VL Jayasimha1 and Shaswati Dey2*

1Professor and HOD Department of Microbiology, SSIMS and RC, Davangere, Karnataka, India

2Junior Resident, Department of Pediatrics SSIMS and RC, Davangere, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author: Shaswati Dey, Junior Resident, Department of Pediatrics SSIMS and RC, Davangere, Karnataka, India.

Received: August 24, 2021; Published: September 29,2021

Citation: VL Jayasimha and Shaswati Dey. “Clinicobacteriological Study of Neonatal Septicemia with Special Reference to Sepsis C-Reactive Protein and Procalcitonin”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 4.10 (2021): 89-97.

Background: Neonatal sepsis can be described as an invasive bacterial infection which occurs within a month of life. Neonatal sepsis can present in two forms based on the age of onset, the one within 48hrs of birth is early onset sepsis (EOS) and the other late onset sepsis (LOS) which occurs after 48hrs after the birth. The incidence is 11 - 24.5/1000 live births in India.

Aim of the Study: This study aims at giving an outline of the load of bacterial sepsis in the developing countries in newborn population. The focus will be on the pathogens mostly implicated, their antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and management and finding out the diagnostic performance of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in the intensive neonatal care unit as a early diagnostic marker.

Methodology: This study was conducted in Department of Microbiology at of S.S. Institute of Medial Science and Research Centre, Davangere. As per the criteria by Vergnano, clinically diagnosed neonates with septicaemia are included in the study. The study group comprised of 145 suspected cases of neonatal septicaemia in the neonatal intensive care unit. Blood culture by automated blood culture system was done along with C Reactive protein estimation by Nephelometry and Procalcitonin by Immunofluorometry.

Results and Discussion: In the present study out of total 145 cases, female were 64 (44%) and males were 81 (55%). In this study clinical feature like seizures and hurried breathing, grunting are seen in most of the neonates with Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli and S. aureus as major organisms. In this study out of 145 cases CRP positive cases were 51 (35%) and CRP negative cases were 94 (64%).

In this study out of 62 blood culture positive cases, CRP was positive in 32 cases and out of 83 blood culture negative cases 64 were negative.

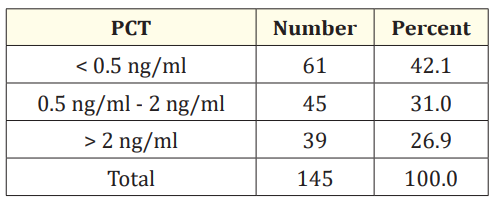

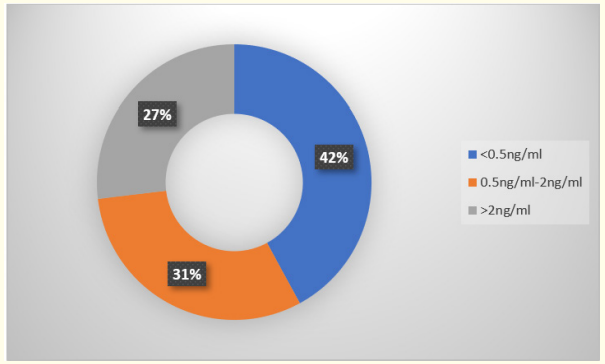

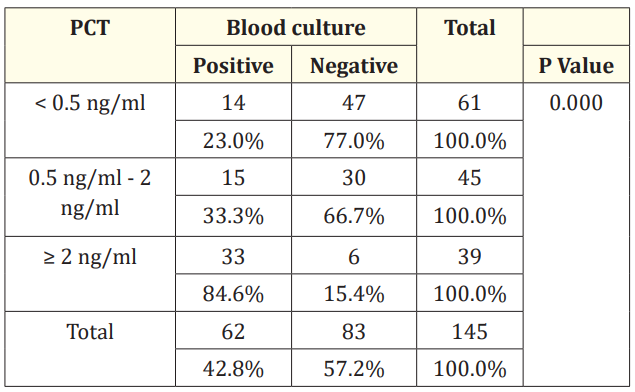

In this study, among 62 positive blood cultures 48 cases had positive procalcitonin. We found positive procalcitonin in 36 cases where blood culture was negative. Out of 83 blood culture negative cases 47 had negative procalcitonin. In this study < 0.5 ng/ml PCT was found in 61 (42%), 0.5 - 2 ng/ml was found in 45 (31%), > 2 ng/ml was found in 39 (27%). It has sensitivity of 57.14% and specificity of 77.05%, positive predictive value of 77.4% and negative predictive value of 56.63%.

Keywords: Neonatal Septicemia; C-Reactive Protein; Procalcitonin; Early Onset Sepsis (EOS); Late Onset Sepsis (LOS)

One of the important causes of morbidity and mortality in newborns is neonatal sepsis which is a systemic infection occurring within a month of life. Neonatal sepsis can present in two forms based on the age of onset, the one within 48 hrs of birth is early onset sepsis (EOS) and the other late onset sepsis (LOS) which occurs after 48 hrs after the birth. Viral or fungal sepsis may also occur at 7 days of life and must be ruled out from bacterial sepsis [1-4].

The incidence and mortality are greater among very-low birthweight (VLBW) infants are considered exclusively; for neonates with an extremely low birth weight of < 1,000g, the incidence is 26 per 1,000 and 8 per 1,000 livebirths in very low birth weight neonates of between < 1500 gms [5].

Pathogens responsible for early-onset neonatal sepsis are normal flora of the maternal genitourinary tract, which may ascend when the amniotic membranes rupture or prior to the onset of labor, leading to contamination of the amniotic fluid, causing an intra-amniotic infection [6]. Thus, the newborn may acquire the infection either in utero or intrapartum. Maternal risk factors for EOS includes, dietary intake of contaminated foods with Listeria monocytogenes, can arise before labor and delivery [7]. In pregnancy, maneuvers like cervical cerclage and amniocentesis, which increase the rates of intra-amniotic infection by rupture of amniotic cavity. Prolonged rupture of membranes, fever, vaginal colonization with group B streptococcus (GBS), and GBS bacteriuria are the important maternal factors during labor [8].

IgG antibodies in maternal serum against specific capsular polysaccharides of GBS is protective against infection with the relevant GBS strain in their neonates, whereas increased risk for GBS EOS has been shown in neonates born to mothers with low titers [9]. Chorioamnionitis, is also a major risk factor for neonatal sepsis which occurs as a result of longer length of labor and membrane rupture, repeated digital vaginal examinations, placement of internal fetal or uterine monitoring devices [10].

In utero swallowing of infected amniotic fluid by the fetus may lead to intrapartum sepsis, and colonization of the skin and mucus membranes by pathogens involved in chorioamnionitis which leads to high incidence of sepsis in newborns delivered to mothers with chorioamnionitis [11].

Infant factors leading to early-onset sepsis are prematurity/low birthweight, congenital anomalies and low APGAR scores [12]. In premature neonates immature immune system, diminished barrier function of the skin and mucus membranes, multiple invasive procedures like intravenous (i.v.) access and intubation in ill preterms are important risk factors [13]. In term and preterm infants GBS and Escherichia coli, which account for approximately 70% of infections are most commonly and frequently involved in EOS. Additional pathogens in minority of cases, are other Streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus species, Enterobacter species, Haemophilus influenzae and Listeria monocytogenes [14].

The burden of disease attributable to E. coli and other gramnegative rods is increased, leading to gram-negative sepsis the most common etiology of EOS in preterm and VLBW infants when considered separately [15].

Prenatal screening and treatment with intrapartum antibiotics (IPA) has resulted in decrease in the frequency of early-onset GBS disease, however GBS remains one of the most common causes of EOS.

Acute-phase reactants: The two most commonly studied acutephase reactants in neonatal sepsis are CRP and procalcitonin. Within 6 to 8h of infection CRP level rises and reaches maximum at 24h. Following inflammation IL-6 will be released, which stimulates an increase in CRP concentrations. A value of 10 mg/liter is the most commonly used cutoff in most published studies. CRP level is usually upto 5 mg/liter in Viral infections. When CRP measured within 24to 48h of onset of infection it gives better predictive value [16]. Increasing CRP levels is a superior predictor than individual values. Antibiotics can be safely discontinued if repeated values of CRP are normal which is strong evidence against bacterial sepsis. Procalcitonin is a propeptide of calcitonin that is significantly elevated during infections in neonates, children, and adults and produced mainly by monocytes and hepatocytes with half-life of about 24h in peripheral blood. The normal level for newborns within 72h of age is usually 0.1 ng/ml. In sepsis, PCT is synthesized by macrophages and the monocytic cells of the liver. Within 2 hours of an infectious episode PCT level increases, reaches maximum at 12 hours, and returns to normal level within 2 to 3 days in healthy adult volunteers. Procalcitonin concentration have more sensitivity less specificity than CRP concentration [17]. Definitive status of neonatal sepsis has not been established in central Karnataka as such. Little literature is available on CRP and procalcitonin levels in Neonatal sepsis.

The aim of this study is to analyse the burden of bacterial sepsis in the newborn population in developing countries with mainly focusing on the pathogens mostly implicated, their antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and management and to determine the diagnostic performance of procalcitonin and C -reactive protein as early diagnostic markers for the detection of neonatal sepsis in the intensive neonatal care unit.

This study was conducted in Department of Microbiology at of S.S. Institute of Medial Science and Research Centre, Davangere. As per the criteria by Vergnano, clinically diagnosed neonates with septicaemia are included in the study. The study group comprised of 145 suspected cases of neonatal septicaemia in the neonatal intensive care unit.

History of every neonate is included in the study regarding gestational age, birth weight, gender and other aspects as mentioned in the proforma. After clinical examination of the neonate by paediatrician, cases were considered for laboratory investigations.

About 1 ml of blood was inoculated into 10 ml of brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and processed as per the protocol and incubated for one week at 37°C and was checked daily for evidence of bacterial growth in Automated blood culture system [18].

For positive broth cultures, subcultures were done next day on blood agar, Mac Conkey agar and Chocolate agar and were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. If no growth occurred on plates after 24 hours, subsequent subcultures were done as per the standard procedures.

The grown bacteria were identified by colony morphology, Gram stain and standard biochemical tests. As per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guideline (CLSI). The antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method for the bacterial isolates. ATCC control strains were used accordingly as per standard procedures [18].

Estimation of serum CRP: Quantitative analysis was done by turbidometric method (MISPA NEPHELOMETRY).

Principle: This is a latex enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay. CRP samples attaches to specific anti-CRP antibodies, agglutinates when adsorbed to latex particles. Quantity of CRP in the sample as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guideline (CLSI) is directly proportional to the agglutination [19].

3 ml of serum sample was collected from above patients and were subjected to estimation of Procalcitonin by immunofluorescent method. The procedure for the estimation was done as per the manufacturer guidelines (Agappe Diagnostics Ltd.)

Table 1: Age distribution.

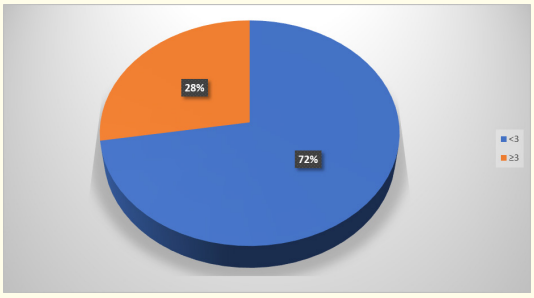

Graph 1: Age distribution.

In the present study maximum number of neonates were

Table 2: Sex distribution.

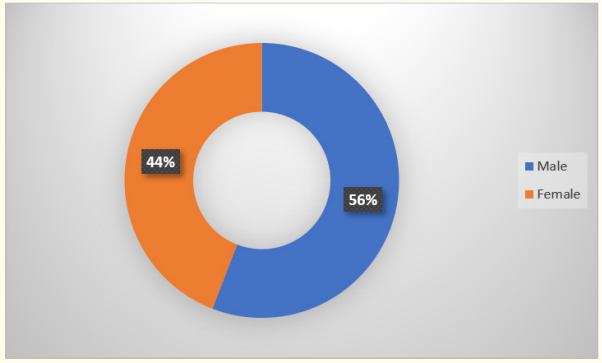

Graph 2: Sex distribution.

In the present study out of total 145 cases, female were 64 (44%) and males were 81 (55%).

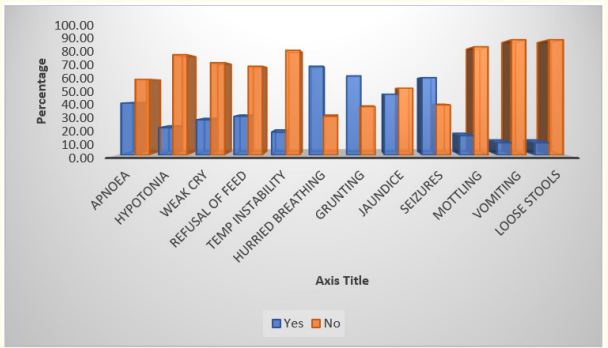

Graph 3: Clinical features and blood culture positivity.

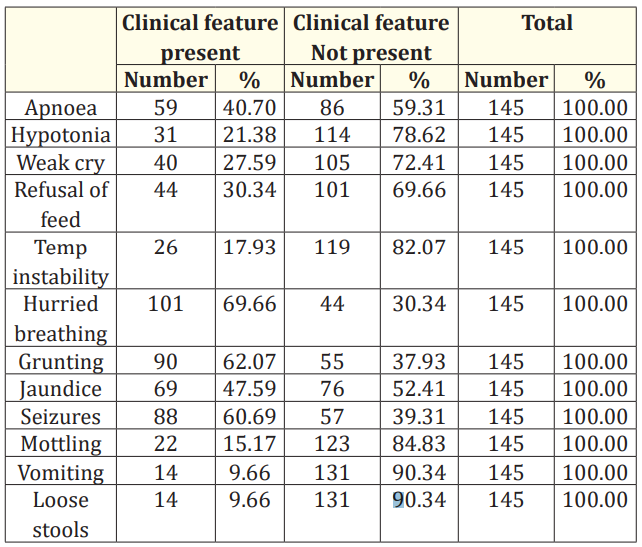

Table 3: Clinical features and blood culture positivity.

In this study clinical feature like seizures and hurried breathing, grunting are seen in most of the neonates.

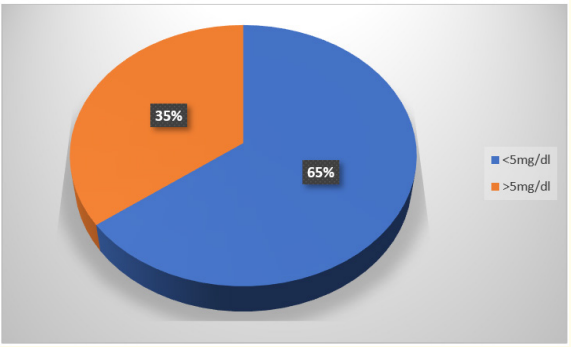

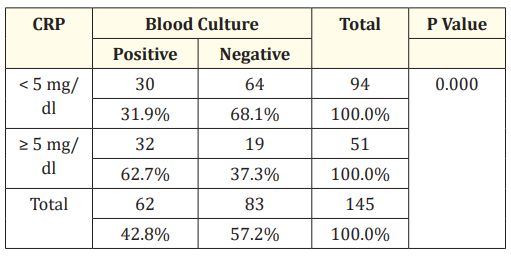

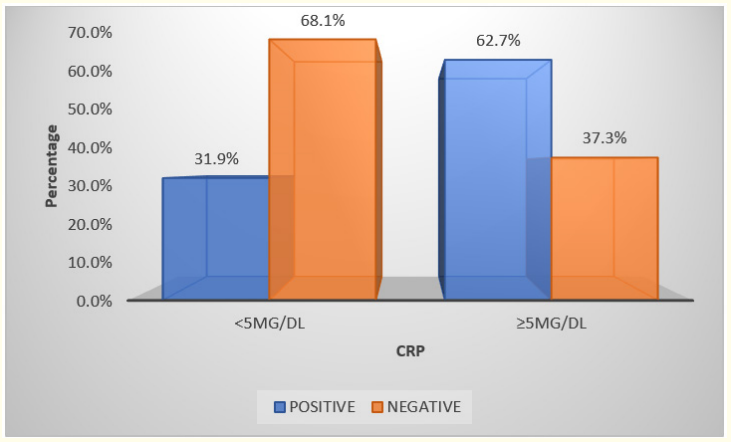

Table 4: CRP.

Graph 4

In this study out of 145 cases CRP positive cases were 51 (35%) and CRP negative cases were 94 (64%).

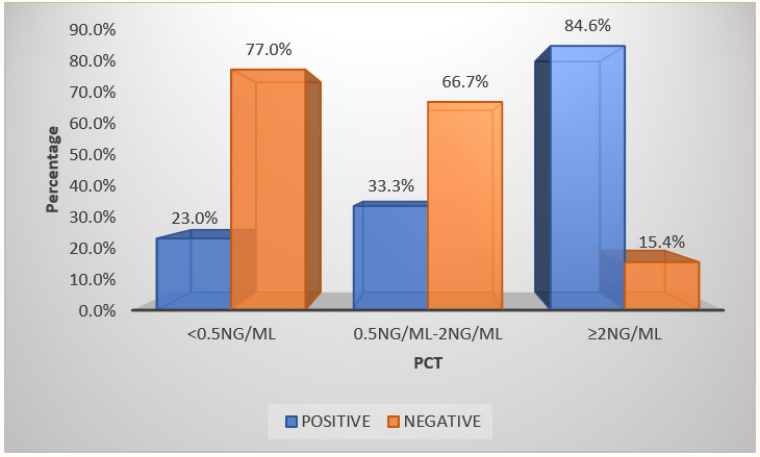

Table 5: Procalcitonin

Graph 5

In this study < 0.5 ng/ml PCT was found in 61 (42%), 0.5 - 2 ng/ ml was found in 45 (31%), > 2 ng/ml was found in 39 (27%). It has sensitivity of 57.14% and specificity of 77.05%, positive predictive value of 77.4% and negative predictive value of 56.63%.

Table 6: Clinical features and CRP.

In the present study, clinical features like hurried breathing (65.3%), seizures (60%) and grunting (60%) were commonly found to be associated with CRP positive cases.

Table 7: Clinical features and Procalcitonin.

In our study grunting (40%), hurried breathing (43%), seizures (35%) are found in most of the neonates.

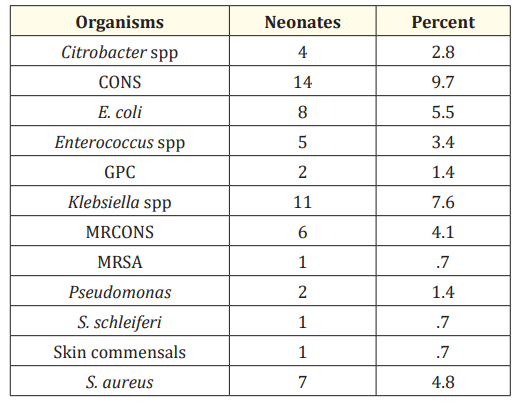

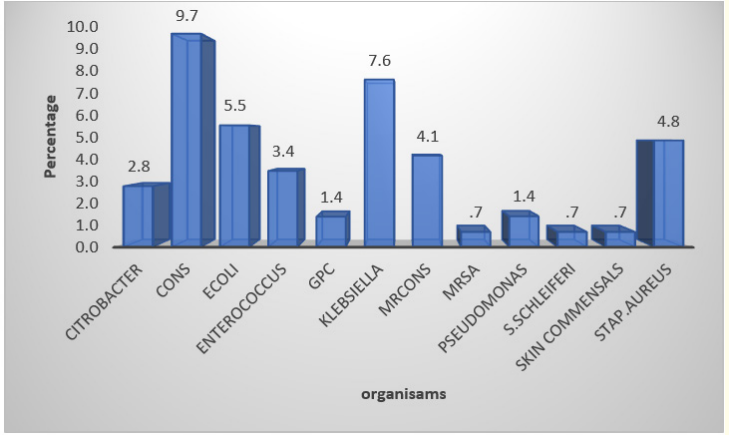

Table 8: Organisms isolated in blood culture.

In our study Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli and S. aureus pathogens were found to be identified in blood culture positive cases including CONS.

Graph 6

Table 9: CRP and blood culture.

Graph 7

In this study out of 62 blood culture positive cases, CRP was positive in 32 cases and out of 83 blood culture negative cases 64 were negative.

Table 10: Procalcitonin and blood culture.

Graph 8

Sepsis is one of the most common cause of neonatal mortality and its diagnosis and management remains a challenge for health care workers [20]. Early diagnosis of sepsis and instituting antibiotic therapy at the earliest plays a crucial role in reducing the mortality rate.

Even though blood culture is the gold standard for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis, there is need of other diagnostic indicators of sepsis, as its positivity rate is low and is affected by blood volume inoculated, prenatal antibiotic use, level of bacteraemia and laboratory capabilities.

The laboratory tests are useful in evaluation of newborn with signs of infection vary. Laboratory tests like complete blood count is difficult to interpret because it varies significantly with day of life and gestational age in neonatal period. In early onset sepsis low value of white blood cells, low values of absolute neutrophil counts and high immature/total ratio are seen compared to late onset sepsis which shows high or low white blood cells counts, high absolute neutrophil counts, high immature to total ratio and low platelet counts are associated [21]. All of these findings have low sensitivities despite their association with infection.

Taking serial CRP determinations 24 - 48 hour after the onset of symptoms achieves a sensitivity of 74 - 89% and specificity of 74 - 95% compared to single value of C- reactive protein which has unacceptable low sensitivities, especially during the early stage of infection [22].

Procalcitonin increases faster than CRP, with overall sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 79% making it a very appealing biomarker.

In a study done in Sion hospital Mumbai by Anuradha., et al. on sex incidence in neonatal sepsis found that male babies were commonly involved.

In our study also it was found that 56% were male babies whereas 44% were female. It is said that function of thymus and synthesis of immunoglobulins have a role in resistance against infection. And the genes for the same are located on X chromosome. Thus, it is found that females have double dose of genes affecting these factors compared to males [23].

Neonates with age 3 days or less than 3 days diagnosed with sepsis is said to be early onset sepsis. It is normally considered as a result of vertical transmission from mother during labour and delivery. Maternal risk factors include fever, urinary tract infection, colonisation with group B streptococcus, premature rupture of membranes. Foetal factors include prematurity, low APGAR score, low birth weight, male sex.

In our study also Early onset sepsis (72%) was found to be significant than late onset sepsis (27%).

V. Dhanalakshmi., et al. conducted a study in a medical college, Madurai, India had showed clinical feature correlation with neonatal sepsis. The study emphasised that the clinical features like hurried breathing, seizures, weak cry, refusal of feeds, vomiting, diarrhoea, apnoea, temperature instability, grunting and jaundice are associated with sepsis and many neonates had more than one manifestations [24].

In our study also we found that many neonates had more than one clinical manifestation among which hurried breathing, grunting, seizures and jaundice are more commonly found.

Tillet and Francis in 1930 first described C-reactive protein. They concluded that it is a protein that helps in acute inflammation by complement binding to foreign or damaged cells and reaching maximum levels after fifty hours. CRP provides good idea regarding septicaemia diagnosis along with clinical evidence of the disease [25].

Effat Hisamuddin., et al. did a study in a neonatology unit in KRL general hospital aimed to find the time period when antibiotics treatment can be safely discontinued in case of suspected neonatal septicaemia using CRP as a tool in neonatal sepsis [26].

Singh., et al. observed that C-reactive protein had 80% sensitivity, 91% specificity and 92% positive predictive accuracy which was highest in their study.

In our study according to the literature and the method used to estimate CRP, value less than 5 mg/dl was taken as CRP negative cases and > 5 mg/dl was taken as CRP positive cases. And it was found that 35% were positive and 64% were negative. In this study out of 62 blood culture positive cases, CRP was positive in 32 cases and out of 83 blood culture negative cases 64 were negative. It has sensitivity of 48.39%, specificity of 20%, positive predictive value of 31.9% and negative predictive value of 37.25%. Subsequent studies have suggested that serial CRP are more reliable and useful in detection of sepsis [27].

PCT has been investigated intensively in neonatal sepsis for its diagnostic role. PCT levels were very low in those with no infections compared to high concentration of plasma PCT in infants with severe infection. Chiesa., et al. stated that an increase in PCT levels in early and late onset of neonatal sepsis is quite reliable. Noninfectious condition which induce abnormal values of CRP are perinatal asphyxia, respiratory distress syndrome, brain haemorrage and meconium aspiration syndrome and post surgical period [28].

PCT is a potential diagnostic variable for the diagnosis of bacterial infection because of the unique feature that PCT level increase in bacterial and fungal infections, but remain unchanged even in severe viral infections and other inflammatory diseases. Thayi S., et al. conducted a study in NICU of GSL Medical college, Andhra Pradesh, India. According to the study, out of 20 neonates with clinical sepsis 18 had negative PCT (0.5 ng/ml) and 2 had PCT weakly positive (0.52 ng/ml). Out of 18 blood culture positive/confirmed sepsis cases, PCT was found to be positive in 16 cases, with a sensitivity of about 88.8 percent [29].

In neonates in all sepsis groups PCT level was significantly higher compared to those in the control group (P < 0.05). At a cut-off of 0.5 ng/ml, the negative predictive value (NPV) of PCT was 80% and the positive predictive value (PPV) 39%.

In our study we found that out of 62 positive blood cultures 48 cases had positive procalitonin. We found positive procalcitonin in 36 cases where blood culture was negative. Out of 83 blood culture negative cases 47 had negative procalcitonin. It has sensitivity of 22.58%, specificity of 60%, positive predictive value of 22.95% and negative predictive value of 42.86%.

Desai K J., et al. showed that Gram negative bacteria were 67.85% and Gram positive bacteria were 28.57%.

Jyothi P., et al. in their study showed Gram negative bacteria accounted for 55.7% of cases and Gram positive 44.3% cases. Klebsiella spp, Acinetobacter spp and coagulase negative staphylococcus were most common organisms isolated [30].

According to James C, Gram negative enteric bacteria were the most common causative organisms. Several factors may be responsible for the susceptibility of the neonate to infection with these agents.

Postnatal the infant which are admitted in NICU are exposed to Gram negative organisms through humidification apparatus, resuscitation equipment and articles used in daily care. In the global perspective, group B Streptococcus (GBS), Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae and Listeria monocytogenes are the microorganisms most commonly associated with early onset infection. In case of late onset infection causative organisms are Coagulase negative Staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Candida, GBS, Serratia, Acinetobacter and anaerobes [31].

In the present study Gram positive organisms mainly Staphylococcus aureus was found in most of the cultures. Gram negative organism which was more common is Klebsiella. The Gram positive cocci were found more than Gram negative bacilli.

The antimicrobial sensitivity pattern differs in different hospital studies as well as at different hospital studies as well as at different times in same hospital. This is because as a result of indiscriminate use of antibiotics leading to emergence of resistant strains [32]. Tsering D C., et al. stated in their study Staphylococcus aureus was the most common Gram-positive organism isolated. More than 70% of which were resistant to Penicillin, but were sensitive to Clindamycin (70%) and Vancomycin (40%). I Roy., et al. shown in their study that resistance to Penicillin was frequent in S. aureus 95% and CONS 89%, Resistant to Cefotaxime ranged from 63% to 65% and that to Ceftazidime ranged from 40% to 53% of Gram negative isolates [33]. A study by Amutha Chelliah., et al. showed that there were a total of 30 (27%) Staphylococcus aureus isolated, out of which 17 (56%) were Methicillin resistant. Vancomycin is effective against all the MRSA strains [34]. 100% sensitive to Vancomycin is shown by Enterococcus faecalis and coagulase negative Staphylococci were also. In our study Linezolid was sensitive to Staphylococcus aureus and Meropenem sensitive to Gram negative bacilli like Klebsiella.

Copyright: © 2021 VL Jayasimha and Shaswati Dey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.