M Sellouti*, A Radi, M Kmari and O Agadr

Department of Pediatrics, Mohammed V Military Teaching Hospital, Rabat, Morocco

*Corresponding Author: M Sellouti, Department of Pediatrics, Mohammed V Military Teaching Hospital, Rabat, Morocco.

Received: September 24, 2019; Published: October 23, 2019

Citation: M Sellouti., et al. “Schizencéphaly : A Case Report”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.11 (2019):53-54.

Schizencephaly is an uncommon congenital cerebral malformation that involves the cerebral mantle and consists of a cleft that extends through the entire cerebral hemisphere from the lateral ventricle to cerebral cortex. Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is known to be associated with some of the disorders of neuronal migration and organization, including gray matter heterotopias, and polymicrogyria. We report the case of newborn with schizencephaly and congenital CMV infection.

Keywords: Schizencephaly; CMV infection

Schizencephaly is a cleft lined with gray matter and connecting the subarachnoid spaces with the ventricular system. Schizencephaly results from injury involving the entire thickness of the developing hemisphere during cortical organization and can be either congenital or acquired [1]. Clinical presentation depends on the size and location of the lesion.

The role of genes in the control of human brain development is becoming increasingly evident [2]. In fact, schizencephaly has recently been associated with a germline mutation in the homeobox gene EMX2 in 70% of the examined patient [3,4]. However, among the pathogenic factors, cytomegalovirus (CMV) should also be considered because it is the predominant transmissible agent associated with some neuronal migrational disorder, such as lissencephaly, pachygyria, and polymirogyria [5,6]. We report a case of newborn patients who CMV infection is suggested to be a possible factor for schizencephaly.

A 15-day-old female child, admitted for refusing to breastfeed. Antenatal history was uneventful. Family history was not significant. Normal vaginal delivery was at home. She cried soon after birth and was small for gestational age weighing 2kg, length 43cm and head circumference 28cm. Central nervous system examination revealed, truncal hypotonia, spasticity of left upper and lower limbs with brisk deep tendon reflexes. The power in the left upper and lower limb was 4/5. Anterior fontanelle was normal. Sutures were widely normal. The ophthalmologic examination showed a microcornea, a perilimbic subconjunctival haemorrhage and a total bilateral cataract closing (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Leukocoria.

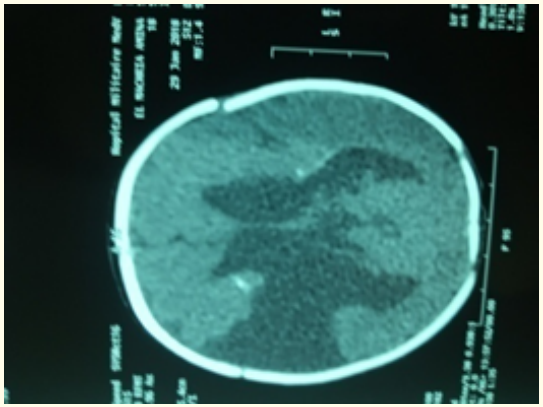

Biological assays showed hyperleukocytosis at 23500/mm3 (39% lymphocytes and neutrophils at 69%), hemoglobin at 16g/ dl, VGM at 85.2 μ3, MHC at 27 pg, MCHC at 33%, and a platelet count at 450.10³/mm3. C-reactive protein level was 12 mg/l. Ultrasonographic examination showed a dilatation of the lateral ventricles. A CT scan performed showed right small open-lip frontoparietal schizencephal with communication of the lateral ventricle associated to sub-cortical and periventricular calcifications (Figure 2). Virological investigations were positive for CMV DNA in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The infant was given Ganciclovir (CYMEVAN) at a dosage of 12 mg/kg one time daily for 6 weeks. After about 2 weeks of therapy, serum test for CMV DNA were negative. At the end of treatment, test for CMV DNA in the CSF and serum were negative.

Figure 2: Schizencephaly cleft in the right hemisphere.

Schizencephaly is a rare cortical malformation that manifests as a gray matter-lined cleft extending from the ependyma to the pia mater, with a wide spectrum of anatomical presentation, ranging from small, unilateral fused-lip clefts to large, bilateral open lip [7].

This malformation can present as an isolated disorder or may be associated with other brain abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, agenesis of the corpus callosum or septum pellucidum.

CMV is the most common cause of the congenital infection caused by the DNA virus belonging to the herpes virus group. The condition occurs by transplacental virus transmission. The target cells of CMV are the immature cells of the germinal matrix, resulting in widespread periventricular inflammation, tissue necrosis and subsequent predominantly periventricular calcifications. Besides involvement of the periventricular zones, which is seen in more than half of the cases, other sites of involvement include cerebral cortex and white matter, cerebellum, brain stem, and spinal cord. In early gestation, CMV infection can cause aberrations of the neuronal migration and organization. It has been reported that some of these occur as subtle cortical dysplasia which may be difficult to demonstrate by imaging modalities.

On the other hand, genetic studies seem to have a great relevance in the understanding of neuronal migrational disorder (NMD) [2], and schizencephaly has been associated with a germline mutation in the homeobox gene EMX2 in 70% of the examined patients [3,4]. In the remaining patients with schizencephaly not of genetic origin, including our reported case, the underlying damage could be supported by other conditions [7]. Among these, prenatal CMV infection may be suggested as a potential factor in the complex multifactorial pathogenesis of this NMD.

Clinical presentation depends on the size and location of the lesion. It can have varying effects on neurological development and overall development. Bilateral clefts are generally associated with quadriparesis and severe cognitive impairment [8]. MRI examination is definitive and is the imaging modality of choice. MRI identifies the anomalous grey matter along the cleft as well as the associated abnormalities such as heterotopias [9].

As a rule, therapeutic management of schizencephaly is conservative and predominantly consists of rehabilitation for motor deficits and mental retardation. These patients also need treatment for epilepsy. Surgical treatment is undertaken only in some cases with concomitant hydrocephaly or intracranial hypertension [10].

CMV infection causes multiorgan affection, but the most severe and permanent sequelae are those affecting central nervous system as a result of direct interference of the virus with neurogenesis.

Copyright: © 2019 M Sellouti., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.