Riva G1*, Monestier L2, D’Angelo F3, Ambrosio MC4, Discalzo G2 and Surace MF5

1 Pediatric Orthopaedics Unit - Division of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Varese, ASST Sette Laghi, Italy

2 Division of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Varese, ASST Sette Laghi, Italy

3 Division of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Varese, ASST Sette Laghi, Italy - Department of Biotechnologies and Life Sciences, Università Degli Studi Dell'insubria, Italy

4 Division of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Università Degli Studi Milano Bicocca, Milano, Italy

5 Orthopaedics and Trauma Unit, Cittiglio-Angera, ASST Sette Laghi - Department of Biotechnologies and Life Sciences, Università Degli Studi Dell'insubria, Italy

*Corresponding Author: Riva G, Pediatric Orthopaedics Unit - Division of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Varese, ASST Sette Laghi, Italy.

Received: December 14, 2022; Published: January 19, 2023

Citation: Riva G., et al. “Forearm Refracture in Children: May the Rate be Reduce by K-Wires?”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 6.2 (2023): 16-20.

Refracture is a frequent complication of both bone shaft fracture; although many risk factors have been suggested by different authors during the years, refracture rate remains surprisingly high. Intramedullary pining, with K-Wire or ESIN, has proven to be an effective treatment to restore original anatomy and stabile forearm fracture, but its efficacy in reducing refracture rate is questionable. In our study we assessed retrospectively a cohort of 87 patients treated surgically by intramedullary pinning with K-Wires analyzing the potential of this surgical strategy in reducing refracture indicidence.

Keywords: Both Bone Forearm Fracture; Refracture; K-Wire; Risk Factors.

Both-bone forearm fractures are very common in childhood and treatment shows generally good outcomes [1] [2]: callus remodeling allows to restore original bone resistance and shape. Refracture is a frequent complication, and its pathogenesis is still debated [3].

The aim of this retrospective study is to assess trends of refracture, with particular emphasis on etiology and possible risk factors.

One hundred and twenty-eight children were treated for both-bones shaft forearm fractures in our Orthopedics and Traumatology Unit (ASST dei Settelaghi, Varese, Italy) between 2008 and 2018.

In this study, we included only patients who underwent to closed reduction and stabilization of with percutaneous intramedullary pinning (K-wires).

At follow up, forty-one patients were lost. Therefore, eighty-seven patients were included: sixty-three were males (72.41%) and twenty-four females (27.59%). Average age at surgery was eight years (2÷16). Fracture were unilateral in all the cases: eighty-four were closed fracture (96.55%) while three Type-1 open fracture (3.45%), according to Gustilo-Anderson classification [4]. Fractures were topographically divided according to Kubiak criteria, into proximal third, middle third and distal third [5].

In twelve patients (13,79%) a single pin was used; contrarily, two K-wires were positioned in seventy-five (86,21%); diameter varied from 1.4 mm to 2 mm. After surgery, forearm was protected by a brachio-metacarpal cast.

We usually prefer to leave the tip of K-wire out of skin, in order to facilitate its removal. Ambulatorial medications were performed every week.

Clinical and radiological follow ups were performed at 1 month, 2 months and 3 months, eventually 6 months and at the time of the study; AP and LL x-rays were collected. Pins were removed according to radiological consolidation criteria.

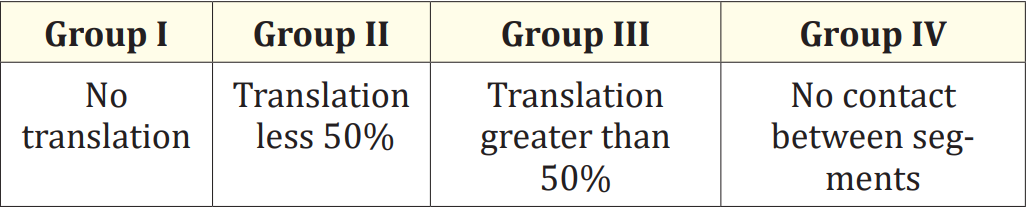

Radiologic assessment on x-rays was performed by dedicated measuring tool of our PACS software, Sinapse® (Fuji, ver.4.1, 2012). According Colaris [6] criteria, for each forearm bone we evaluated

Table 1

Finally, according to Bronstein criteria [7], we measured post-reduction ulnar variance: we distinguished in patients with more or less of 5mm positive ulnar variance, to identify possible prono-supination deficits.

Fracture not healed within three months by surgery, but consolidated at six months, were defined as «delayed» [8]; according to Tisosky, we considered a recurrence a fracture that occurs at the same site of the original fracture, within eighteen months from the initial traumatic event [3].

SPSS Statistics® software (version 20.5, 2017) was used for statistical analysis.

The mean cast time was seventy-one days (24 ÷ 120); pins were removed as soon as X-rays assessment suggested an advanced bone consolidation on a mean time of fifty days after fracture (30 ÷ 90); after K-wires removal, a further cast as eventually applied in case of poor bone callus.

Figure 1: Fracture and healing then refracture and new treatment.

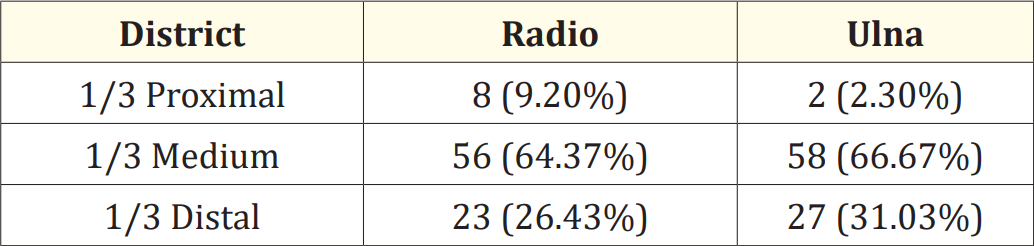

According to Kubiak criteria, fractures were distincted into: (Table 2).

Table 2

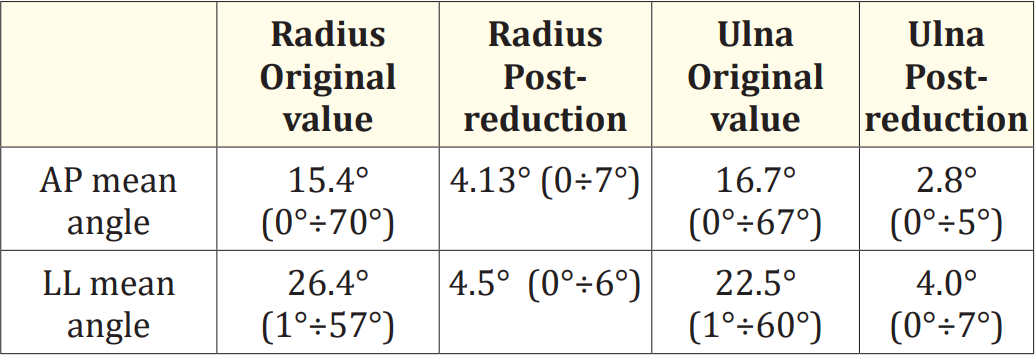

Severely displaced fractures were thirty-one (35.63%): the displacement involved both the bones in twelve patients (13.80%), only radius in fifteen (17.24%) and only ulna in four (4.60%). Pre- and post-reduction displacement mean angles are summarized in table 3.

Table 3

The analysis of post-reduction residual lateral translation produced the following results (Table 4).

Table 4

Shortening of the radial proximal epiphysis, compared to the proximal epiphysis of the ulna, was greater than 5 mm in 3 patients (3,4%).

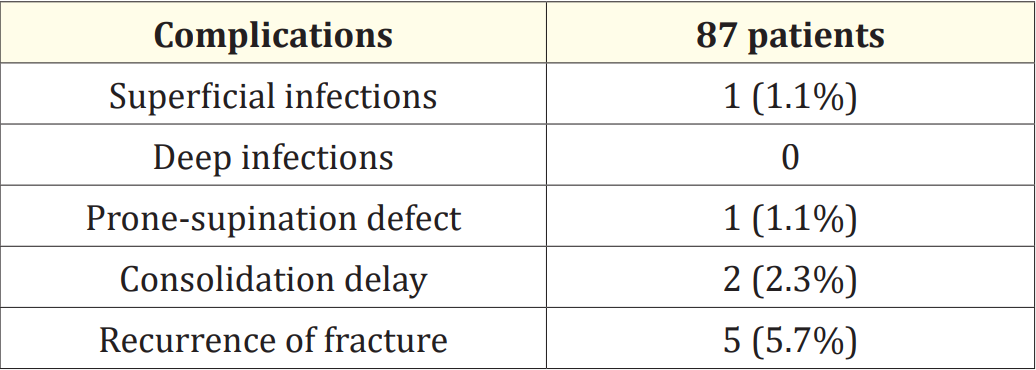

Complications were observed in 9 patients (10.3%).(Table 5)

Table 5

No deep infections were observed; the only patient with superficial wound infection was treated with specific antibiotic therapy protocol (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid), with complete healing in a week.

Delays in consolidation were observed in two patients, involving the radius in one case and the ulna in the other; both achieved complete bone healing at six months without any further treatment.

Refracture were observed in five cases (5.75%): the mean time of recurrence after the primary fracture was 134.42 days (95 ÷ 187); middle shaft third was involved in four cases (4.60%), while distal third in the other case (1.15%).

Both-bone forearm fractures of the forearm shaft are very frequent in pediatric age, with a prevalence of 10% to 45% of all pediatric fractures [3]; the most common injury mechanism is an indirect trauma, caused by a fall with an excessive load applied to an extended forearm through the hand. Refracture is even common [3,9], with a prevalence variable from 1.7 to 14.7%. This complication has been known for many years [10,11], but mechanism and risk factors are not completely understood: many authors suggested that residual forearm angulation, incomplete fracture remodeling, midshaft location and younger age could play a substantial role in refracture etiology [9,12], but despite their identification and the increasing diffusion of surgical techniques, the incidence of refracture remains relatively high (4% and 8%) [3,13].

Residual deformity could be a risk factor both for mechanical and biological reasons: a load applied longitudinally to angulated segment tends to break the segment at the level of angulation as well as bone remodeling tends to be longer in displaced fracture [3,13]. Surgical treatment, in particular intramedullary pinning (ESIN or K-Wires) should guarantee better reduction [5] and lead consequently to an improvement of the refracture rate. As aforementioned, refractures’ rate varies from 4% to 8%, regardless the type of surgical treatment; for example, in our cohort we recorded five refractures, with a prevalence rate of 5.7%; but, surprisingly, Tisosky., et al. reported a substantially lower rate of refracture of 1.7% in group of patients treated conservatively [3]. Moreover, in our study there are no statistical correlation residual angulation, residual translation or prono-supination defects by altered ulnar variation and refracture (p = 0.839): thus, intramedullary pinning doesn’t appear as an effective method in reducing the risk of refracture; probably, angular deformity tends to be a risk factor only if significative: specifically, Baitner et suggested that a residual forearm angulation wider than 21° [8] could be associated to an higher rate of refracture; contrarily, Tisosky sets this limit at 10° [3]. We suppose that lower residual deformity seems to be a minor factor.

Incomplete fracture remodeling is advocated be a key role in refracture; for this reason, some orthopedic surgeons often decide to continue intramedullary pinning for long period, to protect callus remodeling and reduce the prevalence of refracture. Nonetheless, maintaining K-wires for longer period hasn’t been correlated with lower refracture rate, neither in our study (p = 0.347) nor in literature [13-15]. Hypothetically, a longer immobilization with cast or plaster may protect callus from mechanical stress and support consequently the remodeling process. However, in our study, time of immobilization does not influence the rate of refracture (P = 0.699); similarly, in 2018 Han., et al. did not find any significative differences between immobilization shorter or longer than six weeks [13]. Contrary, Bould reported increased risk of refraction in cases of immobilization shorter than ninety days [9].

In our cohort, most cases of refractures (4/5, 80.00%) occurred in middle shaft third, suggesting that this location is a significative risk factor. This result is similar to literature [3,8,13] The reasons higher rate of refracture in midshaft may be twofold: firstly, the healing process in middle third is slower than metaphysis; secondly, deforming forces have a greater leverage at that point. Probably this latter is the crucial risk factor, but, unfortunately, we cannot do anything to reduce prevalence of midshaft fracture.

No significative correlation was found between refracture and K-wire diameter, initial displacement or open fracture (p>0.05); we believe that these aspects could influence healing time, delayed unions or non-unions but not refracture rate. Casts, plasters and braces could not be applied for all the time of bone remodeling. Similarly, intramedullary pins, both k-wires and TEN, could not be maintained for all the time of process, because it is recommended removed them within 6 months [5].

In our study, the mean time of refracture from the trauma was 134,4 days; in literature this value varies between ninety days and six month [3,13], usually earlier onsets are reported in study concerning only conservative treatment [3]. Refracture is usually far later (three months) than cast removal and this is probably the reason why immobilization does not seem to be protective enough; a recent study from Soumekh., et al. [16] would confirm this our impression: the Authors conclude that a prolonged casting did not lead to a statistically significant difference in refracture rate.

Basing on these aforementioned observations, we believe that the most important risk factor is the event of an «effective trauma», whose deforming forces exceed mechanical strength of a not completely remodeled callus, even more in forearm midshaft for its significative lever arm.

Surgeon should firstly achieve the best reduction possible (below 10° of displacement), then pay his attention to limit possible effective traumas by avoiding traumatic sport activities for longer periods (six-nine months).

In our study, refractures occur in younger children: the reason may be their lesser awareness and proprioception that could lead to an higher risk of incidence of effective trauma and this is confirmed by most of studies in literature [9,12,13] It’s very difficult to limit risky activities in a small child without pain34 occurred within nine months at the original fracture site. The median time to refracture was eight weeks after discontinuing cast immobilisation. Diaphyseal fractures were eight times more likely to refracture than metaphyseal fractures. The risk of refracture was inversely proportional to the duration of cast immobilisation. Cast immobilisation for a minimum of six weeks reduces the risk of refracture by a factor of between four and six. Midshaft forearm fractures are at risk of refracture for sixteen weeks from cast removal. Copyright (C. Baitne., et al. reported how the risk of refraction is almost doubled in children who use toys with wheels, such as skates, scooters, skateboards and the like [8].

In our study, the patient’s gender was not related with refracture incidence (p = 0.746), even if most of patients were male (75%), usually more involved in contact sports. Han., et al. found a correlation between male gender and refracture, hypothesizing that reasons the increased rate lie in male trend tend to perform activities at higher traumatic risk (e.g., contact sports) [13].

Concluding, the answer at the initial question <<does the use of K-Wire could reduce refracture rate?>> is probably yes.

The use of intramedullary pins helps to have better reduction e less residual deformity, especially in midshaft fracture, reducing thus risk of refracture; however even in case of perfect anatomical restoring, the rate will probably remain high, regardless of time of maintenance of pins or of immobilization.

In our opinion, the only way to make the prevalence of refracture, is to reduce the incidence of effective traumas in the first 9 months, avoiding risky sport activities.

Copyright: © 2023 Riva G., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.