Tanishq Mahajan1, Dhruvendra Lal2*, Aman Bharti3, Amaneet Kaur1, Poonam Bharti4, Kavisha Kapoor Lal5

1Postgraduate student, Department of Psychiatry, Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, MMDU, Ambala, Haryana, India

2Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Dr B R Ambedkar State Institute of Medical Sciences, SAS Nagar, Mohali, Punjab, India

3Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Guru Gobind Singh Medical College, Faridkot, Punjab, India

4Head, Department of Psychiatry, Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, MMDU, Ambala, Haryana, India

5Assistant Professor, Department of Periodontics, Himachal Dental College, Sundernagar, HP, India

*Corresponding Author: Dhruvendra Lal, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Dr B R Ambedkar State Institute of Medical Sciences (AIMS) , Mohali, Punjab, India.

Received: March 06, 2024; Published: March 20, 2024

Citation: Dhruvendra Lal., et al. “ECG Abnormalities in Patients on Psychotropics Medications: A Prospective Observational Study”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 7.4 (2024): 20-28.

Objectives: Patients with mental illness are at an increased risk of cardiovascular changes, which can lead to mortality, and the use of psychotropic medications can exacerbate these risks. Various types of psychotropic drugs can have anticholinergic and antimuscarinic effects, leading to sinus tachycardia, while SSRIs may cause mild bradycardia. Tricyclic antidepressants can prolong the QRS interval and cause conduction defects, which is especially harmful for those with preexisting cardiac conduction delay and can lead to heart block.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the diverse ECG changes among outpatients who had been taking psychotropic medications for over a year and their association with other variables.

Material and Methods: A prospective observational study with patients on psychotropics for more than one-year was conducted in a tertiary care hospital.

Results: 125 psychiatric patients of which 53.60% (n = 67) were males and 46.40% (n = 58) were females. It was observed that out of 65 participants on antipsychotics 15.38% had abnormal ECG (Electrocardiogram) whereas among 60 participants on antidepressants 13.33% showed abnormal ECG. It was also seen that of 120 patients on benzodiazepine, 16.67% had ECG changes. Patients on psychotropics other than the above mentioned were 63 in number and constituted 20.63% of abnormal ECG changes.

Conclusion: ECG changes were observed in 15% to 20% of the patients who were started on psychiatric medicines. The changes were more among participants on antipsychotics (19.1%) followed by benzodiazepines (15.4%).

Keywords: ECG; Psychotropic; Antipsychotics; Medication; Cardiac Manifestation; Side Effects

SSRI: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; ECG: Electrocardiogram; TCA: Tricyclic Antidepressants; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; QTIP: QT Interval Prolongation; SCD: Sudden Cardiac Death

Patients with mental disorders are considered to have a higher likelihood of experiencing cardiovascular changes compared to the general population [1]. Additionally, they are at an increased risk of mortality due to adverse effects of psychotropic medications. As a result, there is growing concern about the cardiac safety of these drugs [3,4].

Psychotropic drugs (including typical, atypical antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, non-selective monoamine oxidase and all anti parkinsonian anticholinergics) have anticholinergic as well as antimuscarinic effects and can lead to sinus tachycardia [5,6]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) typically cause mild bradycardia, while tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can lead to conduction defects and prolong the QRS interval. These effects are dependent on the dosage of the medication [7,8]. These findings are particularly dangerous for patients with preexisting cardiac conduction delays and can potentially result in varying degrees of heart block [9].

There is variation in the capacity of antipsychotic to cause QTc prolongation [10].

Low-potency typical antipsychotics are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular changes, while high-potency typical and atypical antipsychotics less frequently cause torsades de pointes, except for ziprasidone, which has led to a debate within the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), resulting in a delay in approval. The most significant concern lies with the immediate use of haloperidol and the long-term use of olanzapine and clozapine [11].

Patients with psychiatric illness are subjected to polypharmacy [12,13], illicit drug use, high drug dosage which increases the risk of QTc prolonging drugs and QT drug-drug interaction [14,15]. In addition, QTIP (QT Interval Prolongation) is due to combined use of antipsychotic and antidepressants in most clinical settings [13,16]. The increased use of polypharmacy, increased doses, combination drugs with poor health care increased risk of QTIP related mortality and morbidity [17-19].

Secondary TCA affect children and elderly more whereas tertiary TCA affect entire general population. Mirtazapine is the only antidepressants that has been reported to have caused torsade’s de pointes among other antidepressants. SSRI have no effects on QTc. Similarly, benzodiazepine have little effect on QTc but they can have effects on other cardiovascular parameters [11].

Oher risk factors for QT prolongation and torsade’s de pointes in psychiatric population include, substance use, accidental or deliberate overdose and restrain that leads to high sympathetic arousal.

The aim of this study was to determine varied ECG changes among outpatient who have been on long term use of psychotropic medications (more than one year) and its association with other variables like sociodemographic profile, comorbidities and vitals.

A prospective observational study was conducted at the psychiatry outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital, using convenience sampling, to include patients more than 18 years of age diagnosed with psychiatric disorder, of either gender. The duration of the study was for one year, from 01.10.2020 to 30.09.2021.

The study was ethically approved by the ethical committee of Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Mullana, Ambala vide project number IEC-1775 dated 14.09.2020. Prior to participation a written consent was taken from all the participants.

Patient’s medical profile was checked for presence of any cardiac abnormalities and the ones with no prior history of any cardiac illness were included in the study. Electrocardiogram (ECG) was done for the ones included in the study. Demographic and medical history was collected from each participant for analysis.

The results have been expressed as frequencies and percentages. Association has been calculated using Chi Square test at 95% confidence interval p value of less than 0.05 has been considered as significant.

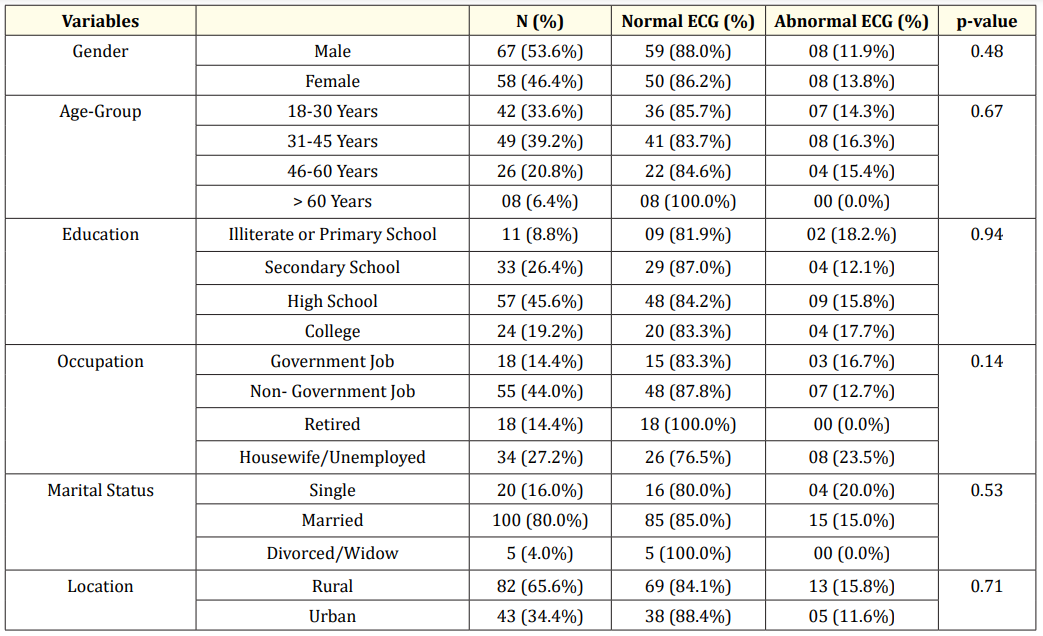

Table 1: Relationship between Sociodemographic variables and ECG changes.

This study included 125 psychiatric patients of which 53.6% (n = 67) were males and 46.4% (n = 58) were females. Table 1 shows that abnormal ECG changes were almost same in both males and females which was 11.9% (n = 08) and 13.8% (n = 08) respectively. Majority of participants were from the age group 31 to 45 years constituting 39.2% (n = 49) and abnormal ECG in them was seen in 16.3% (n = 8) individuals. In education status majority of the participants were high school pass outs 45.6% (n = 57) and ECG abnormalities were also seen majorly in them 15.8% (n = 9). Patients with non-government job constituted 44% (n = 55) and had abnormal ECG of 12.7% (n = 7). In this study majority of the participants were married 80.0% (n = 100) among them abnormal ECG was in 15.0% (n = 15). Patients from rural location constituted 65.2% (n = 82) among which 15.8% (n = 13) showed abnormal ECG.

When the ECG changes were compared among various comorbidities including those without any comorbidity and it was seen that abnormal ECG changes were more in those with anemia 100.0% (n = 1) followed by those with hypothyroidism 40.0% (n = 4), arthritis 33.3%(n = 3), diabetes mellitus 25.0% (n = 2), whereas 20.0% (n = 25) of abnormal ECG changes were also recorded among those with no co-morbid abnormalities (Figure 1).

Figure 1: ECG changes among patients with various co-morbidities.

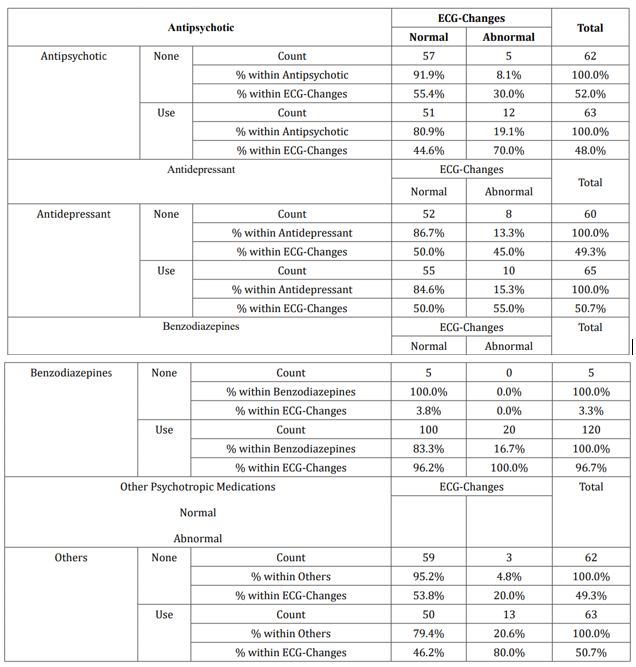

Of 65 participants on antipsychotics 15.4% had abnormal ECG whereas among 60 participants on antidepressants 13.3% showed abnormal ECG. It was also seen that of 120 patients on benzodiazepine 16.7% has ECG changes. Patients on psychotropics other than the above mentioned were 63 in number and constituted 20.6% of abnormal ECG changes (Table 2).

Table 2: Relationship between Psychotropic Drugs and ECG-Changes.

Abnormal ECG was seen in those with low pulse rate 71.4% (n = 5) followed by those with high pulse rate 22.6%(n = 12). Among blood pressure parameter abnormal ECG was seen in normotensives 50.0% (n = 4) followed by those with hypertension 17.0% (n = 8). Patients with height ranging from 165 to 175 cm had abnormal ECG 16.7% (n = 5) followed by those with height with 155 to 165cm 13.2% (n = 9). Those patients with weight between 55 to 65 kgs had abnormal ECG 18.3% (n = 9). It was also seen that patients with obesity had abnormal ECG 33.3% (n = 1) followed by those patients with normal ECG 15.8% (n = 15) (Table 3).

Table 3: General physical parameters and ECG changes.

Among the ECG changes, sinus tachycardia had a prevalence of 8.0%, that of sinus bradycardia was 3.0%. Prevalence of prolonged PR interval was 1.0% and that of sinus arrhythmia was 1.0% (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of various ECG changes among patients.

The study conducted to find ECG abnormalities (QTc interval and other related variables) in patients on psychotropics medications for finding is in particularly harmful for those with preexisting cardiac conduction delay and can lead to heart block in varying degrees. There is 125 patients came under this study a prospective observational study was conducted at the psychiatry OPD of a tertiary care hospital. The convenience sampling was used to include patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorder, who had been on psychotropics for >1 year, aged above 18 years or more, of either gender from 20th September 2020 to 20th March 2020.

A previous study had limitations due to its cross-sectional observational nature, which prevented drawing conclusions regarding the causation of ECG abnormalities related to mental illness versus psychotropic medication use. Factors such as medication adherence, duration of mental illness, and pharmacological treatment were also not taken into consideration. Future large prospective studies are recommended to address all of these issues, including the relationship between ECG changes and sudden cardiac death in patients who use antipsychotics and other psychotropic medication [22].

In general, the use of buprenorphine is not associated with QTc interval prolongation as a side effect, unlike other narcotics. Studies have found that buprenorphine is less likely to cause QTc interval prolongation than methadone [23].

Some studies have found that the use of buprenorphine can still result in an increase in QTc interval, even though it is generally considered less likely to cause this effect than other narcotics. The workgroup reviewing this issue has chosen to focus only on studies involving adults over the age of 18, as there are limited studies evaluating the effects of psychotropic medications on QTc interval prolongation in children and adolescents. It is important to conduct additional research in this population to guide clinical decisionmaking and prevent overly cautious interpretations of ECGs that may lead to undertreatment [24,25]. Extrapolation of data from adults to children and adolescents is not always appropriate, as there may be differences in how medications affect these populations. For example, while there is limited data on the use of psychotropic medications and QTc interval prolongation in children and adolescents, there are some studies on the use of methadone in these populations that suggest it may be safe. However, additional prospective data are needed to confirm these findings and guide clinical decision-making [26,27]. Antipsychotic medications have received the most attention in the pediatric population when it comes to evaluating their effects on QTc interval prolongation. A systematic review of the available data found that ziprasidone was associated with the greatest degree of QTc interval prolongation, while aripiprazole was found to reduce QTc interval to a significant extent. These findings are consistent with studies conducted in adults [28]. The use of antipsychotic medications or other medications that may prolong the QTc interval in the context of eating disorders requires specific consideration, especially in patients with anorexia or bulimia who may be predisposed to bradycardia and/or electrolyte abnormalities. Correction equations may underestimate the true severity of repolarization abnormalities, so additional monitoring and repeat ECGs are recommended when medications posing a risk for QTc interval prolongation are added or doses are adjusted [19].

This study involved collecting data through repeated measurements of QTc at the time of admission. Socio-demographic factors were also taken into account. The results showed that abnormal ECG readings were more common among female patients, individuals aged 31-45 years, and those with a higher level of education (i.e., graduates or post-graduates). The occupation most commonly associated with abnormal ECGs was housewife or unemployed. Additionally, single patients were more likely to have abnormal ECG readings compared to those who were married or in a relationship. Lastly, patients from rural areas had a higher incidence of abnormal ECGs than those from urban areas.

Anaemia and hypothyroidism are two major comorbidities that can significantly affect ECG readings. Additionally, conditions such as arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension have also been found to impact ECG results. The use of psychotropic drugs has also been linked to changes in ECG readings, with antipsychotic drugs showing the highest percentage (19.05%) of patients with ECG changes. Antidepressants and benzodiazepines were associated with 15.3% and 16.7% of patients with ECG changes, respectively. Other types of drugs were also found to cause ECG changes, with a percentage as high as 20.6% of patients affected.

For several years, antidepressants belonging to the SSRI class were deemed safe in terms of prolonging the QTc interval, despite sporadic case reports of QTc interval prolongation for all agents in this category. Currently, studies investigating the effects of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine on QTc interval prolongation have yet to provide conclusive evidence of such a phenomenon [30]. Sertraline remains the agent with the best-established track record in cardiac populations [31,32]. The FDA warning for QTc interval prolongation with citalopram, which was issued in August 2011, was based on a thorough QTc interval study that showed an increase in QTc interval of 8.5ms at doses of 20mg and 18.5ms at doses of 60mg [33]. Despite some occasional case reports of QTc interval prolongation for all agents in the SSRI class, studies examining the QTc interval prolongation effect of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine have not found compelling evidence of such an effect. However, subsequent research, including a meta-analysis, a large retrospective study of an ECG database, and a randomized placebo-controlled study, have suggested that citalopram may be more likely than other SSRIs to cause QTc interval prolongation, and may prolong the QTc interval at a similar magnitude to that demonstrated in the FDA study [34-37]. It is important to note that despite the FDA recommendation, some practitioners may still use doses of citalopram higher than 40mg in certain cases, depending on individual patient factors and risk-benefit considerations. Close monitoring of ECG and other relevant parameters is essential when using citalopram or any medication that may prolong QTc interval, and caution should be exercised when using these medications in patients with known risk factors for QTc interval prolongation. In addition, patients should be educated on the signs and symptoms of QTc interval prolongation and advised to seek medical attention if these occur. Overall, the decision to use citalopram or any medication should be made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the individual patient’s clinical presentation and risk factors [38].

Our study examined 65 participants on antipsychotics and found that 15.4% had abnormal ECG results. Among 60 participants on antidepressants, 13.3% showed abnormal ECG results. Furthermore, of the 120 patients on benzodiazepines, 16.7% had ECG changes. Finally, the 63 patients on other psychotropic medications constituted 20.6% of abnormal ECG changes. Comparing these results to other studies, we can conclude that the rate of abnormal ECG changes among patients on antidepressants is similar to that of other psychotropic medications.

In our study, we compared ECG changes between participants with different comorbidities and those without any comorbidity. The results showed that participants with anemia had the highest incidence of abnormal ECG changes at 100.0%, followed by those with hypothyroidism at 40.0%. Among patients who were started on various psychiatric medicines, ECG changes were observed in 15.0% to 20.0% of them. Specifically, those on antipsychotic drugs had the highest incidence of ECG changes at 19.1%, followed by benzodiazepines at 16.7%, and antidepressants at 15.4%.

None.

The study obeys the ethical principles as laid down in the Helsinki declaration and was ethically approved by the ethical committee of Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Mullana, Ambala vide project number IEC-1775 dated 14.09.2020. Prior to participation a written consent was taken from all the participants.

Not Applicable.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The authors received no external funding for the design of the study, for the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or for writing the manuscript.

Copyright: © 2024 Dhruvendra Lal., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.