M Sanjana1 and Ankit Thakur2

1,2Department of Pharmacy Practice, Samskruti college of Pharmacy, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Hyderabad, India

*Corresponding Author: Ankit Thakur, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Samskruti College of Pharmacy, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Hyderabad, India

Received: December 19, 2023; Published: February 18, 2024

Citation: M Sanjana and Ankit Thakur. “Different Types of Therapies in Corneal Regeneration”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 7.3 (2024): 11-16.

The ocular surface is the outermost part of the visual system can experience physical or chemical damage from external or internal factors such as thermal harm, infectious pathogens, and burns, Steven Johnson Syndrome or, other autoimmune diseases. Limbal cells possess stem cell qualities and regenerative capabilities due to their capacity for differentiation. The regeneration of corneal wounds involves a multifaceted process encompassing cell death, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Among various therapies for corneal regeneration, stem cell therapy stands out as the most promising due to its rapid recovery from infections. Although still in its early stages, interventions for treating corneal abnormalities are underway. These interventions involve the use of both viral and non-viral vectors to introduce genes into the cornea, employing in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro methods. This review primarily focuses on the latest advancements utilizing biological modulators like gene therapy, signaling inhibitors, microRNA, and Nano formulations. Additionally, the paper concentrates on the latest therapies utilizing stem cells and advancements in the ocular drug delivery system, aiming to enhance potential therapies for the future treatment of ocular diseases.

Keywords: Stem Cells; Rock Inhibitor; Gene Therapy; Corneal Regeneration; Micro RNA; Corneal Damage

Due to its position as the eye’s outermost layer, the cornea is subject to various environmental strains, including burns, infections, abrasions, and conditions like refractive surgeries, which prompt tissue healing processes. Cornea comprises of 3 types of cells: -the stratified surface epithelium, the stromal keratocytes, and innermost single layer endothelium cells. Following the closure of the defect, the epithelial cells undergo migration, proliferation, and differentiation. These are also accompanied by apopstatis. These keratocytes are replaced by live cells without scarring [1]. Corneal transplantation is done generally but the individual receiving LASIK surgeries also contributes 2% complication with abnormal wound healing. Corneal endothelium unlike other cells repair by cell migration and spreading. Particular attention is placed on the most recent techniques involving biological regulators such as gene therapy, inhibitors of signaling, micro RNA, and Nano formulations [2]. The healing of corneal wounds involves a complicated sequence of events: cells experience death, multiply, migrate, differentiate, and remodel the extracellular matrix. The renewal of the epithelial layer holds significance as it creates a protective barrier, safeguarding the inner cornea from harmful environmental elements [3].

Corneal damage refers to an injury within the eye’s transparent covering, called the cornea, which aids in visualizing objects [4]. About 3% of emergency visits are due to corneal damage. These corneal damages may be mild to moderate and sometimes may also cause vision-threatening. Corneal injuries can be broadly divided into two categories one is traumatic (corneal abrasions and foreign exposure) and second is exposure (burns due to chemical, thermal, radiation) [5]. Damage to the cornea is linked to various conditions, including genetic or degenerative disorders such as conjunctivitis, dry eye, keratoconus, pterygium, cataracts, as well as certain infectious agents [6]. All the agents cause corneal damage in the following pathway.

The corneal epithelium is the softest and smooth part that lacks vascularization and derives nutrients from tear fluid [7]. The extent of burns and infections is determined by how long and intense the damaging agents affect the area. When cornea gets exposed to strong alkaline chemicals it causes liquefactive necrosis of cells while acid burns cause coagulation necrosis [5]. Liquefactive necrosis, involving degenerative neutrophils, causes irreversible damage and is considered more hazardous compared to coagulation necrosis, which arises from protein denaturation [8].

There are three stages in pathogenesis of corneal damage that include

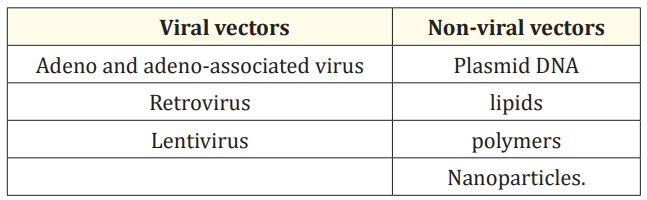

This therapy involves employing genes rather than drugs or surgical procedures to treat the disease. Gene therapy either substitutes the faulty gene causing the condition with a healthy one, deactivates the mutated gene, or introduces a new gene to assist in combating the disease, offering potential treatments for patients [12]. In ophthalmology, the cornea’s transparency and lack of blood vessels make it an optimal tissue for gene therapy, facilitating easier treatment. Despite being at an early stage, interventions for addressing corneal abnormalities are underway. This involves the utilization of various viral and non-viral vectors to introduce genes into the cornea through in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro methods. The list of vectors is mentioned below in table 1.

Table 1: Types of viral and non-viral vectors.

This therapy utilizes methods such as gene gun application, electroporation, intrastromal injection, and iontophoresis to introduce genes, whether through viral or non-viral vectors [13].

Rho kinase (ROCKs) are effectors in the Rho pathway which are serine/tyrosine kinases. The primary function of ROCKs is associated with cell growth, movement, and the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, ultimately resulting in tissue cell death. These ROCKs are expressed in the cornea, involve in corneal healing and cell differentiation. So, the use of ROCK inhibitors will improve corneal wound healing. Corneal endothelial cells (CEC) are the sites of ROCK expression. These cells play a main role in corneal transparency. The utilization of ROCK inhibitors induces the inactivity of these cells, aiding in the facilitation of endothelial regeneration processes.

The main use of ROCK inhibitors can be seen in several conditions where the outcome is increased retinal blood flow and improved vision. The list of diseases where ROCK inhibitors are used are listed below along with outcome

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNA molecules found in multicellular eukaryotic organisms that are important in regulating translational repression of cells [16]. These bind with target mRNAs at 3’-untranslated region for regulating posttranscriptional gene expression. Approximately a quarter (25%) of miRNAs are situated in the eye’s corner and oversee various aspects of corneal functionality, such as development, differentiation, glycogen metabolism, post-injury regeneration, and the maintenance of corneal epithelial progenitor cell (CEPC) balance. In pathological circumstances, these miRNAs also govern conditions like keratoconus and corneal neovascularization resulting from events like corneal transplantation, herpes simplex virus infection, and alkali burns. Consequently, mRNAs have emerged as promising therapeutic targets for treating corneal diseases [17]. miR-143 and 145, as well as miR-10b, 126, and 155, are situated within the basal layers of the limbal epithelium [18].

Amidst the migration and proliferation of corneal epithelial cells, miR-205 plays a pivotal role in promoting corneal healing. It achieves this by targeting SH2-containing phosphoinositide5-phosphatase (SHIP2), consequently influencing the Akt signaling pathway essential for cell migration and enhancing motility by altering F-actin organization. Additionally, miR-205 suppresses the KCNJ10 channel gene, thereby encouraging epithelial cell proliferation. Therapeutically, this approach involves augmenting natural miRNAs, mimicking their natural functions, or employing antagomirs to inhibit their overexpression [19].

In Nano medicine, it includes medical application of nanotechnology, Nano devices (contact lens) and nanoparticles (silicate, gold, silver, platinum, calcium phosphate, etc.), nanomaterial (nanofibers), nano delivery (liposome, dendrimers, polymeric micelles, nano emulsion) in tissue repair and drug delivery for corneal treatment. Nanomedicine in corneal regeneration primarily centers on utilizing materials ranging from 10 to 100 nanometers in size. Its focus includes imaging, as well as the prevention or reduction of corneal opacity and neovascularization.

Nanoparticles utilized encompass various types such as platinum nanoparticles known for their anti-aging properties. Polymeric nanoparticles, composed of polyethyleneimine, albumin, chitosan, and polyethylene glycol, are employed to deliver transgenes to corneal endothelial cells in laboratory settings. Additionally, metallic nanoparticles coupled with polymeric ones, like 2kDa PEI with PEI2-Au-NPs, aid in gene delivery to the cornea in laboratory setups. Meanwhile, non-metallic nanoparticles such as CaP-NPs (calcium phosphate nanoparticles) are both biocompatible and biodegradable. When integrated into the eye, they break down into calcium and phosphate within corneal endothelial cells, facilitating cellular transparency restoration. Nanofibers are used in corneal regeneration when the scaffold-like tissue bridging nanostructures that contain peptides. Upon integration into the cornea, the scaffold’s structure offers a framework that facilitates cell adhesion and migration, thereby enhancing corneal repair. Additionally, a combination of octopamine dendrimers cross-linked with collagen using polypropylene imine supports corneal cell growth and adhesion. Nano devices find primary application in providing prolonged drug release during ocular surgeries. For instance, nanospheres composed of pullulan and polycaprolactone, coated with ciprofloxacin, are utilized primarily for treating infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the eye [20].

The slow healing of corneal epithelium cells in vivo is due to the preservation of their ability to proliferate and the reduction of DNA replication errors. This process unfolds in three distinct ways

Compressed collagen hydrogels were made using the RAFT Reagents. In short, acid-soluble rat-tail collagen was neutralized and diluted to a concentration of 1.6 mg/ml in a solution consisting of 1 × Minimal Essential Medium. This collagen solution, typically 1 ml, was placed into wells of a 24-well culture dish containing 12 mm round glass coverslips. The collagen was solidified in a 37°C CO2 incubator for 1 hour, followed by dehydration for 15 minutes at room temperature using fibrous absorbers in a laminar flow hood. Afterward, the collagen gels were moved to a 60 mm petri dish in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Using a sterile disposable biopsy punch with a plunger, 2 mm diameter disks were punched out for further analysis. Collagen gels without cells were stored in sterile PBS, while those with cells were kept in stem cell growth medium at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for up to 2 weeks. Some gels without cells were stained with Daylight 633 dye before sectioning, rinsed with 0.1 M NaHCO3, and then stained with Daylight 633 NHS Ester reactive dye (0.25 mg/ml in 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.5) for 2 hours at room temperature. Following staining, the CCGs were washed in sterile PBS and stored at 4°C until use [25].

This led to a strong attachment of the compacted collagen to the eye’s surface [26]. This approach offers a quick and practical way to inhibit scarring and facilitate the regeneration of corneal tissue. It proves advantageous for individuals experiencing corneal scarring without any other available treatment options [27].

The corneal endothelium consists of a monolayer of cells derived from the neural crest and mesoderm. Its primary role is to inhibit the development of corneal edema by regulating the function of zonular occludens-1 (ZO-1) and the Na, K- ATPase pump [28]. The Human umbilical cord is a rich source of mesenchymal cells that acts as an allogenic source [29].

Upon initiating differentiation using a medium containing glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3-beta inhibitors, UC-MSCs exhibited a transformation into polygonal structured cells. Validation of the presence of significant corneal markers was conducted using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Western blotting was employed to verify the expression of Na-K ATPase and PITX2 [30].

The Localization of Na-K ATPase and ZO-1 occurs in cell junction which indicates the presence of tight junction. So UTECE may be used as an important source of allogeneic cells for the treatment of corneal disease [31].

The cornea plays a very important role in conducting light into the eyes and protecting intraocular structures. With the impairment of cornea these functions get affected that lead to affecting the internal structures. So it’s very important to maintain cornel health. From the above-mentioned procedures the damage of the cornea can be repaired to most of the extent.

A phase 2 interventional study, which is open-label and singlecentered, commenced on February 9, 2015. Its objective is to assess the safety and viability of utilizing cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cells transplantation to treat limbal stem cell deficiency in approximately 17 patients. The interventional approach involves utilizing cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cell therapy, employing a bio-engineered combination of ex-vivo expanded autologous corneal epithelial cells. Additionally, FDA-approved materials such as an amniotic membrane-like amino graft and Bio-Tissue are utilized for reconstructing the ocular surface. A biopsy of 2 to 3 mm is taken as a source of epithelial cells, which are then expanded on the amniotic membrane in culture and subsequently transplanted onto the cornea after removal of fibro vascular pannus.

In contrast, the study arm procedure entails obtaining a corneal biopsy from the non-diseased eye to acquire cells for the CALEAC graft. Both arms are monitored over a 2-year period to assess safety outcomes, including occurrences of ocular infection, perforation, graft detachment, adverse effects, and the feasibility of achieving cell growth, maintaining cell viability, and preventing culture contamination throughout the 2-year duration [32].

In a randomized, quadruple masked trial focusing on corneal dystrophy including epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and recurrent erosion dystrophy, alongside corneal erosions, the efficacy of CACICOL20® (RGTA OTR 4120) is being investigated. The study aims to assess its effectiveness in enhancing wound healing and nerve regeneration in the anterior cornea among approximately 40 subjects. After undergoing therapeutic laser treatment of the cornea at a single clinic, participants receive either the treatment or a placebo in the form of three eye drops in total, with the first dose administered two days after surgery and the final dose four days post-surgery. Postoperative eye examinations for measurement of various eye and corneal wound healing parameters are conducted on days 2 and 7 at months 6 and 12. The interventional arm includes an investigational device, regenerating agent, single-use doses, and topical eye drops that are indicated for corneal wound healing and other group using a placebo with identical packaging and include dosage and administration route. The experimental group includes Cacicol 20eye drops after laser corneal surgery. A total of three eye drops are to be administered immediately following the surgical procedure. The main assessment measures the percentage of recovery in sub-basal nerve density over a period of 12 months [33].

A combined phase 1/phase 2 study is assessing the safety and effectiveness of an investigational new drug, TTHX1114 (NM141), aimed at regenerating corneal endothelial cells in patients with corneal endothelial dystrophies through intracameral delivery. This study involves multiple centers and is randomized, masked, vehicle-controlled, and includes a dose-escalation design. It incorporates an observational sub-study with 25-50 subjects.

The interventional arms consist of TTHX1114 (NM141), an engineered FGF-1 drug, delivered intracamerally, while other groups receive a placebo. The study arm comprises the following: a placebo comparator vehicle administered weekly for 4 weeks; an experimental group receiving a low dose of TTHX1114 (NM141) weekly for 4 weeks; a mid-dose group receiving TTHX1114 (NM141) weekly for 4 weeks; and another group receiving a high dose of TTHX1114 (NM141) weekly for 4 weeks. The primary outcome measure assesses changes in corneal endothelial cell count over a period of 56 days [34].

The cornea, highly sensitive and prone to infections and injuries, is the primary focus of stem cell therapy. This approach involves using adult autologous stem cells derived from an individual’s bone marrow or adipose tissue to facilitate healing and regeneration of damaged eye tissue. Stem cell therapy eliminates the need for donors or associated complexities. However, ongoing research aims to enhance treatment strategies and eye transplant techniques. It’s important to note that not everyone may benefit from stem cell treatments, especially in cases of severe corneal damage. Effective treatment often relies on the presence of undamaged limbal stem cells in one eye that can be extracted and injected into the damaged eye. Additionally, stem cell therapy becomes more challenging in cases where patients suffer from infections affecting both corneas.

We thank anonymous referees for their usual suggestions.

None.

Not required.

Not applicable.

Copyright: © 2024 M Sanjana and Ankit Thakur. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.