Nira Tamang1,2*, Saroj Rai3, Ping Ni2 and Jing Mao2

1Department of Nursing, Norvic International Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal

2School of Nursing, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

3Department of Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, National Trauma Center, National Academy of Medical Sciences, Kathmandu, Nepal

*Corresponding Author: Nira Tamang, Department of Nursing, Norvic International Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Received: June 27, 2020; Published: July 30, 2020

Citation: Nira Tamang., et al. “Perceived Level of Stress, Stressors and Coping Strategies among Undergraduate Health Professional Students during their Clinical Education: A Comparative Study”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 3.8 (2020):62-73.

Purpose: This study aimed to determine and compare the stress level, stressors and coping strategies and to investigate the relationship between stress, coping strategy and demographic characteristics among undergraduate health professional students.

Methods: In this cross-sectional, non-experimental and comparative study, a convenience sampling technique used to collect data from 280 students. We used a self-reported questionnaire including demographic characteristics of participants, Perceived Stress Scale, and Coping Behavior Inventory.

Results: Health professional students reported overall moderate level of stress while, nursing students showed mild stress whereas dental and clinical medicine students showed moderate stress. However, students were highly stressed by patient’s care, assignment and workload, lack of professional knowledge and skills, and environment, and minimally stressed by peers and daily life and teachers and other staffs. Stay-optimistic was mostly used coping strategy by nursing students and transference by dental and clinical medicine students whereas avoidance was the least used by all. Significant correlation of stress was found with coping strategy and previous health training.

Conclusion and Clinical Implications: Students face varieties of stressors during their clinical education. Therefore, students should be encouraged and motivated to adopt effective coping. Additionally, health training found positive role in reducing student’s stress so that medical courses are very necessary to the students before entering medical school.

Keywords: Stress; Stressor; Coping Strategy; Clinical Education; Health Professional Students

Stress is a universal phenomenon and is inevitable [1,2]. It is known as a reaction towards some events such as an environmental condition that alters the physical or mental equilibrium [3]. Education is itself demanding, challenging and stressful. Psychological problems like stress, anxiety, depression have been reported all over the world among university students [4]. Stress is frequently associated with negative events, but it can also result from positive life incidence such as getting admission in the professional program and starting of career [5,6]. Similarly, stress can lead to varieties of negative events however the minimal level of stress is regarded as motivating factors to enhance the student’s creativity, learning ability and successful academic achievement [5,7-9].

University students are increasingly facing stress, and health professional students are more prone to stress than other university peers [7,10]. A professional career demands a great deal of hard work and persistence and brings new challenges for students in everyday life [11]. Most of the students don’t understand these demands and suffer from stress and anxiety [11]. Due to a negative impact on student’s physical and mental health, the stress has received tremendous attention [10]. Thus, the stress-related studies have largely been conducted among health professional students [4,12-14]. However, a very few have focused on comparative study [15-19]. These studies have reported variances in the level of perceived stress, not only among the groups but also within the groups. These differences are because of differences in measurement tools, places, religion and cultural beliefs, sample size and sampling technique, lack of comparison and differences in authors. Some studies reported a higher level of stress in nursing students [20], some in dental students [17] and some in clinical medicine students [19,21,22].

A stressor is an event or any stimulus that cause an individual to experience stress [23]. Stressors can be divided into various types such as; academic-related, clinical training related, psychosocialrelated and health-related factors [24]. Academic-related stressors include work-load, frequent examination, assignments, fear of failure and not getting expected marks, vast syllabus, academic competition with peers [15,25]. Similarly, clinical training related stressors include clinical procedures, performance pressure, completion of clinical requirement, difficulty in managing difficult cases, poor learning environment and lack of patient’s co-operation [15]. Moreover, psycho-social factors include worrying about future and high parental expectations, lack of recreation [24]. Health-related factors include lack of healthy diets, sleep problems, illness [24].

It is a well-known fact that the coping abilities are different in every individual [11]. Regular contact with the stressors leads to handle or control the situation [2]. Students use varieties of coping strategies and are mainly divided into problem-focussed, and emotional-focused [25]. Problem-focused coping is positive and effective coping which includes identification of the problem, planning, and solving of the problem [25]. It can eliminate the existing problem and reduces stress [26]. Emotional-focused coping focuses on the emotion rather than a problem, where individual use different ways of coping [27]. Emotional-focused coping includes listening to music, doing exercises and talking with family, etc. [15]. It reduces stress only for short period because it does not eliminate the actual problem [27]. These coping are still positive but not effective. Sometimes, students use negative and ineffective coping strategies such as smoking drinking, taking of medicine and even suicidal thoughts [5,9,10,28]. Similarly, some succeed to cope-up and results in positive consequences; whereas some fails and likely suffer from negative consequences [29]. It is proven that strees and coping are significantly associated [30]. Meanwhile, Students who adopt problem-focused coping suffer lower stress, whereas students who adopt emotional-focused coping experience higher stress [26,29]. However, the most commonly used coping strategies by these students are positive such as problem-solving, optimism, sleeping, meditation, instrumental support, and social support, etc.

[1,11,13,15,25,27,31-33].

This study aimed to determine and compare the level of perceived stress, to identify the different stressors, to explore the coping strategies, and to investigate the relationship between stress, coping and demographic characteristics among undergraduate health professional students.

We conducted a cross-sectional, non-experimental, and comparative study to assess the perceived level of stress, stressors, and coping strategies adopted by undergraduate health professional students.

Research instrument included Demographic characteristics of participants, Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and Coping Behavior Inventory (CBI) by She., et al.

It included age, gender, marital status, previous health-related training, religion, involvement of family member in the medical field, interest in studying medical field and continuation of work.

We used PSS and CBI scales according to Sheu., et al. [25,34]. PSS consisted of 5-point Likert scale having 29-items grouped into 6 factors. These factors included stress from taking care of patients (8-items), stress from teachers and other staffs (6-items), stress from assignment and workload (5-items), stress from peers and daily life (4-items), stress from lack of professional knowledge and skills (3-items), and stress from environment (3-items). Participants’ response was from 0 to 4. Higher scores represented a higher level of stress. A score of 0 to 1.33 was rated as mild stress, 1.34 to 2.66 as moderate stress and 2.67 to 4 as severe stress. Similarly, CBI also consisted of 5-point Likert scale having 19-items grouped into 4 factors. These factors included avoidance (6-items), problem-solving (6-items), stay-optimistic (4-items), and transference (3-items). Higher scores in one factor indicated the frequent use of coping behaviors.

We performed pre-test among first 30 health professional students including 10 students in each group and adopted good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.96 for PSS, and 0.74 for CBI). After good reliability of the instruments, questionnaires were distributed to 320 students but only 305 questionnaires received back. Of them, 25 returned questions were incomplete and unclear so excluded from the study. Finally, 280 clinical years students were included in this study.

Out of 280 students, 90 were nursing students, 90 were dental students, and remaining 100 were clinical medicine students. Nonprobability convenience sampling method was used for data collection. Non-clinical years or absent clinical years students.

Data collection was performed on January 2018. Both Chinese and English version questionnaires were circulated to the participants during clinical posting. It took about 15 to 20 minutes to complete the form. Informed consent was taken from each participant. Participants were not forced to fill up, and allowed to reject any time if they feel discomfort. The study was approved by the University Ethical Committee.

We used Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 for data analysis. One way ANOVA and Chi-square test were used to analyze continuous data and categorical data respectively. Pearson correlation was used to investigate the relationship between stress, coping strategy and demographic variables. The descriptive statistical analysis was completed for demographic variables. Graphs were prepared using Microsoft Excel for data representation. Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD, whereas categorical data were presented as number (n) or percentage (%).

Demographic characteristics of the participants are well illustrated in table 1.

Table 1: Demographic parameters of health professional students (mean ± SD, n, %). n: Sample size; SD: Standard Deviation; S: Single; M: Married; Y: Yes; N: No.

The statistically significant difference among three groups was observed (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). However, no significant difference was observed between dental and clinical medicine (P > 0.05). According to evaluation criteria, nursing students reported a mild level of stress with an average of 1.31 ± 0.57, whereas dental and clinical medicine students reported the moderate level of stress with an average of 1.65 ± 0.51 and 1.73 ± 0.50 respectively. However, undergraduate health professional students reported overall moderate level of stress with an average of 1.57 ± 0.55.

The highly reported stressors were patient’s care, assignment and workload, lack of professional knowledge and skills and environment whereas peers and daily life and teachers and other staffs were less reported stressors. Detail information of the stressors are well depicted in table 2. In addition, table 3 shows top five and least five reported stressors among 29 items of PSS by all the students.

Figure 1

The coping strategies used to overcome stress by nursing students was stay-optimistic (2.43 ± 0.64) followed by problem-solving (2.11 ± 0.85) and transference (2.09 ± 0.76).Whereas, dental and clinical medicine students used transference as the primary coping strategy (2.25 ± 0.62, and 2.10 ± 0.76, respectively) followed by stay-optimistic (2.24 ± 0.54, and 2.07 ± 0.60, respectively) and problem-solving (2.08 ± 0.57, and 1.95 ± 0.67, respectively). Avoidance was minimally used coping strategy by all the students. Additionally, table 4 shows the top five and least five coping behaviors among 19 items of CBI adopted by all the students.

Table 2: Commonly reported stressors among health professional students in descending order (mean ± SD). n: Sample Size; SD: Standard Deviation.

Table 3: Top five and least five stressors from 29 items of PSS reported by health professional students (mean ± SD). n: Sample Size; SD: Standard Deviation.

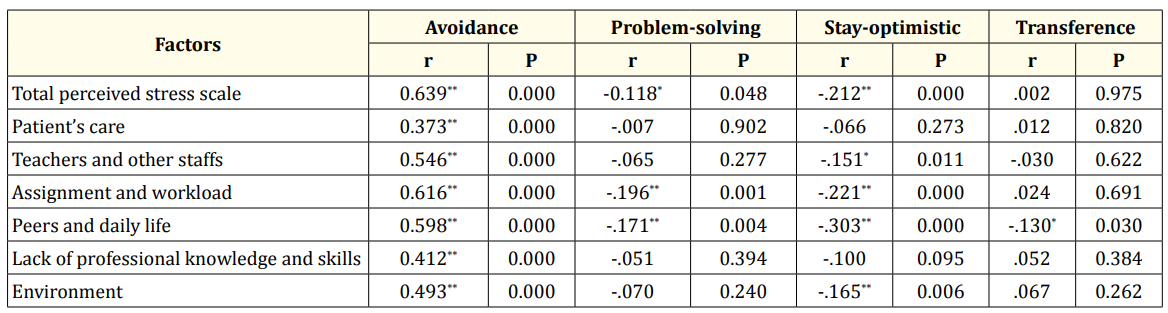

Details of correlations are illustrated in table 5. The overall stress was negatively correlated with stay-optimistic (r = -.212, P = .001) and problem-solving (r = -.118, P = .048) and positively correlated with avoidance (r = .639, P = .001), however no any association was found with transference (P > 0.05). It represented the lower level of stress among students who adopted problem solving and stay-optimistic, whereas higher stress who used avoidance. Moreover, we found statistically significant positive correlation between previous health-related training and stress level (r = .182, P = .002). It meant that students who received previous health-related trainings reported to have a lower level of stress.

In our study, nursing students reported the mild level of stress, whereas dental and clinical medicine students reported the moderate level of stress. The most commonly reported stressors by nursing students and clinical medicine students were assignment and workload, patient’s care and lack of professional knowledge and skills, whereas by dental students were assignment and workload, environment, and patient’s care. Similarly, the least reported stressors were peers and daily life by nursing and clinical medicine students and teachers and other staffs by dental students. Moreover, nursing students used stay-optimistic followed by problemsolving strategies to cope-up with the stress, whereas dental and clinical medicine students used transference followed by stay-optimistic. Avoidance was the least used coping behavior by all the students. Pearson correlation coefficient showed significant association between stress with coping and previous health related training.

Many studies have been performed to determine the level of perceived stress, type of stressors, and coping strategies among health professional students [15,16]. However, they all reported conflicting results [17,20,21]. It has been proven that the health care students are more prone to stress compared to other non-health related students during their study periods [10,28], especially when they are in their clinical years [7]. However, comparative studies among health professional students are still scarce [15-18,24]. Our result showed that the clinical medicine students reported a higher level of stress and the nursing students reported a lower level of stress. Racic., et al. [19] and Dutta., et al. [21] reported a similar result of clinical medicine students having a higher level of stress than dental and nursing students. In contrast, Zarifsanaiey., et al. [20] reported a higher level of stress in the nursing students compared to medical students. While, Murphy., et al. [35] and Birks., et al. [17] found dental students to be stressed more than students of other faculties.

Table 4: Top five and least five coping behavior adopted by health professional students (mean ± SD). n: Sample Size; SD: Standard Deviation.

Table 5: Correlation between stress, stressors and coping strategies. **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed); *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). R: Correlation coefficient; P: Level of significance.

Both academic and clinical education acknowledged as very stressful for health professional students, as they are highly stressed by academic as well as clinical factors [15,36]. Students encounter varieties of stressor during their clinical placement. In our study, the most commonly reported stressors by nursing and clinical medicine students were patient’s care, assignment and workload, and lack of professional knowledge and skills. Similarly, dental students reported patient’s care, environment, and assignment and workload as frequently noticed stressors. Stressors faced by health profssional students are consistent with previous studies [25,27,31]. Sheu., et al. [25], Chan., et al. [27], and Shaban., et al. [31] had conducted studies among undergraduate nursing students using the same tool. They found patient’s care, assignment and workload, lack of professional knowledge and skills and the environment to be the most commonly reported stressors. Moreover, supporting our results, commonly reported stressors by dental and clinical medicine students were academic workload [36], frequency of examination [15,37], fear of failure or not getting expected marks [6,38], academic competition with peers, difficulty in managing difficult cases, lack of cooperation of the patients [39], performance pressure 40 and poor learning environment [36,37,41].

In our study, the least reported stressor was peers and daily life by the nursing and clinical medicine students, whereas teachers and other staffs by the dental students, and was similar with the reports by Sheu., et al. [25] and Gomati., et al. [15]. However, Zhao., et al. [32] and AL Gamal., et al. [42] reported these as the second most common stressors, as their participants reported feel pressure from their teachers who evaluate the student’s performance by comparison (peers and daily life) and teachers do not give a fair evaluation of students (stress from teachers and other staffs). We know that comparison works somehow and sometimes but not always so a teacher should be aware of unnecessary comparison. Teachers cannot be right all the time; sometimes they also need to adopt some new behavior such as characteristics of a good teacher and should provide a fair evaluation. On the contrary, Labrague., et al. [12] reported patient’s care as the least reported stressor in Nigeria and Greece compared to Philippines nursing students. The reason could be less clinical exposure. Similarly, Zhao., et al. [32] and AL Gamal., et al. [42] found lack of professional knowledge and skills and environment as the least reported stressors. According to Zhao, all their participants had a former hospital posting for at least for three months [32]. Similarly, AL Gamal also included students who completed at least one clinical course [42]. Therefore, these students somehow mastered specific professional knowledge and skills and also became familiar with the clinical environment. In our study, we found these stressors to be highly reported because we included all the clinical year students even who had just started their clinical practice.

Undergraduate health professional students used varieties of coping strategies to handle the stressful situation [2,15,25]. Some students adopted positive coping strategies while others adopted negative [15,28]. Previous reports suggested that students who suffered higher stress used coping strategies such as avoidance and transference, whereas students who suffered lower stress used coping strategies, such as problem-solving and stay-optimistic [7,15,25,27,42]. The types of coping are also related to the place and the cultural beliefs. Gomathi., et al. [15] found praying or meditation in UAE. Ksiazek., et al. [23] reported listening to music and sleeping in Poland. Our study also supports the reports of the previous study that the nursing students used stay-optimistic as a primary coping strategy while the dental and clinical medicine students used transference. According to Chinese culture, Chinese students would keep calm even if they face difficulties [43] and adopt emotional oriented coping [27]. Similarly, clinical education is generally short course, so the students would suppose pointless to solve the problem instead they use transference, which is convenient and approachable [27]. On the other hand, avoidance was the least reported coping by all the students in our study. Similar results were reported by Zhao., et al. [32] and Shaban., et al. [31], whereas Sandover., et al. [33]and Gamal., et al. [42] reported commonly used coping strategy.

Correlational analysis of our study revealed that the students who adopted positive coping strategies such as stay-optimistic and problem-solving were suffered from lower stress. Supporting our results, Gamal., et al. [42] also reported significant positive correlation between stress and problem-solving which represented lower stress among those students who adopted problem-solving. In addition, there was a significant correlation between previous health-related training with stress level, which provided evidence that health training might be essential in reducing student’s stress level. Moreover, Labrague., et al. [44] also found significant association between only one academic year with stress level. Whereas, Gamal., et al. [42] found significant association between GPA with stress, age with problem-solving and stay-optimistic, and income with problem-solving.

Before hospital posting, students should be well prepared for their clinical education. Firstly, the students should get the prior orientation of clinical areas such as hospital situation, arrangements, ward facilities, rules, regulation and policy of the hospital. Prior orientation provides the students to be familiar with the clinical environment which reduces their stress level. Thus they will be able to deal with the patients confidently. Secondly, It is essential to finish theory and extra classes regarding the common and new problems, diseases, treatment protocol, medical terminologies before their clinical placement. Thirdly, students should have a thorough practice of common procedures on dummy under the direct teacher’s supervision. Prior practice and exposure helps them to know the nature of clinical work and builds up the confidence to make the correct decision and to provide need-based care. During simulation in the laboratory, close supervision of a teacher is essential to correct the error and wrongful practice.

During the academic session, the majority of the students become unaware of their identity and professional life. They often become anxious when they face reality or become direct contact with the patients in the hospital. Therefore, students must be well informed about their roles and responsibilities before entering into actual professional life. Instructors should frequently arrange drama classes and involve the students regarding their roles and responsibilities. This helps the student to know “who they are” and further helps them to accept reality and understand the changing pattern of professional life.

Time management and problem prioritization is another crucial factor, which needs to be learned by the students. If they have good knowledge about it, they can formulate their schedules for their daily tasks so that they can finish their work on stipulated time and even have extra-time for the preparation of their exams. That further helps to gain the confidence and decreases the worry regarding the exams.

Communication also plays a vital role in establishing and maintaining a healthy learning environment. Open communication between the teachers and students helps to share each other’s view and ideas. The teachers can ask students about their problems and help them to solve. Similarly, students also get time to know teacher’s view on their problems and even the teachers can share their own experience during their clinical posting. A good communication helps not only to share information but also to understands the each other’s opinion which eventually leads to a healthy learning environment fulfilling their expectations. Similarly, education programs like presentations, seminars, and workshops are necessary to enhance intercommunication techniques between teachers, students, and other hospital staffs. These programs help the student to be well prepared to handle the situation for a possible change in patient’s condition.

Not only the students but also the teachers need to change certain behaviors and adopt good characteristics of a teacher. Instructors should encourage and motivate students to use positive and effective coping such as problem-solving. Similarly, a regular review of the curriculum is necessary as the majority of the students are reporting academic related stress. Curriculum makers should take the feedback from the students and make necessary changes.

The strength of our study is a comparative study in 3 different groups using the same instrument. However, there are several limiting factors. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study. According to Lazarus and Folkman 2, stress is dynamic construct and can change over time due to adaptation, effective coping and changes in personal skills. So, the longitudinal study is recommended to observe changes. Secondly, being a quantitative study, we could not get the participation views about stress, stressors and ways of coping. A qualitative study with a mixed method could have performed to know the participant’s feeling. Thirdly, convenience sampling method in a relatively small size was used, randomization with larger cohorts could have provided different results with a higher level of evidence.

Our study concluded that health professional students reported overall moderate level of stress, whereas the nursing students reported a lower level of stress as compared to dental and clinical medicine students. However, they were mainly stressed by patient’s care, assignment and workload and less stressed by peers and daily life, and teachers and other staffs. Meanwhile, stay-optimistic and transference were the most frequently used coping strategies by all the students and avoidance was the least used. These adopted coping strategies were positive but not effective. Therefore, students should be encouraged and motivated to adopt effective coping strategy such as problem-solving. Correlation among variables showed previous health-related trainig to be responsible to reduce stress level.

None.

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Asamaporn Kaosala, Yam Sharma, Ying Yang, Xu Zhang and Yi Li for their tremendous support during the data collection. The authors would also like to thank all the participants.

Copyright: © 2020 Nira Tamang., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.