Lara-Pérez Eduardo Antonio1*, Virgen-Ortega Cesar2, Josué Elí Villegas-Domínguez3 and Márquez-Celedonio Félix Guillermo4

1Medical Specialist in Pediatrics, Director of the Asthma Attention Clinic (CLINASMA), Titular Academic, Mexican Academy of Pediatrics C.A., Veracruz, Mexico

2Medical Specialist in Pediatrics, President of the Tabasco College of Pediatrics. CONAPEME, Mexico

3Master in Epidemiology, Full Time Professor in Medicine Faculty “Dr. Porfirio Sosa Zárate”, University of the Valley of Mexico, Veracruz Campus, Mexico

4Master in Clinical Investigation, Specialist in Family Medicine, Research Coordinator, Medicine Faculty “Dr. Porfirio Sosa Zárate”, University of the Valley Mexico, Veracruz, Mexico

*Corresponding Author: Lara-Pérez Eduardo Antonio, Medical Specialist in Pediatrics, Director of the Asthma Attention Clinic (CLINASMA), Titular Academic, Mexican Academy of Pediatrics C.A., Veracruz, Mexico.

Received: August 17, 2019; Published: September 23, 2019

Citation: Lara-Pérez Eduardo Antonio., et al. “Effect of Ionized Nasal Saline Solution of Neutral Ph in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Pulmonary Function of Asthmatic Schoolchildren”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.10 (2019):101-107.

Relevance: Asthma affects 10 to 37% of the world population; it concurs with rhinitis. The administration on asthmatic children of nasal ionized saline solution that improves inspiratory and expiratory flows and lowers the infections of upper respiratory tract would contribute to achieve therapeutic goals of the condition.

Objective: Determine the effect of the administration of nasal ionized saline solution on the nasal peak inspiratory flow, peak expiratory flow and frequency of respiratory infections on asthmatic children.

Design: Test – Retest intervention study with 4 months’ follow-up performed on asthmatic children in 2018. Analysis with ChiSquared, Mann-Whitney U, Student’s t and Friedman tests.

Setting: The trial was conducted in Asthma Attention Clinic CLINASMA and in the Medical School of the University of the Valley of Mexico, Veracruz, Mexico.

Participants: Patients with partially controlled or not controlled asthma, without previous diagnosis of rhinitis, male or female from

6 to 14 years old, residents of Veracruz, México, selected from the external consultation of the asthma clinic.

Intervention: Nasal administration of 2 shots on the nostrils, twice a day or on free-demand, of neutral pH electrolyzed solution of super oxidation that contains active species of chlorine and oxygen at 0.0015%. It was applied every day of the week for 4 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures: Nasal peak inspiratory flow, peak expiratory flow and upper respiratory tract infections. The hypothesis that the administration of neutral pH electrolyzed super oxidation solution improves the respiratory function and the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections of asthmatic children was previously stated.

Results: 80 children of 8.7 ± 2.1 years old, height of 131 (13) cm, 48 (60%) males. Basal nasal peak inspiratory flow was 58 (19) L/ seg and 105 (29) four months after (p < .001); basal peak expiratory flow 182 (56) and 222 (67) at the end of the follow-up (p < .001). The respiratory infections were 71 (89%) patients on the first month and 0 (0%) on the fourth (p < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance: The administration of nasal ionized saline solution in asthmatic children improves the nasal peak inspiratory flow and the peak expiratory flow and reduces the upper respiratory tract infections since the first month of administration.

Keywords: Asthma; Rhinitis; Peak Expiratory Flow; Respiratory System Infections

Question: What is the effect of the neutral pH ionized nasal saline solution on asthmatic schoolchildren’s upper tract infections and pulmonary function?

Findings: In this intervention study with administration of neutral pH ionized nasal saline solution for 4 months to 80 asthmatic children, NPIF was raised 79.3%, PEF 22.3% and the frequency of upper tract infections was reduced to cero on the last month of the follow-up.

Meaning: On asthmatic schoolchildren the administration of neutral pH ionized nasal saline solution improves the NPIF, PEF and lower the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections.

Rhinitis and asthma are frequent conditions worldwide, their prevalence reaches rates from 10 to 37.6% depending on the country, region, season, age, habitat and economic status [1-4]. Asthma is a disease that is characterized by chronic inflammation of the respiratory airway and that is clinically manifested for variable limitation of the expiratory flow in addition to the typical symptoms of wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness and cough. The limitation of the pulmonary expiratory function varies in magnitude and through time in healthy population and in the asthmatic patient from completely normal function to severe obstruction. The respiratory infections, especially viral infections, in addition to other factors can onset the presentation or exacerbation of the symptoms [5]. In addition to inflammation, bronchial spasm and mucus hypersecretion are physiopathology components of asthma. The excess of mucus not only blocks the respiratory airway, but also contributes to the hypersensitivity of the airway, and is a marker of poor control of the disease and is related with its mobility and mortality [6,7]. Also, the relation of comorbidity between rhinitis and asthma has been demonstrated, more precisely with poorly-controlled asthma [8], and with frequent upper respiratory tract infectious conditions [9]. This association of recurrent respiratory infection, atopic rhinitis and oral breathing impacts on a poor control of the asthma in all age groups [10-13].

The evaluation of the asthmatic patient must include the assessment of the frequency and severity of the symptoms and signs of the disease, its clinical course and the risk of presenting complications or adverse results [1,14]. The pulmonary function follow-up is necessary to optimize the management and achieve the therapeutic goals; the control degree of the patient is stablished through the measurement of the forced expiratory volume in the 1st second (FEV) or the maximum expiratory flow (PEF); PEF is also useful to obtain a basal measurement of the management plans or to, through its monitoring, evaluate the treatment response and predict the symptom worsening risk. PEF is widely used in the management of the asthmatic patients, and its daily measurement contributes to the better control of the upper airway obstruction [15,16], it can be complemented by evaluating its relationship with the nasal peak inspiratory flow (NPIF) [17,18].

The goals of the management of the asthmatic patient are oriented into reaching an adequate control of the symptoms, lower the exacerbation risk, preserve the pulmonary function, lower the possibility of the fixed obstruction of the airflow and of the secondary effects of the drugs [1]. The treatment includes maintaining pharmacologic options as short and long action β2-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonist, anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies; and rescue drugs to the treatment of the disease exacerbation [1,19-21]. Non-pharmacologic options that include the nasal irrigation with isotonic or hypertonic saline solution have shown efficacy and safety in children with nasal congestion caused by infections, allergic diseases, and rhinosinusitis, and they can reduce the use of antihistamines, corticosteroids, and antibiotics during upper respiratory tract infections [22,23]. The neutral pH electrolyzed solution of super oxidation has shown on cell cultures with the highest concentrations decrease of up to 96% of the infectivity of influenza virus [24], and on studies with murine bone marrow mastocytes it’s linked with cell membrane stabilization by inhibiting the Ig-E antigen-induced degranulation and the release of cytokines [25]. An acid electrolyzed solution has been tested to be administered by nasal irrigation after a paranasal sinuses functional endoscopic surgery without showing any difference on the results with the patients that received normal saline solution [26]. The comprehension and management of the nasal breathing on the asthmatic, especially in the ones that also present rhinitis, could represent benefits on the clinical course of the disease and on the patient’s life quality; therefore, the present trial has the objective of evaluating the clinical efficacy of a neutral pH electrolyzed superoxidative solution on the pulmonary function quantified by PEF, NPIF, and the frequency of respiratory infections on asthmatic children with bad control of the disease.

A longitudinal, prospective and comparative interventional trial was made with test-retest measurements in children and adolescents of both genders with at least one year with the diagnosis of bad-controlled asthma and with pharmacological management, without previous identification of rhinitis and with intercurrent episodes of upper respiratory tract infections. The diagnosis of asthma was made following the 2017 actualization of the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) [1], specially on patients who presented breathing difficulty, wheezing, chest tightness and cough, typical symptoms of asthma, and in those in whom expiratory flow limitation was confirmed with PEF. A differential diagnosis with other pulmonary conditions such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, congenital heart disease, presence of foreign bodies on the upper airways and primary ciliary dyskinesia. The bad-controlled status was identified by the presence in the four previous weeks of at least 3 of the 4 following symptoms: diurnal symptoms of asthma more than twice a week, awakenings during the nights caused by the disease, need of medication for the symptoms more than twice a week and physical activity limitation. The study was made from October 2017 to May 2018 previous informed consent signed by the parents or by the responsible of the participants and authorization of the University of the Valley of Mexico Veracruz Campus research and bioethics committee.

A clinical evaluation was made in the beginning and repeated every month for 4 months by the same investigator from 11:00 to 19:00 to every patient who was included in the trial to confirm the diagnosis, the degree of control of the asthma, clinical course, presence of infections and feverish episodes of respiratory origin > 38°C and pulmonary function with nasal peak inspiratory flow (NPIF) and peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurements; the fulfillment of the selection criteria was also confirmed. The initial evaluation included the recollection of sociodemographic data, age, sex, and anthropometric measurements done with Detecto® weighing machine and stadiometer; the NPIF was measured with a flowmeter using liter per minute scale with a nasofacial mask (MD Instruments®) and the PEF was measured with a Truzone® flowmeter in liter per minute scale, requiring to had have at least 30 minutes of rest after having realized physical activity or after having drunk hot or stimulant beverages. The measurement of the peak inspiratory and expiratory flows was made before starting the therapeutic intervention and every month for 4 months, with the patient standing. In each occasion, 5 tries were made for each flow and the higher grade was used as the one to register. Personal values of each flow and their difference, and the PEF comparison between the values for healthy children who live at sea level by gender and age, were used [27].

After the initial evaluation, all the patients were instructed to administer by nasal route an electrolyzed super oxidation solution with neutral pH and active species of chlorine and oxygen at 0.0015% that has a wide-spectrum antimicrobial action, including fungus and viruses. A vertical position administration in each nostril, twice a day, was indicated, but with the instruction to use it as required based on the nasal hypersecretion. The application was made every day of the week for 4 months.

A statistical analysis with data description using absolute and relative frequency, N (%), central tendency measurements and dispersion, media (SD) or median (range) was made. The inferential analysis was made using Chi Squared test with Yates correction, Mann-Whitney U test, Student’s t test and Friedman test with a significance level of 0.05 to reject the null hypothesis. The analysis procedures were done with the 25th version of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software.

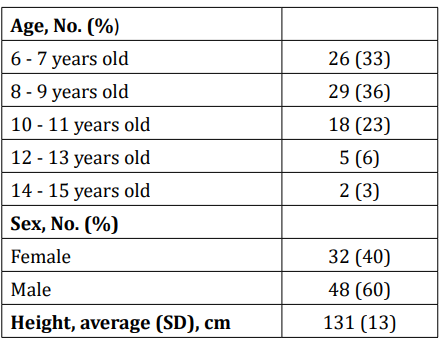

Eighty patients aged 9 (2) years were included on the trial, 62 (78%) had from 8 to 10 years and 18 (23%) 11 to 15 years; height of 131 (13) cm, 48 (60%) were male and 32 (40%) female (Table 1). 64 (80%) presented upper respiratory tract infection during the month of the initial measurement, 51 (64%) were acute infections and 13 (16%) were chronic. On the basal measurement of the studied sample PEF value was 189 (56) L/sec which represented 66% of the expected according to the normal reference value at sea level for the age groups included on the intervention. In males, PEF was 184 (53), 66% of the expected, and in females it was 178 (59), 67% of the reference healthy patients. On the other hand, initial NPIF in the total of the sample was 58 (19) L/sec.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the studied asthmatic patients N= 80.

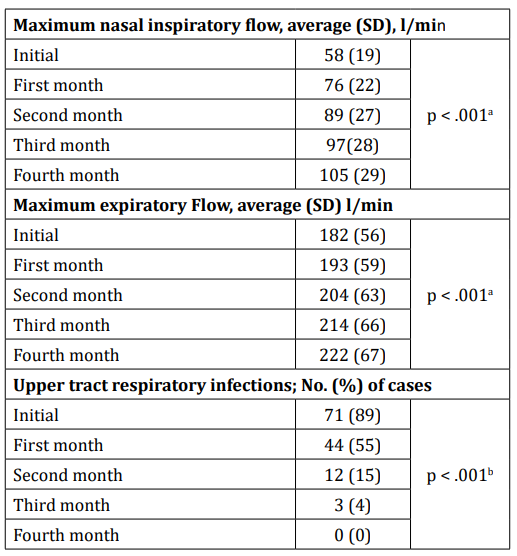

On the general evaluation, without considering patient’s gender, NPIF went from 58 (19) L/sec on the basal measurement to 76 (22) L/sec after a month from the beginning from the trial and 105 (29) L/sec at the end of the four months of the intervention with a total increase of 79% (p < .001). PEF went from 182 (56) L/sec on the initial measurement to 193 (59) L/sec with a month of intervention and 222 (67) L/sec at the end of the four months of treatment which represented 80% of the average expected value at sea level for the studied population (p <. 001). On the PEF basal measurement, 45 (56%) of the patients were in the range of 50 to 69% of the normal reference value of the sample at sea level, which after four months of intervention 63 (79%) were on the 70 to 89% interval of the reference value and 12 (15%) obtained a value higher than 90% of the PEF reference. The number of patients who presented acute or chronic respiratory infections went from 64 (80%) during the initial month of evaluation to 0 (0%) at the end of the follow-up period (p < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2: Evolution of NPIF, PEF and respiratory infections in children managed with ionized solutions N = 80.

a p value obtained with Friedman’s test for repeated measures.

b p value obtained with Chi squared test with Yates correction

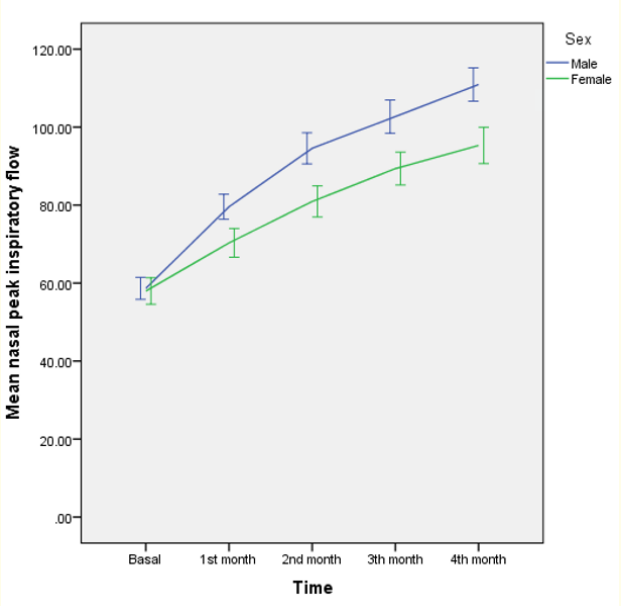

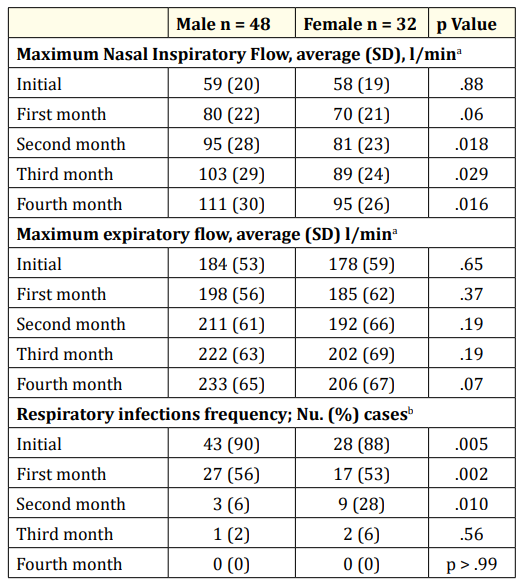

In the results by gender, male patients showed 59 (20) L/sec of NPIF on the basal measurement and 111 (30) L/sec at the end of the intervention with an increase of 89% (p <. 001), meanwhile on female patients the measurement was 58 (19) at the beginning and 95 (26) after four months of treatment with a 64% increase (p < .001), however, the differences between genders when comparing NPIF results were statistically significative from the second to the fourth month (p < .05). PEF in males went from 184 (53) L/sec on the basal measurement which represented 66% of the expected value for the sample to 233 (66) L/sec at the end of the intervention, which corresponded to 82% of the expected value for the studied population (p < .001), while in females it was of 178 (59) L/sec at the beginning, 67% of the expected value for the sample at sea level and 206 (67) at the end of the four months of treatment, 76% of the average for healthy patient of the same age, gender and at sea level (p < .001); PEF comparison between sex categories didn’t show statistically significant differences at any time (p > .05) (Figure 1,2) During the basal measurement 43 (90%) of the male patients presented upper respiratory tract infections which reduced to 1 (2%) on the third month of treatment and to 0 (0%) on the fourth month of intervention (p < .001). Meanwhile, on female patients it went from 28 (88%) ill patients on the basal measurement to 2 (6%) after three months and to 0 (0%) on the last month of intervention (p < .001),

Figure 1: Evolution by sex of the Peak Expiratory Flow with the nasal administration of a neutral pH electrolyzed solution.

Figure 2: Evolution by sex of the Nasal Peak Inspiratory Flow with the administration of neutral pH electrolyzed saline solution.

Table 3: Evolution of the NPIF, PEF and respiratory infections in children managed with ionized solutions classified by sex N = 80.

a p value obtained with Mann-Whitney’s U test.

b p value obtained with Chi squeared with Yates correction test or Fisher’s exact test

On the patients with history of acute respiratory infections at the beginning of the trial, NPIF went from 55 (15) to 97 (26) L/ sec at the end of the intervention, 76% increase (p < .001) and on children with chronic respiratory infections from 60 (23) to 110 (35) L/sec respectively, 84% increase (p < .001). Patients without history of respiratory infections, MNIF went from 67 (25) and 124 (27) at the end, with an 84% increase (p < .001); differences between the three comparison groups were statistically significant (p = .005) On the group of patients with history of acute respiratory infections the results of the PEF measurement were 170 (48) L/ sec, 68% of the expected value in comparison with normal individual on the basal measurement and 205 (57) L/sec, 76% of the normal value at the end of the four months of the trial (p < .001) while on the group with chronic infections PEF went from 178 ± 58 L/sec, 66% of the normal reference value on the initial measurement and 227 (74) L/sec, 82% of the reference value (p < .001); the group without respiratory infections showed a basal PEF of 222 (62) L/sec, 61% of the reference value and 273 (68) L/sec at the fourth month of intervention. When comparing the three groups, the differences were statistically significant on the initial (p = .016) and final (p = .004) evaluation.

The findings in our study of the effects of a neutral pH superoxidative electrolyzed solution on the pulmonary function and the frequency of respiratory infections in children and adolescents with asthma or allergic rhinitis showed a significant improvement on the NPIF and PEF measures, so did the lowered number of respiratory infections on the patients. NPIF showed a 79% increase after four months of treatment with the electrolyzed solution compared to the initial measure, whereas PEF increase was 22.3%, this last indicator meant that after four months after the intervention, almost 80% of the patients were on the 70 to 89% range of the expected PEF value for the altitude in which the studied population was. The important improvement of the NPIF has clinical transcendence representing a significative decrease on the nasal segment airway obstruction and that it can contribute given its showed correlation with PEF [28] in the improvement of pulmonary function on an asthmatic patient.

Our findings also showed that the children and adolescents submitted to the intervention with the neutral pH super oxidation electrolyzed solution significantly decreased the frequency of respiratory infections from 80% in the month in which the baseline measurement was performed to none in the fourth month of follow-up. This significant reduction on the number of respiratory infections can be caused by the effect of the intervention on the mucus hypersecretion, which constitutes a characteristic of the allergic rhinitis and the bronchial asthma and contributes to its mortality [6]. or it could be caused by its bactericide properties and the reduction of the viral multiplication demonstrated by the electrolyzed solution on cell cultures [24]. Asthma, rhinitis and respiratory infections present a seasonal variation demonstrated in many studies [29] therefore when interpreting our results, it should be considered that the patients on this trial were submitted to the experimental intervention during the months that correspond to the autumn and winter season on the north hemisphere, period which is associated with a higher number of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis and respiratory infections episodes on the south region of Mexico [4,30]. and even after, the benefic effect of the neutral pH electrolyzed solution was maintained.

The benefic effects shown by the experimental intervention on the NPIF, PEF and frequency of respiratory infections were constant and progressives since the start of the treatment and until the fourth month when the follow-up was concluded; clinical course showed no significant differences between male and female patients and with history of acute or chronic upper tract respiratory infections. The results of our study are relevant and have the strength of proceed from an applied therapeutic intervention and prospectively evaluated, however, it has the inherent weaknesses of the open experimental studies without blinding and the testretest design in which the lack of a control group that allows to compare the results of the therapeutic proposal. Future controlled clinical essays could include comparison groups with saline solution that has shown to have benefic effects as an adjuvant in some studies with asthmatic patients [23].

In comparison with the saline solution, Hermelingmeier KE., et al. [23] identified through a systematic review and metanalysis 50 relevant essays published on the period from 1994 to 2010 of which 10 fulfilled their inclusion criteria. This review showed that on interventions of approximately 7 weeks, the nasal irrigations of nasal saline solution on allergic rhinitis reduced 27.7% the nasal symptoms, 61.1% the medicine consumption and that improved the life quality 27.9%; however, in the literature review we didn’t fine clinical studies that explored the effect of the electrolyzed solution on the manifestations or clinical course of the asthmatic patient with allergic rhinitis.

From a clinical point of view, our findings considered the coexistence of asthma and allergic rhinitis and added the improvement of the nasal function as a component of the child or adolescent asthmatic patient using a neutral pH super oxidative electrolyzed solution, intervention that can be constituted as an adjuvant measure of the treatment. The management proposal stablished on the experimental intervention of this study allows us to attend the nasal and bronchial segments that are affected by the disease and to stablish its assessment in accordance with previous studies [18,28]. The obtained findings support that the studied therapeutic intervention can improve the clinical course and the life quality of the patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis stablishing improvement on the pulmonary function and decrease of the frequency of respiratory infections showed on our study, but also by its known bactericidal effects and over the viral multiplication, as on the reduction of the nasal an bronchial hypersecretion.

In conclusion, the administration via nasal irrigation of neutral pH super oxidative electrolyzed solution has a benefic effect on asthmatic children with allergic rhinitis since it contributes in the recovery of NPIF and pEF and reduces the frequency of infectious respiratory tract episodes, regardless sex or acute or chronic infec-

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest, including financial interests, industrial relations or affiliations and have not received financing that would represent a conflict of interest.

Copyright: © 2019 Lara-Pérez Eduardo Antonio., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.