Gonen Ayala1* and Grinberg Keren2

1Senior Lecturer, Nursing Department, Faculty of Social and Community Sciences, Ruppin Academic Center, Emeq-Hefer, Israel

2Head of the Nursing Department, Faculty of Social and Community Sciences, Ruppin Academic Center, Emeq-Hefer, Israel

*Corresponding Author: Gonen Ayala, Senior Lecturer, Nursing Department, Faculty of Social and Community Sciences, Ruppin Academic Center, Emeq-Hefer, Israel.

Received: April 25, 2020; Published: July 25, 2020

Citation: Gonen Ayala and Grinberg Keren. “The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Burnout among Nursing Students”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 3.8 (2020):10-18.

Understanding the relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout among nursing students can provide insights on how to educate nursing students in effective conflict management that can occur both during clinical experience and in their future as nurses.

The Main Aim: To examine the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among nursing students.

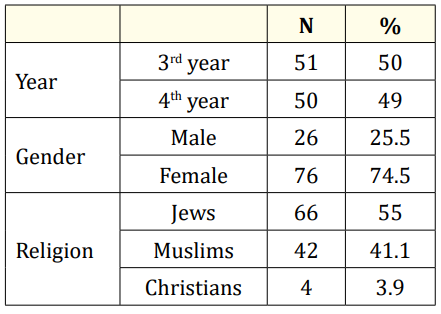

Methods: A quantitative research was carried out among third- and fourth-year nursing students aged 21 - 33 years old. A total of 102 questionnaires (85% response rate) were received.

Results: The higher the emotional intelligence level, the lower the burnout level (p = .001), and vice versa. Differences were found between male and female students: female students were less worn out than male students, and between Jewish and Arab students:

Jewish students were less worn out than Arab students.

Conclusion: There is a need to invest resources in the development and training of emotional intelligence in nursing education programs, in order to improve students’ emotional intelligence.

Keywords: Emotional Intelligence; Burnout; Nursing Students; Gender; Training

Emotional intelligence and the nursing profession: Emotional intelligence is a concept that fascinates academic scholars, the business world, and health care professionals. Only recently has the importance and effectiveness of emotional intelligence in people’s work been recognized [1]. Emotions affect thinking and are essential for people to make the right decisions, to best solve problems, to cope with change, and to succeed [2]. Emotional intelligence is actually a mixture of abilities to identify emotions, integrate emotional information into problem solving processes, perceive and cope with the complexity of emotions and the regulation of emotions in oneself and one’s environment [2].

Nursing is a stressful occupation. Exposure of students to clinical fields in the early stages of studies, and the reality of working as health professionals, can lead to increased levels of stress and anxiety. Therefore, nursing students need to develop the ability to control emotions and channel their moods in a beneficial way. There are other reasons for the potential relationship between emotional intelligence and nurses’ effective functioning. One reason is that emotions are essential in creating and maintaining a caring and empathic environment. Nurses’ ability to associate with patients, manage their emotions, and empathize with patients is critical to providing high quality care. Improving emotional intelligence skills may also help nurses cope with the emotional demands of working in a health environment that can be stressful, debilitating and may even lead to burnout [3].

In addition, the characteristics of emotional intelligence are associated with organizational variables such as job satisfaction and health, including low stress levels, subjective wellbeing, and various aspects of nurses’ team performance [4]. In a study of nursing students, Arieli [5] claimed that nursing students in clinical practice may experience personal conflicts with their superiors, colleges and patients. In fact, conflict management is an essential skill that nursing students must master. Pines and colleagues [6] added that nursing students did not have enough preparation to deal with interpersonal conflicts.

An understanding of nursing students’ conflict management style can provide insights on how to educate nursing students in the area of effective conflict management both during clinical experience and in their future as nurses. Positive conflicts experienced by students and nursing staff working in a clinical environment can inspire innovations and strategies to improve teamwork and patient care. This encourages the organization to achieve a high level of quality and achievement.

Studies related to the emotional intelligence of nursing students are essential for them to learn about emotional management during nursing work [7]. In a study which investigated emotional intelligence among nursing students, and related to stress, it was perceived as a coping strategy for nursing competence. Emotional intelligence was found to be positively associated with addressing specific problems and perceptions of nursing competence. Emotional intelligence was negatively associated with stress levels. High levels of control and emotional abilities help nursing students to adopt effective coping strategies when coping with stress situations, which mean that levels of burnout are lower [7]. The study highlighted the potential of emotional intelligence which enhances the students’ subjective well-being.

Burnout is a response to ongoing emotional pressures and depletion of the individual’s coping resources and occurs as a result of prolonged exposure to stress in work and life [8]. The central dimension of burnout is mental exhaustion that develops slowly after unsuccessful attempts to overcome negative stressors [9]. In contrast to stress, depression, or anxiety characterized by temporariness, burnout develops slowly, and does not disappear even after disengagement from the stressor [10]. Burnout can be also defined by three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and professional inefficacy. The process of burnout begins with gaps between the demands of the worker in his/her professional work and his/ her mental abilities and resources, and continues with a sense of distress, fatigue and mental restlessness, cynicism, and emotional detachment [11]. The term burnout expresses behavioral, social and physical changes that are manifested in professionals, especially in professionals who provide service to others, following sustained and intensive contact with service recipients. Research shows that workers who provide assistance in general and medical and mental health in particular are exposed to a high level of burnout in their work [12].

The causes of burnout are not dependent on the worker’s personality structure. However, there is a tendency in workplaces to combat the burnout phenomenon by selecting people with a personality that suits a specific profession. The problem of burnout usually touches on the organizational aspect. In order to deal with it, four dimensions must be addressed in the work environment; namely, the psychological, structural, social and organizational dimensions [13]. Burnout is not only caused by work stress or a stressful environment but is often caused by the way the individual works and responds to his/her environment. One of the recommendations how to prevent burnout is to slow down the pace of work, or to take regular work breaks and to avoid more hours of work. Other strategies include sharing emotional feelings, which can reduce stress and also clarify sources of frustration or distress. Social support can help prevent burnout [14]. New insights, personal rewards and recognition in social resources, can help reduce social isolation, and can also be a source of humor, optimism and encouragement in situations of difficulty.

The context of burnout among accredited nurses is not necessarily the same as for nursing students. It can be explained by the fact that, on one hand, nursing students have less responsibility than nurses and spend a short period in any clinical field. On the other hand, nursing students have to adapt to a new way of life. Many of them leave their homes and have to deal with the educational framework and to pass difficult exams, as well as to perform clinical work at healthcare institutes. Gray-Toft and Anderson [15] conducted a longitudinal study concerning nursing stress levels. Various dimensions were examined, like intelligence, morbidity, stress, coping, and burnout. The population was a group of nursing students who completed a questionnaire which measured stress and its relationship to the clinical field, and job satisfaction. The study found that at the end of the second year, the students learned to deal with the aspects of burnout. However, those who had a more open, daring, and liberal personality were more likely to experience burnout. In addition, students with introverted personalities suffered less from emotional exhaustion, which led to burnout. Second-year nursing students’ high burnout level can be explained by the fact that during their clinical work they were exposed to significant stressful situations, and therefore suffered emotional exhaustion that could lead to burnout. As the students progressed in their studies, responsibility and expectations in the clinical field increased, which had an influence on burnout.

Brotheridge and Lee [16] argued that burnout may occur due to preoccupation with intense work that prevents emotions. Slaski and Cartwright [17] found a negative correlation between emotional intelligence and stress. In addition, Gerits., et al. [18] found that nurses with high levels of emotional intelligence reported fewer signs of burnout than their counterparts who had lower intelligence levels.

Accordingly, it seems that the higher the levels of emotional intelligence are, the less signs of burnout, pressure and suicidal thoughts among nurses and students are found. Reducing sources of stress, burnout, and maintaining and fostering interpersonal relationships in a better way can lead to increased social support [19], which leads to less burnout among nurses [20]. Van Dusseldorp and colleagues [21] argued that it was important to introduce, develop and train emotional intelligence in the nursing education program to improve nurses’ level of emotional intelligence. The results of this study provide empirical evidence that raising emotional intelligence levels (such as the ability to manage positive and negative emotions and to control the efficacy of strong emotions) can benefit the occupational health of nurses, who experience high levels of stress, in that emotional intelligence helps reduce the development of burnout over time.

Increased levels of emotional intelligence can produce positive results at the individual level, such as improving or creating interpersonal relationships with patients and colleagues, increasing emotional coping resources, and increasing social support at work and at home because of good interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, increased levels of emotional intelligence can provide positive organizational results such as improvement in service delivery, reduced absences, commitment, and greater satisfaction [22].

Theoretical framework: A general model of burnout with major antecedents and consequences is the theoretical framework of this study [23]. According to this model, situations of over-demands such as workload, interpersonal conflicts, and lack of resources such as social support, coping mechanisms, skills, and autonomy lead to burnout, which is manifested in exhaustion and personalization. The cost of all this is reflected in diminished organizational commitment, turnover, absenteeism and physical illness.

Burnout is also a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, personalization, and personal reduction of achievement. Emotional exhaustion refers to the excessive use of emotions and the weakening of one’s emotional resources. The main sources of this exhaustion are demands such as workload and personal conflicts. People feel exploited without a source of innovation; they lack energy and have no ability to deal with another day or with the needs of the other person. De-personalization refers to a rigid negative expression or a detached reaction to other people that often involves loss of idealism. It usually develops in response to an overload of emotional exhaustion and is initially self-defense, but the risk is that detachment can become dehumanization. The personalization components represent the interpersonal dimension of burnout. Reduction in personal achievement refers to a decrease in feelings of productivity and efficiency at work. The decline in productivity in the sense of self-efficacy is associated with depression and inability to cope with job demands, and can be exacerbated by the lack of social support for opportunities of professional development. Personal achievement represents the self-esteem dimension of burnout. The three burnout components emerged from initial burnout studies based on surveys and interviews with a wide range of service personnel [24].

In summary, workload and personal conflicts are the main cause of burnout. Lack of resources such as coping, control, social support, use of skills and autonomy are seen as important sources of coping with burnout. When these resources are lacking, there may be burnout that begins with emotional exhaustion that leads to depersonalization, and the symptoms include sense of automation, and routine management of daily routine. The consequences of the most common burnout are various forms of job withdrawal that include decreased commitment, dissatisfaction, physical illness, and recurrent absences.

The main aim of this study was to examine the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among nursing students, and to examine whether additional variables like gender and religion related to the burnout phenomenon among nursing students. This research is important both for eliminating burnout, and for understanding the problem and trying to solve it. The research is also important in terms of organizational, economic and management areas, because when we know how to identity burnout factors, and what can be done to reduce it, we can profit both economically and organizationally because then employees work efficiently and produce better results. Many studies have been performed on burnout and its relationship to emotional intelligence in many professions (such as medicine, education and nursing). However, this study examined in depth the relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout among nursing students.

Hypotheses: Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Study design: A quantitative research was carried out in Israel among third- and fourth-year nursing students aged 21-33 years old.

Setting and sample: One hundred and twenty questionnaires were distributed in 4 colleges and universities throughout the country. A total of 102 questionnaires (85% response rate) were received.

Table 1: The study population.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of *** Center.

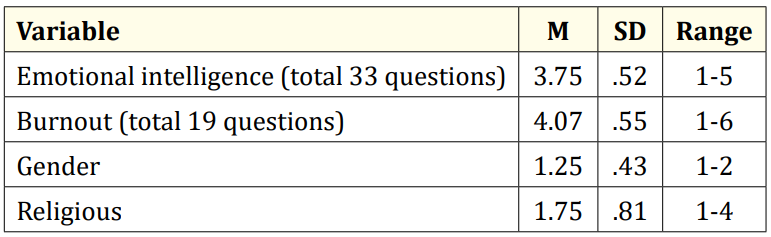

The emotional intelligence variable was measured using the SSEIT (Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test) [25], which was used in the Hebrew version translated and validated by GlickBower [26]. The SSEIT questionnaire includes 33 items that measure emotional intelligence. Each item was evaluated on a decision scale ranging from 1 ’strongly opposed’ to 5 ’strongly agree’. For example: ’I am aware of my feelings while I am experiencing them’. The items were encoded so that a high score indicated a high level of emotional intelligence. The original Cronbach’s α was 0.70-0.85. No questions were removed because none of the questions affected the internal consistency. Cronbach’s α reliability in the current study was 0.92.

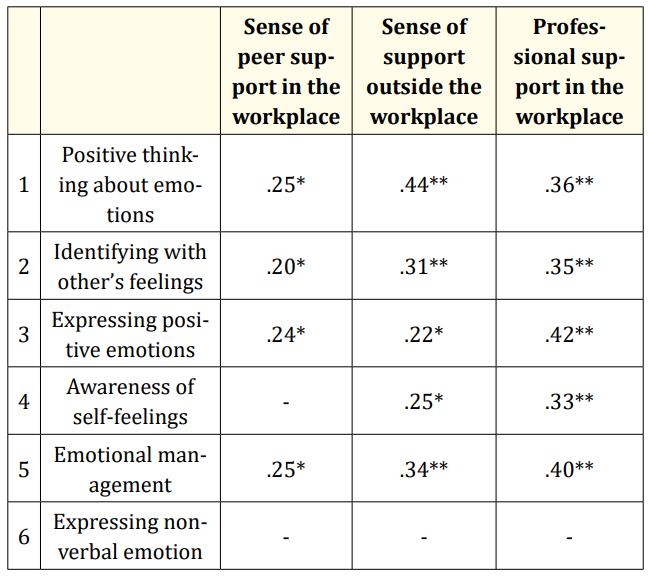

Six sub-levels of emotional intelligence and three sub-levels of burnout were grouped to test the correlation between the sublevels of both. Of the 33 emotional intelligence statements, six subgroups were built: positive thinking about emotions (for example, ‘I expect to succeed in most of the things I try to do’); identifying with others’ feelings (for example, ‘I can sense how people feel by listening to them’); expressing positive emotions (for example, ‘I look for activities that will please me’); awareness of self-feelings (for example, ‘I am aware of my feelings’); emotional management (for example, ‘I flatter others when they do something good’); and expressing non-verbal emotion (for example, ‘I am aware of the nonverbal messages I send to others’.

The burnout variable was measured using the BM-Burnout Measure written by 27 Pines and Aronson [27]. The questionnaire was translated into Hebrew by the author and was validated by two Israeli nurse professionals. The questionnaire included 24 items; each item was evaluated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 “ agree very much” to 6 “very opposed”. Example of item: ’I feel that my clinical instructor appreciates my work’. The items were encoded so that a high score indicated a lack of wear. The original Cronbach’s α was 0.91-0.93. Three items were removed due to non-relevant questions. The Cronbach’s α reliability in the current sample was 0.77.

2.Sense of support outside the workplace, for example ‘I share my difficulties with my relatives’; 3. Sense of professional support in the workplace, for example ‘I feel that my clinical instructor appreciates my work’Three sub-groups were built out of the 19 burnout measure statements: 1. Sense of peer support in the workplace, for example ‘I feel that my fellow students provide me with support when I need it’-; .

Table 2: Averages and SD of the research variables.

The researchers visited each class of 3rd and 4rd year students (BSN program in Nursing) and explained the purpose of the study. All participants signed an informed consent. Filling time for the questionnaire ranged from 15-20 minutes. All questionnaires were coded using only a part of the participant I.D. in order to keep student anonymity.

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS Frequencies: a multi-hierarchical regression, Pearson tests for correlation tests, and T-tests for testing differences between groups.

In order to test hypothesis H1, namely that a negative correlation would be found between nursing students’ emotional intelligence and burnout, a multi-hierarchical regression test was performed. It should be noted that according to our questionnaire, a high score indicates a lack of burnout and a low score indicates burnout. Significance was found [r² = 0.21, p =.046, F (4.93) = 6.00]. The hypothesis was confirmed, (p = .001), and the Beta was positive and significantly high (β =33). It was found that the higher the emotional intelligence, the lower the burnout.

In the second stage, correlations between sub-levels of emotional intelligence and sub-levels of burnout were tested. An interesting finding reinforced the significant correlation between emotional intelligence and burnout. Comparing the correlations between the five subgroups of emotional intelligence to the three subgroups of burnout, significant correlations were found between the subgroups, especially with professional support in the workplace and sense of support outside the workplace. The data are presented in table 3.

Table 3: Correlations between the subgroups.

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) :

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

To test hypothesis H2, namely that differences would be found between men and women’s burnout, a T- test was performed for independent samples. The hypothesis was indeed confirmed, there are differences between male and female nursing students’ levels of burnout [t (98) = 2.50, p =.049]. It was found that female students (4.15 ± 13.54) were less burned out than male students (3.83 ± 11.53).

To test hypothesis H3, namely that differences would be found between levels of burnout of Jewish and Arab students, a T-test was performed for independent samples. The hypothesis was confirmed; there are indeed differences between Jewish and Arab students’ levels of burnout [t (84) = 2.22, p =.05]. It was found that Jewish students (4.16 ± 11.58) were less burned out than Arab students (3.90 ± 15.48).

The main goal of this study was to examine the relationship between emotional intelligence and the level of burnout among third- and fourth-year nursing students for the degree of academic graduate nurse in Israel and gender variables in the sector. The question arose as a result of the clinical experience in hospitals and meetings with nursing students who experience pressure and stress in various health settings.

Three research questions were asked in this study. As part of the discussion, the results obtained from each hypothesis are analyzed, and the implications of these findings are discussed.

Hypothesis H1 was confirmed (p = .001), and the Beta was positive and significantly high (β = 33). It was found that the higher the emotional intelligence among nursing students, the lower their burnout, which is expressed by less self-perceptions of support. This study found that identification with the feelings of others, positive expression of emotions, alertness to personal feelings and emotional management are important factors that are significantly related to the students’ sense of support. These feelings were expressed by the sub-groups associated with support: their relationship with their peers, do they get support from the clinical instructors, and the sense of support they feel outside the clinical experience. These three subgroups of the support aspect are in fact the source of burnout, and it is therefore very important for us, the nursing educators, to be alert to this issue, and to find ways to make changes so that our students gain high sources of support, which is in turn directly related to a high level of emotional intelligence. The study’s findings also indicate that raising the level of emotional intelligence would result in low burnout feelings (i.e., high levels of support) [7,19,28-31].

Hypothesis H2 was confirmed, and differences were indeed found between male and female students’ levels of burnout [t (98) = 2.50, p = 0.044]. It was found that female students (M = 4.15, SD = .54) were less worn out than male students (M = 3.83, SD = .53). Women were less worn out than men because of support at work and out of work. It is expected that women would experience higher levels of burnout than men due to the general requirements of women and the constant demands of home and work. Women tend to be more burned out than men because women are usually married or mothers, and because of their high preferences for home care. Reinforcement for this explanation was found in Raggio and Malacarne [32], who studied the impact of the variables ‘professional role’ and ‘gender’ on the burnout syndrome. Compared to men, women showed turning to oneself as a defense mechanism, whereas men showed aggressiveness-anger. They concluded that the burnout syndrome was present in ICU healthcare workers and was significantly affected by operating role and gender. We must be aware of this phenomenon in order to study it and to reduce it.

It is also important to assume that nursing students who participated in our research did not feel the double burden of household management and professional demands combined. It is possible that beyond the variables of gender there are variables and other mediators that affect burnout, which have not been examined such as geographical location and multicultural societies. Another explanation for this finding is that the population of the study included only 26 males (25.5%) and this may have influenced the research’s results.

Hypothesis H3 was confirmed; differences were found between Jewish students and Arab students’ level of burnout [t (84) = 2.22, p =.032]. It was found that Jewish students (M = 4.16, SD = .58) were less worn out than Arab students (M = 3.90, SD = .48). Pines and Zaidman [33], claimed that Israeli Arabs were less likely to discuss emotional problems or use professional help, and more likely to use familial help. Israeli Jews were more likely to turn to a spouse, a friend, a professional, and a superior. It can be explained by the cultural diversity between Jews and Muslims. Each culture has its own characteristics that have impact on the students’ behavior concerning burnout, and on their emotional intelligence. The Muslim culture is more collective, and the Israeli Jews are more individualistic [34]. These differences are especially prominent in the ways they handle burnout.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the sample in our research is relatively small and includes 102 nursing students. Most of the students sampled are from the north of Israel, which could affect the results. It is possible that different research results would have been obtained had the sample contained a population from larger geographical locations. Second, the results of the study may be affected by the length of the questionnaire, the questionnaire contained 68 items.

In addition, the questionnaire was distributed to students during a stressful period of study. This could have caused the respondent to answer in an entirely unreliable manner. Another limitation that may affect the results is the scarcity of men in the study. Out of 102 participants, 25 participants declared themselves male. Therefore, there is no representative sample of the male population in order to reliably determine the level of burnout among nursing students based on gender. However, it is likely to have meaning.

In addition, most of the literature on which our research was based was taken from studies conducted in the world and not in Israel, which can affect the findings because these are different cultures.

The issue of burnout and its impact among nursing students and nurses is a relevant and important issue in Israel and around the world. There are not enough studies in the literature about burnout among nursing students. Therefore, it should be further explored. In follow-up studies, it is desirable to rely on larger and more diverse samples that include universities and colleges in a larger geographical location and focus on samples that represent men and women equally, in order to better understand the effects of gender on burnout levels and emotional intelligence. In addition, it is recommended to check whether burnout levels among nursing students are maintained with entry to work as a nurse; they may differ in various departments. It is also recommended to examine in depth how interpersonal relationships between students and staff in the various departments affect burnout levels.

The subject of burnout and its causes should be further investigated in order to reduce the damage caused by this phenomenon. This study has shown that emotional intelligence is very important in relation to burnout. There is a need to invest resources in the development and training of emotional intelligence in the nursing education programs in order to improve students’ emotional intelligence.

The direct conclusions of these findings are that it is recommended to carry out activities to identify early levels of burnout and emotional intelligence, and to conduct activities such as workshops and lectures for students to familiarize themselves with these areas and to receive tools for dealing with stress situations in their clinical experiences. Nurses’ emotional intelligence has been shown to be a protective factor against stress, and it could be especially important in training future professionals [30].

Increasing emotional intelligence skills can reduce burnout levels of nursing students, our future nurses. It would produce positive results at the individual level, such as improvement of interpersonal relationships with patients and colleagues, increased coping resources, and increased social support at work and at home because of good interpersonal relationships.

The authors declared that no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the nursing students who participated in this research.

Copyright: © 2020 Gonen Ayala and Grinberg Keren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.