Different Designs of Feeding Aids for Cleft Palatal Defects

Anshul Chugh1*, Divya Dahiya2, Harleen3, Sunita3, Anamika3 andAmit Dahiya4

1Associate Professor, Department of Prosthodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India

2Professor, Department of Prosthodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India

3Post Graduate Student, Department of Prosthodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India

4Senior Resident, Department of Orthodontics, Post Graduate Institute of DentalSciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India

*Corresponding Author: Anshul Chugh, Associate Professor, Department of

Prosthodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India.

Received: May 13, 2020; Published: June 16, 2020

Abstract

Cleft lip and palate is a congenital anomaly resulting in functional, esthetic and psychological disharmony of the patient. In infants, parents face a major problem in feeding them because of oro-nasal communication prior to any surgical intervention. In this article, various designs of passive feeding plates have been described to meet the nutritional demands of the infants. In young children, active feeding plates help in improving functioning along with the naso alveolar moulding.

Clinical Significance: This article presents various designs of passive and active feeding aids for nutritional needs of cleft lip and palate patients.

Keywords: Cleft Lip; Palate; Orofacial Region also initiation of swallowing itself (Wolf and Glass, 1992). Feeding

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate involving orofacial region are most common congenital anomaly. It can either be syndrome associated or non-syndromic. Cleft patients are associated with a lot of problems like, feeding difficulties, facial growth deficiency, dental, esthetic, psychological problems, velo-pharyngeal incompetence, otologic problems like middle ear infection, Eustachian tube dysfunction [1-3], delayed speech. These necessitate a multidisciplinary approach. But immediate concern for a newborn is feeding difficulty.

Feeding problems occurs because child is not able to create sufficient negative intraoral pressure (suction) during feeding. It also affects bolus organization, bolus retention before swallowing, and is further complicated by, nasal regurgitation, excessive air intake, and burping, coughing, choking and prolonged feeding causing fatigue [4-17].

A significant decrease was reported by Pandya and Boorman (2001) in failure-to-thrive rates for all infants with cleft palate, including syndromic cases after an early feeding program was implemented that involved growth monitoring, domiciliary visits, support of breast-feeding and feeding education. However, there is increasing emphasis on neonatal intervention that may include modified bottles and nipples, feeding plates, direct breast-feeding, and particular feeding techniques. But this management is insufficient if defect are large. Early surgical repair of the palate is a viable option. But usually it needs to be postponed until certain age and weight gain of the infant. Orogastric or nasogastric tube can be used but for limited time. In such patients, feeding obturator is a ray of hope [18-48].

Benefits of feeding obturator:

- Create rigid platform against which baby can press the nipple and extract milk.

- Help in creating negative pressure thus reducing regurgitation, choking and thus reduces time of feeding also.

- Help in proper tongue position thus preventing its interface in growth of palatal shelves and allowing functional development of jaw.

- Contribute to speech development.

- Reduces nasopharyngeal infection preventing food regurgitation in nasopharynx.

Materials and Methods

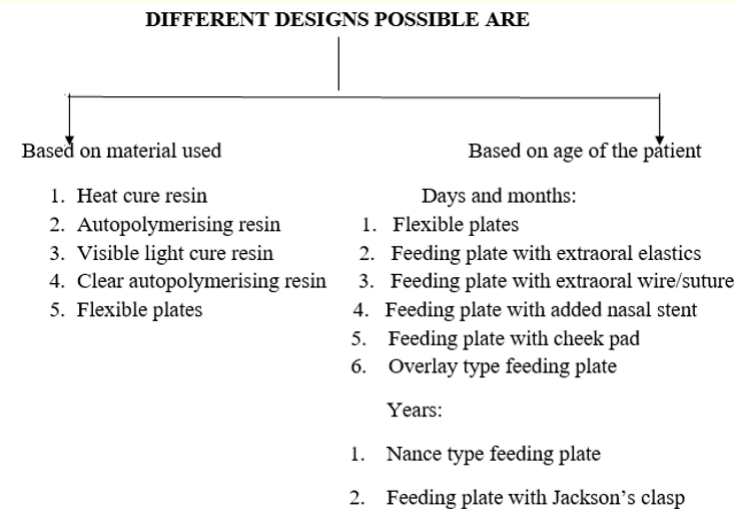

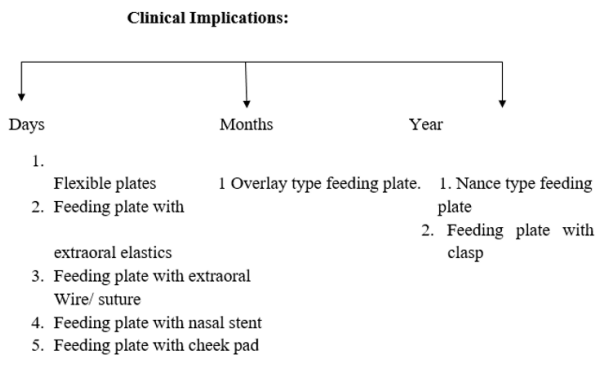

In this article we have fabricated various designs of the feeding plate. We are discussing the role of each design their merits and demerits.

Depending upon whether appliance places any force on alveolar

segment or not these can be grouped into (a) Active (b) Passive.

X

![]()

Passive plates

The passive plates do not apply any force, they serve to provide an artificial palate for the infant and permit functions like swallowing and feeding in a more normal manner. They also serve to prevent the widening of the cleft due to the activity of the tongue.

X

![]()

Results

Construction of feeding obturator in a day using autopolymerising resin and incorporation of dental floss to avoid gagging and accidental swallowing.

X

![]()

Fabrication of feeding obturator in a day using autopolymerising resin attaching two 18G orthodontic wire that extend out of mouth to avoid accidental ingestion or aspiration of obturator. Application of some acrylic resin at sharp end of wire to avoid injury to both child and parent.

Vacuum tray fabrication because of its added advantage over acrylic obturator of being mouldable and soft texture with less possibility of soft tissue injury, good fit to ridges and palate and light in weight. But these are not economical, and can cause irritation to palate.

X

![]()

X

![]()

X

![]()

X

![]()

Fabrication of pre alveolar nasal molding plate (PNAM) with heat cure clear acrylic resin with retentive acrylic button at 45 degree to occlusal plane in upward direction incorporation of stretchable extra oral elastic in retentive button in a hole that can be retained extraoraly with micropore.

Fabrication of pre naso alveolar molding plate with nasal stent using clear heat polymerized resin with a extraoral retentive button positioned at 45 degree to occlusal plane on labial flange facing downward. A wire added to upper end of button end of wire coated with permasoft to avoid injury to nasal soft tissue. Nasal cartilage molding is done by applying gentle pressure by activating wire loop.

Nance obturator can be used when it is not feasible to close fistula in palate surgically, and removable appliance is also not possible. It is a modified Nance space maintainer with a acrylic plate covering the defect. Advantage is it also acts as space maintainer and we need not to remake it with growth of maxilla.

X

![]()

Acrylic plate retained with clasp around teeth.

X

![]()

Implant retained and magnet retained plate also can be made.

Active appliances

- Latham’s appliance: It is a fixed appliance. It consists of two acrylic plates surgically fitted to palate under general anesthesia that are connected with a hinged bar posteriorly. Manipulation is done by rotating the hinged bar. In the area of the cleft a screw is present. The screw is turned 3/4th of a turn over 3 - 4 week period, every day until it is tight. It helps in repositioning of protruding premaxilla in bilateral cleft lip and palate patients, along with expansion of lateral maxillary segments. The advantage of this device is that it allows narrowing of defect by manipulating the palatal segments to desired location and thus make repair of cleft lip easy. Disadvantage is it does not cover the defect.

- Jackscrew appliance: This consists of two acrylic plates fitted over the alveolar segments and attached by single or multiple jackscrews. By adjusting the jackscrew the palatal segments can be manipulated to desired location. And jackscrew also prevents the interference of tongue in cleft closure.

X

![]()

Steps to be followed in fabrication of feeding plates

Step 1:

- Selection of the impression tray: size of impression tray should be enough to include maxillary segments laterally, cover up maxillary tuberosities posteriorly.

- Prefabricated trays also are also available commercially (Coe laboratories, Chicago) for cleft lip and palate infants.

Step 2:

- Making Primary impression. The making of the impression in an infant with a cleft palate is a critical procedure.

Step 3:

- Primary cast was fabricated with type III gypsum product (dental stone).

Step 4:

- Custom tray fabrication with autopolymerising resin.

Step 5:

- Final impression made with rubber base impression materials to record precise details.

Step 6:

- Master cast fabrication and excessive undercut blocking with modeling wax.

Step 7:

- Wax pattern adaption on master cast.

Step 8:

- Flasking, dewaxing procedure and feeding plate fabrication with heat cure acrylic resin.

Step 9:

- Eyelets created on feeding plate to allow silk suture to pass through.

- Various techniques are used to enhance retention of plate.

Discussion

Cleft lip and palate is congenital anomaly and it shows predilection for some races also. It may be syndromic or non-syndromic. The syndromic types are definition associated with other malformations like in Apert′s syndrome, Pierre Robin sequence, trisomies 13 and 18, Treacher Collin syndrome, Warrensburg’s syndrome, Stickler′s syndrome. Isolated cleft lip and palate defect is reported to occur in approximately 1 in 700 live births, Male to female ratio for cleft lip and palate predilection is 2:1. In unilateral clefts, clefts of left side are more common.

Different materials that can be used for impression are:

- Heavy body silicone impression material, polyvinyl siloxane impression materials, low fusing impression compound and alginate have been mostly used for making impressions of neonates with orofacial clefts.

- The bite registration materials, impression compound has also been in use for the impressions of infants with oral clefts.

- The putty wash impression has been known to produce accurate impressions with good reproduction of the details and its advantage is its greater tear strength and the possibility of making multiple casts from the same impression. Putty can be used with finger adaptation.

Complication encountered while making impression are:

- Engagement of impression in undercuts and its fragmentation during withdrawal causing respiratory obstruction/asphyxiation.

Precautions taken to avoid complications are:

- Impression should be made when the infant is fully awake

- Impression should be made in proper hospital setting with a surgeon present all the time to handle airway emergency.

- Maintaining airway patency by depressing tongue with mouth mirror.

- Clean remnants of impression material after the procedure.

- Infant has not had food for at least two hour before proceure. High volume suction should be ready at all times, in case of aspiration of gastric content.

- Maintain a proper patient and dentist position. A number of positions including prone, face down, upright, and even upside down have been adopted.

Summary and Conclusion

Adequate knowledge of available treatment modalities, procedures and appliances leads to a better coordination and understanding of the efforts of the various specialties which are involved in cleft lip and palate care. A basic knowledge of possible complications and their management makes us better equipped in handling emergencies if they arise. This article describes various possible designs of feeding obturator for a cleft palate baby. Feeding obturator promotes weight gain of neonates and help in preparing the baby for corrective surgery.

Bibliography

- Sujoy Banerjee., et al. “Pre-surgical management of unilateral cleft lip and palate in neonate. A clinical report”. The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society 11 (2011): 71-76.

- R Narendra., et al. “Feeding obturator- A presurgical prosthetic aid for infants with cleft lip and palate Clinical report”.

- M Rathee., et al. “Role of Feeding Plate in Cleft Palate: Case Report and Review of Literature”. The Internet Journal of Otorhinolaryngology (2010): 1.

- Ravichandra KS., et al. “A new technique of impression making for an obturator in cleft lip and palate patient”. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 4 (2010):311-314.

- Narendra R., et al. “Feeding obturator - a presurgical prosthetic aid for infants with cleft lip and palate - clinical report”. Annals and Essences of Dentistry 2 (2013): 1-5.

- Sikligar S., et al. “A ray of hope in cleft lip and palate patients: case reports”. European Journal of Dental Therapy and Research2 (2014): 217-220.

- P Chandna., et al. “Feeding obturator appliance for an infant with cleft lip and palate”. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 29 (2011): 71-73.

- Chandna P., et al. “Feeding obturator appliance for an infant with cleft lip and palate”. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 1 (2011): 352-355.

- Hodgkinson PD., et al. “Management of children with cleft lip and palate: a review describing the application of multidisciplinary team working in this condition based upon the experiences of a regional cleft lip and palate centre in the united kingdom”. Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review1 (2005):1-27.

- Rivkin CJ., et al. “Dental care for the patient with a cleft lip and Part 1: From birth to the mixed dentition stage”. British Dental Journal 188.2 (2000): 78-83.

- Akulwar R. “Feeding Plate for The Management of Neonate Born With Cleft Lip and Palate”. International Journal of Science and Research 10 (2014): 362-364.

- Savion I and Huband ML. “A feeding obturator for a preterm baby with Piere Robin sequence”. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 93 (2005): 197-200.

- McDonald R., et al. “Dentistry for the Child and the Adolescent”. 8th Edition St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby (2004).

- Murray JC. “Gene/environment causes of cleft lip and/or palate”. Clinical Genetics 61 (2002): 248-256.

- Osuji OO. “Preparation of feeding obturators for infants with cleft lip and palate”. The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry 19 (1995): 211-214.

- Sheahan P., et al. “Incidence and outcome of middle ear disease in cleft lip and/or cleft palate”. International Journal of Pediatric o t o r h i n o l a r y n g o l o g y7 (2003): 785-793.

- Jones JE., et al. “Use of a feeding obturator for infants with severe cleft lip and palate”. Special Care in Dentistry 2 (1982):116-120.

- Choi BH., et al. “Sucking efficiency of early orthopaedic plate and teats in infants with cleft lip and palate”. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 20 (1991): 16769.

- Shprintzen RJ. “The implications of the diagnosis of Robin sequence”. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal: SAGE Journals 29 (1992): 205-209.

- Samant A. “A one-visit obturator technique for infants with cleft palate”. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 47 (1989): 53940.

- Kernahan DA and Stark RB. “A new classification system for cleft lip and cleft palate”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 5 (1958): 441.

- John A Foote. “Malnutrition in infants with cleft palate: with a description of a new external obturator”. The American Journal of Diseases of Children 3 (1925): 343-346.

- Turner L., et al. “The effects of lactation education and a prosthetic obturator appliance on feeding efficiency in infants with cleft lip and palate”. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 38 (2001): 519-524.

- Oliver HT. “Construction of orthodontic appliances for the treatment of newborn infants with clefts of the lip and palate”.American Journal of Orthodontics 56 (1969): 468-473.

- Gupta R., et al. “Fabricating feeding plate in CLP infants withtwo different material: A series of case report”. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 4 (2012):352-355.

- Shahapur S., et al. “Prosthetic Management of Nasoalveolar Clefts in Newborns: A series of case report”. The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society 11 (2011): 2503.

- Mustafa Erkan., et al. “A Modified Feeding Plate for a Newborn with Cleft palate- A Case Report”. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal1 (2013): 109112.

- Duggal A., et al. “Feeding obturator appliance in a cleft palate patient: A case report”. Indian Journal of Comprehensive Dental Care 1 (2014): 64-67.

- McDonald R., et al. “Dentistry for the Child and the Adolescent”.8th Edition St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby (2004).

- Goldberg WB., et al. “Successful use of a feeding obturator for an infant with a cleft palate”. Special Care in Dentistry 8 (1988):86-89.

- Chandna P and Adlakhavk Singh. “Feeding obturator appliance for an infant with Cleft lip and palate”. Journal of Indian society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry1 (2011): 71-73.

- Dean J., et al. “McDonald’s and Avery’s dentistry for the child and adolescent Mosby/Elsevier”. Mosby/Elsevier (2011).

- Vojvodic D and Jerolimov P. “The cleft palate patient: a challenge for prosthetic rehabilitation--clinical report”. Quintessence International 7 (2001): 521-524.

- Sala Marti S., et al. “Prosthetic assessment in cleft lip and palate patients: a case report with oronasal communication”. Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral Y Cirugia Buccal 6 (2006): 493496.

- Reisberg DJ. “Dental and Prosthodontic Care for Patients With Cleft or Craniofacial Conditions”. American College Personnel Association 6 (2000): 534-537.

- DR L. Presurgical orthopedic therapy for cleft lip and palate.

- Jacobson BN and Rosenstein SW. “Early maxillary orthopedics for the newborn cleft lip and palate patient. An impression and an appliance”. The Angle Orthodontist 3 (1984): 247-263.

- “Cleft Lip and palate”. Berlin: Springer (2006).

- Raffat A and Ijaz A. “Premaxillay retraction in bilateral complete cleft lip and palate with custom made orthopaedic plate having anterior acrylic ring”. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association 6 (2009): 376-380.

- Uzel A and Alparslan ZN. “Long-term effects of presurgical infant orthopedics in patients with cleft lip and palate: a systematic review”. American College Personnel Association5 (2011): 587-595.

- Grayson BH., et al. “Presurgical Nasoalveolar Molding in Infants with Cleft Lip and Palate”. American College Personnel Association 6 (1999): 486-498.

- Grayson BH and Shetye PR. “Presurgical nasoalveolar moulding treatment in cleft lip and palate patients”. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery 42 (2009): 56-61.

- Papadopoulos MA., et al. “Effectiveness of pre-surgical infant orthopedic treatment for cleft lip and palate patients: a systematic review and metaanalysis”. Orthodontics and Craniofacial Research (2012).

- Goodacre T and Swan MC. “Cleft lip and palate: current management”. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 4 (2012).

- Shah CP and Wong D. “Management of children with cleft lip and palate”. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1 (1980): 19-24.

- Sujoy Banerjee Usha M Radke., et al. “Pre-Surgical Management of Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate in a Neonate: A Clinical Report”. The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society 11 (2011):71-76.

- Goldberg WB., et al. “Successful use of a feeding obturator for an infant with a cleft palate”. Special Care in Dentistry 8 (1988):86-89.

- Osuji OO. “Preparation of feeding obturators for infants with cleft lip and palate”. The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry 19 (1995): 211-214.