Gajendra Nath Mahato1*, Ipsita Biswas2, Ayub Ali2 and Gouranga Kumar Bose3

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatric Urology, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2 Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Urology, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3 Associate Professor, Assistant Professor Surgery Sheikh Hasina Medical College, Tangail, Bangladesh

*Corresponding Author: Gajendra Nath Mahato, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatric Urology, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Received: April 10, 2023; Published: April 14, 2023

Citation: Gajendra Nath Mahato., et al. “The Outcome of Management of Posterior Urethral Valves”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 6.5 (2023): 21-25.

Background: The most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction in infancy are Posterior urethral valves (PUV) that impair renal and bladder function. This study was planned to evaluate and record the various clinical presentations and management, complications, surgical management and long-term outcome of PUV.

Aim of the Study: This study was planned to evaluate and record the various clinical presentations, management, complications, surgical management and long-term outcome of PUV.

Methods: In this study total, 49 patients who have been treated for PUV were evaluated in Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute from May 2018 to April 2022. Complete data were taken, paraclinical examinations were performed on each patient and diagnosis was confirmed by micturating-cysto-urethrography (MCU). Posterior urethral valves had been ablated in all patients by the electric hook.

Results: 49 patients with a mean age at diagnosis of 42 ( ± 21) days were included in this study. Catheterization was done within one to 5 days of life in 29 patients. PUV ablated all 49 patients by the electric hook. The most common symptom in our group was dribbling poor stream 71% and urinary tract infection (UTI) 46%. There was vesico-ureteral-reflux (VUR) in 52% and hydronephrosis in 92.5%. The most common associated anomaly was kidney anomalies (Renal agenesis/dysplasia and multicystic kidney disease) in 4 (8.2%) patients. About ten patients had a prenatal diagnosis of PUV. Complications occurred in two (4.2%) patients. Mortality occurred in 3 (6.4%) patients. The mean follow-up period was 3.2 ± 0.8 years (1.5 months to 4 years).

Conclusion: MCU is the gold-standard imaging modality for documenting PUVs. Urinary drainage by catheter in infancy, followed by valve ablation, is the best treatment for PUV. The factors like renal dysplasia and UTI have their role in the outcome.

Keywords: PUV; Urinary Drainage; Valve Ablation; Urinary Diversion; Outcome; Children

The most common cause of lower urinary tract obstruction in male infants is posterior urethral valves. The congenital mucosal membrane in the prostatic urethra is called the posterior urethral valves (PUV). It is associated with morbidities, including urinary tract infection (UTI), chronic renal failure (CRF), urinary incontinence and even death, and the incidence is 1 in 4000 to 25000 live births. Some patients with PUV are being diagnosed in utero. PUVs are classified into three types: Valves representing folds extending inferiorly from the verumontanum to the membranous urethra (Type 1), Valves as leaflets radiating from the verumontanum proximally to the bladder neck (Type 2.) and Valves as concentric diaphragms within the prostatic urethra, either above or below the verumontanum (Type3). The most common type is type one. PUV should be evaluated in all males in the family, even in asymptomatic ones. Long-term follow-up for children with PUV is mandatory, even after 20 to 25 years old. In this circumstance, blood pressure, growth and weight, creatinine, urine analysis and electrolytes, urinary tract ultrasonography, diethylene triamine peracetic acid (DTPA) isotope scan, dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) isotope scan, and voiding cystourethrography evaluations are needed. PUV is diagnosed by visualization of the valve leaflets, trabeculated bladder, dilated and elongated posterior urethra, and bladder neck hypertrophy. Mictureting cystourethrogram (MCU) is still the gold-standard imaging modality for documenting PUVs. Urinary drainage by a feeding tube in infancy, followed by valve ablation, is the best treatment for PUV. Surgical management of urethral obstruction is usually done by endoscopic valve ablation. Therefore, post-valve ablation management is essential in improving the outcome of patients with PUV. This study was planned to evaluate and record the various clinical presentations, management, complications, surgical management and long-term outcome of PUV.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Department of Pediatric Urology in Bangladesh Shishu Hospital and Institute from May 2018 to April 2022. Forty-nine patients treated for PUV were included in the study. Most of the patient was diagnosed by ultrasonography, MCU and cystoscopy in all cases and urine analysis, complete blood count (CBC), blood urea, serum creatinine and serum electrolytes. All neonates with urinary retention received all silicon Foley catheters within the early neonatal period and were not cured were treated with fulguration/ablation of the posterior urethral valves by pediatric resectoscope under general anesthesia after valve ablation catheterization was done for five days. DTPA and DMSA isotope scans are checked for hydronephrosis and VUR every 6 to 12 months.

All patients had received injectable ceftazidime (50mg/kg/ BD)/Ceftriaxone (50mg/kg/day) and injection of Amicacine (5mg/ kg/TDS) for seven days. All patients received Nitrofurantoin (1-2 mg/kg/night) as prophylactic and were followed for 3.2 ± 0.8 years with routine tests checked in every visit and MCU performed in those with persistent hydro-ureteronephrosis to check vesicouretral-reflux (VUR).

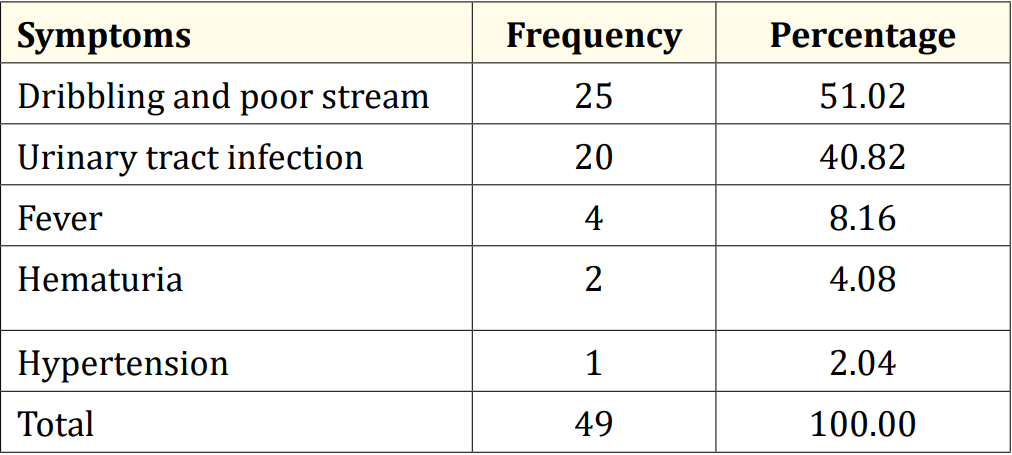

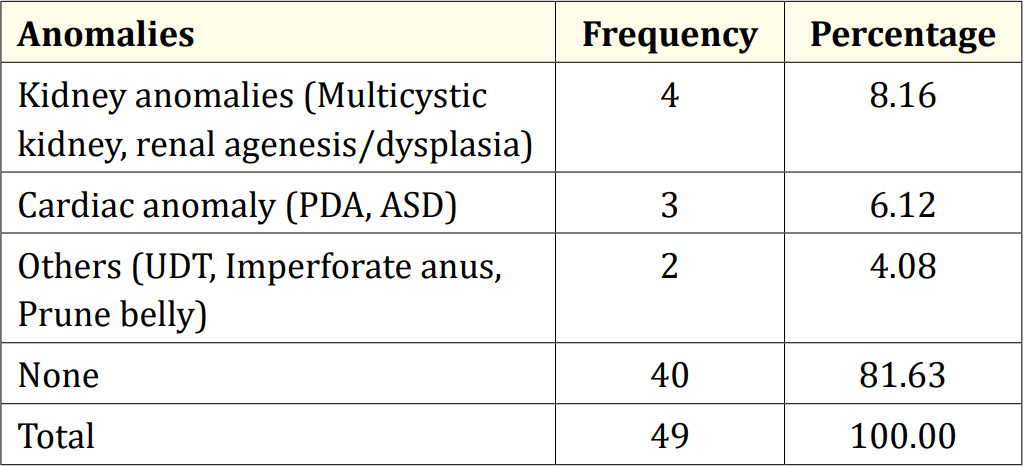

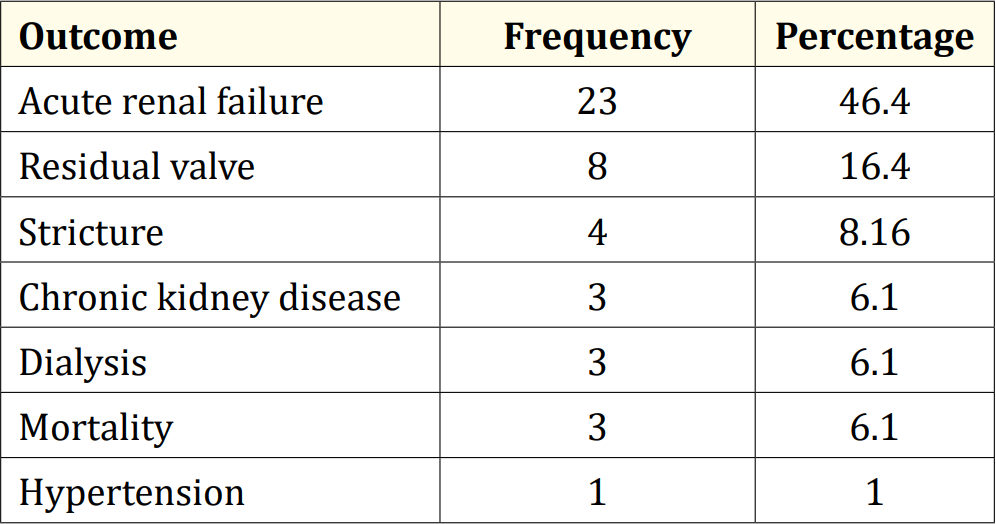

A total number of 49 patients with PUV were included in our study; the mean ± SD age at diagnosis was 52 ± 11 days (one day to two years) thirty patients (66.3%) was less than one month, 28.1% was 1- 12 months and just 4.1% was more than one year. Twelve patients (25.5%) presented with urinary retention. Symptoms and signs in PUV patients are shown in Table 1. Dribbling and poor stream was the most common presenting symptom (51% of patients). The most common associated anomaly was kidney anomaly (multicystic kidney disease and renal agenesis/dysplasia) in 4 (8.2%) patients (Table 2). We had to catheterise by all silicon Foley,s Catheter 6 FR, 49 patients to relieve obstruction, standard urine stream, and the correction of urea, creatinine and electrolytes. VUR was presented in 30 (61.2%), of which 15 cases had bilateral and 16 unilateral reflux (VUR grading was V = 9 units, IV = 11 units, III = 10 units, II = 11 units, and I = eight units). Hydronephrosis presented in 41 (82.7%) patients being mild (15 units), moderate (16 units) and severe (18 units). DTPA at follow-up of our cases showed persistent upper tract dilatation (mostly unilateral) with mild to moderate functional obstruction in 5 patients, which improved later. PUV was diagnosed in 10 (20%) patients prenatally. All patients were treated with fulguration/ ablation of PUV by a pediatric resectoscope under general anesthesia. Forty cases had type one PUV. With the urethral catheter, 22% of cases showed improvement in renal function (fall in serum creatinine level). The mean follow-up period was 3.4 ± 1.2 years (1.5 months to 5 years). Complications occurred in Two (4.2%) patients who had extravasation of urine due to kidney perforation, which was managed by temporary vesicostomy. 3 (6.2%) patients died due to renal failure (2 patients) and urosepsis (1 patient). The long-term outcome of our study is presented in Table 3.

Table 1: Symptoms and signs in posterior urethral valve patients.

Table 2: Associated anomalies in posterior urethra valve patients.

PDA: Patent ductus arteriosus; ASD: Atrial septal defect; UDT: Undescended testis

Table 3: Long-term outcome of posterior urethral valves.

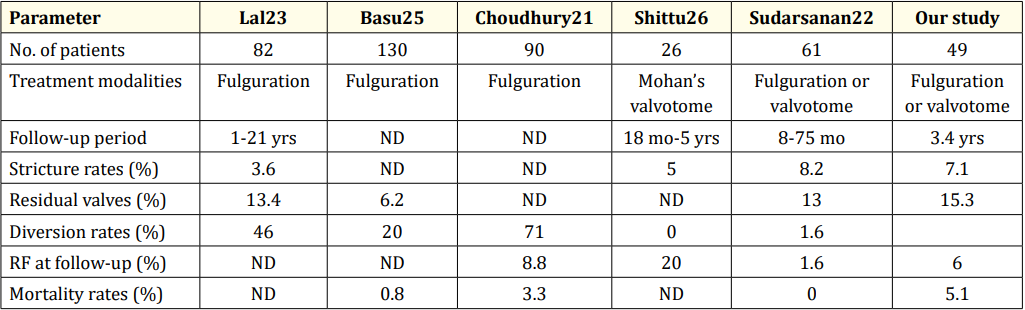

ND: Not documented; RF: Renal failure

Table 4: Comparison with other studies of PUV patients.

PUV is the most common cause of lower urinary tract obstruction in male children. The severity of PUV varies from mild to severe, according to the degree of obstruction [11]. Complications may develop in the patient even after valve ablation and long-term follow-up. Management of PUV needs adequate neonatal and infant care with nephrological support to treat Urinary tract obstruction and correct metabolic acidosis and electrolyte imbalance if necessary [12,13]. Improved management of patients with severe PUV has resulted in better long-term outcomes [14]. There are three anatomical variables in PUV which may provide a “pop-off” mechanism: 1) urinoma/urinary ascites, 2) syndrome of PUVs, 3) PUV+ large congenital diverticular, that results in preservation of intact renal and bladder function [14-16]. Urinary ascites result from urine leakage from the urinary system, and usually, there is a high level of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine [17]. In this situation, the pop-off mechanism preserves the kidney from excessive pressure and is an excellent prognostic sign [14,15,18]. We had two cases of urinary ascites in our study, which improved by temporary vesicostomy. Patients who failed to respond to urinary catheter drainage, associated severe VUR, and urinary leakage, finally required diversion [19,20]. Associated anomalies in posterior urethral valves patients four (96%) patients of our study group were in the first year of life; in Choudhury., et al. study, 77%, Were in this age group and Malik., et al. series less than 30% [2,21]. The incidence of renal failure at presentation is reported as 6690% in the literature, but in Choudhury., et al. group, it was 71%, and in our series, 46%, of which 6.1% required dialysis [20]. The most common symptom in Malik., et al. study was associated fever (72%), whereas, in our group, it was a dribbling and poor stream (51%) [2]. In our cases, there was 61.2% VUR (right 10.2%, left 20.4% and bilateral 30.6%), while it was 22% (16% left and 6% bilateral) in Malik., et al. and Sudarsanan., et al. had 12 bilateral VUR and eight hydronephroses. In our study, VUR subsided within 3 to 4 months in most cases post valve ablation. UTI was present in 40.8% of our patients, cured by antibiotics, and in severe/ resistant cases with diversion [2,22-24]. DTPA at follow-up of our cases showed persistent upper tract dilatation (mostly unilateral) with mild to moderate functional obstruction in 10 patients, which improved in later follow-up. Our long-term outcome of PUV patients is presented in Table 3 and compared with other studies in Table 4 [21-23,25,26]. The reported incidence of stricture following endoscopic ablation is between 3.6 to 25% [21]. An incidence of 7.1% means an improved result in our study. Our residual valve incidence rate was higher than the other reports; it may depend on our technique, available instruments, or both. Our diversion rate and renal failure at follow-up were acceptable compared to the other studies, but the mortality rate was higher than in other reports.

Urinary drainage by catheter in infancy, followed by valve ablation, is the best treatment for PUV, and urinary diversion improves the outcome. MCU is still the gold-standard imaging modality for documenting PUV. The factors like renal dysplasia and Urinary tract infection have their role in the outcome.

Copyright: © 2023 Gajendra Nath Mahato., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.