based on a sequence of different stages that depend on the progression of CKD, the patient's choices and the occurrence of health events [8].

According to the WHO, quality care is effective, appropriate, safe, accessible, acceptable, and the least costly to the patient [9]. Quality of care means legitimacy of care, justification of care provided, access to care and social justice, continuity of care, but also management of care staff [10]. Quality of care is the ability to meet the implicit and explicit needs of patients, according to the professional knowledge of the time and according to the resources available [11].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the therapeutic pathway and quality of care of patients suffering from chronic renal failure in the Donka University Hospital Nephrology Department.

This was a prospective analytical study conducted over a period of six (6) months from 1 November 2022 to 31 April 2023. Patients of any age with chronic renal failure and a calculated creatinine clearance of less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m² who agreed to take part in the study were included in the study. Acute renal failure and chronic kidney disease patients with a GFR greater than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 were not included.

Our variables were quantitative and qualitative, broken down into :

Urea, creatinine, CBC, blood calcium, viral serologies (HIV, HCV, HBV) and urine dipstick.

Ultrasound of the kidneys (kidney size, corticomedullary differentiation), fundus: to look for retinopathy.

Stage of CKD (stage 3A, stage 3B, stage, stage 5).

Vascular nephropathy, glomerular nephropathy, chronic interstitial nephropathy, diabetic nephropathy, dominant polycystic kidney disease, undetermined nephropathy and mixed nephropathy.

Drug treatment, haemodialysis.

Quality of care received: satisfied, dissatisfied.

Evolution: were divided into,

Data were collected using a pre-established survey form, validated and entered into Word and Excel, then analysed using Epi Info version 3.5.3 software.

The agreement of the department managers was obtained before the start of the investigations. A working protocol was drawn up and validated by the hospital authorities and the Chair of Nephrology. Free and informed consent was obtained from the patients included in this study, respecting confidentiality and anonymity in accordance with medical ethics.

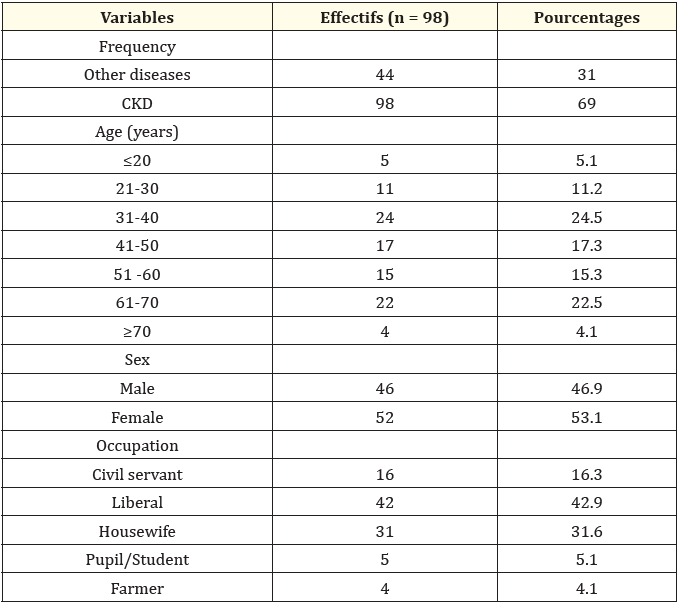

During this study period, we recorded 142 cases, of which 98 (69%) were CKD. The mean age of our patients was 47.5 years, with a predominance of females in 52 cases (53.1%) and a sex ratio of 0.9.

The most common socio-professional groups were professionals (42.9%) and housewives(31.6%) (Table 1).

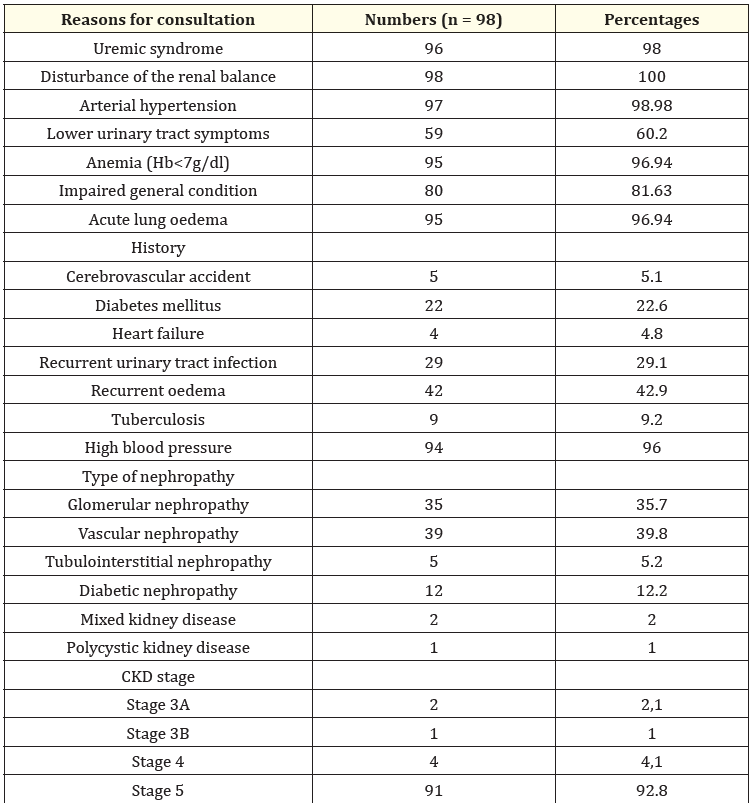

The most common reasons for consultation were disturbance of the renal balance 98 cases (100%) and hypertension 97 cases (98.98%). According to history, arterial hypertension 94 cases (96%), oedema of the lower limbs 29 cases (42.9%) and diabetes mellitus 22 cases (22.5%),

Vascular nephropathy 39 cases (39.8%) and glomerular nephropathy 35 cases (35.7%) were the most common types of nephropathy.

According to the progressive stage of CKD, 91 cases (92.9%) were at stage 5 (Table 2).

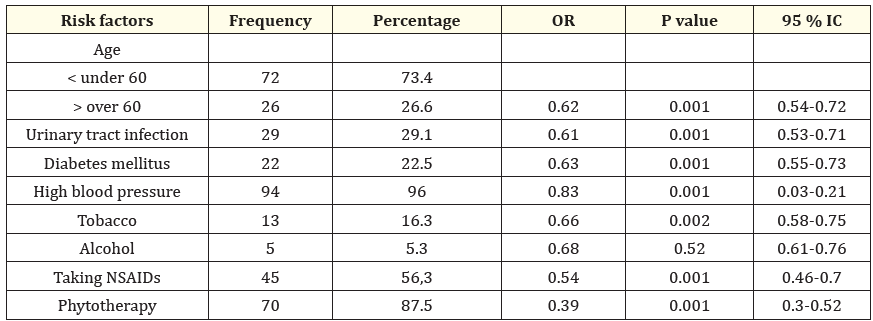

Risk factors were dominated by hypertension in 94 cases (96%) and herbal medicine in 70 cases (87.5%) with a p-value of 0.001.

Biologically, 59 patients (62.1%) had haemoglobin levels between 6 and 9 g/dl and 22 patients (23.2%) had Hb levels ≤ 6g/dl. Hypocalcaemia was found in 61 cases (80.3%).

Proteinuria was found in 61 cases (62.24%), haematuria in 40 cases (40.84%) and leucocyturia in 35 cases (35.71%). Renal ultrasound abnormalities were dominated by renal atrophy in both kidneys, with frequencies of 47 cases (58.8%) and 42 cases (52.5%) respectively.

All of the patients had received antihypertensive medication, anti-anaemia medication and calcium plus vitamin D. Only 30 cases (30.6%) had received haemodialysis, compared with 68 cases (69.4%) who had not been dialysed.

Progression was favourable in 86 cases (87.8%) compared with 12 cases (12.2%).

The majority of our patients were satisfied with the quality of care in 55 cases (56%) compared with 43 cases (44%) who were not.

Table 1: Breakdown of patients by socio-demographic characteristics

Table 2: Distribution of patients according to clinical data, history, type of kidney disease and stage of CKD progression.

Table 3: Distribution of patients according to risk factors for chronic renal failure.

During the study period, we recorded 142 cases, of which 98 (69%) were CKD. This result is similar to that of Amekoudi EY., et al. in Togo in 2016, who reported 71.4% [12], but our result is higher than that of Bah ML., et al. in 2021 in Guinea, who found 31.9% [13].

The mean age of our patients was 47.5 years. Our result is different from that reported by Mahoungou G., et al. [14] in 2021 in Congo Brazzaville who found an average age of 51.9 years but lower than that of Bah ML., et al. in 2021 in Guinea who found 60.94 years [13].

Females predominated in 52 cases (53.1%) with a sex ratio of 0.9. Our results are similar to those of Taleb S., et al. in Algeria in 2016 and Bah M., et al. in Guinea in 2021, who reported a predominance of females, respectively 54.9% and 56.7% with a sex ratio of 0.8 [13,15]. These results differ from those reported by Daroux M., et al. Lagoud D., et al. and Jungers P., et al. who reported a male predominance with a sex ratio of 1.3 to 2.9 [16-18].

The most represented socio-professional group was professionals in 42 cases (42.9%), followed by housewives in 31 cases (31.6%). Our results were similar to those of BAH M., et al. in Guinea in 2021, who reported a predominance of housewives (42.6%) and professionals (31.21%) [13].

The most common reasons for consultation were renal dysfunction in 98 cases (100%) and arterial hypertension in 97 cases (98.98%). This result can be explained by the fact that the finding of a rise in plasma creatinine prompts practitioners to refer patients to the nephrology department for specialised treatment [19].

According to the antecedents, arterial hypertension 94 cases (96%), oedema 29 cases (42.9%) and diabetes mellitus 22 cases (22.5%) were the most prevalent. This result corroborates that reported by BAH M., et al. in Guinea in 2021, who found that 73% of their patients had a history of hypertension and 27.7% had diabetes [13].

The risk factors for chronic kidney disease were dominated by hypertension in 94 cases (96%) and herbal medicine in 70 cases (87.5%) with a p-value of 0.001. These data differ from those of Fofana F., et al. in Guinea, who reported the use of NSAIDs in 28.9% of cases, repeated urinary tract infections in 24.4% and herbal medicine in 15.6% of cases [20].

Biologically, 59 patients (62.1%) had a haemoglobin level of between 6 and 9 g/dl and 22 patients (23.2%) had an Hb level ≤ 6g/dl. Our results corroborate those of Stengel B., et al. in France in 2007 who reported that 91.4% of their subjects had an Hb level <10g/dl [21]. 61 cases (80.3%) were hypocalcaemic. This may be due to the fact that blood calcium levels in CKD patients are low, except in the case of myeloma, where hypercalcaemia is observed even in the terminal stage.

In this study, stage 5 CKD was most common in 91 cases (92.9%). This result is much higher than that reported by BAH M., et al. in Guinea in 2021 in the internal medicine department of CHU Donka, which found 60.99% of cases at stage 3 and 6.38% at stage 5 [13]. This difference can be explained by the fact that most patients are admitted at an advanced stage of the disease and by the lack of early detection of kidney disease.

According to the urine dipstick, we noted proteinuria in 61 cases (62.24%), haematuria in 40 cases (40.84%) and leucocyturia in 35 cases (35.71%).

According to the initial nephropathy, vascular nephropathy in 39 cases (39.8%) and glomerular nephropathy in 35 cases (35.7%) were the most common. Our results were similar to those of Tia WM., et al. in Côte d'Ivoire at the CHU of Bouaké in 2022 who reported 34.66% vascular nephropathy and 29.33% glomerular nephropathy [22].

Renal ultrasound abnormalities were dominated by renal atrophy in both kidneys, with frequencies of 47 cases (58.8%) and 42 cases (52.5%) respectively. These results can be explained by the fact that kidney size is generally reduced in CKD, with the exception of renal amyloidosis, hydronephrosis, diabetes and HIV in CKD [23].

According to the HAS, the treatment objectives included in the CKD care pathway consist primarily of slowing the progression of kidney disease, treating the causative disease, preventing cardiovascular risk and preventing complications of CKD [24].

Treatment in our study was essentially symptomatic. All patients had received antihypertensive drugs, antianemics and calcium plus vitamin D. Treatment of hypertension included diuretics, ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers. This is in line with the new recommendations for the treatment of hypertension in CKD patients [25].

Only 30 cases (30.6%) of our patients had received haemodialysis. No patient had undergone peritoneal dialysis or renal transplantation. These two techniques are not yet available in our country.

During our study period, 86 cases (87.8%) of our patients had a favourable outcome. Our results were similar to those of Bah ML., et al. who reported that 87.2% of their patients had a favourable outcome [13].

The majority of our patients were satisfied with the quality of care in 55 cases (56%) compared with 43 cases (44%) who were not.

Chronic renal failure is a chronic progressive disease which remains silent for a long time. It requires supplementary treatment by dialysis or renal transplantation. Females were more commonly represented, and the most common reasons for consultation were disturbed renal function tests and arterial hypertension. Stage 5 CKD was the most common, with risk factors dominated by hypertension and herbal medicine.

All our patients benefited from antihypertensive drugs, anti-anaemia drugs and calcium plus vitamin D.

More than half our patients had a favourable outcome. The majority of our patients were satisfied with the quality of care they received.

A larger study could provide a better picture of the impact of therapeutic treatment and quality of care in CKD patients.

All authors participated in data collection, analysis and writing of the manuscript. The manuscript was read and accepted by all authors.

Copyright: © 2025 Amadou Yaya Diallo., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.