Pushpom James*, Steven Daoud, Seleshi Demissie, Raisa Saab and Philip Roth

Department of Pediatrics, Staten Island University Hospital Northwell Health, Staten Island, New York, USA

*Corresponding Author: Pushpom James, Department of Pediatrics, Staten Island University Hospital Northwell Health, Staten Island, New York, USA.

Received: June 15, 2022; Published: July 27, 2022

Citation: Pushpom James., et al. “Does the Treatment of Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis Decrease the of an Obstructive Sleep Apnea Work-up and Treatment?”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 5.8 (2022): 15-22.

Introduction: Obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is an independent risk factor for asthma exacerbations [1]. Since there is an overlap in symptoms between OSAHS and bronchial asthma, with good control of a patient’s asthma and allergic/ non-allergic rhinitis, there should be fewer patients warranting work-up and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea.

Methodology: The goal was to determine the change on the sleep related breathing disorder scale (SRBD) once a patient’s asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis had been controlled [2]. Two questionnaires were administered on patient’s first visit, the SRBD scale and depending on age, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or Childhood ACT. These questionnaires were readministered on a subsequent visit once their asthma and allergic rhinitis were controlled [3].

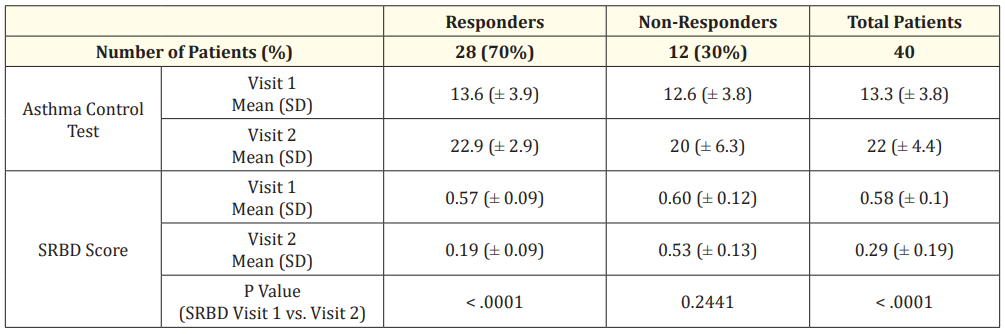

Results: A total of 68 patients were recruited. 40 completed 2 visits according to protocol. Of these, 28, that is 70% of patients showed improvement on the SRBD scale once their asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis were controlled.

Conclusion: By controlling a patient’s asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis, we can increase the specificity of the SRBD scale in asthmatics. This may improve screening for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea in children with asthma with more appropriate usage of diagnostic tools such as polysomnography and perhaps decrease the use of unnecessary treatments and surgeries, such as, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy.

Keywords: Asthma; Pediatric Pulmonology; Obstructive Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome; Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire; Asthma Control Test; Otolaryngology.

OSAHS: Obstructive Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome; SRBD: Sleep Related Breathing Disorder Scale; PSQ: Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire; ACT: Asthma Control Test; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea is an independent risk factor for asthma exacerbations. OSAHS could result in neuromechanical reflex bronchoconstriction, trigger gastroesophageal reflux, and result in local and systemic inflammation which could all result in deterioration of asthma control in patients with concomitant obstructive sleep apnea. Airway angiogenesis induced by vascular endothelial growth factor, and OSAHS induced weight gain could be further linking these two disorders. Leptin resistance in OSAHS could increase parasympathetic tone and result in bronchoconstriction. The proinflammatory effects of leptin could promote airway inflammation [4]. Several studies have confirmed that asthmatic patients are more likely to develop symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea [5]. Nasal obstruction due to allergic/non-allergic rhinitis, a decrease in airway diameter with an increase in airway collapsibility in asthmatics would promote development of OSAHS [1].

An article by Ehsan., et al. in Pediatric Pulmonology demonstrated that the sensitivity of the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) is reasonable in asthmatic children and comparable to previous studies in the general pediatric population, but the specificity is low [6].

Parents are likely to answer “Yes” to many of the questions, when their child has symptoms of asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis that are not well controlled. A child with asthma may be nasally congested due to allergic rhinitis or sinusitis. This may result in mouth breathing, greater negative pressure being generated behind the uvula and soft palate, and cause structures to vibrate. In a child with smaller airway dimensions, this may result in snoring [7]. Furthermore, episodes of nocturnal asthma, coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath result in sleep disruption, restless sleep, and heavy breathing. With poor sleep, subclinical performance in academics could be a manifestation of asthma as opposed to OSAHS.

Ultimately, the benefit of using the SRBD scale as a diagnostic tool for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in asthmatics is limited due to the overlap in symptoms between asthma and OSAHS. Yet with improved control of a patient’s asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis symptoms, it will be easier to determine which patients truly require further evaluation and treatment for OSAHS.

This was a prospective cohort study of pediatric patients with persistent asthma who had symptoms suggestive of OSAHS. This was conducted at the Cohen Children’s Northwell Health Physician Partners Pediatric Specialists at Hylan Boulevard. The Institutional Review Board of Northwell Health approved this study. Patients between the ages 4 to 18 presenting for evaluation and management of asthma seen in the outpatient setting were screened by the principal investigator. If a patient was already being treated for asthma, or if they had symptoms suggestive of intermittent asthma, they were excluded from the study. If the SRBD scale was administered and findings were not suggestive of OSA, these patients were also excluded. Patients were further excluded at the discretion of the principal investigator, if it was deemed their symptoms warranted an immediate overnight polysomnogram.

Ultimately, patients with poorly controlled asthma based on the questionnaire equating to a score of 19 or less on the (ACT) or the Childhood ACT, and a score of 0.33 or greater on the SRBD scale were selected to participate. This prospective study posed no more than minimal risk to subjects as they received standard of care treatment.

All subjects were consented and assented as appropriate before they were enrolled in the study. Assent was obtained from subjects between 7-18 years of age. On the first and second visit, patients were provided the standard of care including a complete history, physical examination and appropriate diagnostic testing. The SRBD scale and the ACT or Childhood ACT for children younger than 12 years were administered. The SRBD scale and the ACT or Childhood ACT were re-administered when they returned for a second visit, between 2 to 12 weeks after the initial visit, once it was deemed their asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis symptoms were controlled. If the patient had not been receiving prescribed medications, or it was deemed that further measures were needed for optimal control, patients returned for a third visit within the 12-week window. Patients were therefore their own control.

Once the data was collected it was recorded on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). All patient health information was recorded, but not disclosed.

The primary outcome variable is the percentage of patients who test positive for sleep apnea (as measured by the PSQ questionnaire) at a follow-up visit post treatment. When the sample size is 62, a two-sided 95.0% confidence interval for this proportion using the large sample normal approximation will extend 10% from the observed percentage for an expected percentage of 80%. Considering the possibility that 30% of patients will be lost to follow-up, approximately 80 patients will be recruited. In order to obtain 80 patients who test positive for sleep apnea at the initial visit, approximately 100 patients will be enrolled into the study. An interim analysis was scheduled after 40 patients had completed two visits.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized for all patients and by study group. Descriptive statistics (number of patients, mean, standard deviation, median and range) were provided for continuous variables. Frequency distribution and percentages were provided for categorical variables. The primary outcome was analyzed using a one-sample test of proportion. A 95% confidence interval will be used to test the hypothesis that the percentage of patients who test positive for sleep apnea using the PSQ questionnaire at a follow-up visit post treatment will be 80%. All statistical tests of significance were two-sided and conducted at the 0.05 level of significance. Data analysis was conducted using SAS (Statistical Analysis System) Version 9.3.

The primary outcome variable was the percentage of patients who tested positive for OSAHS as measured by the SRBD scale at a follow up visit post-treatment. The primary analysis was a one sample test of proportion.

Of the 68 recruited, a total of 28 patients or 41% were lost to follow-up and therefore disqualified. The expected percent loss to follow up was 30%, which is the average no show rate at the outpatient pulmonary practice where patients were recruited. On interim analysis, a total of 40 patients were enrolled from 02/04/2015 to 10/18/2018. Demographic information on these subjects are listed in table 1. 28 patients demonstrated improvement on the SRBD scale.

12 patients, 30% did not demonstrate improvement. The ACT and SRBD scores of patients, both responders and non-responders can be found in table 2, showing no significant difference in the scores of responders compared to non-responders at the time of Visit 1, which precluded predicting the likely responders.

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of study Population.

Table 2: Analysis of outcomes measures for patients who met inclusion criteria and completed two visits.

Upon reviewing the SRBD scale, several questions demonstrate an overlap in symptoms with patients who are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), or developmental delay. For example, the questionnaire asks does the patient “fidget with hands or feet or squirms in seat,” which is a habit often exhibited in ADHD. This overlap in symptomology could preferentially select for this subset of patients. Of the patients recruited a total of 12 demonstrated some form of developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, or ADHD accounting for 30% of those enrolled in the study. However, children diagnosed to have ADHD, developmental delay or autism spectrum disorder appeared just as likely to have a negative SRBD scale score as those children who were thought to be developmentally appropriate for age and without symptoms of ADHD. Lack of detailed diagnoses on all members of this subgroup precluded further conclusions.

OSA is defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine as “a disorder of breathing during sleep characterized by prolonged partial upper airway obstruction and/or intermittent complete obstruction that disrupts normal ventilation during sleep and normal sleep patterns.” [8]. The prevalence is reported as being between 2-3%, in middle school children [9].

Asthma, a common chronic childhood disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), affects 8.3% of children in the United States.

It is well known that there is an interplay between symptoms of pediatric asthma and OSA. There have been hundreds of articles detailing the fact that treatment of OSAHS, improves asthma control. Though the numbers in this study are small, this is the first article demonstrating the fact that control of asthma improves symptoms suggestive of OSAHS.

Significant and independent association was present between snoring and allergic rhinitis with an odds ratio of 5.27 (95% CI, 1.57-17.77) [10].

Ross., et al. showed that among 108 children 4 to 18 years who were recruited from an asthma clinic, 29.6% of children had sleepdisordered breathing. Among those with OSA, there was a 3.6-fold increased odds of having severe asthma at follow up [8]. This suggests that presence of OSA could predict asthma severity [11].

Not only does there appear to be an overlap in symptoms, but recent studies have demonstrated a possible cause and effect association between asthma and obstructive sleep apnea. Teodorescu., et al. demonstrated that preexisting asthma was a risk factor for developing OSAHS, and the longer a patient had asthma, the higher the incidence of OSAHS later in life [12].

Nighttime symptoms suggestive of OSAHS are loud snoring, snorting, gasping, and episodes of apnea, restless sleep, diaphoresis, heavy breathing, paradoxical breathing, and nocturnal enuresis. This lack of adequate sleep may result in behavior problems and decreased attention span [13].

A child with asthma who is coughing, wheezing, experiencing chest tightness and shortness of breath may have sleep disruption, heavy breathing at night, be diaphoretic and be difficult to awaken in the morning. There may be excessive daytime sleepiness, irritability, and poor attention span. A child with asthma may snore, mouth breathe and have a dry mouth upon awakening [14].

The Asthma Control Test (ACT) is a way to help determine if asthma symptoms are well controlled, with a composite score over 19, implying that asthma symptoms are well controlled (Appendices B1 and B2) (see table 2) [2].

The Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire is a 67-item questionnaire validated for children between 4 to 18 years of age. The 22 item SRBD scale was shown in the research setting to have a sensitivity of 0.85 and a specificity of 0.87 (Appendix A) [2].

The 22 questions of the SRBD scale can be answered “Yes” equivalent to 1, “No” equivalent to 1, or “I don’t know” equivalent to zero. The number of symptoms positively endorsed are divided by the number of items positively and negatively endorsed, excluding missing responses or items answered, “I don’t know.” The result equates to a number between 0 to 1. Scores over 0.33 are considered positive and suggestive of a high risk for pediatric sleep related breathing disorder. This threshold is based on a validity study that suggested optimal sensitivity and specificity at the 0.33 cut off [2].

While research is ongoing and the exact relationship between asthma and sleep apnea is not fully understood, various tools have been established to assist clinicians, including the SRBD scale. Increasing awareness of the lack of specificity of the SRBD scale in children with poorly controlled asthma is essential, as this would decrease the number of asthmatics receiving empiric treatment and unnecessary evaluation for symptoms suggestive of sleep disordered breathing. This study demonstrated that a high percentage of patients no longer warranted further work-up or treatment once their asthma and allergic/non-allergic rhinitis were well controlled.

As there are limited resources and a lack of access to pediatric sleep studies, we can better utilize this expensive study. Furthermore, if a child does have an overnight polysomnogram when their asthma is poorly controlled, it can result in insufficient sleep due to nighttime cough and awakenings leading to poor and inaccurate results. The child and parent maybe unnecessarily subjected to the stress of having an overnight polysomnogram, when waiting for improved control can completely obviate the necessity for this study. Controlling a patient’s asthma and allergic/nonallergic rhinitis may reduce the number of patients who undergo tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy unnecessarily for symptoms that are presumed to be related to OSA. A study by Sanchez., et al. in the Journal of Asthma and Allergy demonstrated that adenotonsillectomy improved asthma control but stated that since the relationship appeared to be bidirectional, the impact of asthma treatment on OSAHS needed to be looked at [5].

One of the limitations of this study, is the high loss of patients to follow-up. This may have selectively decreased the percentage of patients who improved after treatment of their asthma and allergic rhinitis. Several patients returning after the 12-week window of the study, were determined to have a negative SRBD scale score [16]. Part of the loss to follow-up was due to the short window for the second visit. We allowed only a 12-week window for the child to be seen for a follow-up to be sure that the change in the SRBD scale score was likely due to improved asthma control. We know from the CHAT trial that 7 months of watchful waiting resulted in 42% of patients no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis of OSAHS on a polysomnogram.

Another limitation is that it is known that nasal steroids and montelukast decrease the AHI [17]. Therefore, when these medications were used to treat bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis, they were simultaneously treating OSAHS. In addition, because these patients were recruited from a single pediatric pulmonology practice, the data may not be generalizable.

Effective treatment of asthma and allergic rhinitis resulted in a 70% decrease in children screening positive for OSAHS on the SRBD scale. This would be important to disseminate as overnight polysomnograms are frequently performed on children with poorly controlled asthma, resulting in overutilization of a scarce resource as well as poor quality studies. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, the first line treatment of OSAHS in children could perhaps be avoided in many asthmatic children, as their sleep disturbance may resolve once asthma was controlled.

The authors wish to thank the following individuals for their tireless efforts and dedication in helping to complete this study: Guiseppina Andrawis, Samantha Bonello, Ashley Kyle and Anthony Gonzalez.

All research and work were performed at the Cohen Children’s Northwell Health Physician Partners Pediatric Specialists at Hylan Boulevard, Staten Island, New York. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript for submission. This study did not receive financial support. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest. This study is not part of a clinical trial.

Appendix A: Permission obtained from Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Appendix B1

Appendix B2

Copyright: © 2022 Pushpom James., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.