Ednaldo de Jesus Filho1, Tatiana Frederico de Almeida2, Sandra Garrido de Barros2, Maria Isabel Pereira Vianna2 and Maria Cristina Teixeira Cangussu2*

1Doctorade Student in Dental Health in Federal University of Bahia, School of Dentistry/UFBA, Brazil

2Professor in School of Dentistry/UFBA, Araújo Pinho Avenue, Brazil

*Corresponding Author: Cristina Teixeira Cangussu, Professor in School of Dentistry/UFBA, Araújo Pinho Avenue, Brazil.

Received: February 04, 2021; Published: March 24, 2021

Citation: Ednaldo de Jesus Filho., et al. “Socioeconomic and Behavioral Conditions, Acess and Use of Dental Health Services by People with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the City of Salvador, BA, Brazil”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 4.4 (2021): 57-65.

Aim: To characterize the socioeconomic, behavioral status, acess and use conditions of dental care services of people with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) living in Salvador.

Methods: This is a descriptive observational cross- sectional study. A sample of 70 caregivers of people with ASD was recruited from two Child Psychosocial Assistencial Centers (CAPSi) and in a special Educational Service Center (Pestalozzi Bahia) in the city of Salvador, state of Bahia, Brazil in 2019. Caregivers were interviewed individually by the principal researcher. Data collection was typed in the Excel®. Then, a descriptive analysis of the variables was performed in MINITAB 17.

Results: Mothers were the main caregivers of people with ASD (88.4%). The majority (69,12%) stated that found it difficult to provide dental care. Unsuccessful appointment scheduling was the barrier most highlighted by caregivers (52,12%). Among people with ASD, only 21.43% would be independent for oral hygiene actions. Some factors were uncomfortable, such as noise (71.43%) and a light source (67.14%). On the other hand, the white coat generated discomfort in only 38.57%.

Conclusions: Most people with ASD had difficulties in accessing public dental care. Although oral problems are not so different from people with typical development, people with ASD must take a different approach. In the city of Salvador is necessary to structure and publicize public places for dental care of people with ASD. Public dental services must be able to welcome and extend the care and guidance to those caregiver for people with ASD.

Keywords: Dental Health; Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD); Salvador

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a life-long heterogeneous psychiatric disorder, characterised by impairments in communication and social relationships and by a narrow, repetitive and stereotyped repertoire of activities, behaviours as well as restricted interests. Children with autism often have nutritional problems A number of studies have been made of mealtime behavioral problems and food selectivity and early initiation of special education appears effective in preventing these conditions [1]. Patients who have autism frequently also have allergies, immune system problems, gastrointestinal disturbances and seizures. So, dental health care workers must be aware of all conditions to provide optimal care to the children with autism spectrum disorders [2].

These features have an impact on the oral health of these individuals: high risk of dental caries, poorer periodontal status, and bruxism are often described. Children with ASD often provide limited collaboration with medical procedures, particularly those considered invasive such as dental care [2,3]. Children with ASD are at higher risk of alterations of the oral microbiota and increased risk of traumatic injuries too. Because it is a haeterogeneous disease with a wide range of expressions in individuals, adapted and specific strategies are needed, they represent a challenge for the dental community [4]. For example, Garcia., et al. [1] had identified food rejection and limited food variety were associated to an increased prevalence of malocclusion and altered Community Periodontal Index scores in children with ASD.

In the other hand, Lam., et al. [5], when comparing salivary flow rate, tooth decay, gum diseases, tooth malalignment and tooth trauma, no significant differences were found between children and adolescents diagnosed with and without ASD. The findings did not suggest ASD as a predisposing factor to oral diseases: other factors including sugary diet and inadequate oral hygiene may play a more important role.

Children with ASD are prone to agitation, self-injury, and emotional dysregulation; they can also present hypersensitivity to sensory input. These features make it difficult for professionals to examine and treat children with ASD and most of them are treated under general anesthesia or sedation; they interfere with dental care and constitute a barrier to it [3]. Although children with autism apply for dental services, the rate for these children receiving dental services is considerably low and most of the services rendered are tooth extractions [6]. Instead of this, Du., et al. [7] related that parents of children with ASD had higher scores in dental knowledge and attitudes than those without ASD and children with ASD had less frequently performed tooth-brushing and used toothpaste, but more often required parental assistance in toothbrushing.

Using data from the 2005-2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) we compared children with autism spectrum disorder with children with special health care needs with other emotional, developmental or behavioral problems (excluding autism spectrum disorder) and with other children with special health care needs. unmet need for each service type among CSHCN ranged from 2.5% for routine preventive care to 15% for mental health services. Autism in children provider characteristics pose barriers to accessing care [8].

Oral health is important to physical and psychological health. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience significant oral care challenges, but there were few research that examines efficacious interventions to improve care [9].

Dental professionals caring for patients with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) will need to provide oral health care based on a family-centered approach that involves a comprehensive understanding of parental concerns and preferences, as well as the unique medical management, behaviors, and needs of the individual patient [10]. Dental management of an autistic child requires in-depth understanding of the background of the autism and available behavioural guidance theories. The dental professional should be flexible to modify the treatment approach according to the individual patient needs [11].

Different tools and techniques of evidence-based practice can be considered: visual pedagogy, behavioral approaches, and numeric devices can be used. 3 Feasibility of conducting oral health services like a screening in preschool children with ASDs was associated with their cognitive functioning, social skills development, communication skills development, reading skills and challenging behaviours [7].

Thus, the aim of this study was to characterize the socioeconomic, behavioral status, acess and use conditions of dental health services of people with ASD living in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

This is a descriptive observational cross- sectional study, involving people diagnosed with ASD, who attend health and education references units in the city of Salvador, state of Bahia, Brazil in 2019. Data collection was developed in two Child Psychosocial Assistencial Centers (CAPSi) and in a special Educational Service Center (Pestalozzi Bahia). The caregivers of people with ASD were interviewed individually by the principal researcher in the institutions mentioned.

Table 1: Description of the variables used in the study. *minimum wage in Brazil ( ±U$200).

Data were typed in the Excel®. Then, a descriptive analysis of the variables was performed in MINITAB versão 17, obtaining simple and relative frequencies and their categories. All procedures adopted followed laws of Ethics Research and welfare human beings in order to avoid procedures that may pode risks to the dignity of patients or guardiansmay (CAAE register number: 18305119.4.0000.5024).

Seventy people were interviewed in the three institutions. Fifty- three in Pestalozzi Bahia, fourteen in CAPSi (Itapoan district) and three in CAPSi (Liberdade district). Mothers were the main caregivers of people with ASD (88.4%) and most of the had completed high school (55.07%), with familiar income up of 01 Brazilian minimum wage (±US 200). They received some government incentive (56.52%) and used public health services exclusively (71.43%) (Table 1).

Regarding acess and use of dental health services, a regular visit to the dentist was not a reality for a large part of the respondents (57.14%), but 81.82% said that they have already received guidance in oral health. The diagnosis of the person with ASD was made after 03 years of age (57.14%) and 65.22% of the caregivers did not know any place for dental care of these people by the public system in the city. Still in this context, 69.12% said they found it difficult to provide dental care, with the unsuccessful appointment scheduling being the barrier most highlighted by caregivers (52.13%) (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the experience of people with ASD according to the observation of their parents. In all of them, 72.46% had already gone to the dentist, but 57.14% did not go to the dentist in the last year period that preceded this study. Most did not perform any procedure (52.86%), nor did they receive local (85.79%), general anesthesia (n = 54; 79.41%), sedation (68.12%), or needed to be physically restrained (61.49%). With regard to the behavior of people with ASD for daily activities and oral hygiene, Figure 1 reveals that only 15.94% of those caregiver consider those people to be independent for daily activities, while 21.43% would be independent for oral hygiene actions.

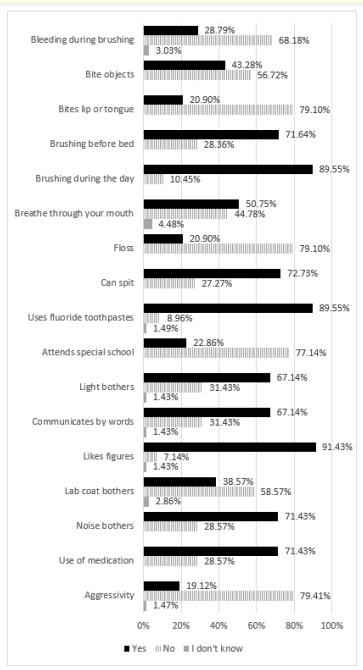

People with ASD were not aggressive towards strangers (79.41%), 22.86% of them studied at a special school and 71.43 used medication regularly. Some factors were uncomfortable, such as noise (71.43%) and a light source (67.14%). On the other hand, the professional costume generated discomfort in only 38.57% of people with the disorder (Figure 2).

Table 2: Socioeconomic characteristics of the study sample.

Table 3: Characteristics of acess and use of dental health services for people with ASD in Salvador, Ba, 2019 (n = 70). * Information lost or not given.

Figure 1: Behaviours of the person with ASD in Salvador- BA, 2019 (n = 70).

Most people with ASD liked pictures and illustrations (91.43%) and were able to communicate through words (67.14%). Toothbrushing during the day was performed by 89.55% of them. Gingival bleeding was observed during brushing in 68.18% of the sample. The fluoride paste was used by 89.55% of these people, with 72.73% being able to spit. The use of dental floss was not common in 79.10% of the sample. It was also reported that most people with ASD in this study were not in the habit of biting objects or bringing them to the mouth (56.72%), or of biting the lip or tongue (79.10%). Oral breathing was reported by 50.75% of those caregiver (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Behavioral characteristics of the study sample. Salvador-BA, 2019 (n = 70).

This work highlighted the socioeconomic and behavioral characteristics of people with ASD in the city of Salvador-BA, as well as the reality of access and use of dental care services. In the studied sample, it was observed that the mother was the main caregiver, a result similar to that found by Schmidt and Bosa [12] and Christmann., et al. [13] The low level of education of the caregivers and the low family income observed among the participants in this study can have an impact on their oral health. Educational level and family income are indicators that can interfere with the quality of oral health care [7,14].

In addition, access to health services in Brazil is strongly influenced by the social condition of people and the place where they live. 15 The late diagnosis of ASD (after 3 years of age) identified in this study has an important impact on the care and development of individuals. The pediatrician's role is fundamental to the child's health with ASD since they can intervene and direct this child to a specialist in early life, increasing the acceptance and effectiveness of the treatment and allowing the creation of an early bond with the professionals involved, who will be able to approach correctly, ensure prophylactic therapies and adequate care [4].

The peculiar behaviors of people with ASD have an impact on their oral health. They collaborate little with their own oral hygiene [4]. In this study, the minority of people evaluated was independent to carry out daily activities (15.94%), including oral hygiene (21.43%). Most of the people with ASD in this study used medications regularly, both to control anxiety and other comorbidities. The tooth rash in some children with this disorder can be delayed due to gingival hypertrophy caused by the use of phenytoin, an anti-epileptic medication.

Dental lesions are common in people with ASD, in addition to an increased tendency to some occlusal disorders, such as ogival palate, crowding and open bite. Harmful oral habits, such as nocturnal bruxism, protrusion of the tongue and bite on the lips and gums, can be observed among them [11], and those caregiver have reported the presence of these habits in the evaluated group. The early diagnosis of ASD is also advantageous in this sense since the necessary education, as well as social, communication and behavioral approaches can be started early with a positive effect on the elimination of bruxism and its consequences [6].

Regarding the habit of tooth brushing, those caregiver stated that 10.45% of people with ASD did not brush during the day and that 28.36% did not brush before sleeping. A recent study conducted in Israel showed that around 25% of children with ASD assessed also did not brush during the day [16]. In the study by Du., et al. [18] a lower brushing frequency was observed, as well as a lower use of toothpaste. According to these authors, this can be attributed to low cognitive functioning and oral hypersensitivity.

In the present study, gingival bleeding observed during tooth brushing, an alteration strongly related to oral hygiene, was not commonly reported by those caregiver. The literature reports that the presence of biofilm is considerably higher in children with this disorder [17]. According to Lam., et al. [5], with the exception of bruxism, children and adolescents with ASD appear to be no longer susceptible to oral diseases such as caries, periodontal diseases, dental trauma and malocclusions, but are more exposed to the risk factors of these problems, such as difficulty in performing oral hygiene. and a tendency to a cariogenic diet. However, in this research, no clinical examination was performed to check the biofilm, nor a thorough evaluation of the diet.

Most of the people interviewed reported that people with ASD with whom they lived used fluoride paste and knew how to spit, although flossing was not a reality. On a study by Du., et al. [18] in Hong Kong, highlighted that parents of people with ASD reported not using toothpaste due to intense salivation during brushing. Parents of children with ASD who eat toothpaste or oral rinses, or who are unable to wash their mouths and spit after toothbrushing have real concerns about gastrointestinal irritations and dental fluorosis [19].

It is known that fluoride is a gastrointestinal irritant that can cause abdominal discomfort and vomiting when ingested in excessive amounts. Prolonged ingestion can damage the gastroduodenal mucosa and develop fluorosis in the permanent dentition [19]. However, fluorides are fundamental for the process of remineralization of tooth enamel exposed to acidity in the oral cavity and the prevention of tooth decay in the current context. The dentist must be attentive and inform caregivers about the importance of the rational and appropriate use of these substances [2].

According to the findings of this study, most people with ASD liked pictures and illustrations and were able to communicate using words. They were generally not aggressive towards strangers and the white coat did not bother as much as the light and noise. All of these aspects must be taken into account when preparing the person with the disorder for dental care.

Cognitive deficits, difficulty in communication, social interaction and reading, in addition to unexpected behaviors, are associated with the ability to cooperate or not with dental evaluation. This justifies the importance of knowing the profile of the person with ASD who will undergo dental treatment.

Children with ASD present a challenge for the dental community, requiring specific and adapted strategies to allow them to overcome the barriers of dental care. Different tools and techniques of evidence-based practice can be considered: visual pedagogy, behavioral approaches and numerical devices can be used [3]. Parents and dental professionals agree on the importance of preparing the person with ASD before going to a dental appointment [18,20]. At home, the actions are aimed at practicing activities that simulate what happens during the visit to the dentist, watching videos, reading books, seeing pictures and step-by-step lists about oral hygiene.

In the office, the preparation is focused on the child's repeated desensitization consultations [9]. Dental professionals are probably one of the most in contact with people with ASD during their professional practice. Therefore, they need to be familiar with the medical and dental treatment of this group of special patients. A thorough approach, centered on that family's experience and experiences, the parents' complaints, the child's challenging behaviors and related comorbidities can generate mutual trust between parents and professionals, since the close relationship between parents, professionals and patients with ASD will most likely produce the best therapeutic decisions [10].

Caregivers' perceptions about dental treatment were analyzed, among other aspects, based on the report of their experiences to locate a willing and trained dentist, to have access to the service when necessary and the waiting time for the person with ASD to be attended. Most caregivers reported not making regular visits to the dental office, although they claim to have received guidance on health and oral hygiene. The lack of knowledge about oral health and the little importance given to deciduous teeth, in addition to the fears and myths created by the caregivers themselves regarding dental treatment create barriers for preventive and early treatment for people with ASD [20].

In this investigation, most people with ASD had access to the dental office (72.46%), even though the consultation took place over a period of more than one year (57.14%). In the study by Chiri and Warfield 8 children with ASD were significantly at greater risk of not receiving the necessary dental care. People with ASD are usually treated with general anesthesia or sedation [3]. In this work, this was not a common practice. Currently, it is known that the risk of using nitrous oxide is minimal, if not non-existent. If caregivers are strongly opposed to the use of this substance, the dentist should suggest another type of sedation, if necessary [21].

With regard to the patient with a disability, in Brazil it is recommended that services should be organized to offer priority care within the scope of primary care, and there should be specialized and hospital referral units for the most complex cases and those that need assistance. care under general anesthesia [22]. In this study it was found that most caregivers did not know any place for public dental care for people with ASD in the city. Those caregiver who knew, reported difficulties to access the service, alleging, mainly, a difficulty in making an appointment. The locations for dental care for people with ASD by SUS in the city of Salvador are known to only 31.88% of the caregivers interviewed. This study obtained important information about access and treatment of ASD in Salvador, Bahia, including oral health, information relevant to the planning of health services for this group. It is worth mentioning that this is a limited sample size, and that it may not reflect the reality of the universe of patients seen in the city or elsewhere in Brazil.

Families that make exclusive use of the public dental care sector were the majority in the sample of this study, as well as the late diagnosis of ASD. Most people with ASD had unfavorable socioeconomic conditions, such as caregivers' education level and low family income. Favorable oral hygiene habits were reported by most respondents, however the use of dental floss is still rare among them. Other oral habits were verified, such as biting objects and tongue and these behaviors need to be considered when planning the treatment of these patients.

Difficulties in accessing dental care and limits on care provided, such as lack of sedation and general anesthesia, were also verified in this research. The sooner the diagnosis of ASD is made and the bond with a dental professional the better it will be for the patient and his family. Although oral problems are not so different from people with typical development, the person with ASD must take a different approach. It is necessary to structure and publicize public places for dental care for people with ASD in the city of Salvador, and they need to be able not only to welcome, but also to extend the care and guidance to those caregiver for providing quality oral health care.

Copyright: © 2021 Ednaldo de Jesus Filho., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.