Mitzi Avis G Panuda, Anabella S Oncog* and Maribeth M Jimenez

Department of Pediatric Medicine, Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital, Philippines

*Corresponding Author: Anabella S Oncog, Department of Pediatric Medicine, Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital, Philippines.

Received: February 19, 2021 ; Published: March 29, 2021

Citation: Anabella S Oncog., et al. “The Effect of Kangaroo Mother Care on the Morbidity and Mortality of Low Birth Weight Babies Admitted in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 4.4 (2021): 76-87.

Objective: To determine the effect of kangaroo mother care (KMC) on the morbidity and mortality of low birth weight babies admitted in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital.

Methodology: This is a descriptive retrospective study of all neonates with birthweights < 2000 grams born from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013 (pre-KMC) and from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018 (post-KMC). The study proposal was duly approved by the hospital IRB. Data were gathered from the delivery book in the hospital delivery room, KMC logbook, and the patient’s chart in the Medical Records Section. Statistical analysis was done using descriptive statistics, chi-square test and Mann Whitney U test generated from SPSS version 20.0.

Results: There was a higher incidence of low birth weight infants in the pre-KMC period than in the post-KMC period. Preterm births account for approximately 2/3 of all low birth weights in both groups. More infants weighing < 1000 grams were born in the postKMC period. More infants in the post-KMC period stayed in the hospital longer (x2 = 58.67; df = 4; p < 0.001), have bigger discharge weights (x2 = 66; df = 4; p < 0.001), higher weight gain (p < 0.006) and improved outcome (x2 = 13.17; df = 2; p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in the proportion of infants according to cause of mortality between the two groups (x2 = 5.00; df = 4; p = 0.29).

Conclusion: Kangaroo mother care in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital results in higher proportion of infants who are discharged improved and with weights more than 2000 grams; however, infants who received KMC stay in the hospital longer than those infants who are not managed with KMC. The incidence of sepsis as the cause of death is not reduced by KMC.

Keywords: Low Birth Weight; Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital; Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC)

The birth weight of an infant is the first weight recorded after birth. The World Health Organization defined Low birth weight (LBW) as a birth weight less than 2500 grams [1]. This term has been used for a century since it was first proposed by Dr. Arvo Ylppö in 1919. He was a Finnish pediatrician who described a cohort of 2168 infants born in a German health facility between 1909 and 1918. While he provided no justification for this specific weight cutoff, it has become the global marker for low birth weight [2].

It is estimated that 15 - 20% of all births globally per year are low birth weight infants. This translates to > 20 million newborns worldwide, with over 95% of these infants born in low- and middle-income countries [3].

There is a considerable variation in the LBW rates across regions and within countries. There are marked global and regional variations in LBW rates. South Asia has the highest LBW rate of 28%, followed by Sub-Saharan Africa (13%), Latin America and Caribbean (9%), and East Asia and Pacific (6%) [3]. High-income regions report lower LBW rates, with UK reporting LBW rate of 6.9% [4] and US with 8% [5].

Low birth weight is a complex syndrome that includes preterm neonates, small-for-gestational age neonates at term, and the overlap between these two group. Each group has its own subgroup, with different causative factors and long-term effects, and distributions across populations that depend on the prevalence of the underlying causal factors [6-8].

Prematurity is defined as birth before completion of 37 weeks of gestation. It is one of the major causes of low birth weight deliveries. Annually, an estimated 15 million babies are born preterm. This accounts for 11.1% of all livebirths worldwide, and 60% of these were born in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa [9]. However, preterm births are a global problem since the high-income countries are also affected. In the US, >1 baby is born preterm for every 10 deliveries [10], and the country is even the 6th of 10 countries with the highest number of preterm births. In 2012, the Philippines ranked 8th of 10 countries with the highest number of preterm births. Locally, the study by Chavez., et al. reported that from 2015 to 2016, preterm births accounted for 65.02% of the low birth weight infants delivered and/or admitted to Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital [11].

What is frightening is that the incidence of preterm births is increasing. Possible reasons for this phenomenon are better measurement or reporting of preterm birth, increases in maternal age and underlying maternal health problems such as diabetes and hypertension, greater use of infertility treatments leading to increased multiple pregnancies, and changes in obstetric practices like more caesarian births before term [9]. However, the great majority of preterm births were found to be associated with no identifiable risk factor [12]. The lack of identifiable risk factor makes it difficult for health care physicians to prevent the occurrence of preterm birth. This unknown cause of preterm labor and birth has prompted the National Institutes of Health, as well as the March of Dimes and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to make preterm birth a priority [13].

Small-for-gestational age (SGA) babies are babies born with a birth weight less than the 10th centile for the age of gestation. This classification was developed in 1995 by an expert committee of the World Health Organization, and the definition is based on a birthweight-for-gestational-age measure compared to a gender-specific reference population [14,15]. Just like preterm birth rates, SGA rates also vary from one country to another. For instance, the USA has an SGA rate of 8.6% [16], while South Korea has an SGA rate of 11.4% [17]. Lee., et al. reported that in 2010, 32.4 million infants were born SGA in low-income and middle-income countries. India topped the 10 countries with highest SGA prevalence at 47%. The Philippines ranked 8th with an SGA prevalence of 33.6% [18]. In a recent study on Filipino infants conducted in Leyte, it was reported that the SGA prevalence was 22.9% [19]. That translates to > 2 babies born SGA for every 10 live births.

Various etiologies lead to the birth of an SGA infant but the most common etiology of SGA at birth is ‘placental insufficiency’ from various causes [20]. Other etiologies are genetic and chromosomal disorders, fetal malformation, congenital infections, and toxic substances like alcohol, cocaine, or smoking. Maternal diseases such as anemia and malnutrition may also affect fetal growth [21].

Preterm birth-SGA (PTB-SGA) is thought to be most pathological in terms of being due to placental dysfunction [22,23] and the adverse sequelae for the newborn infant [24,25]. These infants are 15 times more likely to die in the first month of life compared to infants born either preterm alone or SGA alone [24]. In 2010, the prevalence of PTB-SGA ranged from 1.2% in north Africa to 3% in southeast Asia [18]. Moreover, it was found out in the study conducted by Bartsch., et al. that there is a 1% prevalence of PTB-SGA in newborns born to immigrant Filipino mothers. They compared newborns born to immigrant women from five Asian countries, namely Vietnam, Philippines, China, Hongkong, and South Korea, and they found that the rate of PTB-SGA is 6.5 per 1000 infants born to immigrant Filipino women, 3.7 per 1000 infants born to immigrant Vietnamese women, and 2.3 per 1000 infants born to immigrant Chinese women. The relative risk (RR) of PTB-SGA was not higher for infants of mothers from Hongkong or South Korea [26].

The risk factors for PTB-SGA included maternal age >30 years, being firstborn, and short maternal stature; all of which appeared to carry a particularly strong risk (p < 0.05) [27]. Maternal age above 30 years has increased risk for congenital abnormalities and pregnancy comorbidities like hypertension and gestational diabetes that can increase the risk of PTB-SGA [28,29]. The association of being firstborn with PTB-SGA was thought to be due to commencement of antenatal care (ANC) since ANC started early in the first trimester may lead to early detection and management of pregnancy related health conditions and increased duration of standard pregnancy interventions like iron and folic acid supplementation [27]. PTB-SGA was also associated with maternal short stature since maternal short stature is an indicator of chronic malnutrition, thus there is a poor supply of nutrients to the fetus during gestation [27].

The problem of low birth weight is important because LBW is a valuable public health indicator of maternal health, nutrition, healthcare delivery, and poverty [30]. Neonates with low birth weight have > 20 times greater risk of dying than neonates with birth weight > 2500 grams [31,32]. Moreover, LBW is associated with long-term neurologic disability, impaired language development [33], impaired academic achievement, and increased risk of chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease and diabetes [30]. In addition, it has also been shown that reducing the burden of LBW would have important cost savings both to the health system and to households [34].

The majority of LBW is preventable by addressing the modifiable risk factors. It has been found that risk factors are interrelated and inequitably distributed within the population. Furthermore, exposure to one factor increases the likelihood of exposure to a constellation of factors, consequently increasing the risk. So that a change of approach is vital, from addressing individual risk factors with individuals in isolation, to addressing co-occurring groups of factors with the whole family, household and community around the women at risk [4].

The WHO’s recommendations on the care of the preterm and LBW focus on 3 areas: midwife-led continuity of care (MLCC), kangaroo mother care, and specific clinical interventions. Midwife-led continuity of care (MLCC) model is one where one midwife, or a group of midwives working together, provides care to a woman, her newborn and family throughout the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal continuum. MLCC has been associated with improved outcomes for the majority of women and babies at low risk of developing complications and has been shown to reduce the risk of prematurity by around 24%. This model requires a well-functioning midwifery program and should be provided by midwives who are educated, trained, licensed, and regulated, as well as access to emergency obstetric and neonatal care, either at the health facility or through transport to a referral center [35].

The specific clinical interventions recommended by WHO include interventions during pregnancy, labor, and newborn period that are aimed at improving outcomes for preterm and LBW infants. The guidelines include antenatal steroids, prophylactic antibiotics for premature rupture of membranes, magnesium sulfate to prevent future neurological impairment of the child, thermal care for the neonate, kangaroo mother care, exclusive breastfeeding, feeding support, safe oxygen use, and other treatments to help babies breathe more easily [35].

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) of preterm and LBW infants, particularly those weighing < 2 kg. It includes exclusive and frequent breastfeeding in addition to skin-to-skin contact and support for the mother-infant dyad. It has been shown to reduce mortality in hospital-based studies in low- and middle-income countries [35].

Tracing the history of kangaroo mother care (KMC) reveals that first studies on “early contact” with mother and baby at birth were described by Peter de Chateau in Sweden on 1976; however, the articles did not specifically describe that this was skin-to-skin contact [36]. A similar work was performed in the USA by Klaus and Kennel, and was more well known in the context of early maternalinfant bonding. Thomson subsequently first reported the use of the term “skin-to-skin contact” in 1979 and quoted the work of de Chateau in its rationale [37]. However, the concept of Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) was made more widely known when it was first introduced and implemented in Bogota, Colombia.

In 1978, Dr. Edgar Rey Sanabria, a professor of Neonatology of the Department of Paediatry of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, introduced a method to alleviate the shortage of caregivers and lack of resources. This was in response to increasing morbidity and mortality rates in the Instituto Materno Infantil NICU in Bogota, Colombia. He suggested that mothers have continuous skin-toskin contact with their LBW to keep them warm and to breastfeed them exclusively, freeing in turn overcrowded incubator space and care givers. Another element that was introduced was early discharge in the kangaroo position despite prematurity [38].

Dr. Rey and Dr. Martinez published their results in 1981 in Spanish and used the term “kangaroo mother method”. This was brought to the attention of English speaking health professionals in an article by Whitelaw and Sleath in 1985 [39].

The key features of KMC are early, continuous and prolonged skin-to-skin contact between the mother and the baby; exclusive breastfeeding; initiated in the hospital and can be continued at home; early discharge of small babies; adequate support of mothers at home and follow-up and gentle effective method that avoids the agitation routinely experienced in a busy ward with preterm infants [40].

Since then, KMC has been shown by several studies to improve survival rates of premature and LBW newborns, lower the risks of nosocomial infection, severe illness, and lower respiratory tract disease, increase the rate of and lengthen the duration of exclusive breastfeeding, as well as improve maternal satisfaction and confidence [41-45]. Research and experience have shown that KMC is at least equivalent to conventional care or the incubators in terms of safety and thermal protection, if measured by mortality. KMC has also been shown to offer noticeable advantages in cases of severe morbidity by facilitating breastfeeding. It also contributes to the humanization of neonatal care and to better bonding between mother and baby in both low- and high-income countries [46,47]. As such, KMC is a modern method of care in any setting, even where expensive technology and adequate care are available [40].

Kangaroo mother care spread to the Philippines in 1999 when Dr. Socorro Mendoza, after training on KMC at Fundacion Canguro in Colombia, piloted the program at Dr. Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital in Manila. After 1 year, KMC was institutionalized and adopted as the standard policy of care for all LBWs and was cascaded to the local Manila Health Department that covered all lying-in clinics in 2004. Subsequently, the Manila city health office adopted the technique as its standard of care for all LBWs and effectively established its network with the pioneer Fabella center. In 2006, per recommendation by the Colombian KMC Foundation, a KMC database encoding system was initiated [48].

Upon Dr. Mendoza’s retirement from service in 2008, she established the Bless-Tetada (BT-KMC) KMC Foundation with the goal of providing impetus for the faster development of KMC nationwide. Standardization of protocols and procedures for training, implementation, research, monitoring and accreditation were developed. The first hospital that underwent training, pilot implementation, and accreditation as KMC Center of Excellence was Mariano Marcos Memorial Medical Center in Region 1. This occurred in 2010 to 2011, a good 11 years from the start of KMC in the Philippines.

Then the Eastern Visayas Regional Medical Center in Iloilo became the second KMC Center of Excellence in 2012. Since then, several hospitals are in the thick of pilot implementation. The BT-KMC Foundation remained in partnership with Fabella center, providing data banking services, quality improvement activities, as well as research and training [48].

The KMC experience in Fabella has shown significant benefits to all stakeholders. The risk of mortality among LBWs in KMC has significantly and consistently been shown to be lower. Deaths due to sepsis dropped from 34% to 24%. Breastfeeding rates were significantly higher up to 5 months post discharge. These translated to a drop in hospital stay by 50% and a savings of around 75% of hospital cost. Improvements in hospital resource utilization were also evident, such as personal efficiency, nurse: patient ratio, reduced budget for medications, and zero child abandonment [48].

Bohol soon hitched onto the KMC bandwagon in 2014 after Dr. Socorro Mendoza, offered training in KMC to the staff of Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital (GCGMH). The offer was made under the assumption that more LBWs would be delivered by mothers whose prenatal health was compromised after the 7.2-magnitude earthquake hit the island in 2013. The hospital responded by sending a group of healthcare providers lead by Dr. Maribeth Jimenez. Consequently, the KMC program was established in GCGMH and formal implementation was launched. Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital soon became a KMC Center of Excellence in 2015.

Dr. Chavez, a resident trainee in the Department of Pediatrics of GCGMH, conducted a study on KMC experience for the 2 years after the launching of KMC in the hospital. In his study, he reported that GCGMH has a LBW incidence of 4.5%, 65% of these were preterm, and the remaining 35% were fullterm. He also reported that there was a very high enrolment rate ranging from 98% to 99%, and that the sole reason for non-enrolment was death of the newborn. The cause of mortality was reported to be sepsis. Hospital stay of the majority of these LBWs was 7 days or less, and the weight gain in g/kg was 45 g/kg and more [11].

Inasmuch as the Dr. Chavez’s study dealt more with the experience of KMC in the hospital including the challenges that were met during implementation, he recommended that a study on the impact of KMC on the variables of morbidity and mortality among LBW infants be conducted [11]. Hence, this study was borne.

This research paper is believed to benefit the following stakeholders:

To determine the effect of kangaroo mother care (KMC) on the morbidity and mortality of low birth weight babies admitted in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital.

Study design: This is a descriptive retrospective study.

Study population and locale: This study included all neonates with birth weights < 2000 grams admitted to the neonatal and pediatric wards of Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital.

Duration of the study: This study included eligible neonates born from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013 as the pre-KMC group, and neonates born from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018 as the post-KMC group.

Sampling technique: This study utilized total population sampling.

All low birth weight infants admitted to the neonatal and pediatric wards of Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital. The post-KMC group will include all neonates enrolled to the KMC program.

In as much as all qualified neonates for KMC enrolment will comprise the post-KMC group, the following exclusion criteria will apply for the subjects under pre-KMC group:

An approval of the proposal was sought from the hospital institutional review board (IRB).

After IRB approval of the proposal was obtained, a letter was written to the hospital medical center chief through the IRB to ask permission to access the records of all patients eligible for inclusion in the study. A similar letter-request was also written to the hospital KMC coordinator, Dr. Maribeth M. Jimenez. A waiver of informed consent was also duly filed and signed.

Once permission was granted, the pertinent data were gathered from the logbook of all deliveries in the hospital delivery room, KMC logbook, and the patients’ charts in the Medical Record Section. A research assistant was hired to help in the data gathering.

The data that were gathered were noted and tabulated. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics like frequency and percentage distribution tables for categorical variables and measures of central tendency for continuous variables. Chi-square test and Mann Whitney U test were used to determine for significant difference among the different variables before and after the KMC program was established. Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test and Mann Whitney U test were generated using SPSS version 20.0.

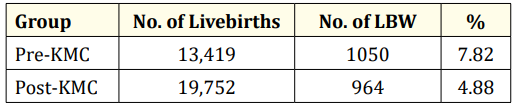

There were 1050 cases of LBW babies out of 13,419 deliveries in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital from 2010 to 2013, and 964 cases of LBW babies out of 19,752 deliveries from 2015 to 2018.

Table 1: Incidence rate of low birth weight infants pre-KMC and post-KMC.

Table 1 shows the incidence rate of LBW infants admitted to Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital before and after the KMC program was introduced. This shows that the incidence rate of LBW is higher during the pre-KMC period.

Of the 1050 cases of LBW babies in the pre-KMC period, and out of the 964 LBW babies in the post-KMC period, only 549 infants in the pre-KMC period and 867 infants in the post-KMC period were eligible for inclusion in the study.

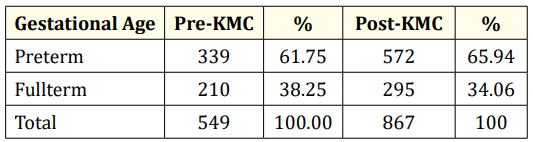

Table 2: Gestational age of low birth weight infants admitted to GCGMH. p = 0.11 (Not significant).

Table 2 shows the gestational age of LBW infants included in the study. In both pre-KMC and post-KMC periods, preterm infants account for roughly 2/3 of the low birthweight infants. The remaining number of infants were fullterm. Comparative analysis showed that there is no significant difference in the incidence of preterm and fullterm neonates before and after the KMC program was established (p = 0.11) (Table 3).

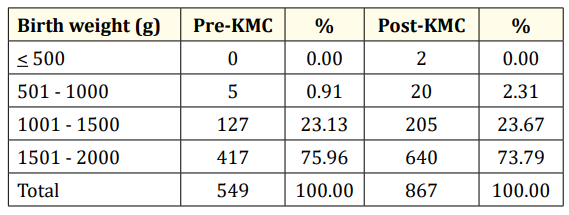

Table 3: Birth weights of LBW infants admitted to GCGMH. p = 0.156 (Not significant).

The birth weights of LBW infants are shown in table 3. There were 2 infants weighing 500 grams and lower who were admitted in the post-KMC period. Moreover, considerably more infants weighing 501 to 1000 grams were admitted in the post-KMC period. There were similar proportions of infants weighing 1001 to 2000 grams who were admitted in both pre-KMC and post-KMC periods. Over all, there is no significant difference in the birthweights of neonates delivered before and after the KMC program was established in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital (p = 0.156).

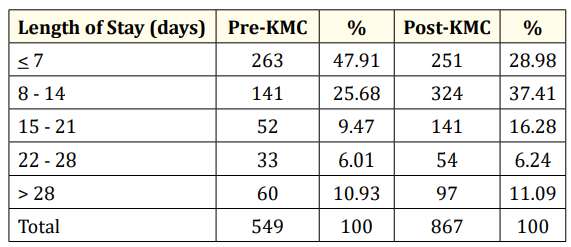

Table 4: Length of hospital stay of LBW infants admitted to GCGMH.

Table 4 show the length of hospital stay of the low birth weight infants. A greater proportion of infants in the pre-KMC period stayed for 7 days or shorter compared to that in post-KMC period. Conversely, more infants in the post-KMC period stayed in the hospital for 8 days to 21 days compared to that in the pre-KMC period. The proportion of infants who stayed in the hospital for 22 days and longer is relatively similar in both pre-KMC and post-KMC periods.

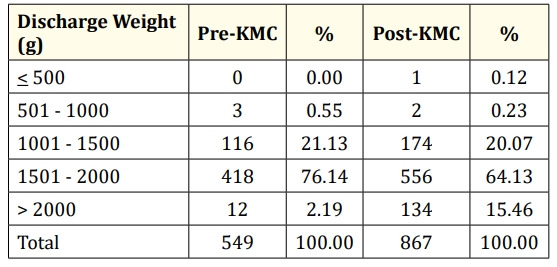

Table 5: Discharge weight of LBW infants admitted to GCGMH.

The discharge weights of the low birth weight infants are shown in table 5. There were more infants in the pre-KMC period who were discharged with weights between 1001 and 2000 grams; but there was a greater proportion of infants in the post-KMC period who were discharged with weights more than 2000 grams (15.47% vs 2.19%).

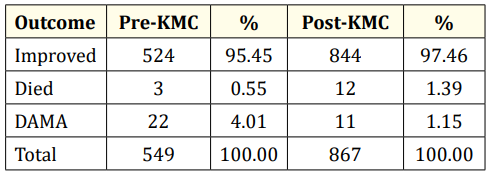

Table 6: Outcome of LBW infants admitted to GCGMH.

Table 6 shows the outcome of low birth weight infants. Majority of the infants were discharged improved in both pre-KMC and post-KMC periods. There was a higher proportion of infants who died in the post-KMC period, but there were more infants in the pre-KMC period who were discharged against medical advice.

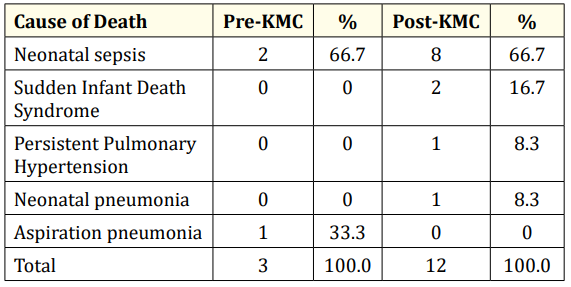

Table 7: Causes of mortality of LBW infants admitted to GCGMH.

The causes of deaths in low birth weight infants are listed in table 7. Neonatal sepsis topped the list in both pre-KMC and postKMC periods. Aspiration pneumonia caused a mortality in the preKMC period. Sudden infant death syndrome, persistent pulmonary hypertension and neonatal pneumonia accounted for the remaining deaths in the post-KMC period.

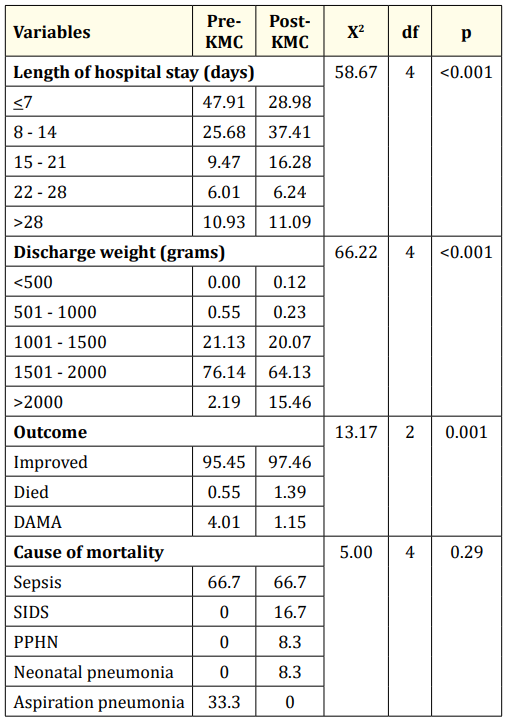

Table 8 shows the comparison of the different variables before and after the KMC program was established. Using chi-square at 0.05 level, there was a significant difference noted in the proportion of infants according to length of stay (x2 = 58.67; df = 4; p < 0.001). There was a significantly higher proportion of infants in the post-KMC period who stayed in the hospital longer than those in the pre-KMC period. There was also a significant difference noted in the proportion of infants according to the discharge weights (x2 = 66; df = 4; p < 0.001). A significantly higher proportion of infants in the post-KMC period weighed >2000 grams than those in the pre-KMC period. There was also a significant difference noted in the proportion of infants according to outcome (x2 = 13.17; df = 2; p = 0.001). A significantly higher proportion of infants in the postKMC period had improved outcome than those in the pre-KMC period (97.46% vs 95.45%). More infants in the pre-KMC period went on DAMA compared to those in the post-KMC period (4.01% vs 1.15%). There was no significant difference noted in the proportion of infants according to the cause of death between the two groups (x2 = 5.00; df = 4; p = 0.29).

Table 8: Comparison of the different variables before and after the KMC program was established.

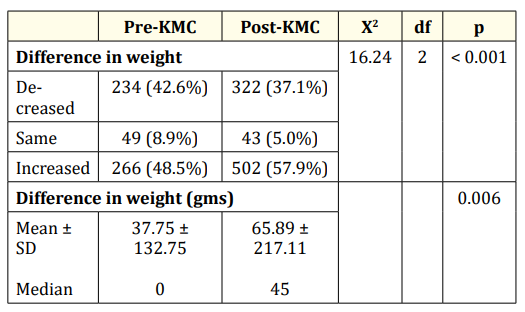

Table 9: Comparison of the difference in weight before and after the KMC program was established. Mann Whitney U test.

Table 9 shows the results of the subset analysis on the difference in weight before and after the KMC program was established. This was computed using the formula: discharge weight - birthweight. Using chi-square at 0.05 level, there was a significant difference noted in the proportion of infants with decreased, same or increased weight (x2 = 16.24; df = 2; p < 0.001) between the two groups. Significantly higher proportion of infants in the post-KMC period had increased weight than those in the pre-KMC period. When the median difference in weight was compared, there was also a significant difference noted as shown by the p value of 0.006 derived from the Mann Whitney U test. The increase in weight of infants in the post-KMC period was significantly higher than those in the pre-KMC period.

Kangaroo mother care has been shown by several studies to provide significant benefits to the low birth weight infants. One of these benefits is the reduction in the length of hospital stay by 50% [48]. This study however showed that a significantly higher proportion of infants in the post-KMC period stayed longer in the hospital compared to those infants in the pre-KMC period. The authors could think of several factors that may contribute to this phenomenon. One is that the desired weight or the desired weight gain per day may not be attained at the soonest possible time. This may be because of less than the ideal duration of mother-and-baby contact. Unlike Fabella Hospital where the KMC program has been institutionalized and where there is a dedicated ward for Kangaroo Mother Care, our hospital does not have a ward dedicated for the KMC mother and baby dyad. What we have is a breastfeeding room cum kangaroo mother care room with reclining chairs where the mother could breastfeed her infant and do skin-to-skin contact at the same time. As such, the kangaroo mother care could not be performed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week which is the ideal. Another possible reason for the apparently higher proportion of infants in the post-KMC period who stayed longer in the hospital is the higher number of patients in the pre-KMC period who were discharged against medical advice. Chavez., et al. reported in his study that the primary reasons for DAMA are longer hospital stay, financial constraints, and uncomfortable environment. He further reported that longer hospital stay and financial constraints may be interrelated since bigger source of funding may be needed for a longer hospital [11]. Unfortunately, majority of the patients that the hospital takes care of are patients below poverty line.

This study showed that a significantly higher proportion of infants in the post-KMC period was discharged with weights > 2000 grams compared to infants in the pre-KMC period. The authors could not find other studies that reported the weights on discharge of infants managed by KMC; however, the subset analysis showed that more infants in the post-KMC period have increased weight and that the increase in the weight is significantly higher than in infants before KMC was established. This better weight gain has also been previously shown by several studies. In 2001, Ramanathan., et al. reported that infants in the KMC group demonstrated higher weight gain (15.9 + 4.5 gm/day) compared to infants in the control group (10.6 + 4.5 gm/day) [49]. Recently, Ramesh and Sundari also reported that infants who received KMC have higher weight gain compared to infants who received conventional neonatal care (21.11 + 2.8 gm/day vs 15.61 + 2.6 gm/day) [50].

Analysis of the outcome of infants before and after the KMC program was established in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital shows that a significant proportion of infants in the post-KMC period was discharged improved compared to infants in the preKMC period. This finding may be indirectly related to the higher proportion of infants in the pre-KMC period who were discharged against advice. In the same way, the mortality rate in the pre-KMC period may not be reflective of the true mortality rate in that period because of the higher proportion of infants who were discharged against medical advice. The implication of this finding is that with the KMC program in place, and probably with proper education of the parents about the program, LBW infants are now able to receive the ideal management and are discharged only when they are seen fit for discharge.

Kangaroo mother care has frequently been reported to lower the risk of sepsis in low birth weight infants. In a recent study by Habib., et al. in rural Pakistan, it was reported that infants who received KMC on top of essential neonatal care and chlorhexidine had a lower risk of infections (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.27 - 0.63) compared to those who received only essential neonatal care and chlorhexidine only or essential neonatal care alone [51]. The risk for severe infection or sepsis has also been shown to be reduced in infants who received KMC in a Cochrane systematic review in 2016 (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.36 - 0.69; eight trials, 1464 infants; moderate-quality evidence) [52]. However, this study shows that there is no significant difference in the incidence of neonatal sepsis as the cause of death in both pre-KMC and post-KMC groups. The authors could only theorize that the lack of a dedicated ward for KMC may be the reason why there is no significant difference in the rate of sepsis between the two groups. Infants before and after KMC was established are accommodated in the special care unit of the NICU complex and are attended to by healthcare staff who also attend to severely ill patients in the NICU.

Kangaroo mother care in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital results in higher proportion of infants who are discharged improved and with weights more than 2000 grams; however, infants who receive KMC stay in the hospital longer than those infants who are not managed with KMC. The incidence of sepsis as the cause of death is not reduced by KMC.

The authors would like to strengthen the recommendation previously made by Chavez., et al. to provide a ward dedicated for KMC. The ward should be big enough to accommodate the mother and baby dyad and comfortable and private enough for the conduct of skin to skin contact and breastfeeding. Both mothers and babies should be attended to by healthcare staff separate from the NICU staff. By this way, full KMC is implemented and hopefully will result in shorter hospital stay and reduced rate of infections.

Copyright: © 2021 Anabella S Oncog., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.