Saima Pirzada, Zahid Anwar*, Fouzia Ishaq, Muhammad Azhar Farooq, Nazia Iqbal, Rafia Gul and Fatimah Noor

Department of Paediatrics, Fatima Memorial Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

*Corresponding Author: Zahid Anwar, Department of Paediatrics, Fatima Memorial Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan.

Received: October 25, 2021; Published: November 17, 2021

Citation: Zahid Anwar., et al. “Cord Care Practices in Newborns - Fresh Look into Old Problem”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 4.12 (2021): 26-30.

Background: Safe cord care practices in newborns reduce neonatal infections and deaths. We conducted this study to document the frequency of different cord care practices.

Methods: It was a questionnaire-based study done over 6 months in 3 tertiary care hospital of Lahore namely Fatima Memorial Hospital, Mayo Hospital and Sir Ganga Ram Hospital. Doctors interviewed mothers and female attendants of the newborns during rounds and neonatal OPD visits. The answers recorded data about socio-demographic characteristics and cord care practices.

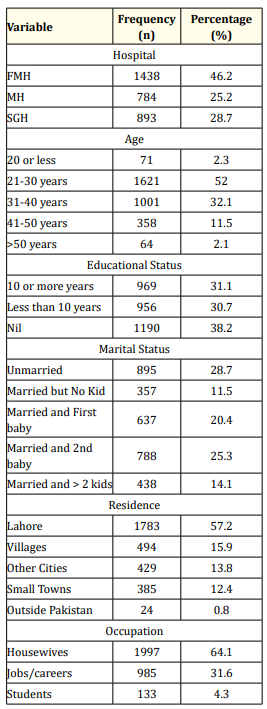

Result: A total of 3115 females participated. Mean age was 32.08 + 8.1 years. Around 38.2% (1190) were illiterate. Most (178357.2%) resided in Lahore, and only 879 (28.3%) had rural background. Most (2220-86.1%) were married. Only 1226 (39.4%) had prior experience of taking care of their own child and remaining 60.6% (1889 = unmarried + married but no kid + married and first baby) answered according to the observed or tutored family practices. Majority (1997-64.1%) were housewives.

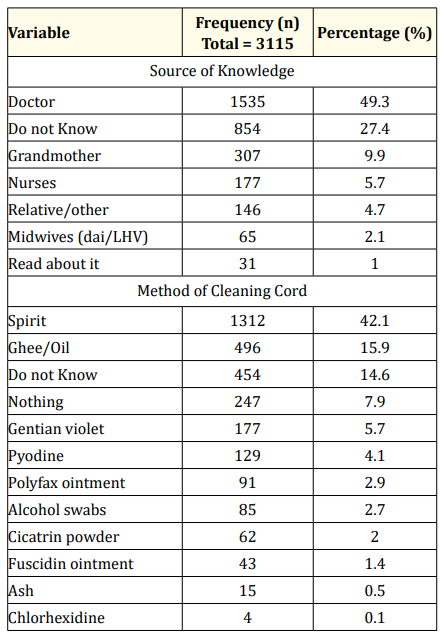

Most (77.5% - 2414) would apply an agent to the cord, commonest being methylated spirit (1312-42.1%) and ghee/oil (49615.9%). A small number (454 -14.6%) did not know of good practise. Antimicrobials were used by 1899 (61%). Only few adopted dry cord care (247-7.9%) and chlorhexidine (4-0.1%).

Medical personnel (doctors, nurses, and lady health workers) advised 1777 (57%) females, whereas grandmothers and close relatives influenced 453 (14.6%).

Conclusion: We need to educate our medical personnel as well as all available family members to bridge the gap between recommended and actual cord care practices.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 indorse prevention of deaths of newborns and children, aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to 25 per 1,000 live births [1]. However, Pakistan still has the world’s second-highest Neonatal mortality rate (41.2 per 1000 live births), in 2019 [2,3].

Neonatal sepsis contributes to 15.2% and tetanus to 1.2% of neonatal deaths. In an effort to reduce infections, the ‘Clean Birthing’ process have shown to be effective [4]. It comprises of 6 hygienic practices, which are clean hands of the birth attendant, clean delivery surface, clean perineum, clean instrument to cut the cord, clean cord tie, and clean cord care [5]. The importance to proper cord care is well justified because infections of cord (omphalitis) happen 0.7% in developing countries and 8-22% in developing countries, progressing onto sepsis and probable mortality [6-8].

In 2014, WHO updated the recommendations for postnatal cord care to “Daily chlorhexidine (7.1% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution or gel, delivering 4% chlorhexidine) application to the umbilical stump during the first week of life, for home deliveries especially in regions with high neonatal mortality (30 or more neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births). Clean and dry cord care is recommended for newborns born in health facilities or born at home in areas with low neonatal mortality. Use of chlorhexidine in these situations may be considered only to replace the application of a harmful traditional substance, such as cow dung, to the cord stump [9].

This study was conducted to document the frequency of different cord care practices in our population and its relation to sociodemographic factors, with the hope that it will help us analyse the extent of poor practices, so that we can better strategize to overcome this ongoing old problem.

We did a questionnaire-based cross-sectional study in 3 tertiary care hospitals in Lahore (Pakistan), which were Fatima Memorial hospital, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, and Mayo Hospital, over a period of 6 months, from July-2018 to June-2019. Of these Fatima Memorial Hospital is trust-based tertiary care hospital, providing care to both general and private patients, whereas other 2 are public Govt. funded tertiary care hospitals. Mayo Hospital does not have obstetric unit on premises and its neonatology caters to large number of referrals, but the other 2 have busy obstetric and neonatology units.

The sample size was calculated from online calculator [10]. The approximate size was 666 interviews for each hospital, keeping the confidence interval at 99% (z value=2.57), error of margin at 5%, and assumed prevalent poor cord care practices at 50%, all in line with another past study from Pakistan [11]. Non-probability convenient sampling was done to select interviewees.

Participating doctors interviewed mothers and their female attendants, during obstetric ward rounds, neonatal unit rounds, and neonatal outpatient clinics. Questions were asked according to a formatted questionnaire and answers recorded data about sociodemographic, attitude, and knowledge of cord care practices. To ensure the uniformity of data acquisition, the lead investigator and team leaders in each hospital, briefed their respective teams not only at the start but also held monthly debriefing sessions.

Verbal consent was taken, and anonymity of data was maintained. SPSS version 20 was used for descriptive and inferential analysis. Descriptive parameters were expressed as frequency and percentages. Chi-square test was used to identify any association of cord care practices with socio-demographic data, significant being the value of less than 0.05%.

No financial assistance was offered to the participants for the sake of interviews.

A total of 3115 females were interviewed in 12 months. The mean age was 32 + 8.1 years. The socio-demographic characteristics of participants are shown in table 1.

Table 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

Almost 2/3rd of our participants (71.3%) was married. 1889 (60.6%) of females (unmarried + married but no child + new mothers) answered us based on the observed or tutored family practices.

Majority (2191- 71.8%) of females resided in cities, especially in Lahore. Only 879 (28.3%) belonged to small towns and villages. Most (1925 -61.8%) of the participants had at least some years of school education, remaining did not attend any school. Housewives or stay home mothers comprised 64.1% of study population (1997). Amongst the careers mentioned, there were teachers (2628.4%), doctors (178-5.7%), nurses (128-4.1%), bank officers (77-2.5%), helpers, saleswomen and beauticians.

The attitudes about cord care are shown in table 2.

Table 2: Attitudes about Cord Care in Newborns.

In our study, widespread and indiscriminate use of bactericidal or bacteriostatic agents have been documented in 1899 (61%). Of these, the methylated spirit use was the most frequent (131242.1%). Other antimicrobials mentioned, include gentian violet, Pyodine (povidone-iodine solution), Polyfax ointment (polymixin B and bacitracin zinc), alcohol swabs (soaked in 70% v/v isopropyl alcohol), cicatrin powder (Neomycin sulphate and bacitracin), and Fucidin cream (fusidic acid). The application of Ghee (made from clarified butter) and vegetable oil was the second common agent (496-15.9%). Some females (0.4%) would use ash from burnt cow dung or burnt coal. Only 8% of participants would use WHO recommended methods of dry cord care (247-7.9%) and chlorhexidine (only 4 participants). It means 92%, including those who did not know of proper care method (454-14.6%) would use either unnecessary or harmful practices.

We also asked participants about the reason of their inclination towards a particular method of cord care. Medical-related personnel were the most common source of knowledge for our 55.3% of participants. Majority of these personnel were general practitioner doctors 47.7%, others were midwives, lady health workers (LHW), or dai (traditional midwife), working in respective localities of family residences. Grandmothers (10%) and other close relatives (5.3%) such as sisters or sisters-in-law also advised about cord care methods, likely advocating for the family traditions.

Since all the interviews were conducted in the hospitals, all babies had umbilical clamps used and cords were cut with clean scissors or blades.

We tried to see the correlation of addresses and educational status with the type of cord care, but there was no significant relation.

TThe umbilical cord connects the fetus to the placenta in utero. After birth it dries, shrivels, and then falls off, the whole process taking 5 to 15 days. During this period, there is usual colonization with non-pathogenic staphylococci and diphtheroid bacilli, but there is always risk of colonisation with pathogenic bacteria, causing omphalitis, neonatal sepsis, neonatal tetanus and death [12]. It explains the emphasis on clean instrument to cut the cord, clean cord tie, and clean cord care.

Over the counter availability and indiscriminate use of antimicrobial agents in our study is a troubling fact. Even more troubling is the rare use of WHO recommended Chlorhexidine gel (only 4 participants). The fact that 92% of our study population practised unsafe cord care and associated lack of correlation to socio-demographic data implies the widespread use of these practices in our whole society. Age, parity, urban status, literacy, and profession had no bearing. Even interviewed doctors were unaware of good practice.

Medical personnel (doctors, nurses, and midwives) had been the source of knowledge in 57% cases but only 8% of interviewees practised dry cord care and mere 4 participants knew about chlorhexidine. It shows a wide gap in knowledge transfer to the target population. Our study also demonstrates the role of relatives, especially grandmothers, in the propagation of family traditions especially with use of ghee/oils and ash. The influence of relatives and grandmothers in aspects of newborn care is well known [13]. It also implies the need to counsel not only mother, but as many family members as possible. Encouraging fact is the frank admittance of ignorance by one-fourth of participants, meaning an opportunity for effective counselling.

Methylated spirit (denatured alcohol), commonly called Spirit in Pakistan, contains ethanol and methanol, is antibacterial and antifungal. It is the most common choice in our study, similar in trend to studies in other parts of the world [14,15]. Methylated spirit can cause local skin irritation, prolonged cord separation time and have been reported for systemic absorption across the skin in a preterm baby [12].

Use of ghee (animal oil) or vegetable oil causes a change in pH, promoting colonisation of bacteria and delaying cord separation time. Application of oil and ash to cord in this age, in a major city of Pakistan, is alarming and shows the forceful impact of tradition and weakness of propagation or counselling for safe cord care.

Chlorhexidine is a cationic bisguanide, active against most gram-positive organisms, especially against resistant staphylococci. It has residual activity and acts even in the presence of blood [17]. Many studies show that application of chlorhexidine to the cord reduces omphalitis by 50%, neonatal sepsis by 32% and neonatal mortality by 12% [18-22]. There is high-quality evidence that chlorhexidine skin or cord care in the community setting results in a 50% reduction in the incidence of omphalitis and a 12% reduction in neonatal mortality. However, there are some concerns regarding local dermatitis, rare neurotoxicity, and severe eye damage from erroneous use [17].

Our participants have mostly been from urban areas. We need more studies, from other areas, including remote settlements and villages, so to form consensus statements which are culture friendly as well as safe, evidence-based and easily propagated.

Our study shows that there is a wide gap between available guidelines and actual practices regarding cord care. We need to strengthen the education of the community with special emphasis on medical personnel.

Copyright: © 2021 Zahid Anwar., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.