Akash Daddanala1, Khushi Sitapara1, Manasa Veena Madala1*, Manognya Pravallika Ambatipudi1, Rishabh Singh Kalra1 and Maitreyi Shekhar Mahajan2

1Junior Resident, Department of Public health dentistry, Sri Sai College of Dental Surgery, Vikarabad, Telangana, India 2Junior Resident, Faculty of Dental Sciences, MS Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences, SDM Dental College and Hospital, India

*Corresponding Author: Manasa Veena Madala, Junior Resident, Department of Public health dentistry, Sri Sai college of dental surgery, Vikarabad, Telangana, India.

Received: February 26, 2024; Published: February 28, 2024

Citation: Manasa Veena Madala., et al. “Psychological Distress Experienced by Parents of Special Child in Hyderabad City-A Cross Sectional Study”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 7.3 (2024): 56-64.

Background: Parents of children with intellectual disabilities are constantly under stress due to the challenging nature of raising them. Thus, the aim of this study is to evaluate the psychological stress faced by the parents of special children.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study that was carried out in the various schools for special children in and around the city of Hyderabad in March 2023. Abedin’s Parenting Stress Index (short form) was used, and the questionnaires were distributed among 265 parents and carers of special children. Using the collected data, descriptive statistics, frequency distribution, Pearson’s correlation, and multiple linear regression analysis were done.

Results: When categorized under mild, moderate, and high-stress level groups, 90 parents out of 265 were in the low-stress, 87 under moderate stress, and 88 under the high-stress level group. A significant correlation was observed between stress among parents of special children the education status of the parent (P < 0.05) and the duration of disease since diagnosis in the child (P < 0.05).

Conclusion: The study concluded that the majority of the parents are in psychological distress.

Keywords: Psychological Distress; Parental Distress; Special Kids; Parental Stress Index; Difficult Child; Intellectual Disability

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines an individual with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment [1]. One such disability is intellectual disability (ID), which affects the cognitive functioning and skills of a person. According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), “intellectual disability” is a condition characterised by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour that originates before the age of 22 years [2].

A few examples of intellectual disabilities include autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cerebral palsy, ADHD, epilepsy, impulse control disorder, depression, and anxiety disorder. ID is a multifactorial disease where the commonly known preventable or environmental factor is foetal alcohol syndrome, while the most common chromosomal cause is Down syndrome, and genetically, it is caused by fragile X syndrome.

In a survey done by Ram Lakhan, Mohammad Shahbazi., et al. in 2015 reported that the prevalence of intellectual disability in developing countries like India is varied by age, gender, population type, and place of residence. The overall ID prevalence was reported to be 10.5/1000 in India [3]. Children with special needs may have developmental delays, medical conditions, psychiatric conditions, and/or congenital conditions because of which they require extra care and attention to reach their maximum potential, the burden of which falls on the carers or parents.These hindrances can lead to various psychological, financial, social, and emotional burdens that in turn, cause a lot of stress among the parents or caregivers. According to the WHO, stress can be defined as a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation. Stress is a natural human response that prompts us to address challenges and threats [4]. Parental stress is the distress experienced by parents when they feel that they can’t cope as parents because the demands being placed on them are too high and they don’t have the resources to meet them (Deater-Deckard 1998; Holly., et al. 2019) [5]. The parental stress scale (PSS) given by Judy Berry and Warren Jones (1995) and the parental stress index (PSI) given by Abidin, R.R. (2012) are widely used scales to measure the stress experienced by the parents. The short form of the PSI, which contains 36 questions also gives an in-depth analysis of parental stress.

Compared to developed countries, in a developing country like India, the scenario of parenting lacks adequate support from the government authorities and inadequate support from the family and society add on to the burden faced by the parents of a special child. Most of the time, they are apprehensive about getting out and socializing, with a fear of being judged by society. These parents are still frowned upon or looked down on in some parts of the country, which can often lead to psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, etc. As there are not many studies that focus on the stress levels and mental well-being of the parents of a special child, the aim of this study is to evaluate the psychological stress faced by parents of special child in the city of Hyderabad, India.

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the psychological stress experienced by parents of children with special needs in Hyderabad. The study was carried out with parents of children enrolled in special schools in Hyderabad city. Hyderabad city is segmented into five zones: North, South, Central, East, and West. The DEO provided a comprehensive list of schools in these zones. There are 110 special schools in Hyderabad city. Initially, three schools were randomly selected from each zone using a simple random lottery method to collect the sample. Abidin’s (1995) Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI/SF) was used to assess the psychological stress experienced by parents of children with special needs. The PSI/SF is a 36-item scale that strongly correlates with the fulllength PSI in total stress, parent domain (PD), child domain, and PCDI. The questionnaire comprises three sections: parental distress (PD), parent-child dysfunctional interaction (P-CDI), and difficult child (DC). Each of these comprises a series of 12 questions. The response was evaluated based on the Likert scale, with options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Demographic information such as the child’s age, parent’s age and gender, parent’s education level, marital status, occupation, head of family’s marital status, total family members, number of siblings, child’s birth order among siblings, child’s diagnosis, duration of child’s illness since diagnosis, any systemic illness in the parent, and the 2022 Modified Kuppuswamy Socio-Economic Scale were collected to determine the socio-economic status.

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board of a dental institution in Vikarabad (approval number: 05/SSCDS/ SS/IRB/2022) and permissions were secured from the relevant schools. A pilot study was conducted among 30 parents of special needs children from two schools that were not part of the main study. This was conducted to assess the feasibility and clarity of the questionnaire and to establish the final sample size. The final sample size of 265 was determined based on the mean score obtained from the pilot. Parents provided informed consent after a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose. Data collection was planned to take place from January 1 to March 31, 2023, spanning a period of 3 months. The authorised special schools were contacted. School principals were asked to organise a parent-teacher meeting on the specified dates to attract many attendees. The primary investigator distributed the questionnaires to the parents, allowing them sufficient time to complete them before collecting them on the same day. The primary investigator conducted individual interviews with parents who were unable to read or write English, and recorded their responses to the questionnaire. The gathered data was verified for completeness and inputted into an Excel spreadsheet. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 20.0. The confidence interval was established at a 95% level. A P value of 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Analysed data using descriptive statistics, frequency distribution, Pearson’s correlation, and multiple linear regression.

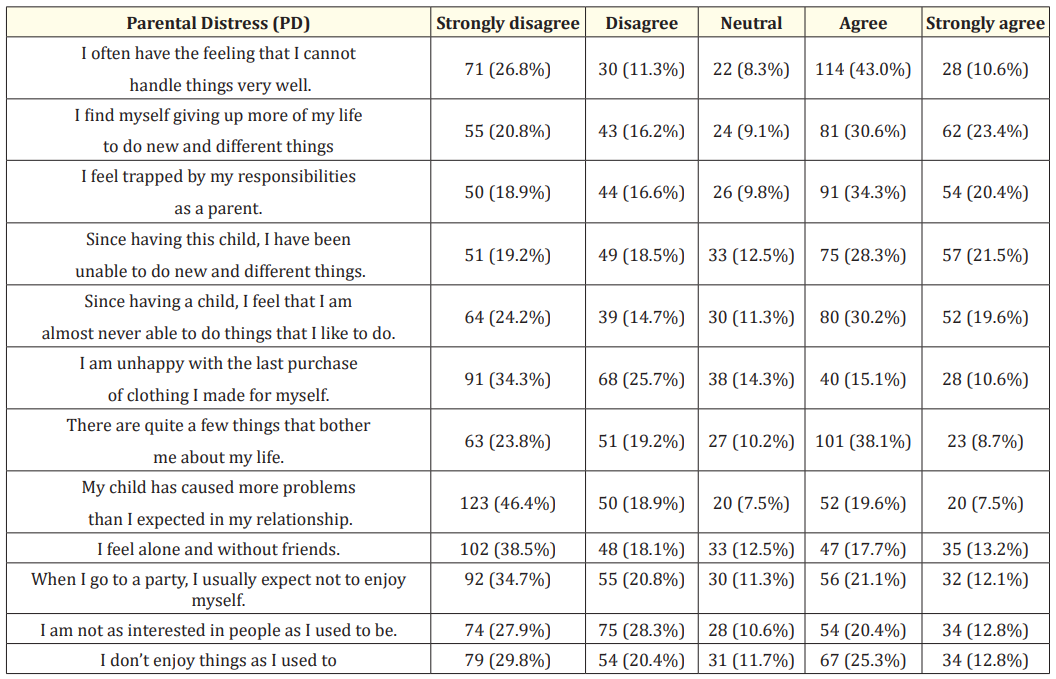

The parental distress (PD) experienced by the parents showed that 43% of them agreed that they could not handle things very well, and since having the child, 30.2% agreed that they were never able to do the things that they liked. 34.3% of them agreed that they feel trapped in their responsibilities as parents, but contradicting this, 46.4% of them strongly disagreed that their child had caused more problems in their relationship. Moreover, 17.7% agreed they feel alone and without friends, while 38.5% strongly disagreed.

Table 1: Parental distress experienced by the parent of special child.

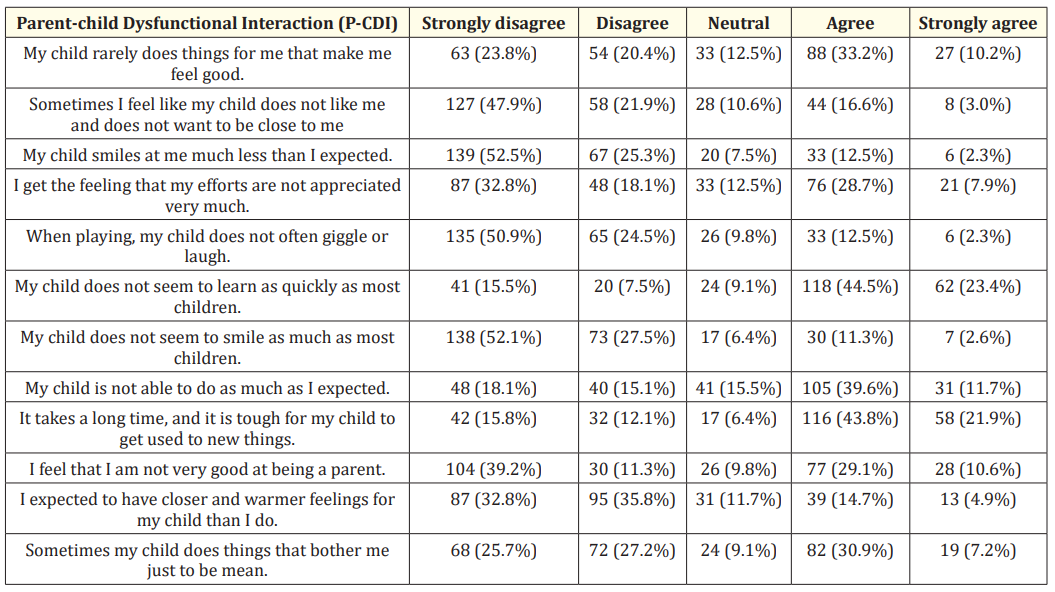

Table 2 records the parental-child dysfunctional interaction (PCDI), supporting the statement mentioned above that most parents were never able to do the things that they like; 47.9% strongly disagreed that they feel that their child does not like them and doesn’t want to be close to them. 43.8% of parents agreed that it takes a long time and it is tough for their child to get used to new things, and 39.6% agreed that their child cannot do as much as they had expected. Moreover, most of the children were unable to learn as quickly as compared to other children; 44.5% of the parents agreed to this. 28.7% agreed that they felt their efforts were not appreciated very much, and 9.8% of the parents thought they were not very good at being parents.

Table 2: Opinion on the parent -child dysfunctional interaction (P-CDI).

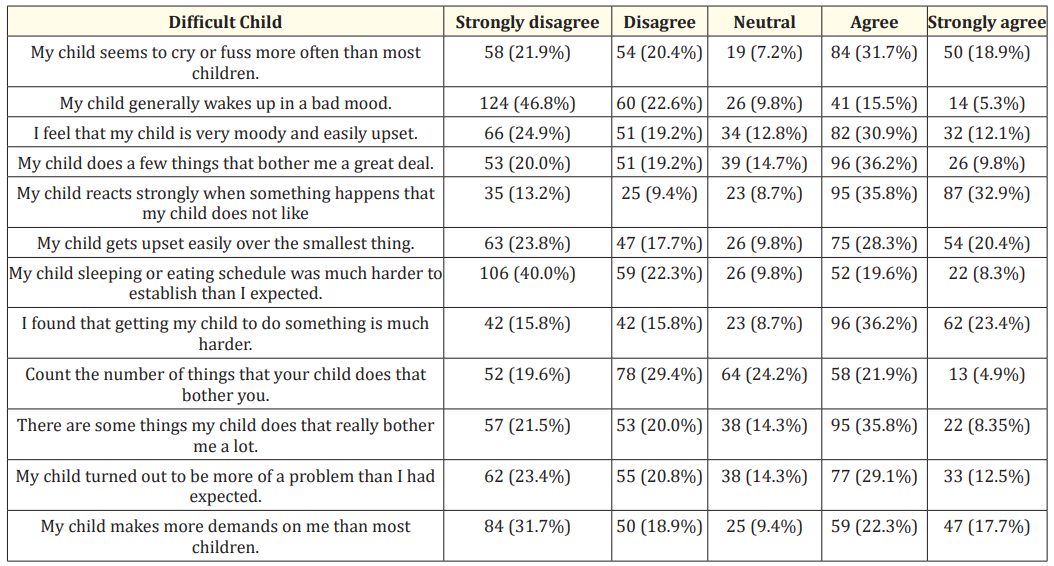

Table 3 records the opinions about the difficult child (DC), our study revealed that 28.3% of the parents agreed that their child gets upset easily over the smallest thing, and adding on to that, 35.8% of them agreed that their child reacts strongly when something happens that he or she does not like. Supporting the above two statements, 31.7% of the parents agreed that their child cries and makes a fuss more than most of the other children. Accordingly, the majority of the parents (36.2%) were really bothered about a few things that their child does, and most of them (29.1%) agreed that their child had turned out to be more of a problem than they had expected.

Table 3: Parents’ opinion on difficult child.

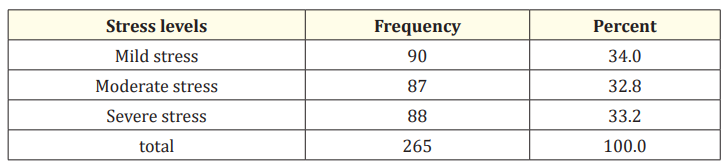

Table 4 shows distribution of the participants based on their stress levels experienced.34% of parents experienced mild stress,32.8% of parents experienced moderate stress and 33.2% of parents experienced high stress levels.

Table 4: Distribution of the parents based on the level of stress.

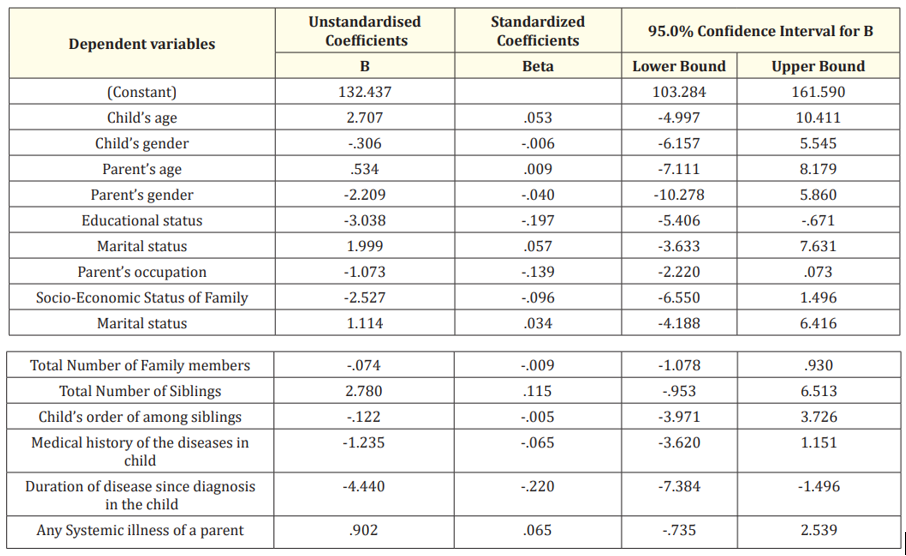

Table 5 shows multiple linear regression analysis with a total distress score, which showed that parents educational status (p = 0.012) and disease duration in the child (p = 0.003*) significantly influenced the total psychological distress experienced by the parents.

Table 5: Multiple linear regression analysis with total psychological distress score as dependent variable.

*P < 0.05.

The birth of a special child is a distressing occurrence that affects the carers emotionally, physically, and socially [6], with parents of disabled children experiencing higher levels of stress [7]. Schmitke and Schlomann in the year 2002 stated that the notion of a perfect child for parents is destroyed when their child has a disability [8].

Most parents experience depression when they think they lack the fortitude to handle the obligations they must take on. This study focuses on psychological distress faced by the parents of special kids using the parental stress index short form.

Most of the parents in our study reported that they were not able to do new and different things and to do so, they had to give up more of their life. This can be because parents do not have enough time for themselves, each other, or their other children since they need to spend more time caring for their impaired child [9], which can lead to them feeling exhausted and tired to try out new things in life. A study by Sawer., et al. in 2011 showed that these parents face both physical and emotional exhaustion, which can weaken them and affect child care [10].

This lack of personal time among parents can cause feelings of loneliness. Supporting this statement, in a review by R. Nowland, G Thomson., et al. reported that parents of a disabled child feel more lonely compared to parents of an average child. This can be due to a sense of helplessness, lack of psychosocial resources and feeling burdened by the child’s needs [11] However, our survey found that contrary to this assumption, the majority of parents do not feel isolated and that they have friends and support groups with whom they can communicate which in turn might affect the level of stress experienced by them.

Most parents felt that they were trapped in the responsibilities as a parent and that they were bothered by quite a few things about their life, which can be because the primary role of taking care of their special child falls on the parents, which can, in turn lead to the parents abstaining from other social activities. Previous studies have indicated that because mothers in households with impaired children shoulder the majority of the childcare duties, they forego other motherly responsibilities and reduce their involvement in social activities [12-16].

In our study, most parents denied to the fact that their child had caused more problems in their relationships. Parental distress and mental health can also be positively affected by the marital relationship as the spouse can be the main support system. Research done by Divya Pillay, Sonya Girdler., et al. [17] have shown that mothers with better mental health had a strong support system from both spouses and immediate family members. A Greek study done by Ntre V., et al., resulted that the mothers of autistic kids have their spouse as the main support [18]. Studies done by Seligman and Darling in1997 have also shown that, when one member of a dyad has high levels of parenting stress, the partner may feel the consequences [19], because partner stress is highly likely to impact the dyad, particularly in families with children who have disabilities. Previous literature by Gavidia-Payne and Stoneman in 1997 and McKinney and Peterson in1987 [20,21] also supports the above statements.

There are numerous more concerns that would perplex parents, such as not understanding how to manage the kids based on the disorder. Parents are frequently held accountable for the behaviour or disorders of their children. Many people are mistakenly viewed as spoiling their kids if they aren’t tough with them or if the kids act out in unusual ways, which can add on to the stress levels faced by these parents.

Additionally, close relatives and friends do not provide parents with adequate assistance in the community, particularly in terms of neighbours and friends. Therefore, it is also demonstrated that having children with special needs affects or disrupts the parent’s social lives due to the time spent caring for and supervising the kids. In a study done on Challenges faced by Malaysian parents in caregiving of a child with disabilities by Bahry., et al. in 2019 reported that some parents might refrain from attending social events because of their children’s upsetting and unmanageable behaviour [22] Contrary to these statements, most Parents in our study denied to the fact that they do no enjoy themselves in a social gathering and also to the fact that they do not enjoy things that they used to do. This may be because parents have adapted to the disability of their child and are likely facing less stress when compared to others. A study done by Mary A Roach and Gael I at the Orsmond University of Wisconsin reported that Parental adaptation may reflect the typical parental reaction to the special care demands associated with raising young children with Down syndrome [23].

In the present study, the parent-child dysfunctional interaction showed that due to the lack of proper communication between the parent and the child, many times, the former may end up being dissatisfied with the extent of the relationship they have with their child. In a study done by Roach MA (1999), fathers who reported more active involvement in the day-to-day care of their young children felt more competent in their parenting roles and reported fewer difficulties in their attachment relationships with their young children than did fathers who reported less active involvement in childcare [23]. But the research results showed that very few parents agreed, and a majority of them disagreed, saying that the child did not like them as much as they’d expected and that they expected to be closer to their child than they already were.

Parents need to understand the limits of their child’s development. When their expectations are not met, parents may have trouble accepting the child’s disability. Lima., et al. (2016) described that some parents have idealised expectations of their children. Failure to meet these expectations may cause difficulty for the parent in accepting the child’s disability [24].

It is also crucial for a parent to be actively involved in the care of their child,which may motivate them to get closer to their child emotionally, which in turn helps them accept the child’s disability and understand the extent of their child’s emotional availability and intellect. A large group of the parents agreed and were worried about their child not learning as quickly as most children and unable to perform or do as much as they’d expected. Many parents also strongly agreed and complained about the child’s delay and difficulty getting used to new things. Supporting our findings, in a study conducted (Pillay D., 2012) among the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome, several mothers expressed their anxiety about the delay in their child’s physical and emotional developmental milestones in comparison to their normally developing peers [17].

Many studies have revealed the importance of moral support and its role in lessening stress in parents of children with intellectual disabilities who have shown better psychological adjustment [6]. Hassal, Rose, and McDonald (2005) have also found a strong association between parent stress and family support [25]. Most of the parents disagreed, while some agreed that no matter how much they put in their efforts, they are not appreciated or supported, which might elevate the stress levels of the already anxious parents.

The condition with which these kids are affected causes them to delay in development and functioning and impairs their adaptability. This makes them more dependent on their parents to do daily routine work like daily hygiene, eating, sleeping, etc [26] and also require extra care and attention from their parents. Parents agreed that getting their child to do something is much harder because it is very difficult to make the child sit in the same place for long and listen to them, and also, they tend to be distracted towards the surroundings a lot.

Research done by Othman, N. W., et al. in 2021 stated that special child experiences difficulties with self-regulation, both physical and temperamental, which makes them very moody and upset over small things, and this supports the feeling of the parents that their child turned out to be a problem to them than they expected [26].

Parents also added that their kids strongly react when something happens that they don’t like. Parents even shared some exceptionally distressing situations in which the child does few things like hurting other children or siblings [17]. Not only this, but also other behaviours of these kids like throwing away the things around them, pushing people away, making different noise, not responding or making eye contact with the parent, and isolating themselves made parents a lot and contributed to stress.

Parents found that their kids cry or fuss more often when compared to the other children. Supporting this, a study done by Roach MA., et al. found that the Down syndrome kids were restless, had a short attention span, and were poor listeners when compared to the typically developing children [23]. Most parents in our study agreed that their children get easily upset over the smallest things because kids are unable to communicate and make others understand how they felt. To see the child suffer in this situation is what causes the parents to worry a lot and get stressed about their kids future.

In a study done by Sen E., et al. 2007, it was found that parents found it much harder to establish the sleeping or eating schedule of the special kid [9]. Another research was done by Mindell JA., et al. In 1991 also proved sleeping difficulties and disturbances are prevalent in children with learning difficulties and cause parenting stress [27]. But Contrary to the above statements, in our study, most of the parents strongly disagreed with it. They mentioned that their kids sleep easily with them as they have a strong intimate relationship with them, and the child feels a sense of safety with them [28].

This study utilized a cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single time. This design limits the ability to determine changes in parental stress over time. Also, this study did not account for potential confounding factors that could influence parental stress, personal mental health issues, coping strategies or access to support services. These factors could have influenced the reported levels of stress among the participants.

Further study has to be done that takes into account not just the experiences of the carers but also those of other family members, who may be impacted by the circumstance, such as the siblings of people with disabilities.

This issue can be resolved by raising social awareness among family members and the general public about various coping mechanisms, such as encouraging parents to join support groups and getting involved in local events. This can help parents who may be feeling lonely get over it and gives them a chance to experience new things.

The results of our study contribute to the understanding that having a special child would not influence the level of stress experienced by the parent. Though the findings were not significant enough, it is crucial to safeguard the psychological or mental wellbeing of such parents through a number of channels, particularly government organizations like the Department of Special Education and the Department of Social Welfare where they should design and implement programs to assist parents by offering services including family counselling, coping mechanisms, and early intervention to maintain a good quality of life.

Copyright: © 2024 Manasa Veena Madala., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.