Agbeille Mohamed F1*, Adedemy JD1, Noudamadjo A1, Agossou J1, Kpanidja MG1, Aisso U1, Biaou COA2, Seydou L1 and Koumakpaï-Adeothy S3

1Mother and Child Department, Faculty of Medicine, University of Parakou, Benin

2Regional Institute for Public Health, Benin

3Honorary Professor of Pediatrics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin

*Corresponding Author: Agbeille Mohamed F, Mother and Child Department, Faculty of Medicine, University of Parakou, Benin.

Received: October 31, 2019; Published:November 19, 2019

Citation: Agbeille Mohamed F., et al. “Five-Years Survival Trends and Outcomes among HIV-Exposed Children Follow up in a Northern Benin Tertiary Facility”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.12 (2019):41-48.

Introduction: HIV prevention emergence has significantly helped in reducing the risk of Mother-to-child transmission. This work is aimed at determining the survival rate at 5 years of HIV-exposed children follow up in the pediatric unit of Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital in Northern Benin Republic.

Patients and Methods: It was a descriptive cohort study with an analytical purpose covering five years from 2011 to 2016. It involved 121 HIV- exposed children. Kaplan-Meier method was used to make an estimation of survival probabilities. Survival trends were compared with Log-rank test. Cox regression test was used to identify the factors associated with child deaths.

Results: On inclusion, the mean age for children was 35 days ±6 days and sex ratio estimated at 1.58. Survival rate at 5 years was 81%. Survival probability at 18 months and 60 months was 0.8264 and 0.8099, respectively. Deaths involved 23 children (19%). Factors associated with deaths were maternal age between 20 and 25 years (p=0.024), trade as mother’s profession (p<0.01), irregular follow-up (p<0.001) and positive PCR (p<0.001).

Conclusion: In order to ensure better survival of HIV-exposed child, it is necessary to improve PMTCT quality.

Keywords: Survival; Exposed Child; HIV; PMTCT; Benin

Vertical transmission is one of the most serious tragedies induced by HIV epidemics, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 90% of new infections occur [1]. Although the global objective of HIV elimination till 2015 has not been achieved in all the areas of the world, huge progress has been made over recent decades in the reduction of mother to child transmission (MTCT). According to the World Health Organization, 80% of pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV have had access to antiretroviral therapy in 2017 [2]. Thanks to good prevention availability of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) services providing effective responses, the global HIV transmission rate may be reduced to a rate close to 1% among the breastfeeding women and to less than 1% among nonbreastfeeding women in developing countries [3,4]. If significant progress has been made in the reduction of MTCT, the survival of exposed children remains a serious concern. In this regard, many authors suggested higher risk mortality among those children [1,5]. Since 2012, Benin has taken action in eliminating MTCT. The residual risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV is currently estimated at 6.2% at national level [6].The pediatric unit of Borgou/ Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital in Northern Benin has been carrying PMTCT activities since 2005 with an ever-rising active population of exposed children. After more than a decade of activity, the authors focused on the survival at 5 years of HIV-exposed children and its associated factors.

This work is a descriptive and analytical cohort monitoring study. The survey was carried out over a three-month period running from April 1 to June 30, 2017. It involved children born to HIV-positive mothers followed up within the framework of PMCT in the pediatric unit of Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital between January 2010 and December 31, 2011, and who have reached 5 years of age.

The software EPIDATA version 3.1fr was used to enter the data; the latter was processed and analyzed using the software STATA version 11. Ratios and proportions were calculated for qualitative variables. Average and standard deviation were calculated for quantitative variables, the distribution of which was normal.

To synthesize survival probabilities according to follow-up number of months, we used the survival analysis method. For instance, investigated event was death and investigated time was duration of life after birth (in months). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to make an estimation of instantaneous survival probabilities, and survival curves were compared with Log-Rank test. Modeling was performed in accordance with Cox regression model to identify the factors associated with death of HIV-exposed children. The model was developed according to a step-up top-down approach based on p-value. For instance, the variables p-value of which was ≤ 0.25 in univariate analysis had been integrated into the initial model and those with higher p-value had been removed from the model at each step. The variables retained in the final model were those with p-value < 0.05. Relative Risks (RR) were calculated using Cox model but their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and p-values were determined using Wald test. Final model adequacy was verified using proportional hazard test.

Parents’ written informed consent was obtained before administering the questionnaire. Moreover, the parents of respondent children have been reassured concerning the anonymity and confidentiality of collected information. For this purpose, the use of digits as identification marks of survey forms was adopted. The authorization decision of the Ethics Committee of the University of Parakou has been issued and notified under No. 0013/CLERBUP/P/SP/R/SA/17.

A total of 121 exposed children were included in this study.

The mean age for exposed children was 35 days ±6 days on inclusion in the active population, with extremes ranging from 1 to 120 days. The sex ratio was estimated at 1.58. The mean age for their mothers was 27.5 years ± 4.8 years, with extremes ranging from 18 years to 40 years. 25-30 year age group was the predominant one (43%).

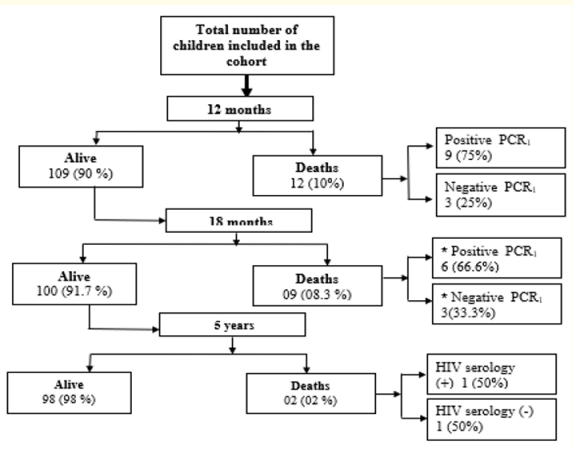

Among the 121 included children, 100 were alive at 18 months of age and 98 had reached their fifth birthday (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow diagram showing the children included in the cohort between 2010 and 2011 and their outcome at 5 years of age. *All the children dead between 12 and 18 months had benefitted from PCR. At 18 months of age, only one child had HIV serology; the others died earlier.

Within the study cohort, the survival rate at 5 years of age was 81% (98/121). Deaths involved 23 children and 10% of them were dead before 12 months of age. The mortality rate of children integrated in the cohort was 19% (23/121). 21 (91.4%) of those deaths occurred before 18 months of age (21/23). As well, 16 (69.5%) among the dead children were HIV-infected (16/23) with positive PCR at 6 weeks of life and 7 (30.5%) had negative PCR (7/23). Among the 16 deaths of infected children, 15 (93.8%) occurred before 18 months of life (15/16). 6 out of the 7 dead children with negative PCR died before the age of 18 months, and those children did not benefit from HIV serology. The only child that died after 18 months of life was HIV-negative. At five years of age, 98 exposed children were alive, including 96 uninfected and 2 HIV-infected.

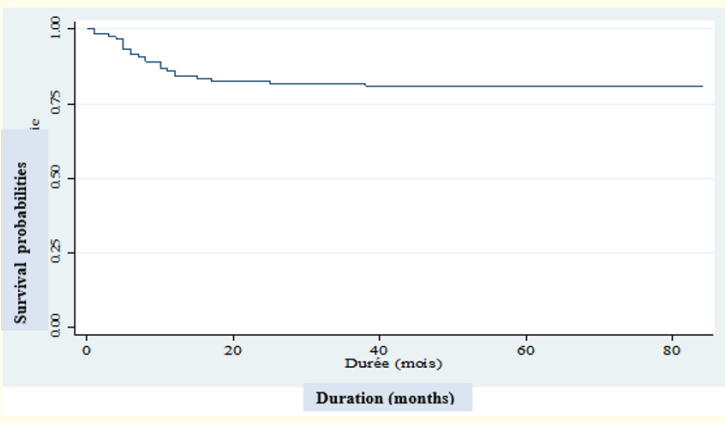

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier estimation of survival function of 121 HIV-exposed children included in the Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital cohort between 2010 and 2011.

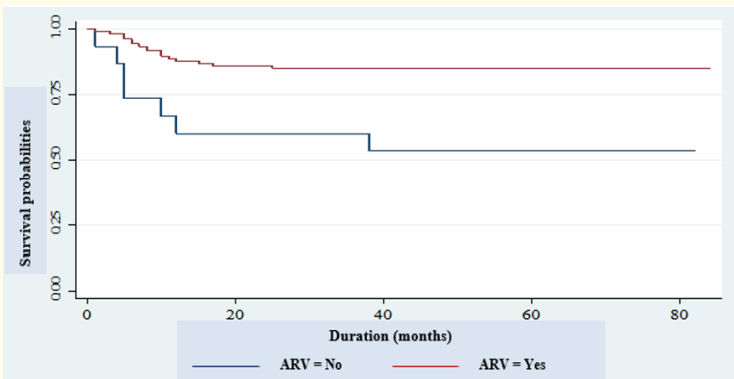

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier estimation of survival function of the 121 HIV-exposed children included in the Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital cohort between 2010 and 2011 depending on administration or not of ARV.

The children who have reached five years of age had a good clinical state in 93.8% (93/98) of cases. Moderate acute malnutrition was the only abnormality found out in 6.2% of cases. The two children screened and found HIV-positive were on antiretroviral therapy and had a good clinical state.

The main causes of death of all the exposed children were severe acute malnutrition (39.1%), pneumonia (23.7%), diarrhhea (13%) and severe malaria (8.6%). The death causes specific to the seven exposed children with negative PCR were mainly pneumonia (28.5%), diarrhea (14.2%) and severe malaria (14.8%).

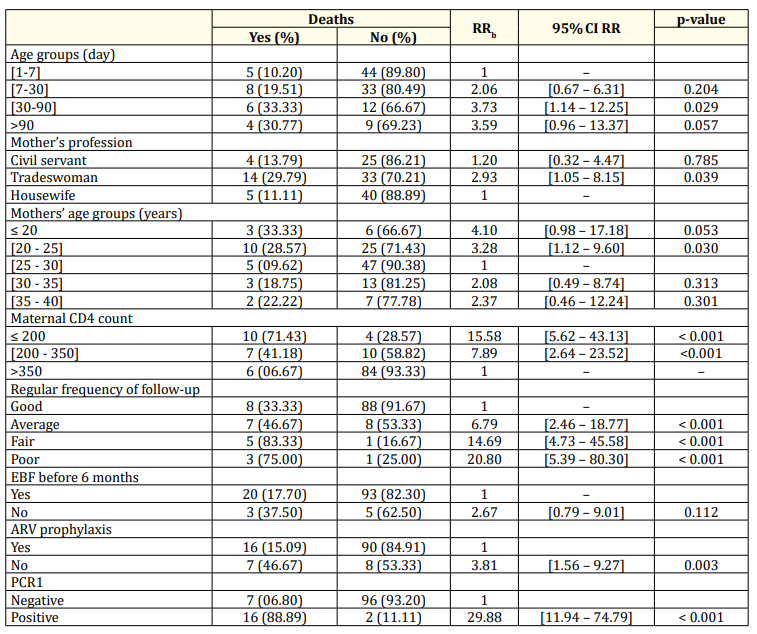

As regards associated factors, the univariate analysis (Table 1) showed that the main factors associated with the deaths of HIV-exposed children were: children’s age between 1 month and 3 months (p<0.029), mother’s age between 20 and 25 years (p<0.030), trade as mother’s profession (p<0.039), maternal CD4 count in the third quarter of pregnancy <350 (p<0.001), average, fair or poor followup (p<0.001), lack of ARV prophylaxis in children (p= 0.003) and positive PCR at 6 weeks of life (p<0.001).

Table 1: Univariate analysis of factors associated with deaths of HIV-exposed children followed-up in the Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital from 2010 to 2011. *EBF : exclusively breastfeeding.

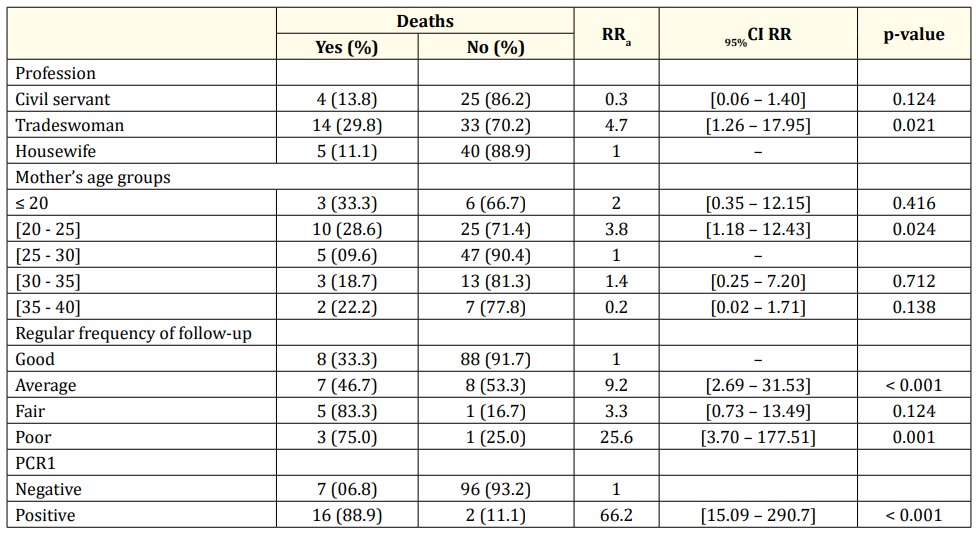

After the multivariate analysis (Table 2), four predictive factors for death had been identified: mother’s profession, mother’s age, regular follow-up and positive PCR: trading as mother’s profession exposing the child to 4.7 times more risk for death (p=0.021) than mother’s housewife status, mother’s age between 20 and 25 years exposing children to 3.8 times more risk of death (p=0.024) than mother’s age oscillating between 25 and 30 years; average and poor follow-up exposing respectively children to 9.2 times (p<0.001) and to 25.6 times (p=0.001) more to risk of death and positive PCR at 6 weeks exposing the child to 66.2 times more to risk of death (p<0.001).

Table 2: Multivariate analysis of factors associated with deaths of HIV-exposed children followed-up in the Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital from 2010 to 2011.

This work is a descriptive and analytical cohort monitoring study conducted in the pediatric unit of Borgou/Alibori Regional Teaching Hospital; it involved 121 HIV-exposed children. It enabled to describe their sociodemographic characteristics, the PMTCT specific responses provided to them, their virology status, and their serological status within 18 months and their future outcome after 5 years. As the objective is to investigate the survival of those HIVexposed children, it was therefore logical and reasonable to choose Kaplan-Meier method concerning survival probabilities and Cox model to identify the predictive factors for death. The study was carried out in accordance with a non-probabilistic method using a completeness technique; this may reduce possible biases in the selection of medical records. However, this study was carried out in a hospital and within the only site providing care to HIV-exposed children in the district of Parakou. Therefore, the findings of this study could not be extrapolated to a national health situation. Notwithstanding, the completeness technique chosen, the statistical tests used as well as the ethical measures taken enable us to argue that this study’s results are valid and that this research work complies with required ethical standards.

The mean age for children on inclusion was 35 days ± 6 days i.e. after one month of life. This age is above the WHO standards which recommend that child follow-up be initiated at birth [7]. In our context, this may be due to the fact that systematic examination of newborn at birth is not institutionalized. The sex ratio for children was 1.58 on inclusion. This male predominance has been reported in the literature [8,9]. During this study, mean maternal age was 27.5 years ± 4.7 years. A similar trend has been observed by many authors [8-10]. The predominant age group was the one from 25 to 30 years (43%). This age group corresponds to the young segment of the population which is sexually active. Mothers exerting trade as profession were predominant (29.8%). Saizonou., et al. made the same remark in Cotonou [10].

Protected breastfeeding has been practiced by 93.4% of mothers. A lower rate had been reported in Cotonou [10]. In our sociocultural context, breastfeeding is the natural method used for newborn and infant feeding. Although this practice is highly adopted in this study, weaning ages were variable; 51.2% of children were weaned between six and twelve months and 42.1% weaned before 6 months of age. A study carried out in the same medical unit in 2010 [9] had found out an association between duration of breastfeeding and infection risk. In this study, infection risk was particularly high when breastfeeding was practiced for more than six months. Besides, the national PMTCT guidelines applicable in Benin at the time of child inclusion recommended early weaning at 4 months of life [11]. This justifies the practice of early child weaning in the hospital unit during the follow-up. But from 2010, the WHO recommendations on exposed infant feeding have changed and the duration of protected exclusive breastfeeding has been prolonged to six months followed by diversification and cessation of breastfeeding when a nutritionally safe and appropriate diet without breast milk could be administered to the child [12]. This also explains that more than half the children included in this study have been weaned between 6 and 12 months.

As regards antiretroviral prophylaxis, it was administered to 87.6% of children. Similar results had been reported by Ahoua., et al. in Uganda [13]. In Burkina Faso, Ouedraogo Yugbare., et al. had observed in their cohort that 90.4% of children had received antiretroviral prophylaxis [14]. Those differences may be due to the fact that all newborns are not systematically attended in medical consultation at birth as illustrated by the required time limit for the first follow-up consultation in this study. They may also be due to the poor coverage estimated at 48% on the PMTCT site in the District at the time of inclusion of the children in the cohort [15].

As far as biological features are concerned, PCR at six weeks of life had been performed in all children with 14.8% as positive. Lower positive status rates of 0.46% and 1% had been observed respectively in Togo and in South Africa [16,17]. Positive PCR at six weeks of life reflects child early infection i.e. in utero or during delivery. The high level of infection noted in this study may be due to the PMTCT poor coverage on-site and to delay in screening pregnant women because of delayed first contact with maternities. Concerning HIV serology, positive status rate was 3%. 5.6% of HIVpositive status had been found out in the same unit in 2016 [18]. These results suggest that HIV-positive status rate is still high and requires that more effective responses be conducted upstream, especially in the maternities and within the community in order to reduce infection risk.

Among the 121 exposed children of the cohort, 98 (81%) had reached at least their fifth birthday of life. Survival probability at 18 months was 0.8264. A similar trend has been observed in the series of Becquet., et al. in Ivory Coast and Brahmbhatt., et al. in Uganda [19,20]. In this work, survival probability at 60 months was 0.8099. It was highly correlated to the existence of early HIV infection since positive PCR increased 66.2 times risk of death. The first eighteen months of life were the period during which children were the most vulnerable with 91.4% of deaths recorded.

The main causes of child deaths were severe acute malnutrition (39.1%), pneumonia (23.7%), diarrhea (13%) and severe malaria (8.6%). Among the dead children, HIV-infected children were predominant (69.5%). Those causes observed in our cohort are described as the main causes of childhood morbidity and mortality in the context of HIV [7,21,22]. 30.5% of the dead children had negative PCR and only one of them had negative serology at 18 months of life. It could be said with certainty that this only child was HIV-exposed but uninfected. The other children died before 18 months of age and their serological status was not known. One could not definitely conclude about their infection or non-infection. Referring to PCR at six weeks of life, one could envisage the possibility that those children are uninfected HIV-exposed children even though infection through breast milk after six weeks of life cannot be expressly ruled out. The causes of death specific to those children were pneumonia (28.5%), diarrhea (14.2%), and severe malaria (14.8%). Pneumonia is one of the current infections of uninfected HIV-exposed children. Many studies have described that, in those children, pneumonia may be caused by an unusually wide range of microorganisms, particularly Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cytomegalovirus and other viruses that cannot be treated by standard first-line antimicrobial treatment regimens [1]. Diarrhea represented one of the causes of mortality of those children (14.2%). Most often, it is related to infant feeding practices. And many authors have observed a similar frequency of diarrhea episodes in children, whether HIV-exposed or not [1,23]. In this study, severe malaria was also a cause of death in 14.8% of cases. The infants born to HIV-infected women present with more malaria episodes than those born to uninfected women [7]. The reasons for mortality of uninfected HIV-exposed children are multifactorial i.e. associating mothers’ health status, infant feeding practices and immune vulnerability inherent in uninfected exposed children; therefore, this exposes them to a more increased risk of infection [24].

Among the factors associated with the death of exposed children, four predictive factors for death had been identified after multivariate analysis: maternal age between 20 and 25 years, trade as mother’s profession, irregular follow-up and positive PCR. Maternal age between 20 and 25 years was related to child survival (p= 0.03). Becquet., et al. [19] had made the same remark. Death risk was multiplied by 3.8 in children born to those mothers. This may be due to the lack of experience of those young mothers in the follow-up of their children. Mothers’ trade profession was also associated with death (p=0.039). Death risk was multiplied by 4.7 in exposed children born to tradeswomen. This may be due to the fact that those mothers gave priority to their trade at the expense of follow-up appointments. Becquet., et al. [19] had not found a significant relationship between mothers’ profession and child deaths. Positive PCR at six weeks of life was significantly associated with the death of exposed children (p<0.001). The same association has been reported in the literature [9,13,14,19,20]. Positive PCR exposed children to 66.2 times more risk for death. Early contamination of the child leads to a fast progression of the disease during the first two years of life with more increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections [7]. In our cohort, 14.8% of children had positive PCR at six weeks of life; this indicates early contamination and points out that it is necessary to improve early screening and care for pregnant women during pregnancy and childbirth. An association between irregular follow-up and child death has also been found out. Regular follow-up contributed to better survival of exposed children.

The survival probability of HIV-exposed children at 5 years of age was estimated at 0.8099. Approximately one out of five exposed children died before fifth birthday in life. Seven out of ten dead children were infected due to in utero or perinatal contamination. The main predictive factors for death were maternal age between 20 and 25 years, mother’s trade profession, irregular follow-up and positive PCR at six weeks of life. In order to ensure a better survival for HIV-exposed children, there is an urgent need to improve PMTCT quality through systematic HIV screening in all pregnant women, ARV administration and regular follow-up of infected women and their infants.

Copyright: © 2019 Agbeille Mohamed F., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.