Hisham Abdelrhim*

Department of Pediatrics, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Plymouth University Hospitals, England, UK

*Corresponding Author: Hisham Abdelrhim, Department of Pediatrics, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Plymouth University hospitals, England, UK.

Received: April 29, 2019; Published: July 10, 2019

Citation: Hisham Abdelrhim. “A Retrospective Observational Survey for Assessment of The Service Quality of Lumbar Punctures in Neonates ”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.8 (2019):13-18.

The incidence of early onset (< 72 h) neonatal bacterial meningitis (EONM) was estimated to be less than 0,3 per 1000 live births. The National Institute of Care and Excellence (NICE) guidelines CG149 states that a raised CRP more than 10 10 mg/dl in infants at the risk of early onset neonatal sepsis is an indication for Lumbar puncture. Despite of the high rate of doing (lumbar puncture) LP in neonatal units, the yield is very low.

Keywords: Punctures; Neonates; Lumbar Puncture

Neonatal meningitis has high mortality and morbidity [1]. Symptoms are often subtle and lumbar puncture is the only way to confirm. The clinical features of early onset neonatal meningitis (EOM) appear during the first week of life, while late onset neonatal meningitis (LOM) occurs in 8–28 postnatal days [1,2].

Every year there are 15,000 -30,000 newborn babies undergo lumbar puncture (LP) as a diagnostic test of meningitis. The success rate of the lumbar puncture procedures is 50 - 60% which means thousands of babies have unsuccessful procedures requiring repeat procedures, causing distress to the baby and parents, and often necessitating prolonged course of antibiotics and stay in the hospital [3,4] A retrospective chart review of 355 LP procedures performed in a big tertiary neonatal unit has shown that the success rate of LP procedures was independent of the experience and hand skills of the neonatal provider for the procedure [5].

We present here a retrospective observational survey at 2 different hospital settings. The aim of this was to determine the need for LP as a diagnostic procedure of meningitis in newborns with increased C-reactive protein (CRP) and whether the age of presentation (<7 or >7 days) should influence the decision to perform LP.

Design, setting, and patients

This retrospective observational survey was conducted in a busy tertiary hospital. We reviewed medical notes and laboratory records on all LP procedures which were completed and documented for babies less than 28 days old, in the neonatal unit and children’s ward, from August 1, 2015, to July 31, 2016. However, babies with incomplete records and those who underwent therapeutic LP were excluded from the analysis.

The medical notes were examined for gestational age (GA), gender, birth weight, onset of infection, risk factors such as prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM) (>18 hours), mother’s vaginitis and asymptomatic bacteriuria, prematurity (GA < 37 week), low birth weight (LBW, i.e., < 2500 g), multiple birth pregnancy, and asphyxia were reviewed, as well as clinical findings such as fever, irritability, seizures, lethargy, food refusal, bulging fontanels, moaning, tachypnea, cyanosis, abdominal distension, vomiting, apnea, jaundice, skin lesions, opisthotonos, diarrhea, hypothermia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and metabolic disorders. Laboratory findings such as CSF analysis and blood and CSF cultures were also assessed for every baby included in the study. We looked at the vital data before and after the procedure which were plotted on the Newborn Early Warning (NEW) system [15].

Should a baby have any of the above symptoms or abnormal records on the NEW system, he/she will be considered symptomatic. Each case of meningitis was counted as one case even if the infant underwent multiple LPs.

The following criteria were used to diagnose meningitis in our study: (1) positive CSF culture (major), (2) the organism seen under microscopy by gram stain (major), (3) > 20 CSF white blood cells (WBCs) in a clear sample (major), (4) >20 CSF WBCs in a blood-stained sample (minor), (5) presence of symptoms (see list of symptoms earlier) (minor), and (6) positive blood culture (minor). Diagnosis of meningitis required one major or two minor criteria, or one major and one minor criterion. Having only one minor criterion meant “probable meningitis”. Probable meningitis received a course of antibiotics (5 -10 days). The diagnosis of viral meningitis, on the other hand, was based on a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the patient’s CSF.

All meningitis cases received appropriate antibiotic treatment intravenously for 10 or more days. A false-positive (contaminated) culture was defined by the growth of an organism without CSF pleocytosis or positive Gram stain together with a clinical picture not suggestive of meningitis. A traumatic blood-stained CSF was considered when the sample was grossly blood stained or the counted red blood cells in the CSF was more than 1000 cells/mm3.

The babies were categorized into three groups: the healthy group(asymptomatic), the unhealthy non-meningitis group(symptomatic), and the meningitis group. The healthy group included term babies who were clinically doing well but had LP due to a CRP rise >10 mg/dL. The specific criteria for the healthy group were as follows: (1) LP done within the first week of life, (2) term gestation, (3) weight >2.5 kg, (4) normal records on the NEW system, (5) no clinical signs or symptoms of meningitis (see above), and (6) negative blood culture. The unhealthy nonmeningitis group consisted of babies who had an abnormal clinical picture and/or abnormal records on the NEW system and/or a positive blood culture they had other diagnoses such as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), congenital pneumonia and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE).

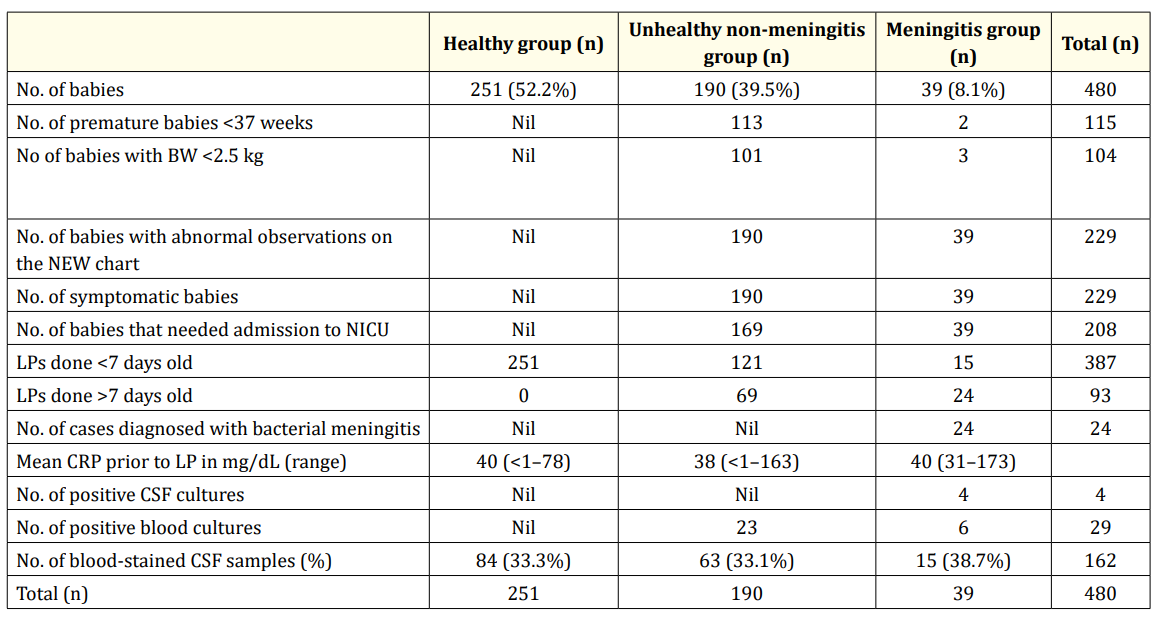

Overall, 527 LPs were completed and documented between August 1, 2015, and July 31, 2016. We excluded 47 cases because we did not find their notes. Among 480 LPs, 360 were performed before day 7 of life, and 120 were done between day 8 and 28. A total of 159 LPs (33%) yielded blood-stained samples (many of those were heavily blood stained, thus not suitable for WCCs counting and protein analysis).

A total of 39 patients were diagnosed with meningitis and probable meningitis; 15 had EONM, 9 had LONM, and 15 had viral meningitis (positive viral PCR in the CSF).

In our study population, the maternal risk factors for meningitis were premature rupture of membranes (PROM), mother’s vaginitis during the third trimester, asymptomatic bacteriuria, and presumed chorioamnionitis, while the neonatal risk factors for NM were prematurity, LBW, multiple birth pregnancy, and asphyxia.

The indications for LP were rising CRP (>10 mg/dL) in 401 (83.7%) patients, seizures in 32 (6.6%), fever and positive blood culture in 29 (6%), and confirmed sepsis-like manifestations in 18 (3.7%). The working diagnoses were suspected sepsis with negative blood culture in 374 patients, neonatal sepsis (proven) in 29 cases, RDS in 41, congenital pneumonia in 9, urinary tract infection in 8, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in 13, neonatal seizures in 5, and transient neonatal hyperammonemia in 1.

All meningitis cases were symptomatic, the clinical findings included seizures in 20 (51%) babies , tachypnea in 21 (54%) babies, fever in 11 (28%) babies, irritability in 4 (10%) babies, icter in 4 (10%) babies, and bulging of fontanel in 2 (5%) babies. The mean CSF leukocyte count was 247±133 cells/mm3. CSF cultures were positive in 4 patients, and pathogens included GBS in one baby, E. coli in one baby, and toxoplasma in 2 babies. The PCR test was positive for enteroviruses in 15 cases. Blood cultures were performed for all patients, 6 patients (15%) had positive blood cultures with the same organisms in the CSF cultures in 2 babies only.

Table 1: BW, birth weight; NEW, Newborn Early Warning system; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; LP, lumbar puncture; CRP, C-reactive protein; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid

Study was undertaken to determine whether it is rationale to do LP in every newborn having raised CRP more than 10 mg/dl as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline CG149 which was published in August 2012 or not?200 And does the age at presentation (<72 hours or >72 hours) influence the decision to do lumbar puncture.

We reviewed the records of the microbiology laboratory at a general District Hospital, in the United Kingdom, to identify all neonates who underwent LPs between January 2003 and December 2012. All identified neonates had their medical notes reviewed for the clinical course prior to and after the LP procedure. We also identified and reviewed all medical records of babies who were labelled meningitis or central nervous system infection.

Those with incomplete records or had the LP procedure past the neonatal period were excluded from the analysis. Abnormal CSF findings considered indicative of meningitis were cell count >20 leucocytes/ mm3 and/or a positive Gram stain with only one type of staining characteristic, or a pure growth of only one organism. The infants were classified into 2 groups (Early or Late) based on the age when the lumbar puncture was performed (<72 h, >72 h). Medical records were examined for signs suggestive of sepsis or meningitis (i.e. lethargy, hypothermia, hypotonia, poor perfusion or apnoea), or specific neurological signs such as jitteriness and seizures, which cannot be fully explained by hypoglycaemia or hypocalcaemia, or severe perinatal asphyxia (5* apgar score <3), or if there were any abnormal observation on the NEW system. A healthy well doing neonate is defined as term asymptomatic babies with normal observation on the NEW system.

2351 neonates were admitted and 142 of them had LPs during the period between Jan 2003 and Dec 2012 in the course of sepsis and meningitis evaluation. Forty four infants were excluded from the study due to incomplete medical records (6), or unsuccessful LP (38) due to either a dry tap or CSF was heavily stained with blood, these babies were followed and none of these infants were diagnosed with meningitis.

There was no cases of meningitis among infants evaluated within the first 72 hours of life; whilst 18% of those evaluated after 72 hours had meningitis.

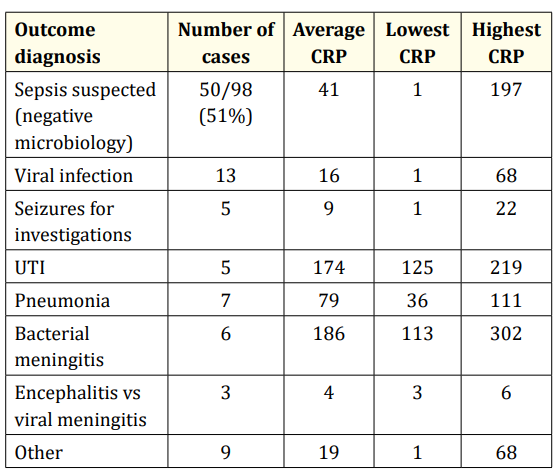

We estimated 98 LPs successfully performed to 98 babies to rule out meningitis in a total population of nearly 16000 babies born in the District Hospital between Jan 2003 and December 2012. The average number for attempts at each baby was three.

In the study population 11 blood cultures were positive out of which 5 were considered as contamination by the microbiology team mixed growth or coagulase negative staph in cases where there was no central lines or devices 6/98 (6%).

Table 2

Although the occurrence of neonatal meningitis is uncommon, it remains a devastating infection with high mortality and high morbidity. The incidence of neonatal meningitis is estimated to be 0.3 per 1000 live births [6].

Meningitis is estimated to occur in approximately 1–2% of suspected cases of sepsis within the first 72 h of life, or early-onset sepsis, though the risk is limited almost entirely to symptomatic infants.7 In survey 1, over 12 months there were 24 babies diagnosed with NBM, in a tertiary hospital with delivery rates of around 8,000 deliveries per year that makes the incidence of NBM 5 in every 1000 live born babies. Although that seems higher than the national statistics there has been only 4 cases with microbiologically confirmed meningitis out of which there was only one case of EONM which presented on day 5 of life with sepsis-like manifestations and hydrocephalic changes on the cranial ultrasound scan. The CSF was positive for toxoplasma. In survey 2, over the course of 10 years there were 16,000 live born babies, lumbar punctures were attempted in 146 babies (0.9%), and only 6 (0.04%) were diagnosed with NBM who were all LONM. We do not have an explanation for why the prevalence of NBM in the tertiary hospital is 10 times higher than in the district hospital though the incidence EONBM was almost zero in both settings.

The incidence of HSV meningitis is estimated to be 0.02–0.5 cases per 1000 live births [7]. With improved laboratory procedures, viral NM is now being recognized and contributes to the overall incidence of NM. Recent studies reported the incidence of viral meningitis in neonates as 0.05/1000 live births. In our study the cases diagnosed with viral meningitis contributed to more than third of the meningitis cases.

A definitive diagnosis of NBM is made by CSF examination via LP, which should be performed in any neonate with proven sepsis or suspected of having meningitis or late onset sepsis. LP can be challenging to perform in a neonate and may yield data that are difficult to interpret In our study the vast majority of the LP procedures were done due to having a CRP rise (80%), only few had the procedures due to being symptomatic or having a positive blood culture The American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement on suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis supports performing LP as part of the sepsis evaluation of the neonate with symptoms concerning for early-onset sepsis, but recommends a more limited evaluation in the asymptomatic neonate with sepsis risk factors [8]. The NICE guidance CG149 put a CRP of 10 mg/dl as a cut off for performing LP in babies at the risk of sepsis. This led the units to perform far more LPs than previously and subsequently caused increased antibiotics use and prolonged hospitalization in a time concerns are escalating about the antibiotics resistance and limited NHS resources [9]. This highlights the need to rationalize the indications of LP in newborn babies.

A study was conducted in the pediatric department of University of Ilorin, which reviewed the laboratory and medical records of 506 infants who had LPs between January 1988 and December 1990. Neonates <72 hours of age accounted for 52% of all LPs with no detected cases of meningitis. This led to a policy shift from routinely performing LPs to reserving them for infants with signs of sepsis. This new policy was monitored prospectively from July 1991 to December 1993. Three times fewer procedures were performed in neonates <72 hours, and there was no diagnosed or missed case of meningitis [10].

Another point to consider before doing the LP is traumatic taps and unsuccessful lumbar punctures are quite frequent occurrences in the neonate. The success rate of the LP procedures was 67% in our study. The average number of attempts on every baby were 3, and only 98 were successful from a total of 151 had the LP procedures. LP is considered successful when a sufficient amount of non bloody cerebrospinal fluid is collected.

In both of our surveys, although the most common reason for performing the LP procedures was raised CRP none of the term asymptomatic babies, with a birth weight > 2.5 kg, with normal records on the NEW system and had LPs during the first week of life only due to raised CRP, had meningitis or microbiologically proved sepsis. On the other hand, all meningitis babies were obviously symptomatic with abnormal records on the NEW system.

C reactive protein (CRP) is the most sensitive of the acute-phase proteins, levels begin to rise within 4–6 hours from the onset of signs of infection or tissue injury and peak hours later. They rapidly disappear as the infection or inflammatory process resolves [11,12]. The degree of CRP response or rise in serum may be dependent on the amount of tissue damage present. For example, elevated CRP levels from 150 to 350 mg/L have been reported in cases of invasive bacterial meningitis, whereas smaller rises from 20 to 40 mg/L occur in acute viral infections and from noninfectious causes [11,13]. Our study showed that all cases who had bacterial meningitis had CRP levels between 113 and 302 mg/dL; whilst, in viral meningitis cases, the CRP ranged between <1 and 40 mg/dL.

Clinically one cannot easily make a specific diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in neonates. Thus, in babies with any clinical features suggestive of infection (and certainly in babies with positive blood cultures), an LP and evaluation of the CSF is vital. Research data show that pretreatment with antibiotics 12–72 h before the LP is performed will significantly increase glucose and decrease protein in the CSF as compared with no pretreatment with antibiotics. However, antibiotics have no influence on CSF WBCs so that pretreatment with antibiotics should not prevent a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis from being made [14]. Pretreatment will, however, have an impact on CSF culture results and may therefore impair a specific etiological diagnosis. PCR is the most widely used non-culture method of pathogen detection, although its routine use in the context of neonatal infection is currently limited [14,15].

CRP rise in newborn babies at the risk of neonatal sepsis is not enough to justify doing LP routinely for every case with raised CRP if the baby is clinically asymptomatic. Given that meningitis is a rare condition particularly within the first 72 hours of life and the yield of lumbar puncture is virtually zero, we recommend that lumbar punctures be reserved for selected infants. The clinical setting and probability of meningitis are important determinants of the likely value of LP. For the term asymptomatic neonates with normal NEW records and obstetric risk factors for early-onset sepsis and have moderately raised CRP (<40 mg/dL), LP may be delayed and only performed if the CRP continues to rise despite treatment or if a blood culture is positive. On the other hand, infants with suspected late-onset sepsis should have a low threshold for performing LP.

Copyright: © 2019 Hisham Abdelrhim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.