Khouloud Abdulrhman Al-Sofyani1*, Mohammed Shahab Uddin2, Huda Saeed Alghamdi3 and Dalia El-Hossary4,5

1Department of Pediatric, Pediatric Intensive Critical Care Unit, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2Department of Pediatric, Pediatric Intensive Critical Care Unit, National Guard Health Affairs, Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

3Consultant Medical Microbiology, Clinical and Molecular Microbiological Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine and Medical Microbiology, King Abdulaziz Hospital, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

4Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

5Clinical and Molecular Microbiological Laboratory, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding Author: Khouloud Abdulrhman Al-Sofyani, Department of Pediatric, Pediatric Intensive Critical Care Unit, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Received: September 25, 2020; Published: October 28, 2020

Citation: Khouloud Abdulrhman Al-Sofyani., et al. “Comparative Analysis of Candida albicans Versus Candida Non-albicans Infection among Pediatric Patients at King Abdulaziz University Hospital”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 3.11 (2020):37-47.

Background: Candidemia is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality among critically ill pediatric patients. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of Candida infection, different strains, associated risk factors, and outcomes in critically ill patients with candidemia.

Method: Critically ill pediatric patients with invasive candidiasis were included in this retrospective study. Patients were 14 years or younger, admitted to King Abdulaziz University Hospital from March 2018 to February 2020.

Results: Out of 61 pediatric patients cases with candidemia, 23 (37.7%) patients were diagnosed with C. albicans and 38 (62.3%) with non-albicans. Species present in non-albicans Candida group included Candida parapsilosis 15 (24.6%), Candida topicalis 12 (19.7%) and Candida glabrata 4 (6.6%). Majority Candida strains were sensitive to antifungals. The main admitting diagnosis was sepsis 21 (34.4%) and the main isolation site of Candida species was blood. The main risk factors and predictors of candidemia were age younger than 5 months, presence of a central venous catheter, urinary catheter, using TPN, and blood products transfusion. Finally, the number of mortalities and length of ICU stay was higher among C. albicans patients, whereas the duration of hospitalization, broad-spectrum antimicrobial and antifungal treatment, were higher among C. non-albicans infected patients.

Conclusion: Although C. albicans infection cases are still dominant, however, the number of cases due to C. non-albicans infection is high. The study also highlighted some of the indicators that may help in early prophylactic intervention, which in turn can help improve the poor clinical prognostic outcome in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: Candidemia; Candida albicans; Candida non-albicans; Risk Factors; Outcome

PICU: Pediatric Critical Care Unit; TPN: Total Parenteral Nutrition; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; SBF: Sterile Body Fluids.

During the last few decades, incidences of fungal infections have become a major health problem in hospitals, where the episodes of sepsis caused by fungi have been increasing since the early 1990s [1-3]. Fungi are ubiquitous organisms that rarely cause disease in an otherwise healthy immunocompetent hosts. Only a few (~300) fungal species, from the millions of different fungal species, are known to cause disease [4,5]. Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) occur as a result of interaction between the organism’s pathogenic ability (colonization stage, propagation, adaptation, and/or dissemination) and the host immune defense and its response [4,6]. There are several reasons and risk factors that have led to a significant increase in the invasive fungal infection rate in the pediatric intensive care units over the past several decades. Several reasons for increased infections are underlying malignancy, greater use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, ICU stay for more than 72 hours, immunosuppressive therapy, presence of invasive devices such as central venous catheters (CVC), parenteral nutrition, and multiple uses of invasive procedures [7-13].

Among children, candidemia is the third most common cause of bloodstream infections in a hospital setting [7], and it also responsible for the second-highest case fatality rate in children with bloodstream infections [14].

Even with the advancement in the diagnostic procedures, development of new antifungal agents and application of newer strategies to prevent candidemia [1,6], the hematogenous candidiasis is difficult to diagnose, which ultimately results in extended hospitalization and a mortality rate of around 50%, along with high financial burden to health care systems [11,15-20]. The incidences of candidemia may significantly vary from one area to another. While the number of Candida non-albicans species are growing and show resistance to some antifungal agents, C. albicans is still the primary pathogen associated with candidemia [10,21-27]. In the last few years, several studies have confirmed the increasing cases of fluconazole and echinocandin resistant Candida spp. in the US and European countries [27-29]. Fluconazole resistance was reported among C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis strains in different regions [24,29-31].

The signs of Candida infection can range from a non-life threatening mucocutaneous disease to an aggressive disease that can affect any organ [32]. In children, the spread candidiasis is mostly observed in the lungs, kidney, liver, and brain, and the infection can be recurrent. The incidences of aggressive candidiasis are higher in children-mainly in the neonates-than in the adults [33]. Consequently, in the patients with amassing risk factors for candidemia, in whom the possibility for candidemia is high, clinicians order empirical treatment long before laboratory results on species identification and antibiograms are obtained as the clinicians assume that the infection is present [34,35].

Although there are many studies conducted on the prevalence of candidemia, there is limited data available in the Middle East regarding the distribution of Candida albicans and Candida non-albicans infections in the children. Therefore, we conducted this retrospective study to gain insights into the prevalence of candidiasis and its distribution in children in Saudi Arabia. The demographic data of the patients, isolation, and characterization of different Candida species was done, and their susceptibility to different antifungal agents was also tested. Potential risk factors associated with candidiasis were also identified. Further, we also analyzed the clinical outcome among infected patients.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University (Reference Number: 328-14).

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional study conducted from March 2018 to February 2020 in the Pediatric Critical Care Unit (PICU) at King Abdul-Aziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

In this study, we recruited pediatric patients younger than or equal to 14 years who developed invasive candidiasis during their stay in the PICU. Invasive candidiasis was diagnosed upon the isolation of Candida spp. from blood or sterile body fluids such as peritoneal fluid, pleural fluid, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and synovial fluid of each patient presenting clinical features of Candida infection. The first episode of the Candida infection was analyzed for those patients who suffered multiple episodes of candidemia during their hospital stay. We excluded those patients from the study in whom Candida was isolated from the tissues. Detection and species identification of the Candida isolates were performed according to KAUH laboratory standard protocols.

A data collection form was designed to gather patient information such as age, gender, nationality, reasons for PICU admission (medical, surgical, and trauma), and the isolation site. Predisposing risk factors included treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics (for ≥ 7 days), central venous catheter (for > 3 days), urinary catheter (for > 1 day), mechanical ventilation (for > 2 days), multiorgan failure due to sepsis, length of ICU stay, steroid therapy, chemotherapy, blood products transfusion, presence of peritoneal tube for dialysis and or chest tube, using total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Outcome after diagnosis included length of hospital stay, survived or diseased, ventilation duration, and duration of antifungal treatment.

To perform the blood cultures, an automated blood culture system (BacT/Alert, Organon, Teknika, USA) was employed. Inoculation of the blood samples (5 ml) was done in a single pediatric bottle. Subsequently, the culture bottles were loaded into BacT/ Alert blood culture and were kept until growth was detected or at the end of 5 days incubation time, if growth was not detected. All bottles that turned out to be positive were further subjected to Gram staining. Culture bottles that were positive for the yeast cells were subcultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) (Saudi prepared media Laboratories, Riyadh, KSA). Yeast cells were then identified with the help of VITEK MS on the same day, if sufficient growth was observed on the SDA. The identification (ID) and antifungal-susceptibility testing of the Candida species was performed by using VITEK®2 system (bioMerieux, Inc., France) [36].

Data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software ver. 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All collected variables were analyzed using descriptive and analytical statistics. Categorical variables were described and reported as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were described and reported as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between C. albicans and C. non-albicans groups were performed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and by using independent t-test or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

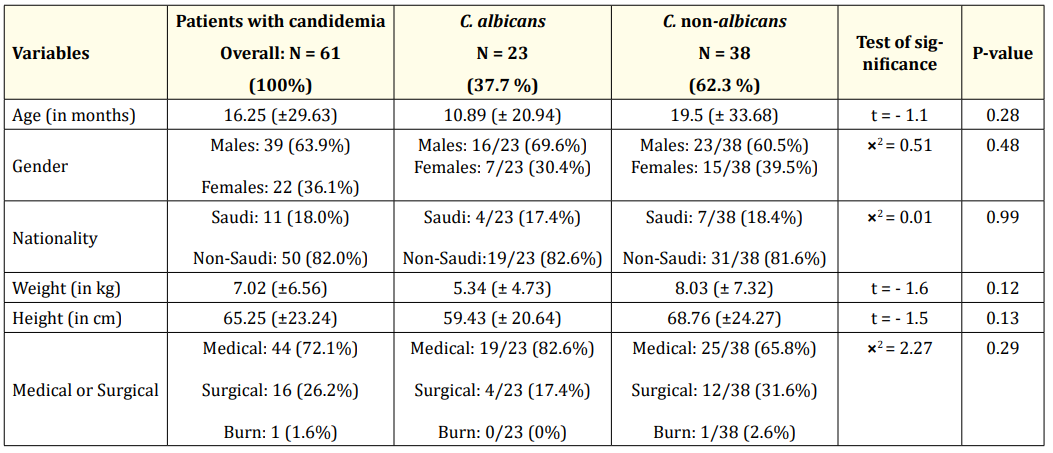

During this study period, 61 cases with candidemia were identified. Out of the 61 pediatric patients, 23 (37.7%) were diagnosed with C. albicans, whereas 38 (62.3%) patients were infected with non-albicans Candida spp. (Table 1). Among the patients infected with Candida, the number of male patients were 39 (63.9%) and 22 (36.1%) were female; 16/23 (69.6%) males had C. albicans vs 23/38 (60.5%) had C. non-albicans, and 7/23 (30.4%) females had C. albicans vs 15/38 (39.5%) had C. non-albicans. Further, the patients infected with C. albicans were relatively younger (10.89 ± 20.94 months) than the patients infected with C. non-albicans (19.5 ± 33.68 months) The majority of the cases were found in the non-Saudi patients (~82%), in both the groups. Finally, we found that most of the cases of candidemia (44; 72.1%) were admitted for medical reasons, where 19 (82.6%) had C. albicans and 25 (65.8%) had C. non-albicans. There were no significant differences between the two groups (C. albicans and C. non-albicans) regarding all demographic data (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the patients with Candida albicans and Candida non-albicans infection. Data are presented as mean ± SD or N (%).

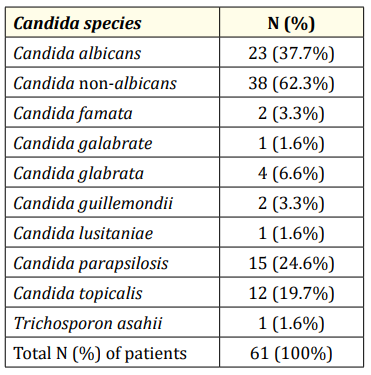

Among all the patients with candidemia, C. albicans was isolated from 23 (37.7%) patients, while non-albicans Candida spp. were isolated from 38 (62.3%) of the patients. Among the non-albicans Candida group, the majority of the fungal species isolated were Candida parapsilosis 15 (24.6%), Candida tropicalis 12 (19.7%), and Candida glabrata 4 (6.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2: Distribution of the various Candida species isolated from the patients.

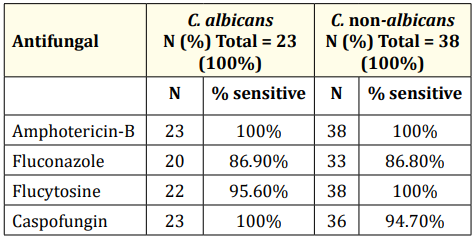

The results in table 3 show the susceptibility profile of the isolated Candida strains tested against different types of antifungals. The antifungals agents tested were amphotericin-B, fluconazole, flucytosine, and caspofungin. We observed that all 23 (100%) isolates of C. albicans were sensitive against amphotericin-B and caspofungin, while 3 isolates were found to be resistant to fluconazole and 1 isolate was resistant to flucytosine (Table 3). Among C. non-albicans isolates, all 38 (100%) strains were sensitive to amphotericin-B and flucytosine, while 5 isolates were resistant to fluconazole and 2 isolates were resistant to caspofungin (Table 3).

Table 3: Susceptibility profile of different Candida species towards various antifungal agents.

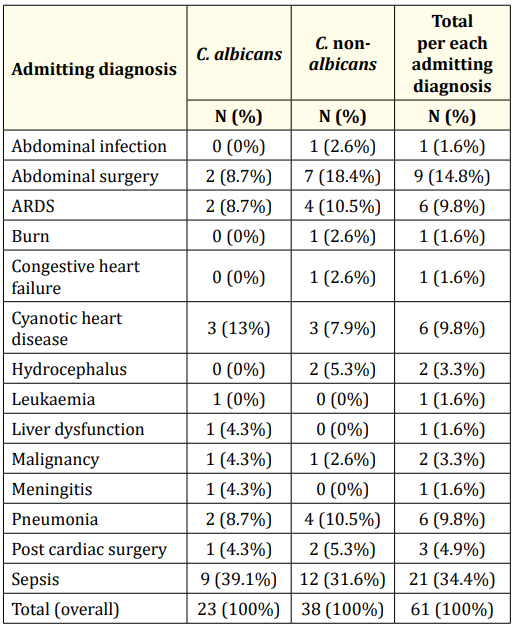

Next, we analyzed the admitting diagnosis for the patients with candidemia. Sepsis (21 patients; 34.4%) was observed to be the main admitting diagnosis, followed by abdominal surgery among 9 (14.8%) patients, and ARDS (Acute respiratory distress syndrome), cyanotic heart disease and pneumonia in 6 (9.8%) patients each (Table 4).

Table 4: Comparison between the patients with Candida albicans versus patients with Candida non-albicans regarding the patient diagnosis while admitting. ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

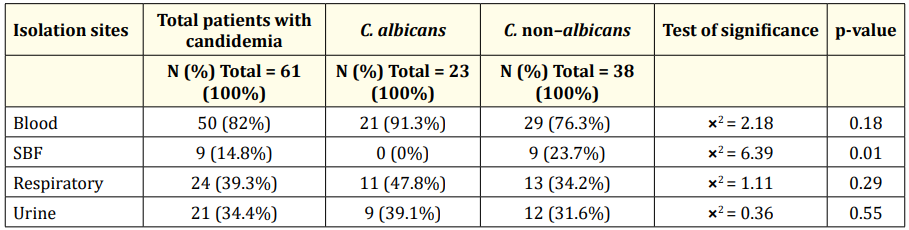

Regarding isolation site, overall, maximum number of Candia spp. were isolated from blood (50; 82.0%), followed by respiratory site (24; 39.3%), and urine (21; 34.4%) (Table 5). The least number of Candida spp. were isolated from the sterile body fluids (SBF) (9; 14.8%). Among the two groups C. albicans and C. nonalbicans, relatively, C. albicans were isolated from more number of patients as compared to the C. non-albicans from blood (21/23 [91.3%] vs 29/38 [76.3%]), respiratory site (11/23 [47.8%] vs 13/38 [34.2%]) and urine (9/23 [39.1%] vs 12/38 [31.6%]). Significant difference between the two groups was observed regarding the isolation site sterile body fluids (SBF), where C. albicans was not detected in any case while C. non-albicans was isolated from 9 patients (23.7%) (p = 0.01) (Table 5).

Table 5: Comparison between patients with Candida albicans versus the patients with Candida non-albicans regarding isolation sites. Data are presented as mean ± SD or N (%). SBF: Sterile Body Fluids.

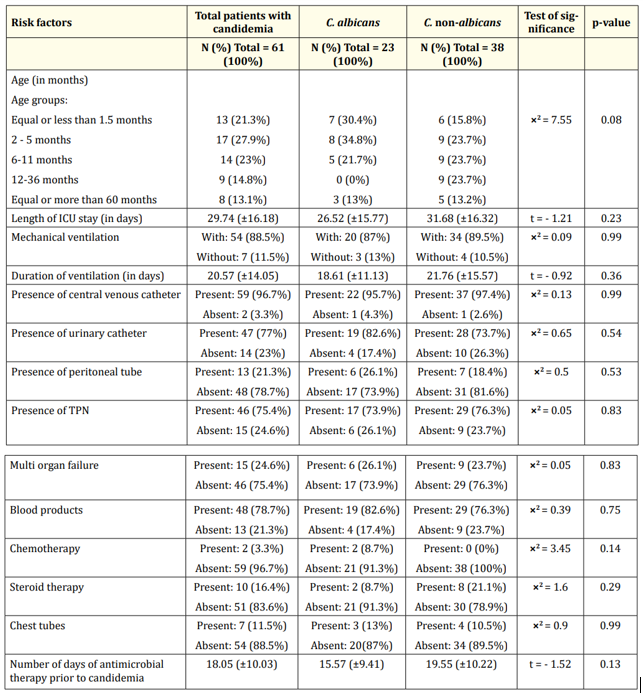

We next analyzed the risk factors associated with the patients suffering from candidiasis. We observed that the difference between the two groups, regarding the risk factors, was not statistically significant. However, the proportion of C. albicans patients was higher than C. non-albicans ones among the cases with the following risk factors: younger than 5 months (15/23 [65.2%] vs 15/38 [39.5%]), presence of urinary catheter (19/23 [82.6%] vs 28/38 [73.7%]), peritoneal tube (6/23 [26.1%] vs 7/38 [18.4%]), multi organ failure (6/23 [26.1%] vs 9/38 [23.7%]), blood product transfusions (19/23 [82.6%] vs 29/38 [76.3%]), chemotherapy (2/23 [8.7%] vs 0/38 [0.0%]), and chest tubes (3/23 [13.0%] vs 4/38 [10.5%]) (Table 6).

Table 6: Comparison between patients with Candida albicans versus patients with Candida non-albicans regarding risk factors. Data are presented as mean ± SD or N (%). TPN: Total Parenteral Nutrition.

On the other hand, the rate of C. non-albicans was higher than C. albicans among the cases with the following risk factors: Length of ICU stay (31.68 vs 26.53 days), central venous catheter (37/38 [97.4%] vs 22/23 [95.7%]), total parenteral nutrition (TPN) (29/38 [76.3%] vs 17/23 [73.9%]), steroid therapy (8/38 [21.1%] vs 2/23 [8.7%]), days of broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy prior to candidemia (19.55 vs 15.57 days), mechanical ventilation (34/38 [89.5%] vs 20/23 [87.0%]) and duration of ventilation (21.76 vs 18.61 days) (Table 6).

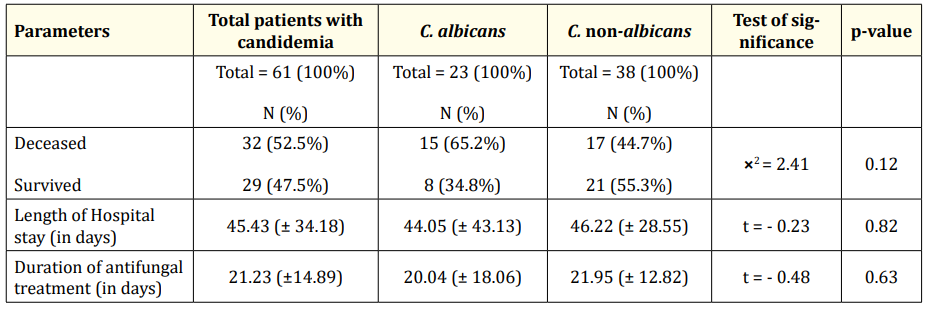

Finally, we studied the outcomes of the patients suffering from candidemia. We found that the mortality rate was higher among the C. albicans infected patients than the ones infected with C. nonalbicans (15/23 [65.2%] vs 17/38 [44.7%]) (Table 7). However, the length of hospitalization and the duration of the treatment with antifungals were relatively higher among C. non-albicans than the C. albicans infected group, 46.22 vs 44.05 days and 21.95 vs 20.04 days, respectively; the differences were not significant (Table 7).

Table 7: Comparison between the patients with Candida albicans versus patients with Candida non-albicans regarding outcomes. Data are presented as mean ± SD or N (%).

Aggressive fungal infections such as invasive candidiasis (IC) and invasive aspergillosis (IA) have resulted in an expanding public health problem globally, including the Arab world [37-39]. These infections burden the healthcare system due to associated high morbidity, mortality, and the cost of care [37,40]. Several factors related to the patients and environment influence the epidemiology of invasive fungal infections; these factors depend on the geographic region [37-42], and variations are found among continents and countries, or within the same area [37,43].

Our study included 61 pediatric patients with invasive candidiasis from a tertiary medical center in Saudi Arabia. In this study, we attempted to understand the outcomes, mortality rate, and risk factors among the patients of this study group. Among all the patients with candidemia, around two-thirds of the cases had C. non- albicans infection, while the remaining one-third had C. albicans infection. These results concur with the findings of similar study performed in Saudi Arabia, where C. non- albicans cases were more than half (54.3%) of all the cases detected, and the rest of the cases (45.7%) were infected with C. albicans. Also, in a large multi-center, multi-national study of pediatric candidiasis, which included 30 participating sites (20 in the US and 10 international), of the 449 Candida isolates, C. albicans (40%) was the most common species, but collectively, the non-albicans Candida species were dominant (60%) [44]. Similarly, in a study conducted in Brazil, it was found that the C. non-albicans species accounted for 65.7% of the total cases, while the C. albicans species accounted for the rest 34.3% of the cases [9]. Likewise, the most extensive and contemporary retrospective review from a single pediatric center (patients aged 6 months to 18 years old) found that C. albicans was the most commonly isolated (44.2%) species during invasive candidemia, followed by C. parapsilosis (23.9%) [45]. Further, in a study conducted in Italy, the rate of C. albicans infection was found to be 49%, and the prevalence of C. non- albicans was 51%, which included species like C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata and C. tropicalis [46].

These results show that despite the fact that C. albicans is still the main pathogen associated with candidemia, there is an increase in the rate of infection by C. non-albicans, which in turn has become a serious health challenge. This observation has been reported by several other studies and identified different reasons for this phenomenon. The first one is due to the use of fluconazole as prophylaxis [47-49]. Another reason, at least in part, is reflective of more accurate identification of yeast isolates at the species level [6]. However, the reasons for this growth in the rate of C. non-albicans are not yet totally understood [46].

In the current study, the primary admitting diagnosis was sepsis, which was observed among a third of the total cases (21; 34.4%). In a study performed in the USA, fungi were the second most common pathogen to be identified in the cases of sepsis [50,51]. While, in another study, the main underlying condition was found to be malignancies [9].

Although the occurrence of invasive candidiasis is similar in both pediatrics and adults, there were significant differences in the host factors, pharmacokinetics, and outcomes in children than adults [20, 52-56]. Candidiasis excessively affects critically ill children. In a study conducted in the USA, almost 50% of the candidemia cases in children were found to occur in the patients admitted in PICU setting [20]. In addition, other studies also reported higher mortality rate among the children admitted in the PICU [56,57]. The results of the current study are consistent with the previous study, where extended stay in PICU caused Candida infections (≥ 45 days).

In a single-center study, Zaoutis., et al. reported the presence of a central venous catheter, recent exposure to parenteral nutrition, recent exposure to certain antimicrobial agents vancomycin, antianaerobic agents and underlying malignancy as the risk factors which are also the clinical predictors of candidemia among pediatric ICU patients (OR-46%; 95% CI- 19% - 75%) [58]. In another study, the most common risk factors identified were the number of antibiotics received prior to candidemia development, previous hemodialysis, recent extensive gastro-abdominal surgery, isolation of Candida spp. from sites other than blood, prior use of a Hickman catheter, and the length of ICU stay [46]. Further, in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia, the main predictors of candidemia among the patients in PICU were prematurity, low birth weight, presence of a central venous catheter, malignancy, immunotherapy, and the required use of mechanical ventilators [14]. In the current study, we observed that the main risk factors and predictors of candidemia were age younger than 1 year, presence of a central venous catheter, presence of a urinary catheter, presence of TPN, blood products, required use of mechanical ventilators, and prior treatment with broad-spectrum antimicrobials. These differences in the results could be due to several factors, such as different geographic areas, sample size, and the nature of the studies.

The current study revealed good in vitro sensitivity rates of the Candida species to the available antifungal medication in the current hospital. In the 61 Candida isolates tested for sensitivity, majority of the C. albicans and C. non-albicans strains showed sensitivity to the following antifungal agents: amphotericin-B, fluconazole, flucytosine, and caspofungin. This susceptibility pattern is similar to that described in a review by Omrani., et al. [59], and Almoosa., et al. [14], where they reported good susceptibility patterns to all antifungal medications.

It is well known that Candida blood stream infections (BSIs) severely compromise the survival of ICU patients. In the EPIC II survey, it was observed that the patients with candidemia have the highest (42.6%) crude ICU mortality as compared to the patients suffering from Gram-positive (25.3%) and Gram-negative (29.1%) bacterial infections [46]. The overall mortality observed in our study is in agreement with the previous local, regional, and international studies. In their study, Al Thaqafi., et al. reported that the patient mortality rate was 50% [33] while, Pfaller., et al. observed that there was high crude mortality of 46-75% [24]. Also, in a hospital study conducted in Brazil, the crude mortality among the candidemia patients was found to be 72% [9]. However, a low mortality rate of 36.4% was also reported in a study, which was a deviation from other studies [14]. Although, in the studies conducted in Italy and Greece, increased mortality was reported in patients with Candida albicans blood stream infections (BSIs) [46,60], however, other studies did not support this correlation [61, 62]. In the current study, the mortality rate was higher in patients infected with C. albicans than C. non-albicans spp. (65.2% vs. 44.7%, respectively), which is in agreement with the findings of most of the earlier studies.

Although Candida albicans is the most commonly isolated Candida species, infections due to non-albicans species are increasing. In general, invasive candidiasis has a poor clinical prognostic outcome in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This study has shown that a lower proportion of deaths occur within the non-albicans infected group of patients. The study’s main limitation is its retrospective nature and the dependence on the data obtained from one hospital only. Nonetheless, our findings also highlight the common indicators that may guide early prophylactic intervention. There is a need for more retrospective and detailed multi-center studies to enable the medical community better define the risks and optimal strategies for the early diagnosis of candidemia.

The authors declare no competing financial interest. Furthermore, the work was not supported or funded by any drug company.

Copyright: © 2020 Khouloud Abdulrhman Al-Sofyani., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.