Petronila Tabansi1* and Onubogu UC2

1Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt, Choba, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

2Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, College of Medical Sciences, Rivers

State University, Rivers State, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Petronila Tabansi, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt, Choba, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

Received: April 15, 2021; Published: April 23, 2021

Citation: Petronila Tabansi and Onubogu UC. “A Comparative Analysis of the Serum Electrolytes, Urea and Creatinine Profile of Children on Diuretic Therapy for Cardiac Anomalies-related Heart Failure”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 4.5 (2021): 34-39.

Introduction: In Nigeria, children with acquired and congenital heart diseases (CHD) lack timely access to corrective surgeries due to scarcity of cardiac surgical centers and high cost of care; hence they are placed on diuretic therapy for prolong periods for symptomatic relief of the ensuing heart failure. Electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalemia and hyponatremia are known complication of diuretic therapy and have an adverse effect on morbidity and mortality of these children. Considering the risk posed by diuretics, and the inherent risk for renal injury due to hypoperfusion from heart failure, it becomes imperative to monitor their electrolyte, urea and creatinine levels for early intervention and a better outcome.

Aim: To determine the serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine values of children with cardiac pathologies in heart failure and make comparison with healthy controls.

Methodology: This was a prospective case-control study of children with cardiac pathologies on diuretic therapy for heart failure and their age and sex matched healthy controls. Biodata, echocardiography diagnoses and blood samples for serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine were obtained and comparison made.

Results: There were 83 (50%) Subjects and 83 healthy Controls with age range from 2 days to 16 years. Majority of the study population were less than 1year of age. Acyanotic CHD was the commonest cardiac pathology detected in 55 (66.3%), while acquired heart diseases constituted 3.6% of cases. Subjects had significantly lower levels of sodium (p = 0.0001), potassium (p = 0.0001) and bicarbonate (p = 0.004); and higher levels of urea (p = 0.014) and creatinine (p = 0.002). Among Subjects, the Mean sodium and bicarbonate levels were lowest in those with cardiomyopathies while Mean potassium level was lowest in those with cyanotic CHD.

There were significant intergroup differences in Mean serum creatinine (p = 0.000).

Conclusion: Children on diuretic therapy for heart failure had comparatively lower levels of serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine.

Keywords: Cardiac Pathologies; Diuretics; Heart Failure; Serum Electrolytes; Urea and Creatinine

Heart failure is a known complication of congenital and acquired heart diseases in children and a major cause of morbidity and mortality [1]. It is a constellation of symptoms and signs emanating from the pathophysiologic consequences of a reduction in cardiac output and inability to meet the body’s metabolic demand [2]. In Nigeria, prevalence of heart failure in children ranges from 5.8% to 15.5% [3-6] mainly due to uncorrected congenital and acquired heart diseases [5-8] as cardiac surgical centers are few in the country [9,10]. Hence, most children with congenital and acquired heart diseases are on chronic medical therapy to control the ensuring heart failure and consequent fluid overload [11,12].

Diuretics play a key role in anti-heart failure medical therapy due to their effect of renal salt and water loss (diuresis) thereby reducing cardiac pre-load, which result in symptomatic relieve [13,14]. However, the renal salt loss may also result in electrolyte derangements such as hyponatremia and hypokalemia; especially with use of high and moderate ceiling diuretics such as furosemide and thiazides respectively [13-15]. Spironolactone is a weak diuretic with potassium sparing effect that is also used to counteract the effect of potassium loss by high/moderate ceiling diuretics [15,16]. However, it may cause hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, mild acidosis and transient elevation of serum urea nitrogen [16]. These electrolyte imbalances portend increased morbidity and even mortality as they affect the body milieu and increase the risk for adverse cardiovascular and neurological complications such as arrhythmias and seizures in extreme cases [17-20].

Heart failure is also a known risk factor renal injuries and progressive renal malfunction which in turn adversely affect the outcome of children with heart failure [21-24]. This is because heart failure results in poor renal perfusion leading to activation of compensatory neurohormonal interactions which if persistent (as seen in uncorrected CHD in heart failure), combined with use of medications can result in deleterious consequences in renal function which may be initially subtle [25].

Some studies have demonstrated presence of electrolyte imbalance in children with congenital and acquired heart diseases who are on chronic diuretic therapy for chronic heart failure [26]. Sadoh., et al. [26] in Benin, Nigeria showed lower values for plasma sodium levels among subjects on diuretics therapy for chronic heart failure when compared to age and sex matched controls. Considering the consequences of undetected anomalies in electrolytes and renal function in children with heart failure, it becomes imperative that clinicians should routinely assess the serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine levels of these children so as to take preventive measures to reduce morbidity and mortality.

To determine the serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine values of children with congenital and acquire heart disease in chronic heart failure and make comparison with healthy controls.

This was a case-control study undertaken over 8 weeks from 4th January to 28th February 2020. The cases (Subjects) were children with echocardiography diagnoses of congenital and acquired heart diseases attending the paediatric cardiology clinic of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH) who were all on appropriate doses (based on their weight) of high ceiling diuretics (furosemide) and a potassium sparing diuretics (spironolactone) for heart failure. The Controls were normal healthy children on follow-up clinic visits for mild illness such as acute non-severe pneumonia, tonsillitis, and malaria. The Controls were examined to have fully recovered from their mild ailments and not on any form of medication or have had diarrhea in the previous two weeks prior to recruitment. The Subjects and Controls were matched for age and sex.

Data obtained included age, gender and echocardiography diagnoses of heart disease (in the Subjects). Blood samples for the determination of serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine were collected from both groups according to standard protocol [27]. A freshly passed urine sample was also collected for urinalysis to check for proteinuria.

The UPTH laboratory reference values for electrolytes as shown below was considered normal and values outside the range were considered abnormal:

Data was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet® and analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics version 23. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentage proportions, while continuous variables were expressed in means and standard deviation. Comparison of group means was done using Independent sample T test to determine mean differences. Test of statistical significance was set at 95% confidence interval with a p value of 0.05.

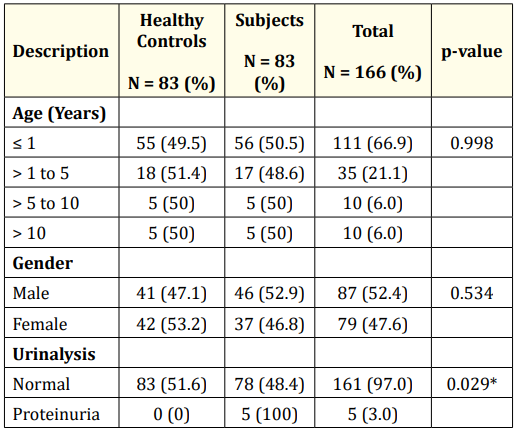

A total of 166 study participants were recruited 83 (50%) Subjects with cardiac pathology (on diuretic therapy for heart failure), and 83 healthy Controls with no underlying cardiac pathology. Their age ranged from 2 days to 16 years. There was no significant difference among the age distribution of the study population (p = 0.998). Children aged less than 1year contributed to a majority of the study population being 56 (50.5%) for Subjects and 55 (49.5%) for Controls. Majority of the Controls were females 42 (53.2%) while majority of the Subjects were males 46 (52.9%) although the difference in gender distribution was not statistically significant (p = 0.534). There was a significant difference in the prevalence of proteinuria (p = 0.029) as only children with a cardiac defect were found to have proteinuria in their urinalysis 5 (100%) (Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of study population. *: (Significant).

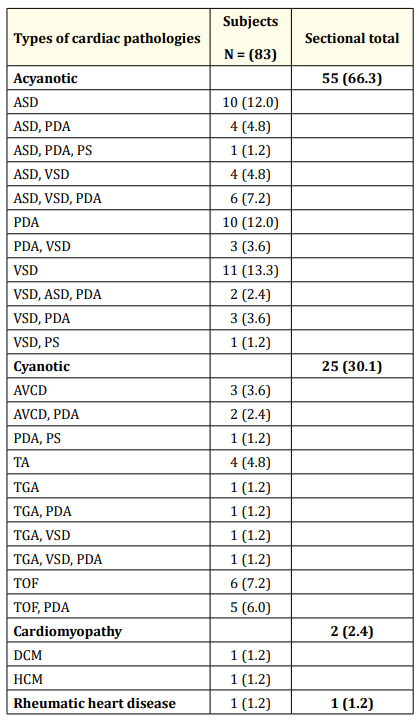

Among those with cardiac pathology, acyanotic congenital heart disease was the commonest 55 (66.3%), with single heart defects seen in 31 (56.4%) and multiple defects seen in 24 (43.6%). The commonest acyanotic congenital heart disease seen was VSD 11 (13.3%), followed by ASD 10 (12.0%) and PDA 10 (12.0%). Cyanotic congenital heart disease was seen in 25 (30.1%), among whom multiple heart defect were more common 17 (68%) while single defect constituted 32% (8 Subjects). Tetralogy of Fallot with or without coexisting PDA was the commonest cyanotic CHD seen in 11 (13.2%). Acquired heart diseases constituted only 3.6% (3 Subjects) of the cardiac pathologies with only one person having Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD) while the other two had cardiomyopathies. This is illustrated in table 2.

Table 2: Pattern of cardiac pathologies among the subjects.

Key: ASD: Atrial Septal Defect; VSD: Ventricular Septal Defect; PDA:

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA); PS: Isolated Pulmonary Stenosis;

TOF: Tetralogy of Fallot; TGA: Transposition of the Great Arteries;

TA: Truncus Arteriosus; DCM: Dilated Cardiomyopathy; HCM: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy.

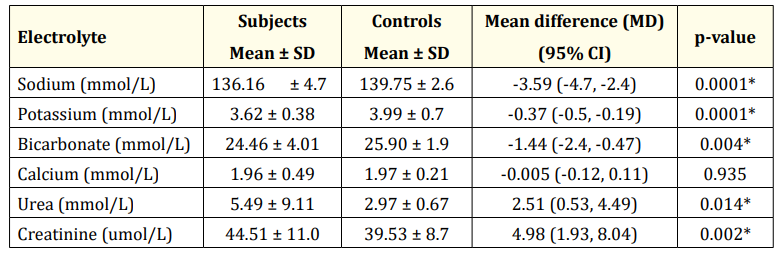

Table 3 shows that Subjects had significantly lower levels of serum sodium (MD: -3.59 (95% CI: -4.7, -2.4, P = 0.0001), potassium (MD: -0.37 (95% CI: -0.5, -0.19, p = 0.0001) and bicarbonate (MD: -1.44 (95% CI: -2.4, -0.47, p = 0.004). Subjects also had higher levels of serum urea (MD: 2.51 (95% CI: 0.53, 4.49, p = 0.014) and creatinine (MD: 4.98 (95% CI: 1.93, 8.04, p = 0.002).

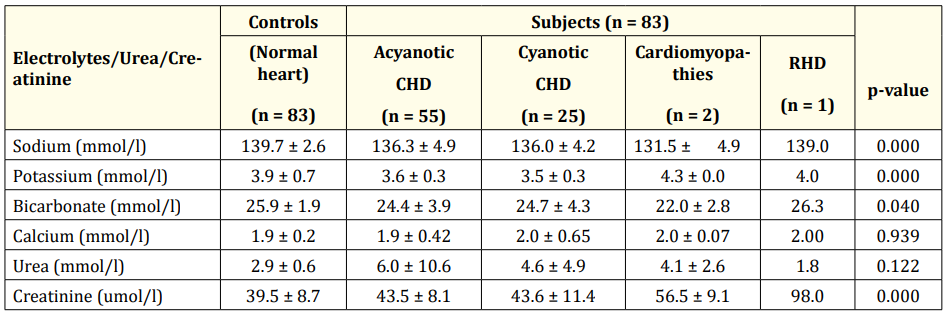

Evaluation of the electrolytes, urea and creatinine levels amongst the subjects showed that the lowest levels of Mean serum sodium and bicarbonate were seen in those with cardiomyopathies at 131.5 ± 4.9 (mmol/L) and 22.0 ± 2.8 (mmol/L) respectively; while the lowest Mean serum potassium level was seen in those with cyanotic congenital heart diseases 3.5 ± 0.3 (mmol/L).

The highest serum urea level was seen in Subjects with acyanotic congenital heart disease at 6.0 ± 10.6 mmol/l although there was no significant intergroup difference in Mean serum urea levels. The highest serum creatinine level was seen in the one patient with Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD). There were significant intergroup differences in Mean serum creatinine levels as shown in table 4.

Table 3: Comparison of serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine among subjects and controls.

Table 4: Comparison of serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine levels according to cardiac pathologies. *CHD: Congenital Heart Diseases; RHD: Rheumatic Heart Disease.

This study showed that most children with cardiac pathologies in heart failure who are on diuretic therapy (frusemide and spironolactone) have electrolyte levels maintained within the normal ranges. However, their Mean sodium, potassium and bicarbonate levels were significantly lower than age and sex matched healthy controls. This comparative difference may be related to the diuretic effect of frusemide among the Subjects which caused renal sodium and potassium loss, even though the overall electrolytes levels were still maintained within normal limits. Similar observations have been noted by Sadoh., et al. [26] in Benin, Nigeria and Arampatzis., et al. [29] in Bern, Switzerland. It thus appears that the standard combination of furosemide and spironolactone used in the therapeutics of heart failure in children awaiting definitive surgical correction of cardiovascular lesions does not result in significant electrolyte imbalance.

Congenital heart diseases constituted the majority of cardiac pathologies seen among the Subject population with acyanotic CHD proportionally more than cyanotic CHD. This finding is not surprising as CHD has been documented in literature as common causes of heart failure in children [30,31]. Common acyanotic CHD seen in the study Subjects were VSD, ASD and PDA while Tetralogy of Fallot was the most common cyanotic CHD seen followed by truncus arteriosus.

Sub-analysis of the electrolyte profile of the study Subjects showed that the serum sodium was significantly lower in patients with cardiomyopathy while the serum potassium was significantly lower in those with cyanotic congenital heart diseases. These observations may be related to the dosages of diuretics used as higher limits of dosing may be required for symptomatic control in children with advanced cardiomyopathy or certain cyanotic CHDs with increased pulmonary blood flow, thus increasing the risk for electrolyte renal losses and lower serum levels.

The serum calcium levels in both the Subjects and Controls were mildly reduced with no significant differences between the two groups. Although furosemide is known to increase urinary excretion of calcium thereby risk hypocalcemia, the observation of sub-clinical hypocalcemia seen in both the Subjects and Controls in the present study suggest background subtle calcium and/or vitamin D deficiency and requires further investigation.

Regarding the serum urea and creatinine levels, this study revealed that the Subjects had higher serum levels of both when compared to the healthy Controls, although the overall Mean serum urea and creatinine were within normal limits. This may be explained by the higher losses of body water from diuretics leading to contraction of intravascular volume and some level of dehydration raising serum urea levels. Furthermore, heart failure is a known risk for acute kidney injury and the significantly higher levels of creatinine seen among the subject population in this study in addition to the proteinuria which was detected only in the Control group should trigger clinicians to monitor renal function and serum electrolytes levels on a regular basis for appropriate early adjustment of medication and institution of other interventions to forestall progression.

The study concludes that children with cardiac pathologies on diuretic therapy for heart failure have electrolyte, urea and creatinine values within normal ranges. However, when compared to age and sex matched controls, they had significantly lower Mean serum electrolytes and higher Mean serum urea and creatinine levels.

The study recommends regular monitoring of the serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine levels in children on diuretic therapy for congenital and acquired heart diseases in heart failure.

Copyright: © 2021 Petronila Tabansi and Onubogu UC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.