Lindsay A Taliaferro1*, Joanna Mishtal2, Veenod L Chulani3, Meagan Acevedo MS4, Tiernan C Middleton BS5 and Marla E Eisenberg ScD MPH6

1Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Central Florida, USA

2Department of Anthropology, University of Central Florida, USA 3Adolescent Medicine Program, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, USA

4College of Medicine, University of Central Florida, USA

5College of Medicine, University of Central Florida, USA

6Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, University of Minnesota, USA

*Corresponding Author: Lindsay Taliaferro, Department of Population Health Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Central Florida, Orlando, USA.

Received: August 29, 2019; Published: September 10, 2019

Citation: Lindsay A Taliaferro., et al. “Communicating Effectively with Sexual Minority Youth: Perspectives of Young People and Healthcare Providers”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.10 (2019):32-39.

We sought to explore perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) youth, as well as pediatric and family medicine residents and physicians in-practice, about their experiences, preferences, and context of discussions regarding sexual orientation during clinical encounters. We conducted qualitative, semi-structured interviews with 22 LGBQ young people aged 18 - 24 and 24 pediatric/family medicine residents/physicians in-practice. Data were analyzed using a Grounded Theory approach. We first analyzed in-sample data, and then triangulated findings from both samples to search for convergences and divergences in perspectives. Two primary themes and three sub-themes emerged. One primary theme involved disclosure of patients’ sexual orientation. Another was barriers and facilitators of effective communication, within which we identified three sub-themes – patients’ fears of judgment, presence of parents, and verbal and non-verbal language. Overall, findings showed several commonalities and differences in patients’ and providers’ perspectives regarding facilitators and barriers to communication. Findings included discrepancy between patients’ consistent desire for providers to broach the topic of sexual orientation, and mixed perspectives held by providers about who should initiate this conversation and when he/she should do so. Knowledge of patients’ sexual orientation is important for providing patient-centered care that includes appropriate anticipatory guidance and health education. Providers may need additional training focused on communicating effectively with young LGBQ patients, including how to initiate conversations about sexual orientation and respond without judgment. Non - judgmental responses involve verbal and non-verbal body language that helps ensure patients feel comfortable, safe, and accepted.

Keywords: Sexual Minority; Qualitative; Interview; Communication

LGBQ: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Or Queer; IDI: In-Depth Interview

Youth who identify as a sexual minority (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer; LGBQ) represent a vulnerable subpopulation experiencing significant health disparities, compared to heterosexual youth, such as greater depression, self-injury, suicidality, eating disorders, high-risk sexual behavior, pregnancy, STIs, substance use, and homelessness [1,2]. Further, sexual minority youth demonstrate disparities in accessing quality healthcare services offered by culturally competent providers. Research indicates a continued gap in care for sexual minorities that has resulted in persistent health disparities among this population, including those associated with the leading causes of death for adolescents [3,4].

Pervasive explicit and implicit bias against sexual minorities by healthcare providers may contribute to inequities in quality healthcare and health disparities among LGBQ youth [5,6]. LGBQ young people often remain invisible to the healthcare system, lacking access to knowledgeable, culturally competent healthcare providers [4,7]. Many physicians feel unprepared to adequately address issues related to sexual orientation among youth [8].

Several professional medical associations recommend providers discuss sexuality with all adolescents, and provide non - judgmental communication about sexual orientation [7,9-13]. However, less than 40% of physicians report completing a sexual history with adolescent patients [14], and less than half of medical students report regularly screening for same-sex sexual activity [15]. When discussions about sexuality occur, they usually remain brief [16]. Yet, youth report more positive perceptions of healthcare providers and take more active roles in their healthcare when clinicians facilitate conversations about sensitive topics [17]. Disclosure of sexual orientation to healthcare providers results in increased comfort and satisfaction, better communication, and a greater likelihood of seeking necessary health services among adult sexual minority patients [18].

One gap in the literature on communication between LGBQ patients and healthcare providers includes limited research regarding the perspectives of young LGBQ patients, as well as pediatric and family medicine physicians who work with youth. In addition, in-depth data regarding the experiences and preferences of LGBQ patients and physicians is lacking due to limited use of qualitative research methods. We sought to address these gaps to enhance providers’ understanding of the needs of LGBQ patients and discrepancies in perspectives by conducting in-depth individual interviews with LGBQ youth (aged 18 - 24) and pediatric and family medicine residents and physicians in-practice, with the aim of understanding and comparing the experiences, preferences, and context of patient-provider discussions regarding sexual orientation during clinical encounters.

We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDIs) between July 2017 and March 2018 with two samples: (1) youth aged 18 - 24 who self-identified as LGBQ; and (2) pediatric or family medicine residents, or practicing pediatricians or family medicine physicians whose patient populations include adolescents/ young adults. We excluded youth if they identified as transgender because the healthcare needs of this population are often unique compared to LGBQ patients (e.g., need for transition - related services) [19,20], and physicians who were not in pediatrics or family medicine because providers in these specialties care for the vast majority of youth (aged 10 to 24). Participants were recruited using purposeful and snowball sampling [21]. The LGBQ youth were recruited by distributing the study recruitment flyer to local universities through, for example, Diversity Offices, Pride Coalitions, LGBT + Services, and Pride Commons; LGBT - specific community service organizations and healthcare clinics; and pediatric and family medicine physicians known to the study team; as well as through snowball sampling used with other youth LGBQ participants. We recruited the physician sample through the Academic Pediatric Association’s Continuity Research Network (CORNET), referrals from residency directors known to the study team, and snowball sampling with other physician participants. Participants were emailed the informed consent form, had an opportunity to ask interviewers any questions, and provided verbal consent prior to commencing the interview. The University of Central Florida Institutional Review Board approved the study.

We developed the 24 - item IDI guides for patients and providers through a review of the research literature and consultation with members of the study team with expertise in the health of sexual minority youth. We pre-tested the questions with eight physicians (2 pediatricians, 1 family medicine physician, 2 pediatric residents, and 3 family medicine residents) and four LGBQ young people to ensure phrasing was culturally appropriate and well - worded [21], and revised questions based on pre - test feedback. The IDI guide topics for youth included perceptions of physician awareness and capabilities of working with LGBQ patients; sources of perceived biases and stigma; perceived quality of care; barriers to disclosing sexual orientation and related issues, including changes in perspective from earlier adolescence; and thoughts on improving quality of care for LGBQ individuals. The provider guide included questions regarding physician perceptions of their knowledge, readiness, and ability to work with LGBQ adolescent patients; anti - LGBQ biases (implicit and explicit); physician training and awareness of LGBQ healthcare issues; and needs and desires regarding LGBQ - related training.

Interviews were conducted by two medical students trained in qualitative research methods. One student conducted all LGBQ youth interviews, and the other conducted all physician interviews. All interviews occurred via telephone. Participants provided verbal consent and agreed to be audio - recorded. Interviews lasted 20 - 40 minutes. Participants received a $35 electronic gift card for their time.

Recorded interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim. We generated and refined codebooks through an iterative process. To establish consistency, two members of the study team individually coded a transcript from each sample and met to resolve minor thematic differences to generate preliminary codebooks. Further coding and analysis yielded additional themes and sub - themes for each codebook. All transcripts were coded by two members of the study team. Completion of the coding process generated a detailed thematic dataset for each sample, which were analyzed using NVivo 11 software and a Grounded Theory approach [22]. We first analyzed in - sample data separately, and then triangulated findings from both samples, which allowed us to search for convergences and divergences in perspectives [23] within two thematic domains: (a) disclosure of patients’ sexual orientation, and (b) communication barriers/facilitators.

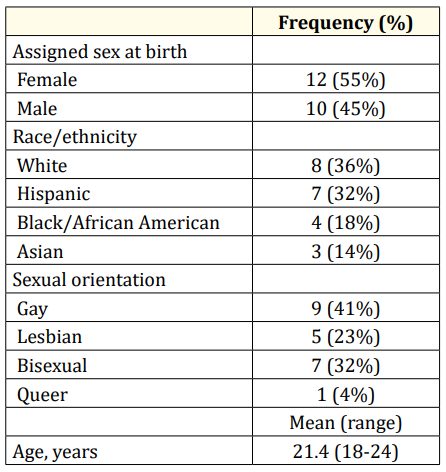

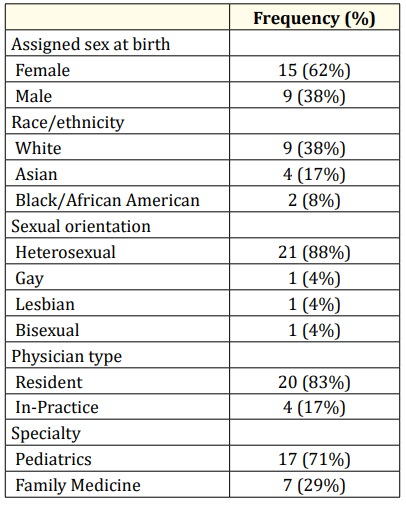

The youth sample included 22 participants, and the physician sample included 24 participants. Participant characteristics appear in tables 1 and 2. The respective samples permitted saturation of themes in each sample [22,4].

Table 1: Youth Patient Sample Demographic Characteristics (N = 22).

Two primary themes and three sub - themes emerged across the samples. One primary theme involved disclosure of patients’ sexual orientation. Another was barriers and facilitators of effective communication, within which we identified three sub-themes – patients’ fears of judgment, presence of parents, and verbal and non-verbal language.

We found discrepancies between LGBQ youths’ and physicians’ perspectives regarding needing to know patients’ sexual orientation as well as the process by which this information was disclosed.

Table 2: Resident and Physician In-Practice Sample Demographic Characteristics (N = 24).

All LGBQ youth felt it was important for healthcare providers to know patients’ sexual orientation, primarily because they felt clinicians should address LGBQ - specific healthcare issues when working with a patient who identifies as a sexual minority.

“Oh yeah, definitely. Because they could ask the right questions and check they’re doing the right things.” –Lesbian female (YA14)

“I feel like most health issues that are focused on aren’t dealing with (…) LGB issues. It’s mostly for people that don’t identify as that.” – Bisexual female (YA10)

Others described the importance of this information in understanding patients’ potential health problems. For example, when asked if knowing patients’ sexual orientation is helpful for a healthcare provider, participants explained:

“Definitely yes. (…) [W] hen you look at statistics on everything from HIV transmission to – even rates of sexual assault for bisexual women are really high. If a provider knew that, they may be able to have a better idea of what could be going on.” – Queer female (YA16)

“Yes. (…) [T] here’s probably things that are dangers to your health that tie into your sexual orientation that I’m not aware of. So it’s probably good for them to have it in the back of their mind, just like they know everything else about you.” –Gay male (YA17).

Another important reason respondents shared involved clinicians’ ability to offer appropriate anticipatory guidance and health education to LGBQ patients.

“Absolutely. There are so many things that a lot of LGBT people may not know about, especially when practicing safe sex, just because they may not feel comfortable divulging that information. But I think it’s definitely something that can be very beneficial to both the physician and the patient.” – Bisexual female (YA21)

“Just because I think they’ll have a better idea of how to treat you and give you health prevention tools and resources.” –Bisexual male (YA2).

However, though all LGBQ youth thought knowing patients’ sexual orientation was important, many indicated a clinician never asked them about their sexual identity, thus, they initiated the discussion or never disclosed this information.

“But I felt like she kind of assumed that I was with guys, and I should do this or this. But after I told her, ‘Yeah, I’m sexually with a woman’ – I just feel like maybe she could have been more informed with that. It’s really hard to explain.” – Lesbian female (YA5).

Healthcare providers offered mixed perspectives regarding discussing sexual orientation, when asked whether the topic should be initiated by the patient or provider. Many believed providers should inquire about sexual orientation.

“I think it should be initiated by the provider, because like I said, I think that a lot of teenagers have a hard time just bringing this up out of the blue, but if they're prompted, I think many more are willing to talk about it.” –Pediatric resident (MD11).

“I now try and ask at every appointment, for every one of my adolescent patients (…). I think it’s a topic that no one talks about. Or not no one, but we just aren’t trained to talk about. But you can achieve a really healthy conversation when it’s initiated. I don’t think the patient should have to start it.” – Family medicine resident (MD4).

Other providers were either ambivalent about who should bring-up sexual orientation or thought patients should initiate this disclosure.

“I think it should be initiated by the patient, but I think it usually isn’t, [laugh] and so we have to initiate it. But I think ideally it would be great if the patients just wanted to discuss and asked the questions that they had, without us having to prod them. [laugh]” –Pediatrician (MD21).

“It depends on the rapport with the patient (…). But I definitely think if the patients are concerned enough about it, they should bring it up.” –Pediatric resident (MD10).

“I guess I would say by the patient? (…) Because it could easily be seen as threatening or condescending if the provider even brings it up, right? –Family medicine physician (MD24).

Still, some providers thought discussing sexual orientation was relevant during routine physical or well visits, but not during acute visits. For example, a pediatric resident thought knowing one’s sexual orientation was “not as pertinent, or not pertinent to sexual practices” during “emergency room” or “acute visits.” Finally, a few did not believe knowing patients’ sexual orientation was important in providing healthcare in general.

“Everybody’s a male or a female. It doesn't matter what their sexual preference is (…) that’s how physiology is oriented, is male and female. But it doesn’t matter comfort on treating somebody versus sexual orientation, because everybody gets treated with the same general guidelines of compassionate healthcare. (…). I feel that there is an overemphasis on the LGBT community. I don’t feel that they are any different than the rest of the community.” –Family medicine resident (MD3).

Most of the LGBQ youth felt much more comfortable during healthcare visits in young adulthood than adolescence because they now felt less ashamed of themselves and less fearful of others’ judgment. However, worry about judgment by clinicians still concerned these youth. Therefore, the vulnerability to potential judgment also shapes effective communication.

“So I feel like there’s kind of a sense of judgment, but it’s not explicitly said. But I feel like there’s kind of a shift in the conversation. And two, it’s because I don’t know if they would react well or are OK with that or not, or if they would know how to go about addressing that.” –Gay male (YA9)

“I also think that everybody has a right to feel comfortable with their doctor, and I don’t feel a doctor should judge me, because it’s not really their place. It’s a confidential area. So I think it is important for the health system to be open to everybody, despite what they believe.” –Lesbian female (YA5).

Physicians acknowledged that LGBQ youth probably feel fearful about being judged during healthcare visits. In general, they believed that expressing a non-judgmental position was important and one way to improve communication with LGBQ patients.

“I think it’s still somewhat of a taboo subject, that there’s a stigma against this community, and that they don’t feel like necessarily every provider will advocate for them or help them with their unique needs. (…) I am able to have a non-judgmental ear.” –Pediatric resident (MD19).

“I would say part of it is limited knowledge of how to treat adolescents in that setting. (,,,) [W]e were taught in medical school that you're non-judgmental, and you try and provide the best care possible. That said, being heterosexual, sometimes it’s harder for you to relate to and be able to counsel someone on things that would be of greater interest to them.” – Family medicine resident (MD8).

The presence of parents at adolescents’ healthcare visits often precluded youth from disclosing their sexual orientation. In many cases, adolescents were not “out” to their parents and did not want their parents to know they did not identify as straight.

“I would not have ever been able to talk about this stuff anywhere at any time. It’s something that I would just keep to myself. When I went to the doctor, and I was aware of my sexuality, I would probably have not mentioned it at all, because I wasn’t out, and my parents didn’t know.” –Lesbian female (YA5).

“It’s always that mild fear as a child, or young adolescent, if I say it to my doctor, will they disclose that to my parents, for example. Which isn’t to say my parents would be super bigoted or anything, but it’s more along the lines of, if I was going to come out to them, I want it to be on my terms, not through a doctor feeling like parents need to know something that I haven’t had the courage yet to tell them.” –Bisexual female (YA15).

“And they got to the question of my sexual orientation. But I was not comfortable coming out to them, because at the time, my parents were with me. Even if they were in the other room, I didn’t want them to accidently reveal to them that I was gay, because that could have been a detriment to my well-being, my financial health. They could have easily like abandoned me or just left me on the streets, because of – they’re a very traditional family.” –Gay male (YA11).

Physicians generally argued that providing a space for patients to talk safely without parents present was an important aspect of communicating with patients and the provision of effective care. Many spoke from specific clinical experiences.

“I think some kids haven't come out to the parents, and have a hard time when they're in our office, and the parents are not willing to leave the room, or they're worried that after the visit, they would get anything in writing or their insurance, related to the care they received that could point to the fact that they disclosed to the provider that they were gay or lesbian. So I think that’s one of the biggest hurdles that they have.” –Pediatrician (MD21).

Language used during healthcare visits could represent a barrier to or facilitator of effective communication between LGBQ patients and physicians. LGBQ youth wanted clinicians to help them feel comfortable during healthcare visits by addressing the broader socio-cultural context of their lives. Communicating LGBQ-specific knowledge either directly or through showing interest indicated to patients that physicians were capable and experienced with the health of sexual minorities and, therefore, represented a safe place to glean information and discuss their concerns.

“I still am very much exploring it [my sexuality]. I think it would be really cool if I had access to a long-term care provider that I could really sit down and talk about my life with. Someone I can communicate with, and someone that is a good listener. And maybe even takes notes on those things. If I disclose that [I’m] queer, that maybe I’m struggling with a certain aspect of that, or I have questions about something, that’s something that they would care enough to keep checking up on.” –Queer female (YA16).

“…just being really understanding of where we’re coming from, and the experiences that might be different in their lives as opposed to that of someone who is heterosexual.” –Bisexual female (YA22).

In addition, LGBQ youth wanted providers to remain friendly, open-minded, non-judgmental, and comfortable (i.e., not awkward) in their verbal and non-verbal communications during discussions about LGBQ-specific issues.

“Just be very friendly, very open. Please don’t be judgmental or awkward about anything. Act like you know how to deal with us. Don’t be like, ‘Oh, OK. I’m cool with the gay people!’.” –Gay male (YA11).

“The ability to not look surprised when I mention the fact that I’m gay. If I say I’m gay, don’t ask me if I’m sure.” –Bisexual female (YA20).

“I just think their body language, their facial expressions, their tone of voice, the words that they use – all of those things are hints as to how they feel about it when they review that stuff with you.” – Bisexual female (YA22).

Providers recognized the importance of language, and many expressed concerns about knowing and using appropriate language with LGBQ patients.

“I am heterosexual, and so sometimes I have a hard time finding the right words to make maybe a patient feel better or feel more comfortable. I want to be able to show an understanding and empathy, but it’s not something that I had gone through myself as a teenager. And so that’s probably a weaker area, just trying to find the right words to help them through whatever challenge they’re going through.” –Pediatric resident (MD11).

“Some of it really is almost like language. So when we have a deaf person or we have a Spanish speaker or someone else come in here, now, we are required to get a translator (…). So there are things that just allow communication to take place. I don’t know that there’s an analogy for sexual orientation, but that would be one thing – if there was a way to sort of speak the same language. It’s easier to do for those different cultures than it is for something like this.” –Family medicine physician (MD24).

We sought to address gaps in the literature regarding effective communication between LGBQ youth and healthcare providers by triangulating data from individual interviews with both samples. Overall, findings showed several commonalities, and a couple differences, in patients’ and providers’ perspectives regarding facilitators and barriers to communication. LGBQ youth expressed fears of judgment by providers, particularly during adolescence, and providers acknowledged that LGBQ patients likely possess such fears. The presence of parents during healthcare visits represented a barrier to open, honest communication for patients and providers. Both samples agreed language represented an important issue, yet they conceived this issue differently. Patients expressed concerns and desires related to providers communicating LGBQ - specific knowledge through their questions and anticipatory guidance, as well as showing comfort and acceptance through their non - verbal behaviors. In contrast, providers focused on whether or not they possessed the vocabulary to communicate respectfully with LGBQ patients. Further, our data showed a discrepancy between patients’ consistent desire for providers to broach the topic of sexual orientation, and the mixed perspectives held by providers about who should initiate this conversation and when he/she should do so.

Our findings support previous research showing sexual minority youth are unlikely to initiate conversations about sexual orientation, in part, due to fear of bias from physicians [7]. Therefore, clinicians must initiate these communications. However, our findings indicate clinicians often rely on youth to disclose their sexual orientation, possibly by expecting patients to make specific comments or ask questions that reveal their sexual orientation [25]. This finding is consistent with research showing up to 83% of pediatricians do not ask patients about their sexual orientation [26], sometimes not even if the young person presented with depression or suicidality [8]. Not learning a patient’s sexual orientation has significant implications, including leading to barriers engaging in meaningful conversations related to preventive medicine, health education, and anticipatory guidance.

Limited communication may occur because healthcare providers want to avoid making assumptions and appearing judgmental by remaining professionally neutral [27]. For example, several physicians in our study thought patients should initiate this disclosure or knowing patients’ sexual orientation was only important during physical/well visits. However, as Mc Nair and Hegarty [28] argue, attempted neutrality can contribute to homophobia, veils heteronormativity embedded within the healthcare system and clinical environment, and represents a barrier to disclosure of one’s sexual orientation, which obscures the presence of LGBQ patients and their unique healthcare needs. In short, remaining neutral is impossible, and avoiding labels reinforces the heterosexual assumption and status quo within healthcare [27]. In contrast, research shows LGBQ individuals perceive clinician assumptions that patients may not be heterosexual as acknowledgements that make visible and validate sexual identities and relationships [27]. According to the youth in our study, directly asking about patients’ sexual orientation and discussing LGBQ - specific health issues fosters feelings of comfort and perceptions of physician competence. Future research should build on our findings by exploring how clinical interventions and physician training could enhance facilitators and reduce barriers to effective provider - LGBQ patient communication, especially in the areas of disclosure and language.

Findings should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. Although our patient sample showed diversity in race/ethnicity, sex, and sexual orientation, our provider sample was more homogenous. The use of non – provider - patient dyads may be perceived as a limitation. However, our approach represents a strength by allowing LGBQ patients to relate experiences with different providers, and providers to relate their approach with multiple LGBQ patients. The non - dyad approach offered more freedom for both samples to express a range of experiences and examples of clinical encounters. Finally, the provider sample mainly included residents because of difficulties recruiting providers in - practice. Nevertheless, provider data showed consistency in responses between residents and practicing physicians, regardless of year in residency or years in practice.

Findings suggest LGBQ youth and healthcare providers share some similar and some dissimilar perspectives on barriers and facilitators to communicating effectively. In particular, the samples’ perspectives differed regarding the conception of language and discussions about sexual orientation during clinical encounters. Patients perceived providers as more educated and competent if they initiated conversations about patients’ sexual orientation, addressed LGBQ - specific issues, and provided LGBQ - specific health education. Insights gleaned from our samples fill gaps in the literature regarding patient - provider communication regarding sexual orientation and have implications for improving patient - centered care for LGBQ youth.

Healthcare providers who work with young people may need additional training focused on communicating effectively with LGBQ patients and clinic protocols for querying sexual orientation with all patients in a non - judgmental manner. In particular, clinicians should understand the importance of knowing patients’ sexual orientation for providing patient - centered care that includes appropriate anticipatory guidance and health education. They might benefit from learning how to initiate conversations about sexual orientation, rather than relying on patients to self - disclose, and respond without judgment. Non - judgmental responses involve verbal and non - verbal body language that helps ensure patients feel comfortable, safe, and accepted during healthcare visits.

Funding was provided from the University of Central Florida, College of Medicine to the first author.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Copyright: © 2019 Lindsay A Taliaferro., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.