Chukwuemeka Ngozi Onyearugha1, Nneka Chioma Okoronkwo1* and P E Onyemachi2

1Consultant Paediatrician, Senior Lecturer, Department of Paediatrics, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Abia State, Nigeria

2Consultant Community Physician, Senior Lecturer, Department of Community Medicine, Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba, Abia State, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Dr Nneka Okoronkwo, Consultant Paediatrician, Senior Lecturer, Department of Paediatrics, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Abia State, Nigeria.

Received: July 29, 2019; Published: August 23, 2019

Citation: Chukwuemeka Ngozi Onyearugha., et al. “Febrile Seizures at a Tertiary Paediatric Heath Facility in South-East Nigeria”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.9 (2019):47-51.

Background: Febrile convulsion being the commonest childhood neurological disorder worldwide is a medical emergency and source of concern to parents and caregivers. In the tropics, some harmful prehospital managements are still practiced before coming to health facilities. This study is aimed at determining the prevalence, aetiology and related factors of febrile convulsion at Aba, Nigeria.

Methods: All admissions of febrile convulsions at the Department of Paediatrics of Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba, from 1st January 2011 to 31st December 2016, were retrospectively analyzed

Results: The overall admissions over the study period were 1360 with 78 cases of febrile convulsion and a prevalence of 5.7%. The male: female ratio was 1.4: 1. Complex febrile seizures occurred in 18(23.1%) of patients and simple febrile seizures in 60 (76.9%). Majority 34(46.3%) were in the age bracket of 13-24 months, whereas 25 - 36 months and 6-12 months age brackets constituted 21.8% and 20.5% of cases respectively. The leading aetiologies were malaria (52.6%), bronchopneumonia (28.4%), and tonsillitis (14%). The modalities of pre-hospital management were application of palm kernel oil 17.9%, herbal medications 16.2%, administration of patent medicine dealers’ prescription 14.2%, and crude oil application 12.8% respectively.

Majority (92.3%) of the patients were discharged while mortality was 4%.

Conclusion: Our study reveals a prevalence rate of 5.4% for febrile seizures, with malaria as the greatest aetiology. The pre-hospital management comprised harmful practices by the caregivers.

Keywords: Febrile Seizure; Prevalence; Aetiology; Aba

Febrile convulsion is the most common paediatric neurological disorder all over the world, particularly in the tropics [1]. It occurs in 2 to 7% of individuals before the age of 5 years [2]. American Academy of Paediatrics defines febrile seizure (F S) as a seizure occurring in children between the ages of 6 and 60 months who do not have an intracranial infection, metabolic disturbance or history of afebrile seizure [3]. Febrile seizure is divided into two types viz:

Simple and complex febrile seizures. Simple febrile seizure is characterized by generalized tonic clonic activity without focal features, lasts less than 10 minutes without a recurrence within the next 24 hours and resolves spontaneously [3]. Complex febrile seizure is characterized by one or more of the following: partial (focal) onset or showing focal features during the seizure, lasting greater than 10–15 minutes, and recurring within 24 hours or within the same illness [4]. Most cases of febrile seizures are benign and self-limiting and in general, treatment is not recommended [3].

Prevalence of febrile seizures varies widely and is greatest in the tropics [1]. Prevalence of 5-10% is reported in India, 2-5% in the United States and United Kingdom [5] and 10-18% in Nigeria [6]. FS is universally reported to occur more in males than females, with a male: female ratio of 1.1: 1 to 2:1 [7]. Most febrile seizures (70-75%) are simple FS while 9-35% are complex [8]. FS is mostly generalized convulsive but about 5% is reported to be non-convulsive but presenting with loss of consciousness, starring, eye deviation, atonia and cyanosis [9]. When the excitatory effect is mildly greater than the inhibitory effect, simple febrile seizure occurs and when the excitatory effect is much higher, complex FS occurs [10].

Febrile seizure may also be familial in occurrence [11,12]. Familial studies show occurrence of 10-46% in children with positive family history of FS [12]. Higher concordance rate has also been observed in monozygotic twins with febrile seizure than dizygotic twins [12].

There is often inappropriate prehospital management of febrile seizures in tropical countries [6] where the prevalence is greatest. FS elicits anxiety, fear and panicky measures among the caregivers of children during the episode. Harmful practices including applying substances to the eyes, incisions on the body, burning of the feet or buttocks are still carried out on these children and often constitute persistent morbidities which could result even in death [6,13].

This study was therefore, undertaken to evaluate the prevalence, aetiology, management and related factors of febrile seizure as seen at the Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba, Abia State.

All children aged 6 months to 5 years who had febrile seizure, admitted to Abia State University Teaching Hospital from 1st January 2011 to 31st December 2016 were retrospectively analyzed.

The study was conducted at the Abia State University Teaching Hospital (ABSUTH), Aba, Southeast Nigeria. The hospital serves as a tertiary health care institution and referral centre for peripheral hospitals in Aba and neighboring states of Rivers, Akwa-Ibom and Imo states.

The Department of Paediatrics is manned by 6 consultants, 12 registrars and 10 house officers (who do 3 monthly rotation before proceeding to other departments). All cases of admission were reviewed by the registrar on call at presentation to the hospital. Diagnosis was made on patients based on clinical features and laboratory results.

The admission registers of the children emergency and main paediatrics wards were perused and case file numbers of patients with febrile seizures were noted and the case notes subsequently retrieved from the Medical Records Department. Information extracted included age, gender, seizure type, seizure recurrence, family history, aetiology, prehospital management and outcome. Simple febrile seizure was diagnosed as seizure that occurred during a febrile episode, generalized tonic clonic, lasting less than 10 minutes and occurring once with full regaining of consciousness after the seizure. Complex febrile seizure was defined as seizure lasting more than 15 minutes and/or occurring more than once with normal cerebrospinal fluid (no bacterial isolates; nor presence of pleocytosis, reduced CSF glucose and elevated protein).

The total admission over the study period was documented

Data collected were analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0. Frequency tables, means and percentages were generated for all variables of interest.

The overall number of admissions within the age bracket during the study period was 1360 out of which 75 had inadequate data and were discarded. One thousand, two hundred and eighty-five (1285) admissions were used for further analysis. Seventy-eight patients had febrile seizure giving a prevalence of 5.7%. Eighteen of the 78 patients with febrile seizures had complex febrile seizure constituting 23.1%, while 76.9% had simple FS. There were 46 males and 32 females with seizure, giving a male: female ratio of 1.4:1.

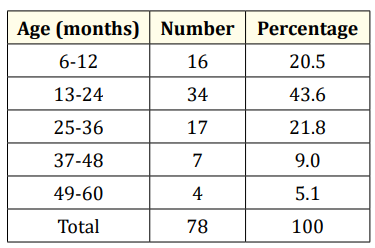

Major proportion, 34 (43.6%), of the children with febrile seizure was the 13-24 months age group, while 6-12 months and 2536 months age brackets constituted 20.5% and 21.8% respectively (Table 1).

Table 1: Age of patients with seizure.

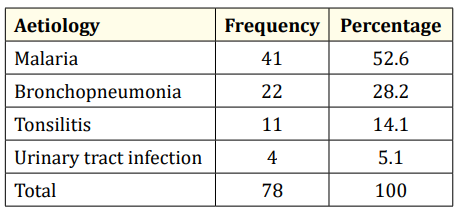

The leading aetiologies of febrile seizures were malaria (52.6%) and bronchopneumonia 28.4% (Table 2).

Table 2: Aetiology of febrile seizures.

Table 3 demonstrates the pre-hospital management of febrile seizures. Application of palm kernel oil 14 (17.9%), use of herbal medications 13 (16.7%), patent medicine dealers’ prescription 11 (14%) and crude oil application were the leading modalities of prehospital management.

Table 3: Prehospital management of febrile seizure.

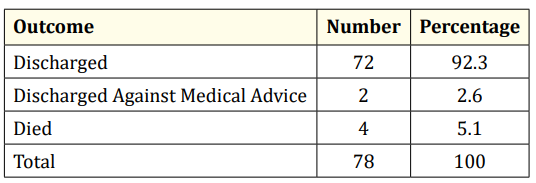

Seventy-two (92.3%) of the patients were discharged while 4 (5.1%) died.

Table 4: Outcome of admission.

The prevalence obtained from this study was 5.7%. This is within the range of 5-10 % reported in India [14] but less than 10-18% reported from different parts of Nigeria [13,15]. Lower prevalence reported in our study could be explained by the location of several peripheral clinics in the commercial city of Aba. These patients are more conveniently taken by panic-stricken caregivers to nearby clinics instead of the Teaching Hospital. Also, the belief that parenteral treatment is not given to a convulsing child is rife among the populace here, so they often resort to herbal medication rather than orthodox management.

It was also observed in this survey that 23.1% of the febrile seizures were complex febrile seizures. This value is in consonance with previous reports [15]. Our analysis demonstrates that the male: female ratio of the patients that had seizure was 1.4: 1. This also corroborates previous findings of male: female ratio of patients with febrile seizures being in the range of 1.1:1 to 2: 1 [15].

This study shows that the largest proportion of patients (43.6%) were in the 12-24 months age bracket, while 85.9% were in the 6 to 36 months age category. Universally, previous reports noted that most cases of FS occur within the first 3 years of life with a peak at 12 to 18 months [9]. Though our tabulation did not specify 12 to 18 months age bracket in the frequency of occurrence, our findings still tend to corroborate previous reports. Febrile seizure has been described as an age-dependent response of the immature brain to fever [16]. During the maturation process, there is an enhanced neuronal excitability that predisposes the child to febrile seizures. As such, febrile seizures occur mainly in children before the age of 3 years when the seizure threshold is low [16].

Malaria has been consistently reported to be the leading aetiology of febrile seizure in sub-Sahara Africa [17-19]. Our survey reveals malaria as the leading aetiology of febrile seizure thus corroborating that observation. This could be explained by the fact that Nigeria has the highest global burden of malaria disease. World Health Organization in her 2018 report, indicated that in 2017, five countries accounted for nearly half of all malaria cases worldwide, with Nigeria (25%) having the highest incidence [20].

Inappropriate prehospital management of febrile seizures characterizes the management approach in many tropical countries where FS is most prevalent, in contrast with more developed countries. Application of palm kernel oil, use of herbal medications and even crude oil as drops to the mouth and application to the body, are the leading home management modalities of seizures noted in this analysis. The use of herbal medications in this study is like the prehospital management in Sokoto, north west Nigeria [21] but in contrasts with the practice in Ibadan, southwest Nigeria where cow’s urine is the major substance administered orally and applied to the body [13]. Herbal medications have been noted to cause hepatic injury among other adverse effects [22,23]. Heavy metals such as cadmium, copper, iron, nickel, selenium, zinc, lead and mercury some of which can be quite toxic to organs of the body were identified in a random sample of Nigerian traditional products [24]. Moreover, the unhygienic preparation method and non-regulated dose of these products make them the more harmful. Crude oil which was also observed to be in substantial use in this study has been documented to cause pneumonitis and central nervous system complications [25].

Quite often, the morbidity arising from prehospital mismanagement of these patients is worse than the febrile seizure itself, which in most cases has a benign outcome. Olowu and Olanrewaju noted that morbidity and mortality in relation to febrile seizures were directly related to administration of traditional concoctions prior to admission [26].

Overwhelming majority (92.3%) of the patients were discharged and 5.1% suffered mortality in this study. This conforms with universal reports in previous studies [6,27]. Our discharge rate of this magnitude could also be explained by the fact that the aetiologies particularly malaria and bronchopneumonia responded favorably to treatment.

Prevalence of febrile seizures was 5.7%. Malaria was the leading cause. Harmful prehospital management was rife in the community. There should be widespread education of the citizenry on basic malaria preventive measures and the dangers associated with their prehospital management approach of febrile convulsion.

None

Authors have nothing to declare.

Our profound gratitude goes to the nursing staff of the Children Emergency Room, Main Paediatrics Wards and staff of the Medical Records Department for their cooperation during data collection.

Copyright: © 2019 Chukwuemeka Ngozi Onyearugha., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.