Daniel López H1* and Jessica Franco F2

1

Pediatrician, Pediatric Service of the Hospital San Juan de Dios Curicó, Curicó,

Chile

2 Pediatric Gastroenterologist, Pediatric Service of the Hospital San Juan de Dios

Curicó, Curicó, Chile

*Corresponding Author: Daniel López H, Pediatrician, Pediatric Service of the Hospital San Juan de Dios Curicó, Curicó, Chile.

Received: February 03, 2021; Published: March 24, 2021

Citation: Daniel López H and Jessica Franco F. “Trichobezoar Intestinal Obstruction: Rapunzel Syndrome”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 4.4 (2021): 44-48.

Rapunzel syndrome is a rare condition, more frequently found in young females and associated with trichotillomania, trichophagia and psychiatric disorders. It is due to the development of a trichobezoar composed of hair, located in the stomach and extending into the duodenum. We present a case of a 16-year-old female adolescent with a history of depression and trichotillomania; with regurgitation, heartburn and epigastralgia of 3 months of evolution, and recent vomiting, associated with a mass in the epigastrium extending to the left hypochondrium, adherent to a deep plane, painful on palpation. Upper gastrointestinal series with barium was compatible with bezoar and confirmed with an upper endoscopy where hair occupying the stomach up to the pylorus and duodenal bulb was evidenced, consistent with gastroduodenal trichobezoar. Laparotomy was performed and the trichobezoar was extracted from the entire gastric chamber and pylorus without complications, and the patient remains in control with psychotherapy. The objective of this work was to demonstrate that upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and laparotomy are the diagnostic and treatment methods of choice, respectively, in Rapunzel Syndrome.

Keywords: Intestinal Obstruction; Trichobezoar; Trichophagia; Depression; Rapunzel Syndrome

ADHD: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; cm: Centimeter; EDA: Upper Digestive Endoscopy; fl: Femtoliter; g/dl: Grams Per Deciliters; mg/dl: Milligrams Per Deciliters; mEq/l: Mileequivalents Per Liter; mU/L: Milliunits Per Liter; ng/dl: Nanograms Per Deciliter; pg: Picogram; Upper GI: Upper Gastrointestinal Tract; ul: Microliters

A gastric bezoar is a solid mass resulting from the ingestion and accumulation of any material, partially digested or not, and that generally remains in the stomach. They can be classified into: 1. Phytobezoars, the most common type of bezoar, composed of plant matter; 2. Trichobezoars, composed of hair; 3. Pharmacobezoars: compounds of ingested drugs; Others - Composed of a variety of other substances (for example: tissue paper, rubber, shellac, mushrooms, styrofoam cups, cement, and vinyl gloves) [1]. A rare form of trichobezoar is known as Rapunzel syndrome, a pathological condition that occurs in people with trichophagia where the bezoar is located in the stomach and may extend through the pylorus reaching the duodenum or even segments of the small intestine and transverse colon [2]. Trichobezoars are typically seen in women with an average age of 20 years and are often associated with psychiatric disorders [3-5]. The mass can be asymptomatic due to the high capacity of the stomach until it becomes larger, causing symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss and nutrient malabsorption, and even intestinal obstruction [6]. The purpose of this manuscript is to describe the clinical characteristics and the treatment of a case of Rapunzel Syndrome complicated by intestinal obstruction, a rare entity in clinical practice, in an adolescent patient with depression and anxiety disorder.

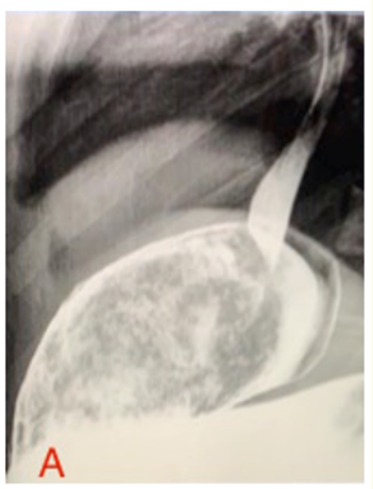

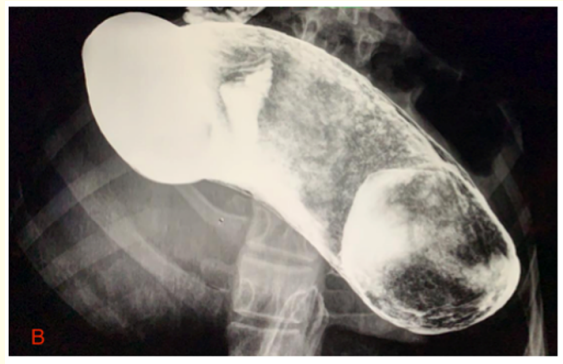

This is a 16-year-old female adolescent with a history of depression, anxiety disorder, ADHD, probable trichotillomania, 25OH vitamin D deficiency, iron deficiency anemia; in current treatment with Methylphenidate, Quetiapine, Escitalopram (make sure to use only generic drug names). She received treatment with Vitamin D and ferrous sulfate in adequate doses; in control with child psychiatry from the age of 12. At a developmental and behavioral pediatric consultation, the mother reported that for 3 months she had the following symptoms: preprandial nausea, feeling of regurgitation, heartburn, intermittent abdominal pain in epigastrium, doubtful dysphagia. Given the presence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux without obtaining precise information when questioning on a real difficulty in consuming solids, an upper gastrointestinal series with barium was requested. She was also evaluated by a pediatric gastroenterologist for the symptoms already described later associated with vomiting of food content and constant abdominal pain in the epigastrium with an intensity of 5/10. On physical examination the patient was hemodynamically stable, without signs of dehydration; head with generalized loss of hair density, without areas of inflammation, with short hairs of different sizes; neck without adenomegaly, thyroid not palpable; healthy mouth; cardiopulmonary, lung murmur present (what’s a lung murmur?) no added noise; heart sounds present, rhythmic and regular without murmurs; Abdominal level: decreased air-fluid sounds, painful on deep palpation and a mass was felt in the epigastrium extending to the left upper quadrant, adhered to the deep plane; Rest without alterations. Laboratories: Leukocytes 9,700 x 103/ul; Hematocrit 37.1%; Hemoglobin 11.7 g/dl; Mean Corpuscular Volume: 86.5 fl; Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin: 27.3 pg; Platelets 289,000; Patient Prothrombin Time 13.5 seconds; Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time 29.5 seconds. Glycemia 86 mg/dl; Urea nitrogen 7 mg/ dl; Urea 15 mg/dl; Creatininemia 0.7 mg/dl; Sodium 137.0 mEq/l; Potassium 4.2 mEq/l; Chlorine 100.5 mEq/l; Phosphorus 4.2 mg/ dl; Aspartate aminotransferase 23 ul; Alanine aminotransferase 16 ul; Glutamyl Transpeptidase Range 11.0 ul; Total protein 6.9 g/ dl; Albumin 4.7 g/dl; Globulins 2.1; Free thyroxine: 1.0 ng/dl; Thyrotropin: 2.48 mIU/mL (I suggest to make a table for the laboratory data). On imaging, upper gastrointestinal series with barium showed enlarged stomach with a mass that occupies its lumen, presenting a lumpy “honeycomb” appearance, all compatible with bezoar (Figure 1); Mild spontaneous gastroesophageal reflux is also described in decubitus. EDA revealed a mass of hair occupying the entire stomach and extending to the pylorus and duodenal bulb, the latter was not fully explored, since the foreign body prevented the passage of the endoscope. It was not possible to visualize the mucosa in its entirety, some segments showed inflammatory signs. The findings were consistent with gastroduodenal trichobezoar (Rapunzel syndrome) (Figure 2).

Figure 1A: Passing of contrast to the gastric chamber.

Figure 1B: Gastric chamber with dense content with areas of suggestive contrast impregnation with bezoar. It is evident 'surface in panel of bees.'

Figure 1C: Distended duodenal bulb with contrast and presence of air-fluid level suggestive of bezoar inside. It is evident 'surface in panel of bees'."

Figure 1: Upper gastrointestinal series with barium.

Figure 2A: Trichobezoar ascent through the lower esophageal sphincter.

Figure 2B: Trichobezoar.

Figure 2C: Trichobezoar passage through pylorus is evidenced.

Figure 2: Upper digestive endoscopy.

On te-evaluation, the patient confirmed a history of trichophagia for approximately 5 years (a report unknown to the parents and medical team). The patient underwent a median supraumbilical laparotomy observing great dilation of the stomach occupied by a mass of soft consistency. A longitudinal gastric incision of 8 cm was made, a trichobezoar is verified in the entire gastric cavity and pylorus to the duodenum and it is extracted manually, measuring 28.5 by 10 cm (Figure 3). The patient was discharged without post operative complications with subsequent controls with Pediatrics and Child Psychiatry.

Figure 3: Trichobezoar after extraction.

About 1 in 2,000 children worldwide suffer from trichotillomania and 30% of them will also suffer from trichophagia [7]. 1% of those with trichophagia will develop a trichobezoar [8]. Most trichobezoar patients suffer from psychiatric disorders. In a study of a total of 62 children with trichotillomania (8 to 17 years of age) Panza K., et al. describes that 30% had depression, 29% anxiety disorder and 16% ADHD; the average age of onset was 9.3 ± 2.6 years. Furthermore, 73% of the location of the plucked hair is from the scalp [9]. These findings described are similar to our patient who reports that she has practiced trichotillomania and trichophagia since the age 11 years old. She also had a history of ADHD from the school stage, and a diagnosis of depression and anxiety since she was 12 years old. In this same study, 82% of patients were women and 88% of the sample was Caucasian [9].

The signs and/or symptoms of trichobezoar that are described in the literature are: mobile mass in the epigastrium (70%), nausea and vomiting (64%), hematemesis (61%), weight loss (38%) and diarrhea or constipation (32%). The presence of these symptoms will depend on the elasticity of the stomach, the size of the bezoar and the appearance or not of complications [2]. There may be gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia that could be related to the development of ulceration in the gastric mucosa [10]. Gorter R., et al. analyzed 108 cases of trichobezoar and found the most common complications to be gastric/intestinal obstruction (10.1%); intuspection (10.1%); pancreatitis (0.9%); cholangitis (0.9%); others (10.1%) [11]. This clinical case exemplifies a less frequent form of presentation, that is, a trichobezoar with extension to the duodenum associated with complications (recovered Ferropriva anemia, currently Normocytic - Normochromic, in addition to symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction).

With regard to imaging studies, abdominal ultrasound reveals highly echogenic areas, but it is often not diagnostic [6,7]. Upper gastrointestinal series with barium admired with an intragastric amorphous mass that is generally mobile allows it to be differentiated from a malignant tumor [12]. It is also observed how the barium is trapped in the interstitium of the bezoar, producing an image of a honeycomb surface [13]. Computed tomography is of value in patients who require surgical removal of bezoars from the small intestine, not only because it demonstrates the obstructed site; but also because allows the visualization of multiple bezoars [14]. The EDA confirms the material that makes up the bezoar, allowing the different types of bezoar to be differentiated [2,11,14] and their extension, which is why it constitutes the test of choice and gold standard in the diagnostic stage.

Treatment can be medical, conventional laparotomy, laparoscopy, and endoscopic methods. There is no evidence of consistent successes from the use of medical treatments such as intragastric installation of sodium bicarbonate and coca cola. The use of laparoscopy for the removal of small to moderate bezoars has been described. Laparoscopic complications include longer operation time, migration of bezoars to the ileum, and abdominal cavity contamination [15]. Small trichobezoars can be removed endoscopically; successful endoscopic removals have been reported [16] and these are based on the use of intragastric chemicals (sodium bicarbonate) to dissolve the material, mechanical fragmentation, and removal of bezoars with repeated endoscopy [15]. Gorter., et al. conducted a review of 108 patients with trichobezoar and showed that endoscopic extraction was successful in only 5% of patients, while 92.5% were treated by laparotomy, with a success rate of 99% [11]. The low success rate of endoscopic extraction may be due to the increased risk of pressure ulceration, esophagitis and esophageal perforation due to repeated insertion of the endoscope and migration of bezoars distally that can obstruct the intestine [15]. The surgical treatment is the choice when the bezoar is large and compact, with special consideration in Rapunzel syndrome, in which multiple enterotomies may be necessary for its complete removal, and when there are complications such as perforation, obstruction or hemorrhage [17]. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed in our patient, due to the symptoms of acute abdomen (intestinal obstruction), size (large) and location (gastroduodenal). It is important to consider that although the consequence of the underlying disease has been eliminated, it can still recur if adequate psychological and psychiatric treatment is not maintained [5].

Rapunzel syndrome is a rare disease, important to consider in patients with a history of trichophagia and/or trichotillomania. It occurs mostly in young women. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the diagnostic method of choice. Laparotomy currently has better evidence as a technique for its resolution. It is necessary to monitor it with constant psychotherapy to avoid its recurrence.

Without any conflict of interest.

Copyright: © 2021 Daniel López H and Jessica Franco F. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.