Sangay Dorji1*, and Samten Wangchuk2

1 Principal, Daga Pry School, Dagana, Bhutan.

2 Principal, Minjey MSS, Lhuntse, Bhutan.

*Corresponding Author: Sangay Dorji, Principal, Daga Pry School, Dagana, Bhutan.

Received: March 15, 2022; Published: March 23, 2022

Citation: Sangay Dorji and Samten Wangchuk. “Teacher’s Workload and its Efficacy in Classroom Teaching in Primary Schools Under Punakha Dzongkhag”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 5.4 (2022): 03-14.

Teachers’ workload is associated with effective classroom teaching and learning. The academic performance of the school is determined by the amount of teachers’ workload. Primary school teachers’ workload is challenging for effective classroom teaching and learning.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to study the teachers’ workload of primary school teachers in Punakha dzongkhag. The study involved potential additional work areas that burden primary school teachers. The study employed mixed-method design. Survey questionnaires and interview were used to collect data. The target population comprised of primary school teachers and parents in Punakha dzongkhag. The entire population was 79 participants from nine primary schools and a few Extended Classrooms (ECRs). Out of 79 participants, 30% was taken for random sampling. Five teachers were selected from primary schools and one teacher from Extended Classroom for the interview. Mixed gender was selected for the interview. Ten parents were interviewed from different primary schools. Quantitative and qualitative data were presented separately and analyzed. The data triangulation was done in the findings and discussions.

The study findings showed that teachers’ over workload has a negative impact on classroom teaching and learning due to limited time for lesson planning and tasks assessment. Teachers in primary schools had to devote certain time doing non-academic activities. Study found that even among the primary schools, teachers working in schools with less than 100 students had to shoulder more responsibilities. In smaller primary schools, staffing pattern is different whereby certain support staff are not entitled. Therefore, the researcher recommends Ministry of Education to reconsider pupil-teacher ratio and relook into the staffing pattern in primary schools. Primary school teachers need to specialize in a maximum of two subjects to enhance effective classroom teaching.

Keywords: Responsibilities; Monitoring; workload, Assessment and Multi-grade Teaching.

ECR; NAPE; NBIP; PER; CBA

Teachers are considered the key source providing academic and lifelong education to students. Teachers play a key role in schools for enhancing academic excellence and lifelong learning of students (The Bhutanese School Management Guidelines and Instructions, 2005) [1]. They are expected to deliver effective classroom teaching with contemporary pedagogies and skills. However, for an effective teacher, Susan (2006) states that teachers must have a conducive working environment [2].

Thus, effective classroom teaching is not only determined by teacher’s effort but also by how much work is assigned to them.

Teachers’ working environment is further described by Susan (2006, p.2) as “the organizational structures that define teachers’ formal positions as a leader with others in the school, such as lines of authority, workload, autonomy and supervisory arrangements” [3]. Besides, the study focuses on resources, workloads and professional support in primary education.

The working environment is a priority for Bhutanese primary teachers, because it may increase teachers’ inspiration to teach young and innocent learners. As remarked by Rhodes (2014) all teachers have the possibility of reaching their potential as an educator with the right professional development, supportive working environment, and meaningful feedback [4]. Further, Rhodes states that teachers’ working environment plays an important role to students as teachers can give attention to students (2014)[4,5]. Bhutanese primary teachers experienced minimal professional support, instructional and human resources. This is apparent from the primary education programme at the ECR(s), community schools and multi-grade teaching schools. In such teaching, environment affects students’ academic performance. The National Education Framework (2012, p.34) reports that “the main challenge facing the education sector was to enhance the proportion of pupils achieving the expected learning outcomes specified for different stages of school education” [6]. Thus, this study is focused on primary school teachers’ working environment and its effect on classroom teaching and learning.

Teachers’ working environment becomes more comfortable in presence of adequate resources both instructional and human. This will confirm effective classroom teaching and learning, especially children in disadvantaged communities and in lower grades. Similarly, the presence of positive school culture like collaboration within teachers and principal to support each other in professional and personal needs would promote a better working environment.

The workload for Bhutanese primary school teachers is heavy. Human resources like teaching and non-teaching staff in primary schools are inadequate. The inadequacy of staff is either controlled by the Ministry’s policy or improper teacher deployment method.

Teachers are not willing to work in an environment where they would have to shoulder multiple responsibilities. It demotivates teachers in the teaching profession and develops a feeling of low inspiration in their job. Teachers feel that teaching profession is a stressful job because of over workload and inadequate instructional time. According to Greenwood and Simpson (2010, p.1), “teachers around the world are asked to do many things in the course of their job” [7]. It is no different in Bhutan. Teachers in primary schools had to commit to both instructional and non-instructional responsibilities. This may result in ineffective classroom teaching and learning.

It is seen that ECR and Community Schools are managed by a teacher. Thus, Zangmo (2016) stated that ECR and Community Schools are with one teacher teaching all the subjects [8]. It is observed that teachers have limited time to assess students’ tasks and prepare lesson plans for effective classroom teaching and learning.

What is the teaching workload of Bhutanese primary school teachers?.

Sub-questions

According to Creswell (2011), it focuses on collecting, analyzing, and mixing both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study or series of studies [9]. Its central premise is the use of quantitative and qualitative approaches. Combination of two methods provides a better understanding of the topic.

There are certain reasons to employ a mixed approach in the study. Rossman and Wilson (1985) identified three reasons for combining quantitative and qualitative research [10]. The combinations are used to enable confirmation or corroboration, develop analysis to provide richer data and initiate new modes of thinking by attending to paradoxes that emerge from the two data sources.

The phenomenological study, the researchers “describe the meaning for several individuals of their lived experiences of a concept or a phenomenon” (Creswell, 2007, p.58) [11]. This study states that participants may be located at a single site but most important participants must be individuals who have all experienced the phenomenon being explored and can articulate their experiences. Creswell (2007) states that the more diverse the characteristics of the individuals, the more difficult it will be for the researcher to find common experience, theme, and overall essence of the experience [9,12]. In order to avoid those problems, this study included only selected primary schools, community and extended classroom (ECRs) in Punakha dzongkhag.

The researcher has chosen Punakha dzongkhag primary schools to collect data. For this study, the researcher had selected different schools looking at different aspects in terms of location from the dzongkhag headquarter, class level, and school size.

Participants selected were primary school teachers and parents from different locations, extended classroom and community schools within Punakha dzongkhag. To study the teachers’ workload in government primary schools, five teacher participants and parents from four primary schools, and one participant from the extended classroom (ECR) and community schools were selected for interviews. Survey data was collected from eight primary schools and seven extended classrooms (ECRs) which made up the sample size of 89 participants.

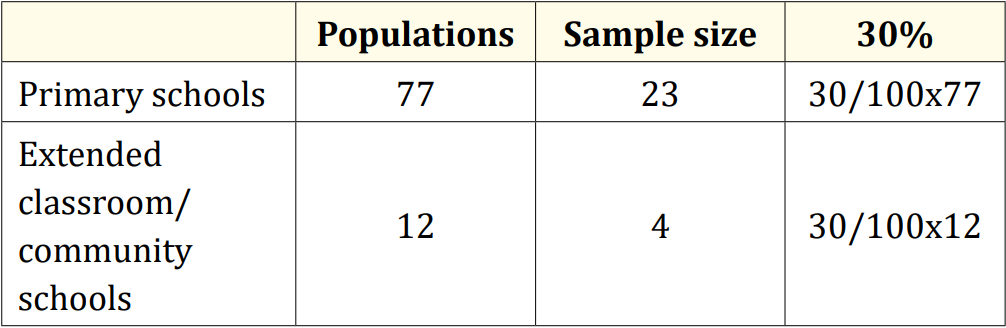

Fraenkel and Wallen (1996), Gravy (1990), Babbie (1992) and Evy (1972) (cited in Omayio, 2013) recommended that the sample size should form 30% of the population for the research findings to be generalized (see table) [13]. The random sample size taken was 30% of the entire population of 89 from primary schools.

Table a

The considerations for selection of participants were teachers who served at least one year in the present school. A teacher with a minimum of three years teaching experiences was selected. National Contract Teachers and non-regular teachers were not selected as study participants. Teacher-participants from primary schools, ECR(s) and Community schools were involved in the study. Further, for better reliability and accuracy in terms of data collection, mixed genders participants were selected.

In this method, data collection steps include setting the boundaries for the study. According to Creswell (2007), information is collected through unstructured or semi-structured interviews, observations, documents, and visual materials [9,12,14]. In this study, semi-structured interview method was used for data collection. At the time of gathering data, a detailed interview was conducted.

According to Babbies (cited in Creswell, 2009), survey research is a study of numeric descriptions of trends, attitude, beliefs and opinions of populations by studying a sample of that population [15]. Survey structured questionnaire tool was administered to primary schools teachers and principals under Punakha dzongkhag.

The study used concurrent approach by collecting both quantitative and qualitative data concurrently. The survey questionnaire is based on Likert scale. The data was collected using survey questionnaire using a Likert scale format; 1 strongly disagree (SD), 2 disagree (D), 3 neither disagree nor agree (NDA), 4 agree (A), strongly agree (SA), and 5 not applicable (NA). In this study, face to face interview was conducted besides administering survey questionnaire. The interviews were tape-recorded and later transcribed.

Data collected through both qualitative and quantitative methods were presented separately and further analyzed by comparing both the data findings. According to Creswell (2003) data analysis involves making sense out of text and image data [16]. Glesne (1999), states that data analysis involves “organizing what you have seen, heard or read so that you can make sense of what you have learned” [17].

The interview data were analyzed using Creswell’s (2003) generic steps for analyzing data [9,12,14,16,18]. Data were organized and prepared for analysis after transcribing into notes from the interviews. Data were read in order to obtain a general sense of information and to reflect on its overall meaning. Detail analysis was carried out with coding process and derived descriptions involving detail rendering of information about people, places, and events in the setting.

The data collected from the field were analyzed by recording and computing in the statistical computer program EXCEL. The data were computed in the form of frequency, table, and graphs.

Before commencement of data collection, the researcher sought written approval from the District Education office, Punakha (Appendix B). Data collection leave permission was sought from the Principal Logodama Primary School (Appendix C). Finally, all selected school Principals’ permission seeking letter and participants’ consent form was developed. Consent forms were developed incorporating points suggested by Creswell (2003); A) the right to participate voluntarily and also to withdraw at any point of the interview, B) the purpose of the study was made known to the participants. C) Before the interview, signature of participants was collected in the consent form.

Participants were made free to choose a place where they may feel comfortable. The interview session was made informal. Participants were assured that their identity will not be disclosed. Throughout the research, confidentiality was maintained with regard to any information that might cause problems. Participants’ views were respected. If they were uncomfortable with the interview questions, they were given the option to withdraw from the interview. Participants were also given the right to leave any questions without responding. Interviews were conducted in a safe place during free periods.

After the interview, any information provided through the transcribed interview was kept secure and made available only to the persons concerned. All the documents will be destroyed after the exceeding validation period of five years. Any statement participants thought was sensitive was deleted. Participants were assured that their names would not be reflected at any case in the study.

Data display organized, compressed and assembled information. There are many different ways of displaying data in graphs, charts, networks, diagrams of different types. Any appropriate ways were used in the data analysis to draw and verify conclusions.

The study presents survey questionnaire on seven themes. The survey questionnaires were administered to 30% of the sample of 79 teachers from primary schools and seven extended classrooms ECR(s) under Punakha dzongkhag. Quantitative data were triangulated with qualitative data gathered through interviews.

The survey questionnaire theme on teachers’ workload was sought to find primary school teachers’ workload under Punakha dzongkhag. This theme was further divided into eight different sub-variables. The sub-variables are presented in separate graphs.

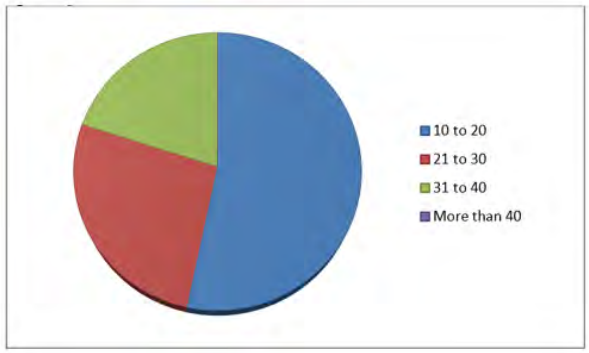

The variable on class strength was formulated to find the maximum number of students in a class that teachers taught in primary schools under this dzongkhag (see figure 1).

The data showed that 53% of the primary teachers under this dzongkhag had class strength of 10 to 20 students. Teachers having class strength of 21to 30 students was 27%. Teachers who had the class strength of 31 to 40 students was 20% and none of the teachers had more than 40 students in the class.

Figure 1

By looking at the findings, the maximum number of Primary Schools under Punakha dzongkhag had class strength of 10 to 20 students. As per the finding, primary school teachers in the dzongkhag had comfortable class size. Based on the study finding, effective classroom teaching and learning occurred in primary schools. Class size is one of the factors for effective classroom teaching. When there is less number of students in a class, more 07 The different scores of each scale on a number of different sections taught by teachers were shown in percent. The study showed that primary school teachers who taught two different sections was 40% while 39% of teachers taught three different sections. Teachers who taught four different sections was 7%. Teachers who taught more than five different sections was 14%.

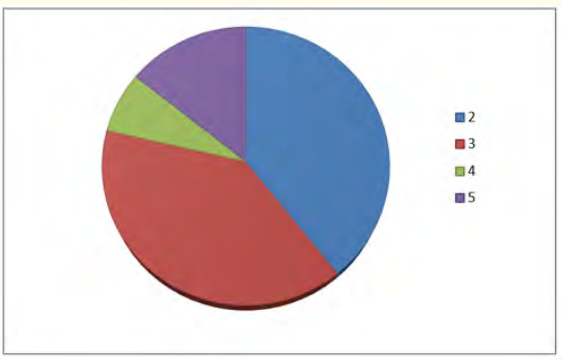

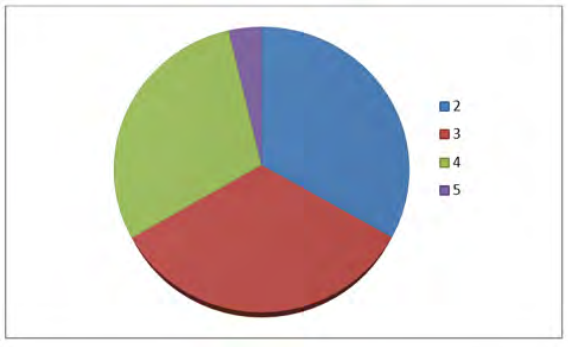

This sub-variable was to find the number of sections teachers taught daily and workload of the teacher in the school (see figure 2).

Figure 2

The different scores of each scale on a number of different sections taught by teachers were shown in percent. The study showed that primary school teachers who taught two different sections was 40% while 39% of teachers taught three different sections. Teachers who taught four different sections was 7%. Teachers who taught more than five different sections was 14%.

The findings showed that maximum number of Primary School teachers taught two to three different sections. Teachers who taught two different sections and three different sections had a negligible difference of 1%. However, there are school situations where teachers had to teach five different sections, as findings showed 14%. Teachers teaching four to five subjects daily would compromise the quality of teaching. Teaching requires sufficient time for lesson planning and preparation. Teachers need a manageable number of sections to assess students’ tasks. Fewer students to handle, more effective teacher can teach students.

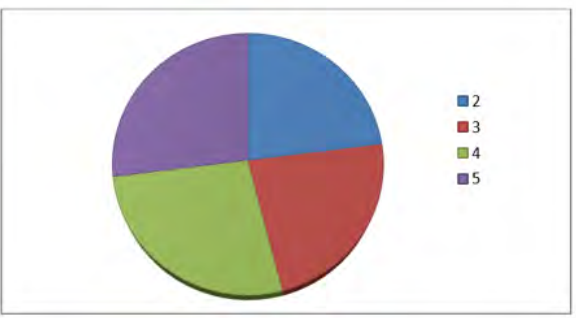

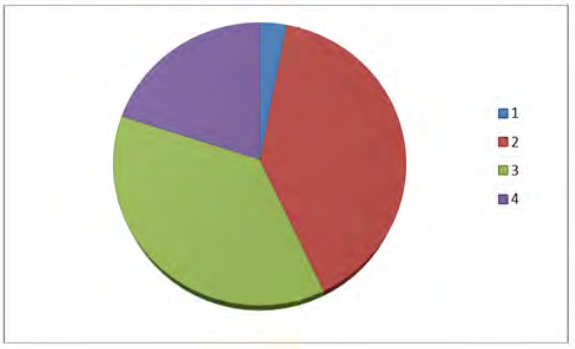

The variable on non-teaching responsibilities of teachers was sought to find the number of non-academic responsibilities of primary school teachers besides academic responsibilities under Punakha dzongkhag (see figure 3).

Figure 3

A range of scales was formulated to find primary school teachers’ non-academic responsibilities. Teachers having two non-teaching responsibilities was 23% and with same percentage of teachers having three non-teaching responsibilities. Teachers having four non-teaching responsibilities was 27%. Teachers having more than five non-teaching responsibilities was also 27%.

By looking at the findings, the majority of primary school teachers under Punakha dzongkhag were overloaded due to non-teaching responsibilities in the school. Maximum number of teachers had four to five non-teaching responsibilities besides their regular academic responsibilities. Non-academic responsibilities are equally important as academic responsibilities in the school. However, it compromises effective classroom teaching and learning because of losing focus on the main task.

The variable on different subjects teachers taught was sought to find the number of different subjects taught by primary school teachers under this Dzongkhag.

Figure 4

The study participants responded within four different ranges of scales on subjects taught by teachers. Teachers teaching two different subjects was 33% while 30% of the teachers taught three different subjects. The data showed 30% of teachers taught four different subjects. Primary school teachers in this dzongkhag who taught five different subjects was 4%.

Looking at the data presentation, majority of teachers taught three to four different subjects daily. A teacher teaching three to four different subjects daily would pose a challenge to planning for all the subjects. Classroom teaching without proper planning and preparation cannot result in effective teaching and learning. In order to achieve desired learning outcome, an adequate amount of time is required for proper lesson planning and preparation.

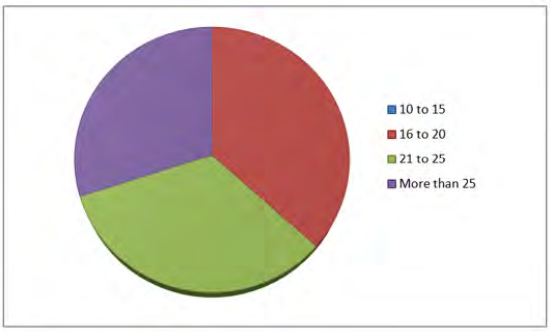

The variable on teachers’ teaching hours in a week was sought to find out the total classroom teaching hours in a week of primary school teachers under Punakha dzongkhag (see figure 5).

Figure 5

This variable was formulated to find out the Primary School teachers’ teaching hours in a week. Participants teaching 16 to 20 hours in a week was 37%. Teachers teaching 21 to 25 hours in a week was 33% and teachers who taught more than 25 hours in a week was 30% in the survey study.

Looking at the findings, Primary School teachers were teaching 16 to 20 hours in a week. The other two scales 20 to 25 hours and more than 25 hours in a week were almost equal. Looking at each score, on an average teachers work 20 to 25 hours particularly in teaching in a week. Primary school teachers were teaching as per the mandated teaching hours of the Education Ministry.

The variable on the preparation of daily lesson plan was sought to find out the number of lesson plans prepared daily by primary teachers in the school (see figure 6).

Figure 6

Four different scales were prepared to find out the number of lesson plans prepared daily by primary school teachers. 3% of the teachers prepared one lesson plan, while teachers who prepared two lesson plans daily was 40%.Teachers who prepared three lesson plans daily was 37% and teachers who prepared four lesson plans daily was 20%.

The findings showed that on an average Primary School teachers prepared two to three detailed lesson plans daily. By looking at the lesson plan preparation of 55 minutes duration, teachers spent at least one to two hours daily. The effectiveness of classroom teaching would significantly depend on how teachers get adequate time to prepare their lesson plans. Lesson plan guides teachers for effective classroom teaching and learning.

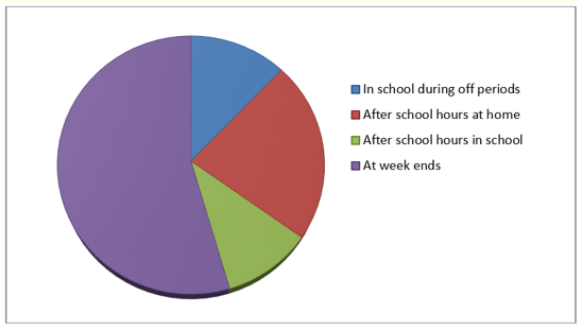

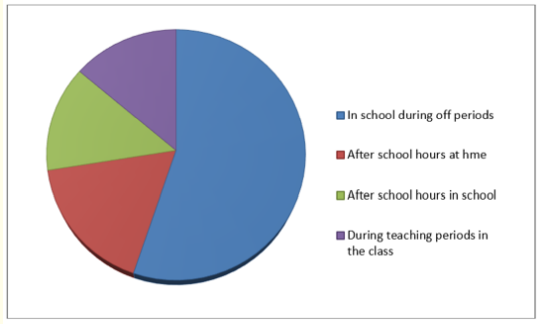

The variable on lesson plan preparation time of teachers was sought to find out when teachers prepare lesson plans (see figure 7).

Figure 7

The researcher prepared four different possible time teachers usually used to prepare their lesson plans. Teachers who prepared lesson plans in school during off periods was 12%. Teachers who prepared lesson plans after school hours at home was 23%. Teachers who prepared lesson plans after school hours in school was 11%. Teachers who prepared lesson plans on weekends was 54% in this study.

By looking at the findings, primary school teachers under Punakha dzongkhag had limited time to prepare lesson plans during school hours. The highest data showed that 54% of the teachers prepared lesson plans during weekends at home. The Primary School teachers in Punakha dzongkhag were engaged throughout the week doing school’s work.

The variable on teachers’ time to assess students’ work was sought to find out when teachers assessed students’ task (see figure 8).

Figure 8

To find Primary School teachers’ time to assess students’ task, the researcher formulated four different possible times that teachers usually assessed students’ tasks. Teachers who assessed students’ work in school during off periods was 55%. Teachers who assessed after school hours at home was 17%. Teachers who assessed students’ work after school hours in the school was 14%. Participants who assessed students’ task during teaching periods in the class was 14%.

Looking at the findings, maximum number of teachers assessed students’ task during off periods in the school. However, teachers in primary schools got minimum periods for planning and students’ task assessment. Teachers had to teach three to four different subjects. It is learned that teachers had no sufficient time for quality assessment. Quality students’ task assessment is an effective classroom teaching and learning process.

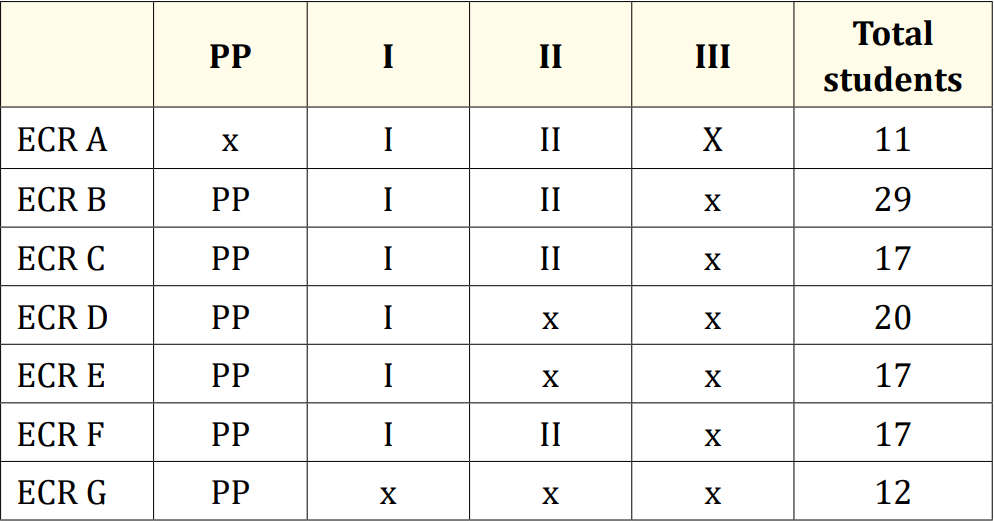

The variable on the workload of extended classroom teachers was sought to find out the teachers’ working environment in ECR in Punakha dzongkhag. There were seven ECR(s) in total in the dzongkhag (see table 1).

Table 1

The findings showed the working scenario of 7 ECRs under Punakha dzongkhag. The maximum number of students was in ECR B with 29 students. The minimum number of students was in ECR A with 11 students. By looking at the class size, it was comfortable in classroom teaching but teacher(s) had to teach six to nine different subjects daily. Except for ECR A, all other ECRs had class PP where this class had to be taught separately, as mandated by the policy. Besides classroom teaching, ECR teacher(s) had to do other non-teaching work in the school.

The researcher presents interview data from teachers and students of primary schools. The interview data were transcribed and coded under different themes. Participants and schools are coded under different codes. Teacher participants as ‘T’ (Teacher=T), schools as ‘S’ (School=S) and students as ‘SS’ (Students=SS). The interview data analysis was used in the survey data findings for comparison of two data. The study followed colour coding, memoing and developing a proposition for data analysis.

The research question was formulated to find out the perspectives on teachers’ workload in the school and its effect on classroom teaching and learning. There were common perspectives shared on the teachers’ workload in the school.

The participants described workload of teachers as an important aspect of students’ academic achievement. The participants expressed that it was important for teachers to be assigned with less responsibilities, especially non-teaching roles for effective classroom teaching and learning. It was understood that over workload is the source of developing stress and inefficiency of a person. Primary School teachers in the dzongkhag had a heavy workload. Multiple responsibilities of teachers added workload. The teacher interviewee responded, “teachers’ working environment in our school, we have a heavy workload. We have no enough time for proper lesson planning and preparation” (Int. T1 24/2/2021). It was learnt that teachers’ working environment in the dzongkhag had a heavy workload.

Further, to study in detail, the researcher inquired specific questions on teachers’ workload and its effect on classroom teaching and learning.

The question on human resources was formulated to find out the human resources conditions and its effect on classroom teaching and learning. It was learnt that adequate teachers and other supporting staff are crucial in achieving the school goals. Participants expressed the importance of adequate human resources in the school. Adequate human resources help to achieve better academic performance in the school. The participants pointed out the lack of non- teaching staff and their challenges in the school. The researcher learnt that non-teaching staff is deployed based on the number of students in the school. Primary schools with less than hundred students is eligible for only school caretaker. However, the participants suggested that it is important to deploy Health and Physical Education (HPE) instructor, librarian and store in-charge in the school. It was learned that teachers spent instructional hours doing non-teaching activities. Non-teaching staff in primary schools in the dzongkhag was only school caretaker at the time of conducting the study. Teachers’ instructional hours are shared doing non-instructional responsibilities. Teachers’ focus on classroom teaching is lost in the process of doing multiple tasks” (Int.T1 24/02/2021).

The primary school teachers had to teach all curriculum with little experiences. It is found necessary to focus on maximum two subjects. Teachers teaching all subjects affect the quality of classroom teaching and learning. Schools face the challenge of having competent and experienced subject teacher. Primary Schools in the dzongkhag lack Dzongkha (national language) teachers. The interview participants shared the situation of Dzongkha language teacher shortage in the school. The participant said:

As per the policy, Dzongkha (national language) subject has to be taught by Dzongkha teachers. At present we have only two Dzongkha teachers with nine sections. All sections cannot be taught by two Dzongkha teachers, other general teachers have to share Dzongkha subject. It affects content delivery to the learners. (Int.T3 24/02/2021).

General teachers were asked to teach Dzongkha subject in the school. The subject content delivered by general teachers differ from Dzongkha teachers. The instructional quality is compromised in the Dzongkha subject.

The study informed that Primary School teachers’ experienced heavy teaching workload following pupil-teacher ratio deployment. Instead, participants suggested deploying teachers based on number of sections and subjects in the school. This can address subject teacher shortage and teaching workload in primary schools. An interviewee shared:

We have seven teachers and eighty four students. As per pupilteacher ratio, it seems that we have excess teachers. But, the level of class ranges from class PP to VI, seven teachers are not enough. We have to look into the number of subjects to teach. (Int.T4 25/02/2021).

Looking at the responses, Primary schools require non-teaching staff to share non- teaching responsibilities, particularly in-charges. Primary teachers’ teaching hours were divided doing non-teaching responsibilities. According to the existing teacher deployment policy, Primary Schools in the dzongkhag had sufficient teachers, however, in reality the study found an acute shortage of Dzongkha teachers. General teachers faced difficulties in teaching Dzongkha subject.

The study revealed that primary teachers were asked to carry multiple responsibilities in the school. A multiple of tasks diverts the focus from classroom teaching. The interviewee shared, “I am library in-charge; games and sports coordinator, club coordinator, house master, literary in-charge and cultural coordinator. Besides teaching, other non-teaching responsibilities disturb classroom teaching” (Int.T4 25/02/2021). It was found that a teacher with multiple tasks develops anxiety. Eventually, the quality of classroom teaching is compromised.

Primary School teachers in the dzongkhag taught five to six different subjects daily. The participant responded that “teachers in our school have a heavy workload. This year we have minimum five different subjects to be taught by a teacher daily. We are not able to prepare lesson plans for all the subjects taught” (Int.T1 24/02/2021). Teachers teaching more subjects have more plans to prepare and more students’ task assessment. Classroom teaching without proper lesson planning cannot be considered effective teaching and learning.

The study participants informed that Primary School teachers taught 25 periods of 55 minutes in a week. The participants expressed that over workload leads to mental stress and frustration in the teaching profession. A study participant shared:

If a teacher is overloaded with the school responsibilities, there are some problems at home. Then it is the devastation for the teacher. If a teacher is not happy at home, he brings problem in school. So, this affects whole teaching-learning processes in the school. (Int.T4 25/02/2021).

On the other hand, participants agreed that doing multiple tasks was an opportunity to gain administrative work experiences. The interviewee responded to the question that “we gain more experiences doing more responsibilities. Teachers are exposed to work experiences such as school self-assessment (SSA) and school improvement plan (SIP) planning” (Int.T1 24/02/2021). The other interviewee agreed the same that “…but I do not feel this because I love doing this and it is the source of experience” (Int. T3 24/02/2021). However, teachers’ over workload has no positive impact on classroom teaching and learning.

Based on the interview responses, primary school teachers were overloaded. Teachers had to teach four to five different subjects every day. Moreover, teachers had non-teaching responsibilities to perform in the school. Participants expressed a feeling of anxiety due to over workload in school. Teachers under heavy work pressure impinged on classroom teaching.

Teachers are deployed based on the pupil-teacher ratio policy. It is the common method to deploy teachers in schools. The present pupil-teacher ratio in the Bhutanese Education System is 1:25. The participants expressed the challenges associated with pupil-teacher ratio deployment policy as it leads to teachers being overburdened in the school. It was learnt that teachers were deployed based on a number of students in the school. The participants said that the present teacher deployment policy added to teachers’ workload. It has also been learnt that the problem associated with high pupil-teacher ratio adds to teaching workload. The participants explained that primary schools with classes ranging from PP to VI had minimum seven sections. There are 27 subjects to teach. A participant further responded:

I am teaching four subjects. The number of students is only 40. If you follow pupil-teacher ratio, it is not a big problem to teach. But, when it comes to real ground, a teacher teaching four different subjects is challenging to provide quality teaching. (Int. T4 25/02/2021).

The participants responded that the high pupil-teacher ratio added to the workload of teachers in primary school. It was also felt that teachers’ over workload compromised the quality of classroom teaching and learning. A teacher interviewee explained:

The pupil-teacher ratio policy may be feasible in a higher level of schools. It does not work in primary schools. Sometimes in a school, we have 60 students in seven sections. There are 27 subjects to be taught. According to pupil-teacher ratio, the school gets two teachers. The workload of the teacher is heavy in such situation. (Int.T3 24/02/2021).

Looking at the findings, Primary teachers in the dzongkhag had heavy teaching workload. Teachers compromised the quality lesson planning and students’ tasks assessments. Proper lesson planning and preparations are most important for effective classroom teaching and learning.

Multi-grade teaching approach added to the workload of Primary School teachers. All Extended Classrooms (ECRs) and Community Schools adopted the multi-grade approach. The majority of study participants responded that multi-grade approach is challenging in Bhutanese school system. Participants said that multi-grade was a method to solve teacher shortage in remote schools. However, the objective of multi-grade approach can be different. An Interviewee responded, “Since a teacher can teach different grades in a single classroom, it helps to solve teacher shortage. But, quality of classroom teaching is compromised” (Int. T2 24/02/2021). According to interview participants, multi-grade teachers were not well trained. Teachers failed to teach effectively when different grades were combined together. This finding coincides with Yangzom (1994, cited in Royal Education Council Annual Report, 2016) which states that “there was a short supply of trained multigrade teachers throughout Bhutan”.

Participants responded that multi-grade approach is not feasible in the Bhutanese Primary schools. It is merely an addition to teachers’ workload. Student participant responded, “This teachinglearning system is a problem for us. When we are in one class there are lots of disturbances. For example, when a teacher teaches one class, the other class disturbs” (Int.S1 24/02/2021). It was also learnt that multi-grade approach added workload of teachers and caused inefficiency in classroom teaching and learning.

Looking at responses from the field interviewees, multi-grade approach involved challenges such as lack of trained teachers, heavy planning and preparation and lack of facilities for effective teaching. According to Yangzom (2016), “Effective multi-grade teaching requires trained and motivated teachers, access to… learning materials, and a stimulating environment.” Thus, teachers teaching multi-grade classes without adequate ideas and skills hinder classroom teaching and learning.

The study on teachers’ workload was sought to find out Primary school teachers’ workload, both teaching and non-teaching responsibilities. The main question includes sub-variables such as (1) number of students in a class (2) number of different sections teacher taught (3) different subjects teacher taught daily (4) total hours teacher taught in a week (5) number of lesson plans prepared daily (6) teacher’s lesson preparation time and (7) time spent by teachers on students’ work assessment.

The Primary school teachers had a minimum of four to five non-academic responsibilities apart from classroom teaching responsibilities. The total teaching hours in a week for a teacher showed the highest score of 20 to 25 hours. From these findings, it can be concluded that Primary teachers had to teach a minimum of five periods every day. By looking at academic and non- academic responsibilities of primary teachers, the teachers were overloaded. In light of the study participants’ responses, it can be strongly stated that teachers had more non-teaching responsibilities that can certainly lead to low students’ academic performance. The subvariable on lesson plans preparation time showed that 54% of the participants prepared their lesson plans during weekends. 23% of teachers prepared lesson plan after school hours. Primary school teachers had no leisure time for recreational activities. The tight schedule and hectic life added a feeling of stress and frustration towards the teaching profession. Teachers in frustrated mind cannot teach effectively in the class.

The interview question on teachers’ workload was employed to study detailed situation in primary schools. Interview participants shared a number of responsibilities that they had to perform in the school. A study participant shared, “I am library in-charge; games and sports coordinator, club coordinator, house master literary coordinator and cultural coordinator. Besides teaching duties, I have to do non-teaching responsibilities in the school” (Int. T4 25/02/2021). In addition, participants expressed the impact of over workload like stress and frustration in the teaching profession. Teachers experiencing stress and frustration because of unfavorable working conditions has huge negative impact on student’s academic performance. In this regard, a wide range of studies suggests that pupils of teachers with high job satisfaction and lower stress are more likely to perform better academically than their peers whose teachers are not able to sustain their commitment. Participants expressed that they were stressed due to heavy teaching work as well as non- teaching responsibilities.

The extended classroom (ECR) findings showed that every ECR in Punakha dzongkhag had Pre-primary (PP) class, except for one ECR. The Ministry of Education (MoE) policy states that PP class should be taught in mono grade system. However, ECR had to combine class PP with class I and II since there was only one teacher. In this situation, the teacher had to refer nine different manuals and textbooks. Effective classroom teaching cannot be expected in such an environment. Pre-primary (PP) students are new to formal schooling system and subjects such as English and Mathematics are taught in a foreign language. Classes I to II students may find same difficulties when taught in multi-grade approach. It coincides with what one of the student interviewees of multi-grade approach school said; “multi-grade teaching-learning system is a problem for us. When we are in one class there are lots of disturbances. For example, when a teacher teaches one class, the other class disturbs. That way we are not able to understand well. So, mono-grade teaching will be much better” (Int.S124/2/2021). Therefore, the study showed that teachers’ over workload impact classroom teaching.

On the basis of findings and in light of the literature on the study conducted, it can be concluded that teachers’ workload has a huge effect on classroom teaching and learning, especially for primary school children. An adequate teaching staff is a key factor to commit in pursuit of achieving quality education.

The findings showed sufficient evidence to conclude that teachers’ workload becomes relaxed when adequate human resources are in place in the school. It reduces the workload of teachers and helps effective classroom teaching and learning. The participants responded that primary schools require sufficient teachers as well as support staff. The staffing pattern reform for primary schools need immediate attention, otherwise it may hamper the quality of education due to heavy teachers’ workload of primary teachers. If possible, the Ministry needs to reconsider the existing human resource policy to further reduce the pupilteacher ratio. Primary school teachers in Punakha dzongkhag had an excess workload. Teachers had to teach three to four subjects besides multiple non-instructional responsibilities. They had little time for personal work because lesson planning and students’ tasks assessments were done at home. Teachers expressed a feeling of frustrations and stress in the teaching profession.

Copyright: © 2021 Sangita D Kamath., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.