Mekdes Mihret* and Mulu Fentaw

Institute of Teachers Education and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Educational Planning and Management, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Mekdes Mihret, Institute of Teachers Education and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Educational Planning and Management, Ethiopia.

Received: January 12, 2024; Published: February 22, 2024

Citation: Mekdes Mihret and Mulu Fentaw. “The Status of Women’s Participation in Educational Leadership in Government Secondary Schools: The Case of Dessie Zuria Woreda in South WOLLO Zone”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 7.3 (2024): 25-30.

The main purpose of this study was to assess the status of women participation in educational leadership of government secondary schools in Dessie zuria woreda. Hence, to realize this purpose, secondary school teachers, principals, vice-principals, parent teacher association (PTA) and woeda education officers were used as the target population. In order to make manageable, the sample government secondary schools teachers were selected by simple random sampling technique, and vice-principals, principals, wordea education officers and members of PTA were selected though comprehensive sampling techniques. This study had employed mixed research design particularly concurrent design. Both closed-ended and open-ended questionnaires, semi- structured interviews, and document analyses were used to collect data. The pilot-study was conducted to check the reliability of instruments. Frequency counts, percentages, mean and standard deviations were employed for quantitative data through closed-ended questionnaire and data through qualitative questionnaire were narrated. The finding showed that there is still low participation of women in secondary school leadership and attitude and challenges like misperception of stakeholders, women conflict of roll between their professional duty and family issues, women’s poor self-image remain unchanged. Thus, it was concluded that there is a gap in creating awareness in implementation of policies, rules and regulations in people’s attitude towards women’s secondary schools leadership and competency of female principals is not included in this study. Therefore, it was recommended that the government, the woreda education office society and stakeholders should give great emphasis to work on women leadership; the school leaders should arrange continuous training for school community particularly for female teachers to alleviate the cultural and capacity related factors. The government should seriously look into issues of low women’s participation in educational leadership institutions.

Keywords: Secondary Schools; Educational leadership; Participation; Leadership; Stakeholder; Feminist; Status; Woreda

In Education, leadership is a key element as it enables to inspire change and innovation through mobilization of relatively massive resources in educational organization. It is of particular importance in education because of its far-reaching impacts on the accomplishment of educational programs, goals and objectives. As a result, promoting equality of access to women in the leadership position is a priority subject. Because it contributes to the national development and it helps to promote advancement of women and the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. It is evident that the attention of many countries including Ethiopia is integration of education to development and poverty reduction. To this end, there is also a need to raise the participation of women in the overall development process. This study was attempts to investigate the status of women participation in educational leadership in secondary schools of South Wollo Zone. And this section explores the background of the study, statement of the problem, objectives, scope and significance of the study. It also attempts to state the research design and methods more pertinent to the study, the reliability and validity issues accompanied by ethical research considerations. In doing so, relevant literatures and research outputs were consulted.

In Ethiopia, school administrators has been male dominated; to this consequence the government has set a plan to increase the number of model female students and teachers in school as well as appointing those able women at leadership position [36]. In line with this, some sectors has been seen in increased the proportion of female school leaders such as principals, vice- principals, unit leaders, department heads and clubs heads [36]. Most leadership positions in education and elsewhere are held by men. Leadership in education, as in most fields, is identified with men. Although there is a gradual increase in the numbers of women who are reaching leadership positions, the basic social assumptions, based on the distribution of power in society, endorse men as leaders and identify women in subordinate roles. The presence of women in leadership position in education provides a gendered perspective on educational change and department to insure social justice through gender equality at leadership and decision making levels. The presence of women in leadership roles at secondary school level and above provides to sensitivity within schools for the wellbeing of adolescent girls and provides girls beginning to consider carrier choices with role models of decision makers and leaders [45].

Sperandio (2006) [45]. also explained that more educated a person is it would be legible for acquiring leadership position. As women are educated, they would be capable of making decision, influencing other create, ideas and managing situations. While this lies true, traditionally management has been dominated by men. Women are having a trouble breaking in to senior level management. Promoting women’s access to leadership positions is particularly significant in the education system, because, not only that it helps to enhance gender equality in the education sector; but it also creates female leaders who can be role models to thousands of school girls. The argument for women’s participation in decision making and leadership is based on the recognition that every human being has the right to participate in decisions that define her or his life. This right is the foundation of the ideal of equal participation in decision-making among women and men. It argues that since women know their situation best, they should participate equally with men to have their perspective effectively incorporated at all levels of decision-making, from the private to the public spheres of their lives, from the local to the global [34].

Moreover, the Ethiopian government has been committed itself to various national, regional, and international initiatives to eliminate gender-based disparity in various sectors by introducing various policy directions and institutionalizing ministerial offices. To cite few examples, the establishment of the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, its commitment on Millennium Development Goals (2015), Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP) the Gender Mainstreaming Guidelines, and the various affirmative actions taken in education and employment process. One of the major goals of the MDG also focuses on gender equality with the target of eliminating gender disparity in education, employment, and political participation by [46]. However, regardless of the Ethiopian government’s policy of equal opportunity for both men and women to participate in the democratization of the country, women have not been adequately represented at all levels of decision-making positions. Given the nominally equal status of men and women in laws of most countries, it is only right that both sexes participate in decision making over matters that affect them.

Furthermore, mentioned barriers to gender inequity are unseen gender inequities, male dominance, stereotyping intertwined with barriers of sexism, bias, and discrimination against potential and current females in educational leadership, role conflicts, low salaries, and high job demands, family obligations, and lack of confidence, aspirations, and risk-taking [42]. Within educational leadership [26] also mentioned that women are still under-represented and thus under-utilized [52]. Again indicated that in recent years, ambivalence, resistance and antipathy have redeveloped around gender issues, making it more difficult for feminist scholars to continue to work for gender equity in the leadership field in the United States. In the same vein, in educational setting while women hold the teaching staff position, men dominates the highest position of educational leadership [36]. Therefore, it is to be high lightened that due to low educational attainment, societal stereotypes institution barflies that hampers the upward movement of women within organizations. One could hardly find women holding a management and decision making positions. This would retain many women from facing the challenge and exercise decision making role [31].

According to the 2014 Annual report of Dessie zuria [11] woreda government education bureau, women were not involved in the educational leadership position, and 100% of men are employed in leadership position in all secondary schools of Dessie zuria woreda. This indicates that the total number of women participation in educational leadership is too less relatively from male’s involvement. Due to the various obstacles that women have such as triple role, violence against women, training, lack of self-confidence, low motivation, lack of education etc., their representation and participation in leadership and decision making position has also been limited. Thus, the genesis of this paper intends to assess the status of women participation in leadership public secondary education in Amhara region in Dessie zuria woreda by used mixed research design.

Women from the core of the family and household work longer hours than man in nearly every country and do more of the total work than men, and women contribute more of the development of their societies [31]. Women’s low status in Ethiopia, as anywhere else, is expressed in different forms including in their lack of assets to ownership, leadership and decision making opportunities and their multiple role that made them lag behind endeavor. Moreover, it is believed that women are reluctant to accept responsibilities of school leadership; men are better leaders in leading secondary school; the school manager should be masculine, self-reliant, ambitious and strong leader; women have no necessary skill to discipline student, supervise other adults and criticize constructively in secondary school; men consider women as his equal counterpart and women lack confidence in their capabilities, qualifications and experiences. Some of the challenges which could hinder women representation in educational leadership were for instance; pressure of home responsibilities, men dominance of management position, political appointment, unclear promotion procedures or informal recruitment selection and training, discrimination in religion and organization, etc [41].

Currently, there is a better opportunity for women to participate in school leadership; education has been given priority all over Ethiopia. Many government secondary schools have been established and women’s participation in teaching is increasing. But still the school stakeholders believe that women are reluctant in accepting responsibilities of school leadership, men are better leaders in leading secondary schools, and the school managers should be masculine, self-reliant, ambitious and strong leaders.

Moreover, women’s leadership participation in Ethiopia has been a deep rooted problem, unless the necessary measures are taken. I observed insignificant number of women leaders in Dessie zuria woreda government education bureau. This problem has attracted the attention of government, nongovernmental organizations (N.G.Os), international educational organizations (UNESCO, UNICEF) [48] to identify the causes of the problem and find means of alleviating it and capacitate or empower women to participate in the educational leadership career. All the factors estimated to be hindrance to women’s educational leadership participation must be researched and deeply investigated to obtain active and effective women’s educational leadership participation.

However, the government policy towards women’s participation in leadership has been given more emphasis; there is an indication that some challenges towards women’s participation are not totally eliminated. Though several studies were conducted in many parts of the country (Ethiopia) related to barriers, and factors that affect women participation in educational leadership, but none of these studies attempted to examine its status or level on secondary schools women participation in educational leadership.

Therefore, the researcher believes that this study would help fill in the gaps observed in other studies as it mainly revolves on investigation to assess the status of women participation in educational leadership of government secondary schools in the identified study areas. To attain the intended objective, the researcher has forwarded the following research questions.

The study has both general and specific objectives. The general objective of this study was to assess the status of women participation in educational leadership of government secondary schools in the identified study areas.

By assessing the status of women participation in educational leadership in secondary schools the study is intended to bring about the following substance

Delimitation of this study was included both geographical and conceptual area. Regarding geographically, the study was delimited to encompass sample government secondary schools found in South Wollo Zone Dessie zuriy woreda. Besides, conceptually, the study was delimited to study policy contribution, attitudinal change and challenges so as to indicate the status of women participation and attitudinal change of the society. The study also delimited towards women participation in secondary school principal ship because the previous trend showed no women were exercising in the principal ship/leadership position in selected secondary schools. So that it may help to know the changes and still to investigate the challenges.

The researcher had faced some problems such as unwillingness of some respondents in filling the questionnaires and return on time; filling the questionnaires carelessly without reading and understanding the issue. The selected school principals and vice principals were busy and had no enough time for interview; teachers, PTA and WEO were to respond questionnaire.

The researcher managed and tried to minimize the above problems or factors with the help of some friends and the return rate of the questionnaires also maximized, particularly some principals helped the researcher by encouraging respondents to fill in the questionnaires and return it. The researcher used formal and informal communications to obtain the required data of the study.

This study was organized into five sections. The first section deals with the background of the study, statement of the problem, objectives of the study, significance of the study, delimitation of the study, limitations of the study, definition of the key terms and organization of the study. The second section covers review of related literature. Section three deals with the research design and methodology, section four covers the analysis and interpretation of data collected. Lastly, section five of the study deals with the summary of the major findings, conclusions and recommendations. At the end, references and appendices are attached.

This chapter presents some important topics, which are related to factors affecting Women’s participation in Educational Leadership. Books, journals and other material sources were used to review the topic. The major topics discussed include: overview of leadership, women and educational leadership and barriers that prevent women’s participation in educational leadership. The strategies and actions that promote their participation in educational leadership are also presented in this chapter.

Although many definition of leadership exist, (Hughes., et al; 1999) defines leadership as the process of influencing others towards achieving group goals. They describe leadership is both a science and an art. Because leadership is an immature science, researchers are still struggling to find out what the important questions in leadership are; we are far from finding conclusive answers to them. Even those individuals with extensive knowledge of leadership research may be poor leaders; knowing what to do is not the same as knowing what to do is not the same as knowing when, where, and how to do. The art of leadership concerns the skill of understanding leadership situations and influencing others to accomplish group goals.

Hersey [20] as the management writers define that leadership is the process of influencing the activities of an individual or group in efforts toward goal achievements in given situation. From this definition of leadership, it follows that the leadership process is function of the leader, the follower and other situational variables.

[25] define leadership as the process through which leaders exert such influences on other group members. Throughout your life you will lead others land be led by others, providing leadership and following someone else’s leadership pervade all aspects of life, including work, school, play and citizenship. Whatever the actions taken, leadership involves social influence.

Instructional leadership definition According to [22] “instructional leadership is a particular form of leadership that emphasizes the improvement of teaching and learning in school’s technical core”. “an instructional leader has a sense of purpose and a broad knowledge of the educational process and learning theories she’s a risk taker, and has people skills and unlimited energy” [33].

Principle centered leadership is the personal empowerment that creates empowerment in the organization. It’s focusing in our circle of influence. It’s blaming or accusing; it’s acting with integrity to create the environment in which we and others can develop character and competence and synergy [10]. Effective leaders need to develop appreciation for multiculturalism to build inclusiveness, collaboration, and common purpose.

Line managers take full responsibility for recruitment and selections although personal specialists, if they exist, may provide such services as advertising, filtering applications, testing and taking up reference, are responsible for training and developing their own staff on a self-managed learning basis, accountable for dealing fairly with their staff and meeting goal requirements in this areas as equal opportunity, sexual, racial and disability discrimination, and sexual harassment, are fully responsible for controlling absenteeism and time keeping [21].

Leaders are important because they serve as anchors, provide guideline in times of change, and are responsible for effectiveness of the organization [23].

According to Armstrong, leaders have two important roles. These are [1] achieve the task that is why their group exists. Leaders ensure the group’s purpose is fulfilled. It is not, the result is frustration, disharmony, and criticism and eventually perhaps, disintegration of the group [2] maintains effective relationships-between themselves and the members of the group, and between the people within the group. These relationships are effective if they contribute to achieve the task [21].

As a line manager one of your key tasks is to ensure that you have the right people to do work. You have to replace those who leave, are promoted or are transferred with people who are just as good, if not better. You have to find people who meet your specification for new roles [21].

In one sense, your roles as a line manager or team leader involves your continuously in the management of learning and development. New starters have to receive induction training to enable them to carry out their work. They will then need to learn new skills or increase and extend existing skills; as develop and are given new tasks, learning and development takes place at the following stages and in the various ways as set: induction training, learning on job, learning off job, [21].

[54] points out that it has become clearer that effective leadership at all levels of society and in all our organization is essential for coping with the growing social and economic problems confronting the world. Coping with these problems better is not a luxury but a necessity. Effective Leadership, according to Principled-Centered Leadership sums it up as, “Give a man a fish, and you can feed him for a day, teach him how to fish, and you can feed him for a lifetime” [9]. Furthermore, Fiedler [14] defines leadership effectiveness as “the extent to which the group accomplishes its primary task”. He goes on to say that although the group’s output is not entirely a function of the leader’s skills, the leader’s effectiveness is judged on how well the group achieves its task [32], states that in all cases, leader effectiveness is determined by the degree to which the task is or judged to be achieved. For example, if the academic performance of a Secondary School is high in external exan1ination, then this shows the degree of leader effectiveness. In today’s world, in order to be successful and become an effective leader, Klan (2004) underlined three important things that leaders must perform simultaneously. They are to achieve the desired results, develop and care for their employees as well as conduct themselves in an ethical manner i.e. community, social and environmental consciousness. Furthermore, Larson and La Fasto (1989) maintained that “effective leaders give team members the self-confidence to act, to take charge of their responsibilities and made changes occur rather than merely perform assigned tasks”. In short, they concluded, “Leaders create leaders”. In schools, Baltzell and Dentler (1983) [1] stressed that outstanding schools have outstanding principals and what characteristics make a principal or in-school administrator outstanding, effective and efficient are open to discussion; however, good principals appear to require highly professional and personal skills.

It is the process of enlisting and guiding the talents and energies of teachers, pupils and parents towards achieving common educational aims. This term is often used synonymously with educational leadership in the United States and has supplanted educational management in the United Kingdom. Several universities in the United States offer graduate degrees in educational leadership.

The term educational leadership came to currency in the late 20th century for several reasons. Demands were made on schools for higher levels of pupil achievements and schools were expected to improve and reform. These expectations were accompanied by calls for accountability at the school level.

The term “educational leadership” is also used to describe programs beyond schools. Leaders in community colleges, proprietary colleges, community-based programs, and universities are also educational leaders. (www.en.wikipedia.org).

Leadership is of particular importance in educational administration because of its far- reaching efforts on the accomplishments of school programs, objectives and the attainment of educational goals [32]. Furthermore, [40] emphasize that the examining of the leadership phenomena of educational organization and administration is “with concepts and theories of leadership that are applicable to those who hold decision making positions such as principals, school inspectors, department heads in the various hierarchies of the educational organizations.” [50] defined Educational Leadership as.

“The process in a school which yields control of pupils, teachers, parents, administrators and others upon principles which should govern administration, operation and management of schools, which yields agreement among these same group concerning policies, which should be adopted by the school member and brings about plan of action for dealing with school problems. “

Educational Leadership is essential to change, to indicate and involve in activities, which lead to change and innovation. In addition to this, [29] pointed out that, “Educational Leadership is pivotal for the accomplishment of some highly important issues in the school setting.” The prime motive of the educational leader is achieving a high level of student progress in knowledge and skill, which is the ultimate goal of a school and that of a community in general.

Leadership was thought of wholly in terms of the head teacher or principal. This is not so nowadays, with the prevailing view that leadership is a permeable process that is widely distributed throughout educational institutions. It is also known as the empowering process enabling others in school to exercise leadership [6].

They further noted that the rationale behind it is that, in order for any high performing organizations or institutions to attain their objectives and goals, all sections and departments within the organization should be ‘full on’ and eradicate any underperformance or slack within the job itself. Leadership is therefore seen as a distributed concept where it is seen as ‘an influence process’ and a ‘set of tasks connected to a particular position.’ In reality, incumbents of different positions also need to apply the influence processes to particular spheres of responsibilities, and those are often, and likely to be different.

Educational leadership refer to leadership influence through the generation and dissemination of educational knowledge and instructional information, development of teaching programs, and supervision of teaching performance [44]. It is relevant in all educational institutions right from preliminary schools to universities.

Education is an industry that involves various stakeholders (students, teachers, administrative personnel, parents, political authorities as well as the general community) on educational decisions. Education is believed to play a pivotal role in any economy in relation to overall socio-economic development of any country. Owing to this, educational institutions demand better quality leadership. In this regard, the peculiar natures of the educational institutions (crucially, complexity, visibility and the like) elevate the real call for strong, innovative and transformational leaders who have the talent and courage towards creativity. In view of this, both developed and developing countries have started to provide due attention to the importance of educational leadership.

In Education, leadership is a key element as it enables to inspire change and innovation through mobilization of relatively massive resources in educational organization. It is of particular importance in education because of its far-reaching impacts on the accomplishment of educational programs, goals and objectives.

An efficient educational leader has to stay updated with the changes in the field of education. Generally, educational leadership involves leading departments, decision making committees, educational facilities, monitoring performance of teaching staff, assigning them work.

Leadership in education as in most fields is identified with men giving subordinate roles to women. That trend is also apparent in the field of education and there is something paradoxical about it. Even though, teaching has traditionally been seen as a “suitable” job for women, a large numbers of women in the profession and greatly underrepresented in positions of management [8,10]. Keeping this paradoxical situation in mind, this section reviews a number of issues including leadership role of women in educational sector, women and leadership styles, women’s leadership abilities, skill and competencies, women’s aspiration to educational leadership, current requirement and selection criteria used for selecting educational leaders.

It is said that women hold up half the sky, implying that at least s50%of the world population are women. Women form the core of the family and household, women work longer hours than men in nearly every country and do more of the total work than men, and women contribute more to the development of their societies [31]. Thought this is so occupational segregation to inter the labor force based on gender is still evident in many countries. This can be due to two major factors, according to [27], formal and informal barriers.

People are both the ends and means of development. The wsomen and men are the main actors, and each constitutes half of the population in the world. Therefore the development has to succeed the untapped potential of women has to be utilized in the process (Aynalem, 2003). Women play a crucial role in food security and food production in most developing countries. They are responsible for half of the world’s food production. Similarly, women are the health agents of the household and they have a key role in household maintenance, family nutrition and education. However the ability to produce enough food and earn adequate income which would insure food security is hindered by unequal resource allocation that is access to input, credit, extension service, and access to technology (Ibid).

Similarly [16], describes that gender-biased planning and unequal resource allocation have left women little room, if any, to increase their role in production; in this regard, development activities have to be geared towards increasing the capabilities of both men and women thereby to satisfy their basic needs and aspirations as a basis for a healthy society. Because of gender biassed planning women have not benefited for the development process. They have limited access to productive resources, higher education and training, and they have little educational opportunities. The majority of women earn their meager incomes from the informal sector. The informal sector doesn’t offer adequate job opportunities to all women and those who are already engaged in this sector have little income for survival. In many of the developing countries, women are over-represented among the poor, with in adequate basic abilities and facilities. The number of female- headed households shouldering family responsibilities is increasing rapidly.

In relation to human rights all over the world, women are denied their rights. Gender differentiations are about inequality about relations between women and men. Half of the world’s people are subordinate to other half, in so many different ways because of the sex they are born with. Despite international human rights law which guarantees all people equal rights, irrespective of sex, race, caste and so on, women are denied equal right rights with men to land, to property, to education, to implement opportunities, to shelter, to food, to worship and over the lives of their children.

Based on less participation of women in leadership many authors wrote different ideas.

Augsburger (1992) states that possess many powers, but they are limited, channeled, suppressed, and denied by men’s power. The more valuable, crucial or brilliant the gifts of woman, the more males and male dominated structures are willing to exploit them or the credit for them. The author maintains that, the man who dominate the judicial system in Egypt have been able to prevent women from becoming judges on the assumption that a women, by her very nature, is unfit to shoulder responsibilities related to a court law. This assumption built on the fact that Islam considers the testimony of one man equivalent to that of two women. The argument, therefore, is that testimony only consists in witnessing to something that has not happened, and if a women cannot be trusted to the same degree as men on such matters, how can she consider the equality of man when required to give a decision on a point over which two parties are disagreement. Although women maybe appointed as a minister in Egyptian government with administration over thousands of male and female employee, she is not allowed to mediate disputes even as a pretty court judge or become a head of village who will mediate quarrels and conflicts. Male power is used to limit, channel, suppress, or deny women’s powers (Ibid).

Similarly Ruth (1998) argues that the proportion of women in top administrative jobs in America is quite low, but women may be encouraged to pursue the traditional “female” specialties such as pediatrics, psychiatry, and preventive medicine. More than 95% of senior strangers at major industrial and fortune 500 companies are male. And the proportion of women that work in televisions as prime-time producers, directors and writers ranges from 8- 26% on the networks. He wrote that, for most of our history, women have been notably absent from sciences and engineering. The proportion of engineers is who are women has increased considerably in recent decades- from less than one to more than eight percent. Nevertheless, even when they have the same education, time on the job, and occupational attitudes, women are less likely than men to achieve high-status position or to move in to management. And they have been used to justify the fact that women historically have had fewer educational opportunities as lower paying jobs. But the right to equal economic opportunities only begins at the point of gaining employment. However, there is discrimination both in hiring and in promotions, including discrimination in the sense that women are often discouraged from entering certain occupation. In any occupational categories, women are found disproportionately in the lower jobs.

Hughes (1999) asserts that, both male and female managers in fortune 100 company were interviewed and completed surveys about how they influence upward how they influence their own bosses. The result generally supported the idea that female managers‟ influence attempts showed greater concern for others, while male managers‟ influence attempts showed greater concern for it. Female managers were more likely to act with the organization’s broad interest in mind. Consider how others felt about the influence attempt involve others in planning, and focus on both the task and interpersonal aspects of the situation. Male managers, on the other hand, were more likely to act out of self-interest, show less consideration for how others might feel about the influence attempt, work alone in developing their strategy, and focus primarily on the task alone even though, the participation of women in higher position is low.

Aynalem (2003) concludes that the aspect of equality which takes the form of women’s equal participation in the decisionmaking process. In a development project it would mean women being represented in the process of needs assessment, problem identification in the community at large. Equality of participation is not easily obtained in a patriarchal society, so that women’s increased mobilization will be needed to push for increased presentation. Women’s increased representation is potential contribution towards their increased empowerment.

Over the past decades, Women in Leadership have been viewed as anomalies, as deficient, with respect to the traditional male models of leadership [19] has described female Leadership as web-like, dynamic, continuously expanding and contracting. He claims that it is highly connective, deriving its strength from empowering others. Therefore, female leadership then takes on different appearances, different shapes, and different directions as a web in constant redesign. The term ‘Women Leaders’ embraces a heterogeneous rather that a homogeneous group. It is composed not only of women who have risen to senior positions and held these posts for many years, but also swomen who have risen from fairly subordinate positions to obtain a post of some responsibility, but will never make it to the top, plus the new generation of young graduate high flyers who have set their sights upon the most senior jobs. There is also a further group known as ‘aspiring or potential’ women managers who have not yet achieved a position of responsibility but would like to do so [7]. In the past, the subject of leadership in women has been confined to anecdotal figures that are remarkable for their small numbers. It is readily apparent, when we examine the education job market as a whole that the rate of participation of women diminishes the higher up the occupational hierarchy we move. Proportionately, fewer women stand on the top rungs on the managerial ladder than on the bottom.

Meanwhile, for Amalia Vanoli, (2014) Director of the human resources consulting firm Tiempo Real, women executives have higher emotional intelligence; they create good work teams where they motivate without losing sight of the results. “Today some organizations prefer women for certain positions. In general these are companies that have experienced the benefits of female leadership and have strong internal policies in support of gender diversity,” she adds.

Female leadership is necessary in teams, organizations and in society: with this, all benefit. That is why we need leaders from both genders to complement each other.

Organizations today are more flat and interconnected since changes occur faster than before. This is why “we look for characteristics like collaboration, empathy, sensibility and consensus that relate more to the feminine side. In general women tend to participate more in finding the best solutions within a work team,” says Rama (2014).

According to researchers, when women assume a leadership role they experiment changes in their behavior: some of their unique features are intensified; features that had previously not been part of their character appear stronger; they have a faster discerning capacity and precision in making decisions. The thing is that when women are given the opportunity to lead or to become the head of a team, they take it as a true challenge and fully focus on the project that is taking place.

Some of the barriers those keep women from becoming leaders are as follows.

Women who aspire to become leadership are more likely to response lowered aspiration than men (3). In studies of female, aspiring to become administrators, (4) found a marked lack of selfconfidence.

In their finding related to aspiring leaders (49) indicated that women lack of sense of themselves as leaders and perceive that they have further to go in developing this leadership identify than to men.

Family and home responsibilities, place bound circumstances, moves with spouses or misalignment of personal and organizational goals were early contributors to women’s lack of leadership success, either because the demands of family on women aspirants restricted them or because these who hired believed that women would be hindered by family commitment (Hewitt, 1989).

According to [43], a direct impediment for females in attaining leadership positions is the reality based factor of family responsibility; continued to voice this concern some years later from data obtaining in 1993 by Kamler [43].

The component of administrative work, as well as the perceived and real male- defined environments in which many women administrators must work, shape women’s perception of the desirability of administration. Schmuck A. (1986). Determined that women’s failure to aspire to the leadership might be a result of their experiences working with male leaders, role models whose leadership behavior may not be compatible with women’s preferred ways of leading.

[43] noted research studies from the late 1970s (Roughman, 1997) that pointed out that women traditionally had little support, encouragement, or counseling from family, peers, superordinate or educational institutions to pursue careers in leadership position. Empowerment has continued to be an important factor for women moving into position [17]. Found that lack of empowerment was one of the reasons female’s elementary school teachers in Kanasas reported not entering administration.

Traditional stereotypes cost women and minorities a socially incongruent as leaders, they face great challenges becoming integrated into the organization [5].

The 1985 Hand book for achieving sex equality through Education reported socialization and sex role stereotyping have been potent obstacles to increasing women’s participation in leadership position” [43]. Since the mid-1980, studies have continued to report that women believe that negative stereotypical and inaccurate views held by gatekeepers about women are their perceived inability to discipline workers, supervises of other works, criticize constructively manage finances and function in political frame [5,43] Supported these finding, pointing out the existence of the myth that “women are too emotional and can’t see things rationally and so that affects their decision making”

According to Singh (2002), the underlying premises of this perspective is that women and men are equal capable and committed assuming positions of leadership, but the psroblems versed in the structure, among the structural factors are (Ibid): • Discriminatory appointment and promotion policy

Despite some progresses institutional barriers are still contributing to women’s invisibility from top leadership position (Ibid).

Education is a critical element to increases the upward socioeconomic mobility of women and creates an opportunity to other hand, as educational background of women becomes less. The activities they perform tend to be less- valued, and their low status is also perpetuated through the low value placed on their activity [30].

The fact that illiteracy rates are nearly always higher among women than men and it is a major limiting factor in women’s contribution of development. The failed to eradicate and train female equally with male limits women’s roles and makes them inadequately trained for employment opportunist that may available.

Therefore, having the right qualifications and training are central as policies and practices in the work place helps to eradicate discrimination at all levels (Ibid).

The current under-representation of women in top leadership positions is reflected in several research studies conducted on women in educational administration, which reveal many critical problems facing women when they try to enter or advance in administrative careers [43,47]. In spite of these difficulties regarding entry into leadership in education, the continuing discrimination in hiring and promotion, and other external and internal barriers, these women persistently pursue roles in leadership [13].

Leadership development as a process is assuming even greater importance of the growing complexity of education and worth its increased tendency towards specialization, there is greater need for women leaders to have coping strategies as well as develop actions to be taken in order to overcome barriers women face in the participation of educational leadership. In this regard, Albino (1992) suggests that female leaders must learn to develop and use work strategies to help them cope and achieve success in leadership positions.

Administratively, one of the reasons for women’s under representativeness in the leadership positions is that many educational organizations are hierarchically structured with the majority of women visible at the base of the pyramid and a very negligible number visible at the apex. In order to reverse and increase women’s participation, organizations have to take a good usage of appropriate selection and promotion criteria (Ruderman and Ohlott, 2002). They further stressed that these decisions are influenced by the visibility of various candidates, where the visibility leads to greater opportunity, which in turn leads to rewards.

Wellington and Catalyst (51) also agree that visibility is very important for advancement and leads to advancement. Women need to showcase their talent and accomplishment that people with power to make decisions, know about them and think of them for opportunities; however, women can be vulnerable and be subject to jealously causing a serious loss of support from colleagues. Therefore, women need to set up a strategy for advancement that requires technique and savvy. Organizations need to address the climate of gender equity that refers to the extent to which an organization values both masculine and feminine norms. By [36]. doing so, it results in enhanced organizational performance by creating a safe environment at the work group level, making it a place where employees can discuss challenges in balancing life’s different domains, strengthen women’s feelings of connection by creating, developing both formal and informal networks, take a good look at women’s performance evaluation systems as well as usage of appropriate selection and promotion criteria and norms of work groups and interpersonal relationships need to change to create a performance culture inclusive of women (Ruderman and Ohlott, 2002). [7] claimed that if women are to be given careers which make unusual demands on their time and energy and which at some point may conflict with their personal life, then it seems sensible for an organization to continue its investment in this person by encouraging to stay, with the offer of extended maternity leave. Women especially need help when they have babies. “The government won’t help them, so companies must”. Institutions need to reexamine their organizational culture and work practices so as to create a more women-family-friendly institution. This meant issues like introducing flexible time, career structure for promoting workers and parental leave and emergency leave for caregivers.

Women appointed to leadership positions are more than just professional employees. Very often, these women are also mothers, wives and housekeepers. Each of these roles, if done well require full time effort. The demanding pace of their days and the contemporary pattern they face requires women to develop personal skills and learn strategies to help cope and access success in their leadership positions.

The contemporary world is male dominated in which genderpower relations are clearly adjusted in favor of men. The prevailing internationalized patriarchal system excluded women from every sphere of public life including leadership and decision making structures [21].

In Ethiopian women have demonstrated considerable leadership in community and informal organizations, as well as in public office; however, socialization and negative stereotyping of women have reinforced the tendency for leadership and decision-making to remain the domain of men. In Ethiopia, there are many sayings (proverbs) that reflect the inability of females to play leadership roles or to exercise other decision-making situations.

One of the areas of disparity between male and female is related to the difference in their employment status which is manifested by occupational segregation, gender based wage gabs, and women’s disproportionate representation in informal employment, un paid work and higher unemployment rates (UNFPA,2005:14). This disparity shows that as women have low states in the community, the activities that they perform tend to be less valued and women’s low status is also perpetuated through the low value placed on their activities [30]. The problem of gender- inequalities discussed above is very much prevalent in, and relevant to Ethiopia. Ethiopia is a patriarchal society that keeps women in a subordinate position. There is a belief that women are docile, submissive patient, and tolerant of monotonous work and violence, for which culture is used as a justification [21].

In spite of that, women are severely underrepresented in leadership position at all levels in the education sector in all regions in Ethiopia [35].

Women’s low status in Ethiopia, as anywhere else, is expressed in different forms including in their lack of assets to ownership, leadership and decision making opportunities and their multiple role that made them lag behind every endeavor. Only 30.8% of female employments are in the formal sector, which are mainly engaged in clerical and fiscal administrative positions earning less than 200.00 birr per month. Moreover, only 29% of professional positions are occupied by women compared to 71% that of men. Moreover, illiteracy is high at74%, 54% for male and 75% for female. The gap goes wider as one goes higher the educational ladder [37].

Furthermore, numerous and varied customs and traditions prevalent in the country continue to define ‘ women’s appropriate public behaviors’ trigger interlocking forms of institutional exclusion of women. Besides, the decision-making environment is not gender friendly. The situation is further exacerbated in a country where the political and culture background does not encourage women’s participation. These among others have made women’s participation in various development endeavors mainly in leadership and decision making positions insignificant, where most important decisions that affect their life are taken.

The socialization process which determines gender roles is partly responsible for the subjugation of women in the country. Ethiopian society is socialized in such a way that girls are held inferior to boys in the process of upbringing, boys are expected to learn and become self-reliant, and responsible in different activities, while girls are brought up to conform, be obedient and dependent, and socialized indoor activities like cooking, washing clothes, fetching water, caring for children etc [18,21].

The low participation of females in education affects developing countries not only from fully benefiting from role females play in development, but also from attaining international and national declarations and goals of education. To address this problem, many countries including Ethiopia formulated legislations that address specially equity issues. The main policy response is the declaration of Universal Primary Education. In MOE (1999), it was stated that apart from ascribing in 1964 to the universal declaration of right which declares that everyone is entitled to the basic rights of literacy, Ethiopia in 1990 participated in the worlds conference on “Education For All” and along with other signatories pledged to devote renewed efforts to providing education for all with particular attention to promote the participation of females in education. The policy presents that by providing administrative, financial and material support, the Ethiopian education will promote the participation of women in education and education will be an instrument to aware societies and change their attitude about the role of women in development [36].

The government has also established the Women’s Affairs department in MOE and some regions have also formulated the Women’s Affairs department and units to address gender issues in education, to create awareness and initiate attitudinal change. In addition, a number of awareness creation programs, training at different levels were conducted by MOE, government and nongovernment organizations. Many researches were also conducted to identify the problems that hinder the participation of females in education. Due attention was also given to promote the participation of Women in Educational Administration as stated in Article 3.83, “Educational Management will be democratic, professional, co-coordinated, efficient and effective and will encourage the participation of women” [39]; however, in the above directive, due consideration was not given to females participation. Attention was only given to their performance, service years and experience etc. To promote or advance the participation of females, it is necessary to give them due attention during selection, setting special quotas in the directives and facilitating other strategies.

This chapter presents the procedures that were used to conduct the study, focusing on research design, target population, sample and sampling techniques, research instruments and finally methods of data analysis.

In this study, mixed research design particularly the concurrent mixed design was employed. Mixed research design is an approach to inquiry that combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches (Creswell, 2009). It is more than simply collecting and analyzing both kinds of data; it also involves the use of both approaches at the same time, so that the overall strength of the study greater than either quantitative or qualitative research. It is practical in the sense that the researcher is free to use all methods possible to address a research problem (Creswell and Miller, 2002). Therefore, the main reason to use the concurrent mixed method procedures is in order to converge or combine both the quantitative and qualitative data to provide comprehensive analysis of the research problems. This method particularly concurrent mixed method is more convenient to get in-depth data on this study. In this method the data may be collected at the same time and integrates the information in the interpretation of the overall results. Also, in this design the researchers may embed one smaller of data within another larger data collection to analyze different types of questions (Creswell, 2009). Thus, mixed research design was appropriate to gather data on the status of women participation in educational leadership in government secondary school of Dessie zuria woreda in South Wollo Zone.

The researcher applied two types of source of data. They were primary and secondary sources of data. The primary sources of data were school principals, teachers, deputy/vice- principals, PTA and people from woreda education offices working in Dessie zuria woreda secondary schools. Besides, secondary source of data were obtained documents, records of strategies to assign principals and annual statistical reports from Dessie zuria woreda.

In Dessie zuria woreda there are 4 general secondary schools. All these government secondary schools are target population of the study.

The samples of the study are secondary school principals, teachers, woreda education office, deputy principals and PTA. The researcher believes that they are the right source of information for studying, the status of women participation in educational leadership in government secondary school of Dessie zuria woreda in South Wollo Zone.

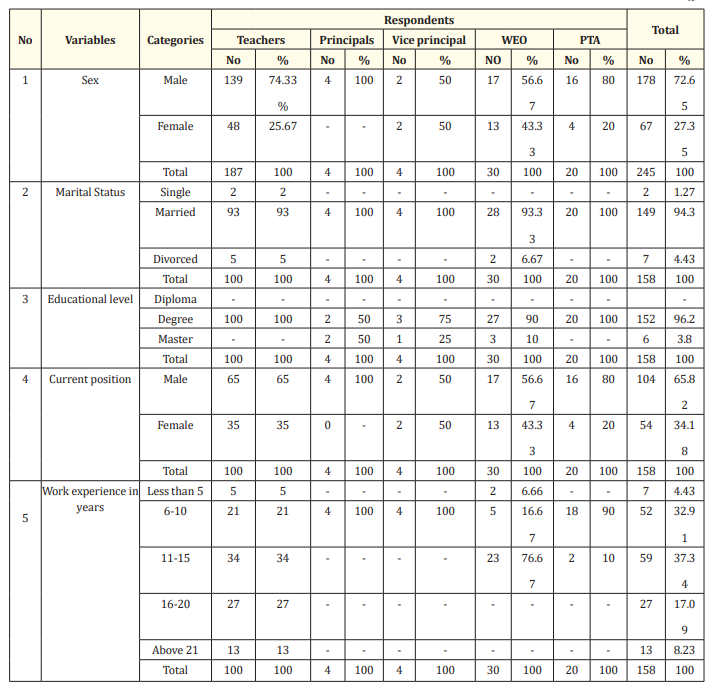

As mentioned above, there were 4 governments secondary schools were selected a sample by using comprehensive. And also principals and vice principals, PTA members and woerda education offices were selected by using comprehensive sampling techniques. Teachers were selected a sample by using simple random sampling techniques using lottery method. According to Leedy and Ormrod (2005) in simple random sampling technique, each member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. Fortunately, the 4 selected secondary schools were Ayalew Tessema general secondary school, Hedasie general secondary school, Gelsha general secondary school and Berar Gatera general secondary schools. As a result, the following table depicts the population, sample size and sampling techniques of the study.

Totally, the researcher selected 100 teachers, 20 PTA members, 8 both principals and vice- principals, 30 woreda educational offices from the 4 schools. Totally, the number of respondents for questionnaires was 150 and in addition, 4 school principals and 4 vice principals were selected for interview purpose.

The study employs two major instruments in data collection. These were questionnaires and interview. Denscombe (1998) asserts that there is no single research technique that is adequate in itself in collecting valid and reliable data of particular research problem.

The questionnaire is a form prepared and distributed to secure responses to certain questions. It is a systematic compilation of questions. It is an important instrument being used to gather information from widely scattered sources. Normally used where one cannot see personally all of the people from whom he desires responses or where there is no particular reason to see them personally.

![Table 1: Population, Samples and Sampling Techniques. <br>

Source: Dessie Zuria woreda education office, (2014) [11].](https://actascientific.com/ASPE/images/IJMCR/ASPE-07-0653-table1.PNG)

Table 1: Population, Samples and Sampling Techniques.

Source: Dessie Zuria woreda education office, (2014) [11].

The reason for the use of questionnaires are the following, it is very economical, time saving process, covers the research in wide area, very suitable for special type of responses. In addition, it is most reliable in special cases. Questionnaires are written forms that ask questions of all individuals in the sample group, and which respondents can answer at their own convenience (15). Hence, the questionnaires items were prepared in English Language and administered to all participants that they can have skills to read and understand the concepts were incorporated.

Questionnaires collected information from teachers, WEOs and PTA members of the selected sample government secondary schools. The questionnaires were prepared with a five Likert scale such as strongly 1= strongly disagree (SD), 2= Disagree (D), 3= Undecided (U), 4= Agree (A), 5= strongly agree (SA) respectively.

In this research, the questioners were delivered to teachers, woreda education offices and PTA members. The numbers are similar for all these groups and their content is extent of women’s participation, attitudes on gender policy in improving women’s participation in leadership and socio-cultural factors.

Interview is a two-way method, which permits an exchange of ideas and information. According to (2) as cited in Abebe, (2014) “the purpose of interviewing people is to find out what is in their mind what they think or how they feel about something”.

For this study, semi-structured interview questions were prepared for the interviewees and it were conducted with school principals and vice-principals of selected secondary schools to gather more information. Because, semi-structured interview is flexible and allows new questions to be brought during the interview for clarification because of what the interviewee says [28].

Document analysis is one of the data collection tools that were applied by the researcher based on the objective of the study. In this concern, documents related to records of strategies to assign principals and annual statistical reports from Dessie zuria woreda of the schools were collected and analyzed.

Checking the validity and reliability of data collecting instruments before providing to the actual study subject will be the core to assure the quality of the data (53). To ensure the validity and reliability of the instrument to be administering pilot test will be conducted to get technical evaluation of the instrument. Checking the validity and reliability of data instruments is one of the tasks of any research endeavour.

The necessary data for this study was collected using questionnaire, interview and documents. To fix the internal consistency reliability and to check the clarity of the idea in the questionnaire, it was first pilot tested before conducting the actual research. For the pilot study, the researcher prepared 30 items and administered it to 32 randomly selected teachers, PTA, and WEO members from Ayalew Tessema Secondary High School were selected by using simple random sampling techniques, who were not participant of the study.

After the necessary data was collected, it was organized according to its homogeneity, tallied, tabulated and analyzed to answer the basic research questions of the research meaningfully. Both quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods were applied in the study. Quantitative data, which were collected through questionnaire from teachers, WEOs and PTA members, were described in descriptive statistics such as percentages. The data collect through questionnaires will tabulate and analyzed by using percentages, mean and standard deviation. Percentage will used to interpret the characteristics of the respondents and the challenges of women participation in educational leadership (basic research question no.3). Mean and standard deviations will used for organizing and summarizing of the basic research questions N.o.1 and 2. The qualitative data was collected through interview and documents analysis information obtained narration words by triangulating the information that obtained from interview. Finally, the result of the interpretation was discussed and summarized.

In order to conduct the study, the researcher brought a recommendation paper from the university to the school’s principals in order to meet with the respondents and get tangible information.

Researcher respected the culture, norm and personal willingness of the respondents to participate on filling of the questionnaire. Then the principals of the schools create conditions for the researcher to communicate with the respondents. The researcher gives an explanation to the respondents about the objectives of collecting data from them. The data are only used for academic purpose in order to improving women participation in educational leadership in government secondary schools. Finally, the researcher thanked all the respondents that participated during collection of data.

In this chapter, the results of both quantitative and qualitative analysis that were conducted to address specific objectives of the thesis are discussed. The first section of this chapter provides the actual collected quantitative and qualitative data of the sample distribution and personal characteristics of the respondents. The second part deals with the analysis and interpretation of the data obtained through questionnaire, interview and secondary sources regarding the status of women participation in educational leadership in Dessie Zuriya Woreda Government Secondary Schools. Questionnaires were distributed to 30 WEO, 100 teachers, 20 PTAs. Among the 150 distributed questionnaires, all of them were filled and returned. In addition to, interview was successfully conducted with 8 interviewees: 4 school principals and 4 vice-principals. The responses given to each of the questions were analyzed and interpreted and most of the data gathered were organized using tables. Presentation of the data is followed by discussion and interpretation in line with the basic research questions. For the sake of convenience of interpretation, related questions were treated together.

As it was presented in table 2 demographic data of the respondents includes gender, educational background, and position and work experience.

Table 2 revealed that regarding sex, out of the total respondents of 178 (72.65%) of them were males; and 67 (27.35%) of respondents were females. As the sex matrixes shows, the participation of respondents in the secondary schools position was dominated by males. And it could be possible to say not only the principal ship but also the teaching in secondary school is male dominated.

Table 2: Demographic Information of Respondents.

NB. N (Number of responses’), % (percentage of the respondent), (WEO: Woreda Education Office and PTA: Parent Teacher Associations).

The educational level of the respondents from table 2 item 3, indicates that the majority respondents 100 (100%) of teachers, 2 (50%) of principals, 3 (75%) of vice principals, 27 (90%) woreda education offices and 20 (100%)of PTA respondents have first degree holder in addition to 2 (50%) of principals,1 (25%) of vice principals, 3 (10)%) of woreda education offices of the respondents have the second degree holder or master in their academic qualification and none of the respondents were not have diploma. Thus, the selected government secondary schools of the study area were working with qualified teachers and half principals. In this regard [37] stated that secondary schools teachers must be degree holder as the minimum requirement and for principals could have masters of school leadership. This implies as the standards of secondary schools fulfilled in terms of teachers and some leaders or principals. In general, some respondents are first degree holders; and few of them seized second degree.

In terms of current position, 104 (65.82%) males and 54 (34.18%) females were government secondary schools. The great majority of the secondary school teachers, principals, woreda education offices and parent teacher associations were males. And it could be possible to say not only the principal ship but also the teaching in secondary school is male dominated. In the same vein, in educational setting while women hold the teaching staff position, men dominates the highest position of educational leadership [36]. Therefore, it is to be high lightened that due to low educational attainment, societal stereotypes institution barflies that hampers the upward movement of women within organizations.

In support of the above finding, from the document analysis obtained from the study, it was discovered that out of 4 secondary government schools, there is no female school principals and only 2 (50%) were female school vice principals while the majority percentile of school principals consisted of males. This data therefore, reveals that the traditional and gendered nature of management in general, especially school principal ship holds true [43]. Stated that women are persistently absent from the highest and most powerful administrative positions in public school education even though in reality they represent the majority of the teaching profession.

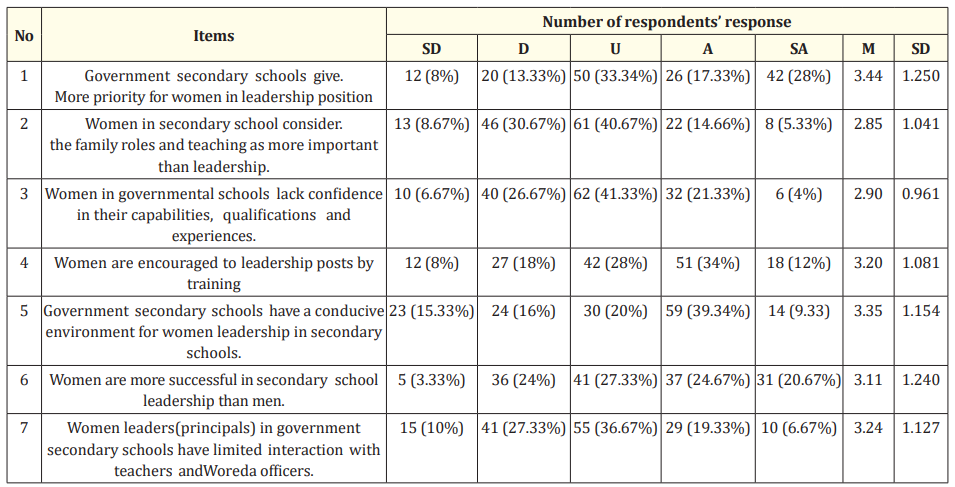

Table 3: Extent of Women’s Participation.

NB. N (Number of responses’), % (percentage of the respondent); SD: Strongly Disagree; D: Disagree; U: Undecided, A: Agree and SA:

Strongly Agree; M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation

As indicated in the table 3, item 1, and respondents were requested rate of agreement on government secondary schools give more priority for women in leadership position. In this regard, respondents of 12 (8%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 20 (13.33%) responded disagree, 50 (33.34%) responded undecided, 26 (17.33%) responded agree and 42 (28%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated it as highly agreed and undecided and they have similar level of agreement on the issue. Based on the response of the respondents the mean value 3.44 which is greater than the expected mean value this means most respondents were responded that schools give more priority for women in leadership. Most respondents agreed for schools there is encouragement to women’s participation in government secondary schools.

As it can be seen from table 3 item 2, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on schools’ women in secondary school consider the family roles and teaching as more important than leadership the respondents indicated that with respect to percentage value 61 (40.67%) were undecided and 46 (30.67%) were disagree. The, mean value of response was 2.85 which is less than expected mean. The result indicates that most of respondents disagreed in their responses; schools’ did not consider the family roles and teaching as more important than leadership.

As it can be seen from table 3 item 3, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on schools’ make women in governmental schools lack confidence in their capabilities, qualifications and experiences the respondents indicated that with respect to percentage value 61 (40.67%) were undecided and the respondents indicated that with respect to percentage value 62 (41.33%) were undecided and 40 (26.67%) were disagree. The mean value of response was 2.90 which is less than the expected mean. The result indicates that many of respondents disagreed in their responses; schools’ make women lack confidence in order to get educational leadership (women are capable and have no capability problem, no lack of confidence due to qualification and experience).

In the same table respondents of 12 (8%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 27 (18%) responded disagree, 42 (28%) responded undecided, 51 (34%) responded agree and 18 (12%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated it as highly agreed and undecided and they have similar level of agreement on the issue. The response to item no 4 indicated that (women are encouraged to leadership posts by training) with a mean value of response was 3.20 which is greater than expected mean. The response in item number 4 showed that most of respondents agreed in their responses women are encouraged to leadership posts by training in government secondary schools.

As shown in table 3 item 5, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on government secondary schools have conducive environment for women leadership in secondary schools. The respondents of 23 (15.33%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 24 (16%) responded disagree, 30 (20%) responded undecided, 59 (39.34%) responded agree and 14 (9.33%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated it as highly agreed and the mean value of response was 3.35 is greater than expected mean. This indicated that most of the respondents in government school agreed there is a conducive environment for women leadership.

As it can be seen from item 6, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on women are more successful than men in order to get school leadership. In this regard, respondents of 5 (33%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 36 (24%) responded disagree, 41 (27.33%) responded undecided, 37 (24.67%) responded agree and 31 (20.67%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated it as undecided, agree and disagree respectively. The mean value of response was 3.11 which are greater than expected mean. The result indicates that most of respondents agreed in their responses; women are more successful in secondary school leadership than men.

As shown in Table 3 item 7, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on women leaders in government secondary schools have limited interaction teachers and woreda officers. The respondents of 15 (10%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 41 (27.33%) responded disagree, 55 (36.67%) responded undecided, 29 (19.33%) responded agree and 10 (6.67%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated highly undecided and disagreed and the mean value of response was 3.24 which is greater than expected mean. In government secondary schools showing that respondents agree with the idea that implies women leaders have good interaction with teachers and woreda officers.

Moreover, the basic data from the schools shows that there is still low participation of women in leadership and even in teaching position in government secondary schools of dessie zuriya woreda.

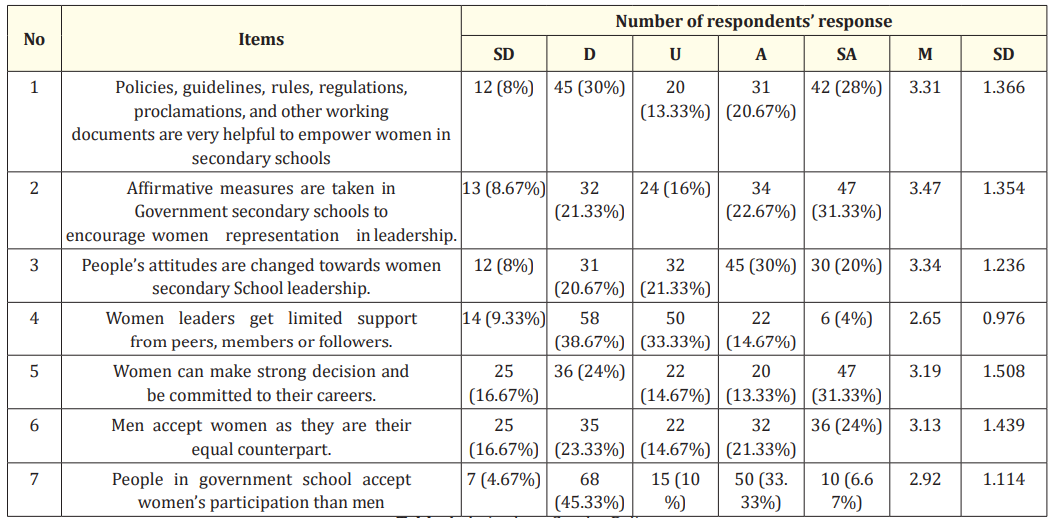

Table 4: Attitude to Gender Policy.

NB. N (Number of responses’), % (percentage of the respondent), SD: Strongly Disagree, D: Disagree, U: undecided; A: Agree and SA:

Strongly Agree; M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation

Table 4 item 1 of government secondary schools respondents 12 (8%) responded strongly disagree, 45 (30%) disagree, 20 (13.33%) undecided, 31 (20.67%) responded agree and 42 (28%) responded strongly agree the respondents were asked that policies, guidelines, proclamation, and other working documents are helpful to empower women in secondary schools. The mean value of response was 3.31 which are greater than expected mean. So, it indicated that the policies and other working documents are very helpful to empower women in secondary schools to become a leader. Moreover from the interview held in the study area. They pointed out the recruitment guideline gives priority for women and also there is special point to encourage women to make them apply to complete and come to the position.

In the same table the response to item 2 affirmative measures are taken in government secondary schools encourage women representation in leadership. In this regard, respondents of 13 (8.67%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 32 (21.33%) responded disagree, 24 (16%) responded undecided, 34 (22.67%) responded agree and 47 (31.33%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated it as strongly agreed and undecided and they have similar level of agreement on the issue. The mean value of response was 3.47 which are greater than expected mean; it shows that there is a better affirmative action taken for women in government. Their response also coincides with the interview responses that the special point for women recruitment.

As shown in table 4 item 3, government secondary schools respondents of 12 (8%) responded strongly disagree, 31 (20.67%) disagree, 32 (21.33%) undecided, 45 (30%) agree and 30 (20%) responded strongly agree the respondents were asked to give their opinion on people’s attitudes are changed towards women secondary school leadership. So, the mean value of response was 3.34 greater than expected mean value. The result indicated that most of the respondents in government school agreed there is people’s attitudes were changed towards women.

As shown in table 4 item 4, government secondary schools respondents of 14 (9.33%) responded strongly disagree, 58 (38.67%) disagree, 50 (33.33%) undecided, 22 (14.67%) agree and 6 (4%) responded strongly agree respondent was asked on women leaders get limited support from peers, members or followers in order to get leadership. The respondents rated it as disagreed and undecided and the mean value of response was 2.65 which is less than the expected mean. This implied that support from peers and follower limited and not the needed amount of support is available.

Table 4 item 5, of government secondary schools the respondents were asked to give their opinion on the women can make strong decision and committed to their careers. The respondents of 25 (16.67%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 36 (24%) responded disagree, 22 (14.67%) responded undecided, 20 (13.33%) responded agree and 47 (31.33%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated highly strongly agree and disagree and the mean value of response was 3.19 greater than expected mean value in government secondary school. Therefore, the respondents agree that women can make strong decisions so, it clearly indicate people agree that women can make strong decision and be committed to their careers.

As shown in table 4 item 6, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on men accept women as they are their equal counterpart secondary school leadership. The respondents of 25 (16.67%) responded were strongly disagree, 35 (23.33%) responded disagree, 22 (14.67%) responded undecided, 32 (21.33%) responded agree and 36 (24%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated highly strongly agree and disagree and agree respectively and the mean value of response was 3.13 greater than expected mean value. The result indicated that most of the respondents did have enough information that could make them decide agree.

Table 4 item7, the response of respondents of the people in government secondary schools accept women’s participation than men. The respondents of 7 (4.67%) responded were strongly disagree, 68 (45.33%) responded disagree, 15 (10%) responded undecided, 50 (33.33%) responded agree and 10 (6.67%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated highly disagree and agree respectively so, the mean value of response 2.92 is not greater than expected mean value. Therefore, this result indicated that people in government secondary schools couldn’t decide as they accept women participation than men. To take this response not to develop positive attitude more clearly women and men participation should be taken equally.

Table 5: Challenges of Women Participation.

NB. N (Number of responses’), % (percentage of the respondent), SD: Strongly Disagree, D: Disagree,

U: Undecided, A: Agree and SA: Strongly Agree.

As indicated in the table 5, item 1, respondents were requested rate if women had provide less training and professional development to women than men of government secondary schools was raised as one challenge. In this regard, respondents of 6 (4%) responded rate were strongly disagree, 42 (28%) responded disagree, 42 (28%) responded undecided, 29 (19.33%) responded agree and 31 (21.67%) responded strongly agree. The respondents rated it as highly agreed and undecided and they have similar level of agreement on the issue. Therefore, the findings indicate that less training and professional development to women than men contributed to hinder women’s participation in educational leadership. That means unequal access to education and training is one of the major challenges that hindering women’s participation in school leadership.

Regarding, the issue of misperception of teachers and other stakeholders to accept women’s leadership in table 5 items 2, the respondents responded that respect to the percentage rate 5 (3.33%) were strong disagree, 36 (24%) were disagree,41 (27.33%) were undecided, 37 (24.67%) and 31 (20.67%) were agree and strongly agree respectively. This implies that there is a little problem of acceptance in government secondary schools.

Table 5, item 3, of government secondary schools the respondents were asked to show their agreement whether the women lack self-confidence or have poor self-image in the study areas. Accordingly, some of the respondents 7 (4.67%) were responded strongly disagree, 68 (45.33%) responded disagree, 15 (10%) responded undecided, 50 (33.33%) responded agree and 10 (6.67%) responded strongly agree. This implies that most of the respondents were disagreed the idea that women lack self-confidence or have poor self-image of women participation in secondary schools.

As indicated in the table 5 item 4, women teachers lack aspiration or motivation to be represented in secondary schools leadership was raised as one challenge. In this regard, 9 (6%) and 54 (36%) of respondents response rate were strongly disagree and disagree respectively. On the other hand, 25 (16.67%) of the respondents response was undecided, whereas 39 (26%) and 23 (15.33%) of respondents responded rate were agree and strongly isagree respectively. Thus, this figure shows it is disagreed there is women lack aspiration to be represented in secondary school leadership.