Shahram Sadeghvand1, Parya Tobeh2, Akbar Molaei3* and Roghyieh Ebrahimi1

1 Neurology Division, Department of Pediatrics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2 Department of Pediatrics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3 Cardiology Division, Department of Pediatrics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

*Corresponding Author: Akbar Molaei, Cardiology Division, Department of Pediatrics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Received: December 08, 2021; Published: May 26, 2022

Citation: Akbar Molaei., et al. “Cardiac Findings in Childhood Syncope”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 5.6 (2022): 14-20.

Background: Various causes can lead to a transient decrease in consciousness, which can be traumatic or non-traumatic. Non-traumatic causes include syncope, seizures, and metabolic disorders. Syncope is a common problem in children. The aim of the present study was cardiac findings in patients with syncope referred to a pediatric clinic.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study of children who referred to the clinic of Tabriz Children's Hospital with at least one episode of syncope. Patients data including number of syncope events, factors leading to syncope (including prolonged standing, hyperventilation, mental stress, exercise, and prolonged starvation); Any aura before syncope (including confusion, palpitation, decreased vision, nausea, sweating, and paleness); Patient medications and family history (including syncope, sudden death, and cardiovascular disease) were recorded. The patient's clinical examination information including heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the supine and sitting position (after standing for 2 minutes) was recorded. Cardiopulmonary findings were recorded. 12-lead electrocardiography was performed for patients and information including heart rhythm, heart rate, P wave voltage, QRS length, heart axis and QTc were recorded. If there is a positive electrocardiographic or clinical result, 2D Doppler echocardiography was performed for patients and the results were recorded.

Findings: In this cross-sectional study, 100 children who referred to the clinic of Tabriz Children's Hospital with at least one episode of syncope were enrolled. The mean age of the children was 8.54 ± 2.70 years ranging from 2.5 to 16 years. The average number of syncope episodes at the time of study was 4 syncope with a range between 1 and 12 syncope. In terms of gender distribution, 44 children (44%) were boys and 56 children (56%) were girls. The family history of syncope was positive in 7 children (7%). The most common cause of syncope in children studied was syncope following exercise (33%). The most common aura was palpitation with a frequency of 29%. In the studied children, abnormal ECG was observed in 11 children (11%). Abnormalities included prolonged QTc in 4 cases, ventricular hypertrophy based on high voltage in 2 cases, atrial enlargement in 2 cases, abnormal axis in 1 case, complete heart block in 1 case, and supraventricular tachycardia in 1 case.

Conclusion: The use of an appropriate history and clinical examination along with ECG is of great value in the diagnosis of syncope with cardiovascular causes in children. It is also best to have echocardiography instead of echocardiography for all patients who are suspected and have an abnormal ECG. It was also observed in this study that the main defaults of cardiac syncope include early syncope with common periods, abnormal ECGs, and higher sitting and standing blood pressure differences.

Keywords: Syncope; Vasovagal Disorder; Children; Mortality; Cardiac Syncope.

Various causes can lead to a transient decrease in consciousness, which can be traumatic or non-traumatic. Non-traumatic causes include syncope, seizures, and metabolic disorders. Syncope is a common problem in children and defined as a sudden loss of consciousness and inability to maintain a person’s postural tone, which is usually due to dysfunction and a decrease in diffuse, temporary, and sudden cerebral blood flow [1,2]. This condition usually resolves on its own and does not leave brain sequels. The event usually begins with a series of pre-existing symptoms such as nausea, epigastric pain, lightheadedness, and paleness that lasts from a few seconds to two minutes, which can be the same or different in each attack [3]. The minimum blood flow required for normal brain activity is estimated at about 60 ml per minute for every 100 grams of brain tissue. Syncope occurs following cerebral hypoperfusion in a very short time (about 12 seconds) [4]. Syncope is divided into three main groups: NMS-mediated syncope (NMS), cardiovascular syncope and non-cardiovascular syncope. NMS or vasovagal syncope is the most common cause of syncope in young patients [5]. The mechanism of this type of syncope seems to be related to increased beta-adrenergic sensitivity of baroreceptors in the arteries and mechanoreceptors in the left ventricle after changes in body tone, circulating volume, or direct release of catecholamines from brain centers [6].

The incidence of syncope at all ages has been reported to be about 3% of total life expectancy. Syncope is more common in females and is most common between the ages of 15 and 19 [7]. According to literature, the incidence of syncope under the age of 18 is about 15%. Some studies have also reported a higher prevalence of syncope in adults, most of whom have had at least one seizure before the age of 18 [8]. In the community, the annual number of syncope episodes were between 18.1 and 39.7 per 1000 patients, which has almost the same incidence between the two genders [9]. The first reported incidence of syncope was 2.2 cases per 1,000 people per year [10]. In general, 3 to 5% of referrals to emergency departments are related to syncope cases, which is associated with 40% of hospitalizations for an average duration of 5.5 days. In addition, morbidity, about 35% of recurrences, 29% of physical injuries and 4.7% of major trauma have been reported in patients [11,12].

One of the main parts in the clinical examination of children with syncope is cardiovascular examination, which is the first step in electrocardiography (ECG). ECG examination should be performed on QT interval and T-wave morphology to diagnose long QT syndrome; Voltage recorded in leads to detect the possibility of ventricular hypertrophy, obstructive cardiac lesions or cardiomyopathies; Existence of WPW; Bradycardia or conduction disorders [13,14]. In cases prone to arrhythmias, 24-hour monitoring should be performed to detect VT, supraventricular tachycardia, bradycardia, WPW, and heart blocks [15]. Due to the causes of syncope and its association with some serious cardiovascular disorders in children, evaluation of relevant findings and determination of common and uncommon findings can lead to early diagnosis and especially better management of these patients. Therefore, the aim of the present study was cardiac findings in patients with syncope referred to a pediatric clinic.

In this cross-sectional study, according to the sampling, which was a count, the minimum sample size based on the etiology variable of syncope (syncope after physical activity) with a prevalence of 27.6% based on the study of Hegazy., et al. [16], using Power software and Sample Size Considering 90% alpha power and 5% error, 100 patients were set as the minimum sample size. Then, children who had referred to the clinic of Tabriz Children’s Hospital with at least one case of syncope were examined and the following information was obtained: 1- Syncope-related factors: Patients’ information including the number of syncope events, factors leading to syncope (including prolonged standing, hyperventilation, psychological stress, exercise and long-term hunger); Any aura before syncope (including confusion, palpitation, decreased vision, nausea, sweating, and paleness); Patient medications and family history (including syncope, sudden death, and cardiovascular disease) were recorded. 2- Clinical examination of the patient: Clinical examination information of the patient including heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the supine and sitting position (after standing for 2 minutes) was recorded. Cardiopulmonary findings were recorded. 3- Electrocardiography: 12-lead electrocardiography was performed for patients and information including heart rate, heart rate, P wave height, QRS length, heart axis and QTc were recorded. 4- Echocardiography: In case of positive electrocardiography or clinical findings, 2D Doppler echocardiography was performed for patients and the results were recorded.

Inclusion criteria were existence of at least one syncope based on the definition of sudden and complete loss of consciousness, consent to participate in the study, absence of other congenital heart diseases and absence of seizures. Patients with maternal retardation and metabolic disorders were excluded.

The data obtained in the present study were analyzed by SPSS statistical analysis software version 18. Demographic information was analyzed by descriptive statistical methods and the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation and frequency (percentage) by appropriate graphs and tables. Quantitative variables were compared by Student’s t test and qualitative variables were compared by Chi-Square test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

In this cross-sectional study, 100 children who referred to the clinic of Tabriz Children’s Hospital with at least one case of syncope were studied. The mean age of the children was 8.54 ± 2.70 years ranging from 2.5 to 16 years. The average number of syncope cases at the time of study data collection was 4 syncope with a range between 1 and 12 syncope. In terms of gender distribution, 44 (44%) were boys and 56 (56%) were girls.

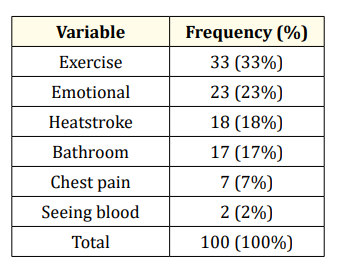

In a review of the clinical records of the children studied, 70 children (70%) had experienced syncope for the first time, while 30 children (30%) had at least one history of syncope and were chronically ill. The family history of syncope was positive in 7 children (7%). In addition, none of the children studied had a family history of cardiovascular disease and sudden death. The most common cause of syncope in children studied was exercise-related syncope, which accounted for 33% (33%). The frequency of factors leading to syncope in the studied children is shown in table 1.

Table 1: Frequency of factors leading to syncope in children studied.

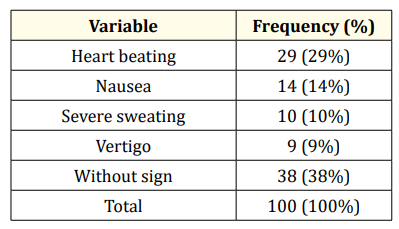

Examination of the early clinical signs of syncope (aura) in the studied children showed that the most common symptom was palpitation, which had a frequency of 29 cases (29%). The frequency of early clinical signs of syncope in children is shown in table 2. Also in 38 patients (38%) no clinical symptoms were reported at the time of syncope.

Table 2: Frequency of early clinical signs of syncope in children studied.

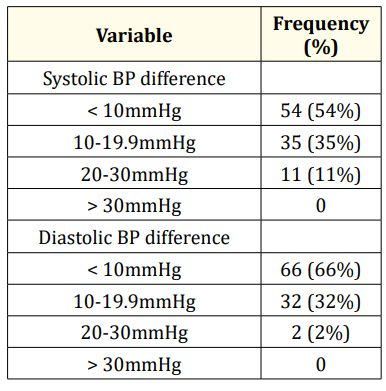

Clinical examination of patients showed that the average number of patients’ previous heart rate was 107.03 ± 17.49 beats/min with a range between 67 and 158. The mean systolic blood pressure of patients at sitting was 101.3 ± 12.4 mmHg with a range between 74 to 144 mm Hg and at standing was 105.7 ± 13.4 mmHg with a range of 77 to 145 mm Hg. The mean diastolic blood pressure of patients in the sitting area is 66.4 ± 10.5 mmHg with a range between 40 to 99 mm Hg and in standing position is 64.3 ± 9.4 mmHg with a range of 44 to 90 mm Hg. 19 patients (19%) had murmur on clinical examination. The frequency with cases of differences between systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared to two standing and sitting positions (10 minutes apart) were shown in table 3.

Table 3: Frequency of differences between systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared to standing and sitting (10 minutes apart).

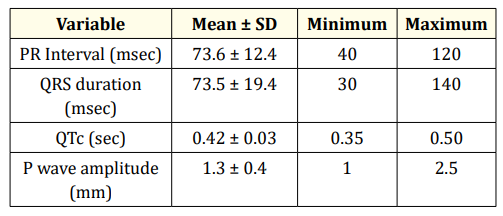

12 lead ECGs were taken from all children studied and the results are shown in table 4. In the studied children, abnormal ECG was observed in 11 children (11%). Abnormalities included prolonged QTc in 4 cases, ventricular hypertrophy based on high voltage in 2 cases, atrial enlargement in 2 cases, abnormal axis in 1 case, complete heart block in 1 case, and supraventricular tachycardia in 1 case.

Table 4: ECG evaluation results of the studied children.

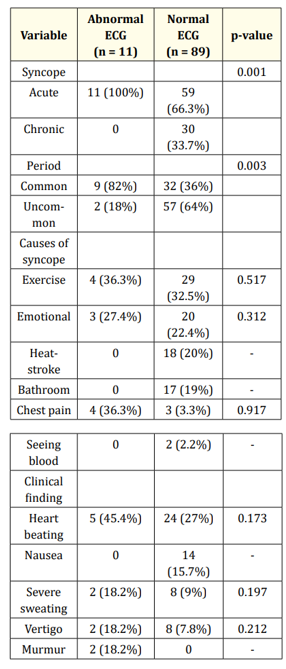

A comparison of ECG findings (normal or abnormal) with syncope-related factors is shown in table 5.

Table 5: Comparison of ECG findings with syncope-related factors.

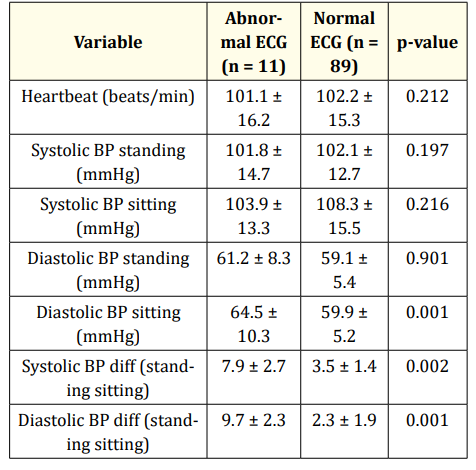

A comparison of clinical examination findings on heart rate and blood pressure based on ECG results is shown in table 6. The results showed that patients with abnormal ECG results had significantly lower diastolic blood pressure at sitting time and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure were higher than standing and sitting.

Table 6: Comparison of heart rate and blood pressure based on ECG result.

In the present study, patients who had abnormal ECG results or were suspected of having a heart disorder underwent echocardiography. A total of 24 patients underwent echocardiography, of which 4 cases (16.7%) had abnormal results. Abnormalities included one case of dilated cardiomyopathy, one case of HOCM, one case of mitral prolapse, and one case of mitral valve regurgitation. In two of these patients, the ECG result was normal, which included one case of mitral prolapse and one case of mitral valve regurgitation. It was observed that there was a significant relationship between abnormal ECG results and abnormal echocardiographic results (p = 0.001).

Syncope is a common occurrence in children and in some cases can cause concern in parents, teachers and companions. This phenomenon is one of the main reasons for frequent visits to pediatricians and emergency departments. Syncope occurs for many major reasons, including anatomical disorders of the nerves, heart, neurological, psychological, and metabolic problems [17]. Most studies agree that syncope is a common problem in the community and requires long-term health and maintenance services. The initial incidence of syncope is 2.6 per 1,000 people per year. If the incidence of syncope is considered constant over time, it is equivalent to 6% in 10 years, or 42% in the lifetime of a 70-year-old. In general, investigating the causes of syncope is one of the diagnostic and therapeutic goals of these patients, which in some cases remains unknown and is costly. On the other hand, in the majority of patients with syncope, heart problems are also mentioned in the additional evaluations in most cases. In the present study, abnormal ECG and cardiovascular causes leading to syncope were observed in 11% of patients. The findings of our study are consistent with the study of Driscoll. et al. Who reported a 10% prevalence of cardiac causes [18]. However, there are other studies that have reported lower rates of cardiac syncope, including 4.5% [19], 3.9% [20] and 2% [17]. On the other hand, in the study of Kilic., et al. This rate was reported to be 30.5% [21] and in the study of Wolff., et al. 28% [5]. Of course, one of the things that should be considered in the evaluation of cardiac causes leading to syncope in studies is the type of sampling and the center of the patient sampling location. The sampling hospital in the present study is a pediatric referral hospital in the center of the province, which seems to show a higher frequency compared to the emergency center in the incidence of cardiac causes leading to syncope. Another aspect is related to the definition of cardiac syncope. In the study by Ritter., et al. [19], patients with a diagnosis of minor valvular lesions, PDA, septal disorders, and decreased left ventricular outflow were not considered as cardiac syncope, and only patients with cardiomyopathies and electrical heart disorders were considered. In contrast to the above study, in the present study, patients were studied from all aspects and the causes were extracted. The importance of accurate history and proper clinical examination for the assessment of syncope in children has been expressed by many researchers [22,23]. However, in the present study, it was observed that the use of accurate history and clinical examination alone is not enough to determine cardiac syncope and more cases are needed, which is consistent with the results of the study by Ritter., et al. [19]. Also, children cannot properly describe what happened in terms of the type of syncope, the duration of anesthesia, and his condition. In addition, many cases of syncope have occurred in schools and therefore detailed information is not provided to the physician. In the present study, only in 2 patients with abnormal ECG, murmur was observed and unlike previous studies in the present study, no relationship was observed between the presence of murmur and cardiac syncope [17]. In our study, it was observed that patients with abnormal ECG results had lower diastolic blood pressure at sitting time and had a higher difference between standing systolic and diastolic blood pressure than standing sitting. One of the most common causes of syncope in children is neurocardiogenic syncope and these people also have an abnormal response to orthostatic stress, which confirms the above finding in the present study [17,24,25]. One of the evaluation tools for patients with syncope to diagnose cardiogenic syncope is the use of ECG, which is easy to use and inexpensive, and is also available almost everywhere. Based on previous studies, this tool has a high diagnostic and prognostic value in syncope evaluation [26]. In the present study, 11% of patients had abnormal ECG results, which was diagnostic in 2 patients who had abnormal echocardiographic findings. In fact, in the results obtained from ECG, the findings of patients’ cardiac major are fully observed and it is suggested that in all patients and children with syncope, the first ECG evaluation be performed following the occurrence of syncope [27]. Cardiac arrhythmias are one of the main and dangerous causes of syncope [5]. In the present study, some cases of arrhythmia were observed in some patients, which based on previous studies, the accurate evaluation of this issue can be well determined using a 24-hour Holter ECG. In a study by Kilic., et al. It was reported that arrhythmias were responsible for 30.5% of syncope in children [21]. Summary of the findings of the present study shows that syncope in children in both sexes is almost the same and does not depend on age. In this population, the most common cause of syncope was exercise, and it was observed that hemodynamic regulation disorders are the main factor.

According to the results obtained in this study, it can be concluded that the use of an appropriate history and clinical examination along with ECG is of great value in the diagnosis of syncope with cardiovascular causes in children. It is also best to have echocardiography for all patients who are suspected and have an abnormal ECG. It was also observed in this study that the main defaults of cardiac syncope include early syncope with common periods, abnormal ECG, and higher sitting and standing blood pressure differences.

The present study with the code (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.852) was approved by the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. All patient information was strictly confidential. No additional costs were imposed on patients.

Copyright: © 2022 Akbar Molaei., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.