Catherine Grace Q1 Aparece and Anabella S2 Oncog*

Department of Pediatrics, Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital, Philippines

*Corresponding Author: Anabella S Oncog, Department of Pediatrics, Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital, Philippines

Received: November 11, 2019 Published: November 27, 2019

Citation: Catherine Grace Q Aparece and Anabella S Oncog. “Treatment Failure Rate of Penicillin Gas Empiric Therapy for Pediatric Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children Admitted in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.12 (2019): 55-65.

Background: Pneumonia remains the leading cause of death among children under five. Antibiotic therapy is the mainstay of treatment for children with pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Empiric penicillin therapy has been recommended by the Philippine Academy of Pediatric Pulmonologists, Inc. (PAPP). There has been no local study yet on the treatment failure or cure rate of penicillin therapy in pediatric community acquired pneumonia (PCAP).

Objective of the study: To determine the failure rate of penicillin therapy among children with community acquired pneumonia admitted to Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital (GCGMH).

Methodology: This is a prospective descriptive study on children 2 to 59 months old who were admitted to the pediatric wards of GCGMH for PCAP. Approval to conduct the study was granted by the hospital institutional review board. All eligible children were followed up from admission to discharge. Data gathered included clinicodemographic profile like age, gender, duration of breastfeeding, primary caregiver’s educational level, smoker in the household, family member with cough, and nutritional status; change of antibiotic from penicillin to another antibiotic because of treatment failure. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the clinicodemographic profile of patients treated with penicillin G. Chi-square test for association was performed to determine the relationship between clinicodemographic profile and treatment failure of penicillin G. Significance was confirmed for p-value of <0.05.

Results: There was a total of 277 patients with PCAP who were admitted to GCGMH from November 1, 2018 to April 30, 2019. Most of these patients were infants 12 months and younger and were males. More than 75% of these children were breastfed longer than 3 months. Only 1 of these patients received less than 3 doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and Hemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. Majority of these children’s primary caregivers attained secondary education level. A smoker in the household was present in 96.4% of cases and a household contact with cough was present in 97% of cases. More than half of the cases were well-nourished and 2.89% had severe wasting. Eleven percent of these children did not respond favorably to penicillin and therapy was changed to another antibiotic. Correlation tests between the clinicodemographic profile of patients and their response to penicillin G showed that there is a positive correlation only between nutritional status and response to penicillin G (p-value <0.009).

Conclusion: The failure rate of penicillin G therapy in children hospitalized with community acquired pneumonia is 11%. Only the child’s nutritional status impacts the response to penicillin G. Children with severe wasting are less likely to respond favorably to penicillin G compared to children who are better nourished.

Keywords: GCGMH; Children; Penicillin G

Pneumonia remains the leading cause of death among children under five, killing approximately 2,400 children a day. It accounted for approximately 16% of the 5.6 million under-five deaths, killing around 880,000 children in 2016 [1]. It was estimated that more than 150 million episodes of pneu- monia occur annually in under five years age group in developing nations [2]. The Philippines, a developing country in the Western Pacific Region, has an estimated incidence rate of pneumonia in children less than 5 years of age of 110 per 1000 person-years [3]. It is one of the 15 countries that together account for 75% of child- hood pneumonia cases worldwide [4]. Local statistics have shown that pneumonia is a major cause of pediatric morbidity in this hospital. In 2017, it topped the leading causes of morbidity. There were 1659 cases of PCAP-C, making up 38% of the total pediatric discharges. Antibiotic therapy is the mainstay of treatment for children with pneumonia requiring hospitalization. The choice of antibiot- ics for hospitalized children with community-acquired pneumonia is usually empiric, based on clinical and radiologic findings and knowledge of the etiology of the pneumonia at different ages. Pneumonia etiology varies by age, underlying conditions, geo- graphic location, vaccine exposure and seasonality. An accurate etiologic diagnosis is often complicated and differentiating be- tween bacterial and nonbacterial pneumonia is clinically difficult. Current evidence suggests severe pneumonia results from infec- tion with multiple pathogens such as bacterial-viral, dual viral, or mycobacterial-bacterial infections [5]. It has been reported that up to a third of children with pneumonia may have viral-bacterial co- infections [6]. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenzae tybe b (Hib) are the two principal causes of pneumonia. Streptococcus pneumoniae causes up to 18% of severe cases and 33% deaths, followed by Hib that causes 4% of severe episodes and 16% of deaths, and finally, by influenza virus that causes 7% of severe epi- sodes and 11% of deaths [7]. The predominance of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hib is common in both developed and developing countries. In Tanzania, a study showed that Streptococcus pneu- moniae topped the list of microbiological findings in children with pneumonia, followed by Hib [8]. A study conducted in Cambodia also showed a high frequency of Hemophilus influenzae and Strep- tococcus pneumoniae [9]. A Finnish study conducted in 2012 also revealed that Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hemophilus influen- zae were the most common bacteria in children with community- acquired pneumonia [10]. The risk of pneumonia and of pneumonia hospitalization has been shown to be associated with age, maternal history of pneumo- nia, cigarette smoking, and a crowded household [11]. Additional risk factors were also reported by Bersam., et al. and these include maternal education < 8 years, child’s birth order, and prenatal com- plications [12]. Malnutrition has also been consistently shown to be a risk factor for pneumonia [13-16]. The Philippine Academy of Pediatric Pulmonologists (PAPP), Inc., a society of pediatric pulmonologists in the country, came up with a revision of the 2004 Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) on pediatric community acquired pneumonia on 2016. The revisions were mostly on the criteria for the risk classification for pneumo- nia-related mortality. The guidelines remained steadfast on the rec- ommendation that for patients who have been classified as PCAP C without previous antibiotic and have completed the primary im- munization against Hemophilus influenzae type b, penicillin may be given [17]. This recommendation to give penicillin as empiric therapy for community-acquired pneumonia in children has been based on several studies. One of the studies was conducted by Dinur- Schejter., et al. in 2013. They compared treatment failure and the number of patients who were febrile and who required oxygen 72 hours after admission between patients who were given penicillin or ampicillin and patients who were given cefuroxime. They found out that there was no significant difference in these endpoints between the two groups. Thus, they concluded that in previously healthy children, parenteral penicillin or ampicillin for treatment of non-complicated community-acquired pneumonia is as effective as cefuroxime and should remain as first-line therapy [18]. Another study was conducted by Amarilyo., et al. in 2014. In this study, they hypothesized that community-acquired pneumo- nia requiring parenteral medication can still be cured with penicil- lin G. After a prospective, randomized study comparing low-dose penicillin G, high-dose penicillin G, and intravenous cefuroxime, they found out that the children recovered at the same rate with no significant difference in time to defervescence or duration of hospitalization. They concluded that penicillin G is as effective and safe as cefuroxime for community acquired pneumonia in other- wise healthy children, even in moderate doses [19]. The effectivity of penicillin monotherapy has also been dem- onstrated in a study conducted in Kenya. The authors compared the effectiveness of penicillin to that of a combination of penicil- lin and gentamicin in children characterized by indrawing. They concluded that there was no statistical difference in the treatment of indrawing pneumonia with either penicillin or penicillin plus gentamicin [20]. The department of pediatrics of Gov. Celestino Gallares Memo- rial Hospital (GCGMH) has followed the guidelines since their dis- semination. In fact, the department has long been using penicillin following the World Health Organization program for the control of acute respiratory infections [21]. The hospital antibiogram in the last half of 2017 specific for pediatric patients, unfortunately has not been able to show a sig- nificant proportion of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenzae. Hence, the antibiogram could not be used as basis for empiric therapy of pneumonia in pediatric patients. Moreover, no local study has recently been conducted yet on the treatment fail- ure or cure rate of penicillin therapy in pediatric community ac- quired pneumonia; thus, this study was proposed.

This study is believed to benefit the following stakeholders:

To determine the failure rate of penicillin therapy among chil- dren with community-acquired pneumonia admitted to Gov. Celes- tino Gallares Memorial Hospital.

This will be reflected in the data as non-responder to penicillin G.

This is a prospective descriptive study.

This study included all children 3 to 59 months old who are ad- mitted to the pediatric wards of Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia.

Data gathering commenced on November 1, 2018 and ended on April 30, 2019.

This study utilized total population enumeration.

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the clinicodemo- graphic profile of patients treated with penicillin G. These included construction of frequency and percentage distribution tables. Chi- square test for association was performed to determine the relationship between clinicodemographic profile and treatment fail- ure of penicillin G of the patients. Significance was confirmed for p-value <0.05. All data analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0.

There was a total of 277 patients with community-acquired pneumonia who were admitted and who were included in the study. Based on the data shown in Table 1, most of the PCAP patients who were treated with Penicillin G were infants 12 months and younger and were males. More than 75% of these children were breastfed longer than 3 months. Only 1 of these patients received less than 3 doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and He- mophilus influenzae type b vaccine. Majority of these children’s primary caregiver attained secondary education level. A smoker in the household was present in 96.4% of cases and a household contact with cough was present in 97% of cases. More than half of the cases of children with PCAP were well-nourished, and 2.89% of cases had severe wasting

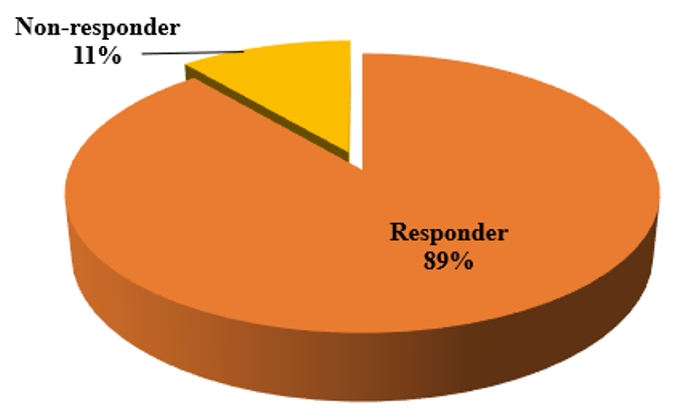

Figure 1: Percentage Distribution of Patients with PCAP Based on Response to Penicillin G.

Eighty-nine percent of PCAP patients responded favorably to Penicillin G, and 11% were non-responder to Penicillin G. Correlation tests between the clinicodemographic profile of PCAP patients and their response to Penicillin G showed that there is a positive correlation between nutritional status and the response to Penicillin G, which was highly significant with p-value of 0.009 (r = |0.200|). There was no correlation noted between the response to Penicillin G and age, gender, duration of breastfeed- ing, pneumonococcal and H. influenzae immunization status, edu- cational level of the primary caregiver, presence of smoker in the household as well as presence of household contact with cough.

Table1: Clinicodemographic Profile of Patients with PCAP and Treated with Penicillin G.

Table 2: Association Between Clinicodemographic Profile and Response to Penicillin G.

Pneumonia remains one of the leading causes of morbidity in Gov. Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital. Hospital statistics showed that there were 562 children who were admitted for pneumonia from November 1, 2018 to April 30, 2019. Of these, 277 children (49.2%) were given penicillin G as empiric therapy.

This study showed that more than 2/3 of the children admitted for pneumonia were infants aged 3 to 12 months. This finding is similar to that reported in the study of Le Roux., et al. who followed mother-infant pairs in Paarl, South Africa up to 1 year of age. They found out that pneumonia is high in the first year of life in this South African birth cohort despite strong immunization program that included 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [23]. This finding is indirectly similar to an old study by Leowski who estimated from data from 39 countries that there are more deaths per year from pneumonia among infants 0 – 1 year old (2.6 million) than among children 1 to 4 years old (1.4 million) [24].

This study showed that more male than female children were admitted for pneumonia. Le Roux’s study also showed that the male sex is one of the strongest risk factors for pneumonia. This may possibly be because of gender-related differences in immune or inflammatory responses [25,26], or differences in lung structure or function [27]. Casimir., et al. showed in their study of 482 children that the median C-reactive protein concentration in girls was significantly higher than in males, i.e., 5.45 mg/dL vs. 2.6 mg/ dL (p < 0.0001); the median erythrocyte sedimentation rate was also significantly higher in female children than in male children, i.e., 39.5 mm /h vs. 24 mm/h (p < 0.005); and the median neutrophil count was also significantly higher for girls than for boys, i.e., 8796 cells/uL vs. 6774 cells/uL (p < 0.02) [25]. A study conducted by Yang., et al. on mice identified a critical role for estrogen-mediated activation of lung macrophage nitric oxide synthase-3 (NOS3), thus explaining why females are more able to fend off pneumonia. The role of estrogen was affirmed when treating the male mice with estrogen resulted in a boost in their immune system’s ability to kill off bacteria in their lungs [28].

This study showed that more children who were breastfed longer than 3 months were admitted for pneumonia. This seems to contradict the finding of Bersam., et al. who reported that breastfeeding >3 months is a protective factor against pneumonia [11], and the systematic literature review and meta-analysis conducted by Lamberti., et al. in 2013 that highlighted the protective effects of breastfeeding against pneumonia incidence, prevalence, hospitalizations, mortality and all-cause hospitalizations and mortality in children under 2 years old [29]. Furthermore, the study by Le Roux., et al. also showed that breastfeeding duration was not a significant factor affecting the incidence of pneumonia in children [23].

An overwhelming majority of children admitted for pneumonia had completed the primary series of the pneumococcal and the Hemophilus influenza b (Hib) vaccines. This finding contradicts the reports touting the effectiveness of these vaccines. In a meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials, it was shown that the efficacy of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) for preventing vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in children

Majority of the children who were admitted for pneumonia had mothers who reached secondary level of education. This finding is consistent with that reported by Bersam., et al. i.e., maternal education < 8 years is a risk factor for pneumonia [11]. Other studies have also reported that low educational levels of mothers are a major risk factor for pneumonia in children under 5 years of age [23,35,36]. This may possibly be related to lack of or inadequate knowledge on pneumonia. The authors think that this may be a venue that needs to be addressed in order to prevent pneumonia or mitigate the morbidity and mortality from pneumonia.

Ninety-six percent of the children admitted for pneumonia lived in a household which has a resident smoker. Exposure to cigarette, especially if the mother smokes, has been reported to increase the risk of pneumonia in infants younger than 1 year old [37]. Le Roux also reported that maternal smoking is one of the strongest risk factors for pneumonia [23]. A study conducted in Mexico even reported that children exposed to environmental tobacco smoke has more than threefold increased risk of developing pneumonia [38]. This may be because cigarette smoke compromises natural pulmonary defense mechanisms by disrupting both mucociliary function and macrophage activity [39].

Exposure to a household contact with cough was apparent in the majority of children admitted for pneumonia. This highlights the transmission of the etiologic agents through air-borne droplets from a cough or sneeze [40] and the critical role of the observance of at least the cough etiquette [41] in the reduction of transmission of the causative agents of pneumonia.

More than half of the children admitted for pneumonia were well-nourished, and a quarter of the subject population were mildly wasted. Severely wasted children accounted for only 2.89% of cases. This finding differs from that of Rahman., et al. who reported that respiratory illnesses with fever or cough were more frequent in Bangladeshi children with moderate or severe wasting [42]. Severe underweight was also seen to have a positive association with pneumonia incidence in South African infants [23]. Similarly, 25% of Kenyan children who were admitted for severe pneumonia were severely undernourished [43]. The authors can only postulate that the significant deviation of the finding in this study from that of published articles may be attributed to the sampling methodology. This study included only pneumonia patients treated empirically with penicillin. Severely wasted patients tend to have more severe pneumonia that require more aggressive empiric antibiotic use, thus were excluded from the study.

Majority of the children admitted for pneumonia responded favorably to penicillin. Only 11% of them required change to a second line antibiotic for apparent non-responsiveness. This finding is similar to the result of the study conducted by Simbalista., et al. who reported that penicillin G successfully treated 82% of children hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia. They further reported that children in the penicillin G group showed marked improvement of symptoms, including fever, tachypnea, chest indrawing, and nasal flaring [44]. In relation to this, comparative studies between penicillin which is a narrow-spectrum antibiotic and cephalosporins like cefuroxime, cefotaxime and ceftriaxone which are broad-spectrum antibiotics showed that penicillin is as effective as the broad-spectrum antibiotics [18,19,45,46]. The results of all these studies suggest that penicillin should remain the first choice of therapy for children hospitalized with pneumonia.

Correlational studies between the clinicodemographic features of the subject population and the response to penicillin showed that all the clinicodemographic features, except the nutritional status, have no effect on response to penicillin. These findings differ from the findings in the studies by Addobo-Yobo., et al. and Tiewsoh., et al. who demonstrated that younger age, breastfeeding, and immunization status, as well as previous use of antibiotics, overcrowded home, and higher respiratory rate are independent predictors of possible treatment failure [47,48].

This study showed that only the nutritional status of the patient is related to response to penicillin. This indicates that the severely wasted patients are less likely to respond to penicillin as compared to the better nourished patients. Several studies have shown how malnutrition can increase the frequency and severity of infectious diseases. However, the author could not find any article that fully explains how malnutrition promotes treatment failure of penicillin in community-acquired pneumonia. One factor that may explain the higher therapeutic failure rate of penicillin in severely wasted children is that Streptococcus pneumoniae has been found to be a less frequent etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in severely malnourished patients. In a systematic review on pneumonia in severely malnourished children in developing countries conducted by Chisti., et al. it was demonstrated that Streptococcus pneumoniae accounted for only 18% of all cases of pneumonia in severely malnourished children. Overall, the most commonly isolated organisms in severely malnourished children with pneumonia were, in decreasing frequency, Klebsiella species (26%), Staphylococcus aureus (25%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (18%), Escherichia coli (8%), Hemophilus influenzae (8%), and Salmonella species (5%). The remaining proportion consists of other organisms like Acinetobacter species, Pseudomonas species, Moraxella species, and Enterobacter species [49].

Treatment failure in severely amalnourished children hospitalized for pneumonia may also be due to superinfection [50] or nosocomial bacteremia [51]. In a study in Kilifi District Hospital in Kenya, it was reported that severe malnutrition was significantly associated with nosocomial bacteremia, with a hazard ratio of 2.52. The authors defined nosocomial bacteremia as bacteremia that occurred after 48 hours or more of admission. Thus, empiric penicillin therapy may fail as it is a narrow spectrum antibiotic and will not be effective against organisms causing nosocomial infection.

The failure rate of Penicillin G therapy in children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia is 11%. Only the child’s nutritional status impacts the response to Penicillin G. Children with severe wasting are less likely to respond favorably to Penicillin G compared to children who are better nourished.

Based on the results of this study, the author recommends that:

Copyright: © 2019 Catherine Grace Q Aparece and Anabella S Oncog. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.