Ankit Patel1, Sameer Ruparel2*, Tarun Dusad1, Gaurav Mehta2 and Vishal Kundnani3

1M.S. Orthopaedics, Clinical Spine Fellow- Bombay Hospital, Mumbai, India

2M.S. Orthopaedics, DNB Orthopaedics, Clinical Spine Fellow- Bombay Hospital, Mumbai, India

3M.S. Orthopaedics, Consultant Spine Surgeon, Chief- Mumbai Institute of Spine Surgery [MISS], Bombay Hospital, Mumbai, India

*Corresponding Author: Sameer Ruparel, Clinical Spine Fellow- Bombay Hospital, Mumbai, India.

Received: April 09, 2019; Published: June 28, 2019

Citation: Sameer Ruparel., et al. “Apical Spinal Osteotomy in Paediatric Patients for Severe Rigid Kyphoscoliosis- Long Term Clinic-Radiological Efficacy”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.7 (2019): 30-40.

Object: Spinal osteotomy in paediatric patients is challenging due to various factors. For correction of severe rigid kyphoscoliosis in children, numerous techniques with anterior/posterior or combined approaches, multilevel osteotomies have been described which are associated with prolonged operative times and large amounts of blood loss. The purpose of this study is to highlight a modification to technique of ASO [Posterior only single level osteotomy] in paediatric patients with severe rigid kyphoscoliosis and to evaluate its clinico-radiological efficacy.

Methods: A retrospective study of 32 consecutive patients with severe rigid kyphoscoliosis operated by a single surgeon at a single institution over a period of 5 years were included. Inclusion criteria were patients with age < 14 years, rigid thoracic/thoracolumbar/ lumbar kyphosis [> 70 degrees] with/without neurological deficit and with/without scoliosis and a minimum follow up of 2 years. Patients with cervical or lumbo-sacral kyphosis were excluded from the study. Demographic and clinical parameters like age, sex, etiology, neurological examination status [Frankel grade], Visual Analogue Score [VAS] and Oswestry Disability Index [ODI] were noted. Operative parameters like level of osteotomy, number of levels fused, duration of surgery, blood loss and complications were recorded. Radiological assessment was done for pre op, post op and final Cobb’s angle for kyphosis and scoliosis. Similarly, correction of sagittal vertical axis [SVA] was calculated. Fusion was assessed in all patients at final follow up.

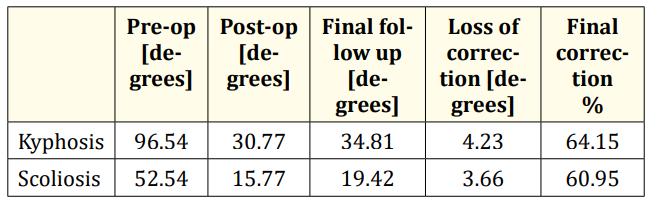

Results: 26 children [M: F=18:8] with a mean age of 9 years and minimum follow up of 2 years were available for analysis. Significant improvement [P value <0.05] in radiological, clinical and functional parameters [Cobb’s angle for scoliosis and kyphosis, SVA, VAS and ODI] was recorded. The mean pre-operative kyphotic Cobb’s angle was 96.54o which corrected to 34.81o indicating final average correction of 64.15% and average loss of 4.23o. Similarly, average scoliotic Cobb’s angle improved from 52.54o preoperatively to 19.42o with mean correction of 60.95% at final follow up. The preoperative SVA averaged 7.6 cm which improved to 3.94 cm at the end of 2 years. Bony fusion was achieved in all patients. The mean number of levels fused was 5.69. The mean operative time was 243.46 minutes with average intra-operative blood loss of 336.92 ml. Non neurological complications stood at 15.39% [2-dural tears, 1- superficial infection, 1- implant failure]. At the end of 2 years, all patients maintained or improved their neurological status except one who developed paraplegia immediately post-surgery and did not recover.

Conclusion: The present study analysed the clinico-radiological efficacy of apical spinal osteotomy [ASO] for severe rigid kyphoscoliosis in paediatric patients. To our knowledge, this study represents the largest series of paediatric patients with mean age of 9 years who have been managed with posterior approach single level ASO.

Keywords: Kyphosis; Scoliosis; Deformity Correction; Paediatric Deformity; Osteotomy; Posterior Approach

The correction of sagittal plane deformity in paediatric age group has been a contemporary and challenging subject for the spine surgeon and has gripped the curiosity of many in recent past [2,9]. Loss of normal sagittal balance produces a posture that is at biomechanical disadvantage and may cause spinal cord compression giving rise to neurological symptoms. The aim of surgery is to fuse the spine in a balanced position as close to normal configuration as possible with minimal morbidity and complications.

Correction of kyphoscoliosis can be achieved by a single posterior approach with the help closing wedge osteotomies [CWO] like Smith-Peterson osteotomy [SPO], Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy [PSO] and Vertebral Column Resection [VCR]. However, anatomic limitation of a vertebral body restricts CWO to about 35 degrees lordosis [5,12,18]. When sagittal imbalance exceeds 25 cm, consideration must be given to performing more than 1 CWO to obtain adequate correction [6]. Similarly, excessive shortening is dangerous since the spinal cord may then be too long for the shortened column and become kinked and potentially damaged. Gertzbein and Harris [12] recommended correction to 30-40 degrees.

For the correction of severe rigid deformities through a posterior approach and osteotomy at a single level, recently some authors have described modifications of conventional osteotomies like apical lordosating osteotomy [7], modified VCR [29], apical segmental resection osteotomy [10], and closing opening wedge osteotomy [8,14]. These surgical procedures have been associated with long operating hours and significant blood loss [8,14,29].

Spinal osteotomy in paediatric patients is challenging due to various factors- poor bone stock, rapid progression, lack of implants and suboptimal implant purchase. The purpose of this study is to highlight a modification to technique of Apical Spinal Osteotomy [ASO] [Posterior only single level osteotomy] in paediatric patients with severe rigid kyphoscoliosis and to evaluate its clinico-radiological efficacy.

32 consecutive patients [M: F=21:11] with kyphoscoliosis were operated at a single institution by a single surgeon over a period of six years [Nov 2009-Aug 2014]. Inclusion criteria were patients with age < 14 years, rigid thoracic/thoraco-lumbar/ lumbar kyphosis [> 70 degrees] with/without neurological deficit and with/without scoliosis and a minimum follow up of 2 years. Patients with cervical or lumbo-sacral kyphosis were excluded from the study. Data was collected and evaluated by an independent observer. Out of 32 patients, 3 were lost to follow up and 3 had less than required follow up and were excluded from analysis. Thus, 26 patients [M:F=18:8] were available for analysis. All patients underwent comprehensive clinic-radiological evaluation and demographic, clinical, neurological examination and radiological data was collected preoperatively and at follow up [immediate post-surgery, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and final follow up- 2 years]. The patients were evaluated by the operating surgeon and a junior spine surgeon whilst data was collected by two clinical spine fellows who were not a part of the operating team.

All patients were operated with three column spinal osteotomy at the apex of deformity- Apical Spinal Osteotomy [ASO] as described below.

Patients were placed prone under general anaesthesia on bolsters with padding of all bony prominences. The apex of deformity was placed over the hinge of the operating table so that when the osteotomy is closed, the table could move from flexed position to more neutral alignment if needed. Intra operative multi-modality neuro-monitoring [SSEP, MEP, EMG] was used in all patients. Posterior midline incision was taken and strict sub periosteal dissection was performed to avoid blood loss from upper to lower planned instrumented levels. Facets included in fusion levels were excised to promote intra-articular arthrodesis. Pedicle screws were inserted using freehand technique and C-arm guidance. Titanium 3.5mm, 4.5mm and 5.5 mm paediatric pedicle screw system was used for this purpose. Four points of fixation were secured before vertebral resection and were connected with a contoured rod on one side to provide stability.

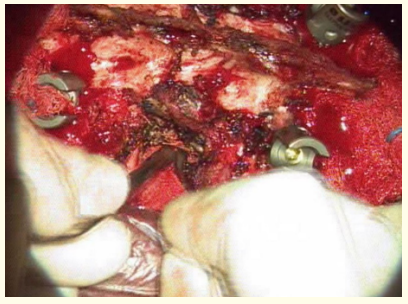

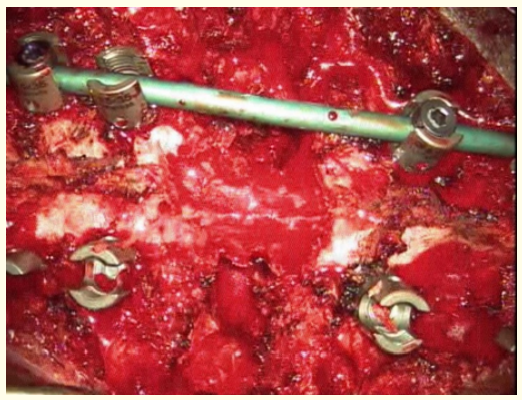

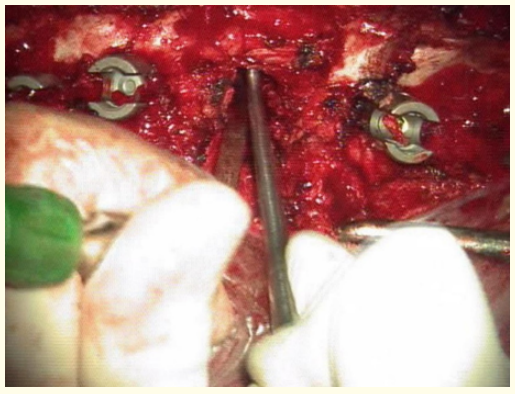

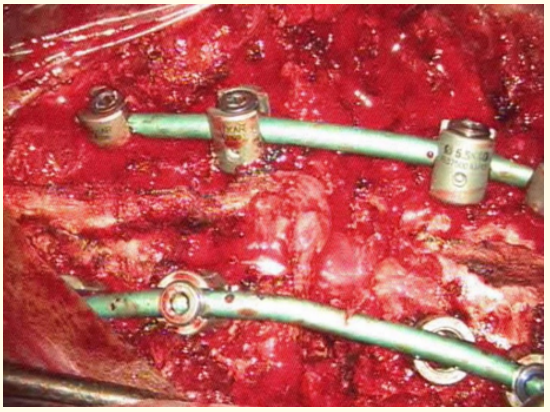

The resection was carried out at the apex of deformity utilizing the lever arm to the maximum. In cases of kyphosis with scoliosis, the width of osteotomy was broader on the convex side and posteriorly for correction of both sagittal and coronal plane deformity simultaneously. The transverse process and rib heads were removed to allow complete dissection of lateral wall of the vertebral body [Figure 1]. Segmental vessels in line of dissection were ligated and cut only on one side. Nerve roots in the thoracic region were sacrificed, if need be, though they were preserved throughout the procedure in the lumbar region. The lateral wall of pedicle was removed piecemeal. The vertebral body resection [Figure 2] was performed with the help of pituitary rongeurs, 4 mm cutting burr and curettes initially. Dissection was carried out until the anterior wall was removed keeping anterior longitudinal ligament, medial wall of pedicle and posterior wall of vertebral body intact. Temporary rod was fixed on the ipsilateral side and similar procedure was repeated on contralateral side. At the end of this process, a bony shell remained around the dural sac circumferentially [Figure 3]. At this stage, posterior vertebral wall anterior to the dural sac, medial pedicle wall and laminae on dorsal aspect of the dura were removed [Figure 4]. This step is performed when adequate amount of vertebral body is resected. We believe it helps in reducing the blood loss from epidural veins and protects the dural sac from injury during the resection procedure. The posterior cortex of the vertebral body was initially thinned out with a diamond burr and was then removed (pushed down) with the help of reverse angle curettes [Figure 5].

Figure 1: Meticulous sub-periosteal elevation off the lateral vertebral body & antero-lateral dissection with protection of pleural sac.

Figure 2: De-cancellation of vertebral body starting from the convex side.

Figure 3: Completion of de-cancellation and intact spinal canal giving an avascular field. (roller-gauze seen passing anterior to intact bony canal enclosing the dural sac).

Figure 4: Removal of posterior elements with kerrison ronguer and stabilization with rod on one side.

Figure 5: Breaking the posterior wall of vertebral body with reverse angled curette.

Deformity correction [Figures 6 and 7] was attempted by closure of osteotomy with sequential rod contouring. Gradual correction of kyphosis angle was attempted at every sequence of rod bending and extension of operating table if needed. In scoliosis, compression and shortening was done more on the convex side and was asymmetrical. Though mean arterial pressure was adequately maintained throughout the procedure, it is particularly important at this step to maintain spinal cord perfusion. End point of column shortening in our series was direct visualization of dural buckling, any NMEP/SSEP signal change or loss and more than 15 mm of closing of the wedge on convex side at posterior face of osteotomy.

Figure 6: Before closure after exchange with pre-contoured rod.

Figure 7: Closure of osteotomy the compression to correct deformity in both sagittal and coronal planes.

Posterior fusion was performed at all instrumented levels. The number of levels to fuse was decided intra operatively depending upon the extent of correction achieved and gap present anteriorly after osteotomy. If the gap was less than 10 mm and sufficient correction was achieved with bone on bone contact after closure of osteotomy, only 2 levels above and below were fused. 3 level above2 level below or 3 level above and below constructs were also used in few patients where needed. Considering that all patients were in the range of 6-14 years with significant number of thoracic deformities, efforts were made to save as many levels as possible and thus giving them a chance for better truncal height and pulmonary capacity at maturity. Anteriorly, if the residual bony defect after closing osteotomy/ column shortening was less than 10mm, autogenous cancellous chip bone was placed. If anterior gap was more than 10mm, titanium mesh cage filled with bone graft was placed. The cage was just fit for the anterior gap and did not cause anterior column lengthening. Additional compression over the cage was carried to lock it into place and maintain optimum correction. Wound closure was done in layers over negative suction drain.

Patients were allowed to sit up in bed within 24 hours. They were allowed to mobilize out of bed on the second post-operative day with brace support. Brace was recommended for a period of 6 weeks.

Statistical analysis was done using chi square test and student t-test for assessment of significance between variables. [P value < 0.05 was considered significant]. The authors engaged a biostatistician on this manuscript. A normal distribution was obtained and parametric tests were used.

26 children with a minimum follow up of 24 months [Mean =28.31 months, S.D= 5.14 months, Range= 24-48 months] were included in the study. The mean age was 9 years [SD=2.5 years, Range= 6-14 years]. There were 18 boys and 8 girls in the study.

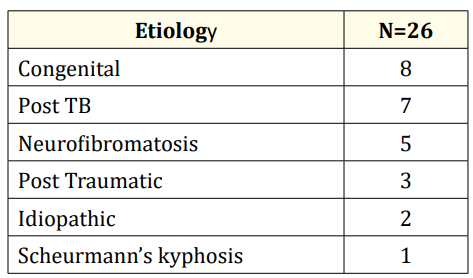

Our series included children affected due to varied etiologies [Table 1]. Congenital kyphoscoliotic deformity was diagnosed in 8 patients, kyphoscoliosis due to post tubercular infection in 7, neurofibromatosis in 5, post-traumatic kyphosis in 3, idiopathic kyphoscoliosis in 2 and Scheuermann’s kyphosis in 1 patient.

Table 1: Distribution of etiologies.

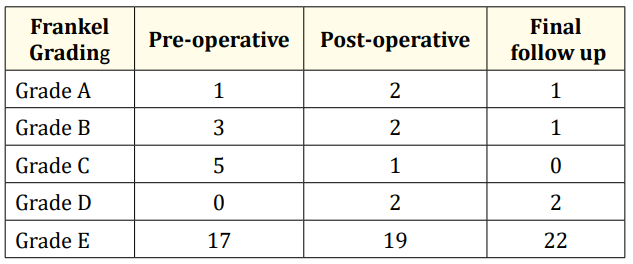

Symptoms at presentation included mechanical back pain, cosmetic deformity of back and neurological symptoms. Neurological deficit was diagnosed pre-operatively in 9 patients [Frankel grade A-1, B-3 and C-5, E-17] [Table 2]. At final follow up, Grade A improved to Grade B in 1 patient, Grade B improved to Grade D in 2 patients and to Grade E in 1 patient, Grade C improved to Grade E in all patients. At the end of 2 years, all patients maintained or improved their neurological examination status except one who developed paraplegia immediately post-surgery and did not recover. 1 patient suffered transient left sided L4 weakness which improved to normal at final follow-up. At total at the end of 2 years, Frankel grades were A-1, B-1, C-0, D-2, E-22 [Table 2].

Table 2: Neurological examination findings: Frankel’s grading.

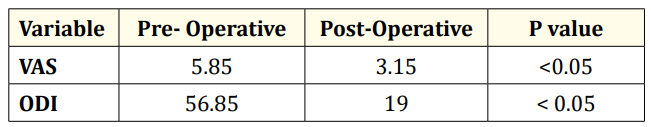

Similarly, significant improvement [P value< 0.05] were noted in pain [VAS] and functional [ODI] scores. The mean pre-op VAS score was 5.85 [SD=1.64, Range=2-8] which improved to 3.15 [SD= 1.29, Range=2-6]. The mean pre-op ODI score was 56.85 [SD= 19, Range= 20-90] which reduced to 19 [SD= 8.24, Range=10-40] at final follow up [Table 3].

Table 3: Clinical outcomes: VAS and ODI.

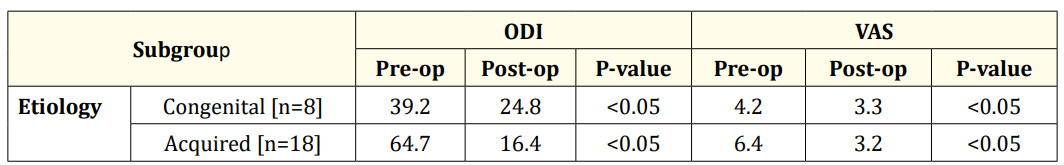

Based on etiological evaluation among congenital and acquired cases, [Table 4] a mean preoperative ODI score of 39.2 for congenital and 64.7 for acquired cases was found. These improved to 24.8 in congenital and 16.4 in acquired etiologies respectively. The VAS scores improved to a mean of 3.3 from a pre-operative of 4.2 in congenital and to 3.2 from 6.4 in acquired etiologies subgroup. ODI and VAS improved better in acquired group paradoxically because of higher pain and disability scores preoperatively as most patients in congenital group presented with deformity whereas in acquired group pain was a common presenting feature.

Table 4: Clinical outcomes and etiology.

Single level osteotomy was performed in all patients. Osteotomies were performed from levels T5 to L3 [Table 5] depending on the apex of kyphosis, most commonly at T12 and L1 levels [14/26]. Osteotomy was done at T10 or above in 6/26 [23.1%] and at T11or below in 20/26 [76.9%] patients [Table 5]. The mean number of levels fused was 5.69 [SD= 0.93, Range=4-8 levels]. The mean operative time was 243.46 minutes [SD= 48.82, Range=180-390 minutes] with mean intra-operative blood loss of 336.92 ml [SD=86.62, Range=200-500ml] [Table 6].

Table 5: Osteotomy levels.

Table 6: Operative outcomes.

The mean pre-operative kyphotic Cobb’s angle was 96.54o with a range of 70-130o [SD=15.73]. After surgery, curves averaged 30.77o [SD= 10.17, Range=20-50o] yielding a significant average correction of 68.57% [P value <0.05]. At final follow up, the mean kyphotic curve was 34.81o [SD= 10.15, Range=20-60o] indicating average final correction of 64.15%. An average loss of 4.23o at final follow up was documented [Table 7].

Table 7: Radiological outcomes.

Similarly, average scoliotic Cobb’s angle improved significantly [p<0.05] from 52.54o [SD= 18.13, Range=26-88°] preoperatively to 15.77 [SD= 5.07, Range=10-26° postoperatively, with average correction of 68.79%. At last follow-up, average scoliosis angle was 19.42o [SD= 5.31, Range= 12-30o] with mean correction of 60.95%. An average loss of correction of 3.66° at final follow-up was noted [Table 7].

The preoperative sagittal vertical axis [SVA] averaged 7.6 cm [SD= 2, Range=3.5–11 cm] and improved significantly [P value <0.05] to 3.94 cm [SD= 0.86, Range=2.5-6 cm] at the end of 2 years. Bony fusion was achieved in all patients. Out of 26 patients, 9 patients exhibited Grade 1 fusion [34.62%], 15 patients Grade 2 fusion [57.70%] and 1 patient Grade 3 fusion [3.85%] as per Bridwell’s criteria of radiological fusion.

[Table 8] Two patients were diagnosed intra-operatively with dural tears and were repaired primarily by suturing the dura followed by water-tight closure of operative wound. One patient had an implant failure [screw back out] which needed revision surgery. One patient developed superficial wound infection which was managed conservatively with antibiotics and regular dressings. One patient [Congenital Kyphoscoliosis, ASO at L3 level] had a new onset neurological deficit of Left side L4 nerve root [Quadriceps weakness 3/5] while in two other patients neurological examination worsened from pre-operative Frankel grade C to A in the immediate post-operative period. One patient developed complete paraplegia [Congenital Kyphoscoliosis, ASO at L1 level] which failed to recover at final follow-up. It was later realised that the osteotomy was incomplete and forced closure with load on implants led to translation within the narrow canal. The changes in neuromonitoring signals were detected during manipulation and closure of osteotomy. On realization of this, the correction maneuver was reversed with adequate ventilation, reduction of inhalational anaesthetics and maintenance of mean arterial pressure. In spite of these precautions, the neuromonitoring signals did not return to baseline levels and amplitudes increased partially by the time closure was complete. The patient was also given short course of iv steroids, but only partial improvement was found in neurological outcome even at final follow up (Frankel Grade D). The same patient suffered from screw pull out (as mentioned above) and failure of construct with loss of correction for which a revision surgery with extension of fixation and redirection of loosened screw was performed. The learning points from this case were that osteotomy should be completed before closure is attempted in order to avoid translation over a hinge. Also forced closure leads to excessive stress on implants which can lead to implant failure and pseudoarthrosis. Intra-operative Neuro-monitoring is an essential tool in the hands of a deformity surgeon as multi-modal monitoring acts to warn when the damage is done and aids in timely corrective measures. In our case timely reversal led to partial recovery which would otherwise have been a complete and irreversible neuro-deficit. Rest all patients improved with conservative management at 3 months follow-up.

Table 8: Complications.

14 years old male patient presented with a progressive deformity of back and no neurological deficit. Patient had a positive sagittal balance with compensatory increased lumbar lordosis. X-rays [Figure 8] revealed block vertebrae D10-D12 resulting in rigid kyphotic deformity of 75 degrees. Patient was operated with an apical osteotomy with correction of sagittal balance. 2 year follow-up radiograph [Figure 9] shows fusion, maintained correction and sagittal balance without any implant related complications.

Figure 8: Pre-operative radiograph.

Figure 9: Post-operative radiograph.

The present study analysed the clinico-radiological efficacy of apical spinal osteotomy [ASO] for severe rigid kyphoscoliosis in paediatric patients. The uniqueness of the study is the rarity of the study group with diverse etiologies and severity of deformity in paediatric population [age group 6-14 years]. These patients were treated with a single level osteotomy at the apex, hence Apical Spinal Osteotomy. Rigid kyphoscoliosis in quite common in young children [2,10,14-16,23,25,29]. The ‘pitched forward’ posture causes back muscles to strain toward successfully or unsuccessfully reducing a patient’s tilt resulting in additional energy expenditure which leads to reduced functional capacity and a poorer quality of life due to mechanical and neurological symptoms [3]. The aim of surgery is to fuse the spine in a balanced position that is as close to normal configuration as possible.

A combined anterior release and fusion followed by posterior spinal fusion and instrumentation was often performed for large and stiff curves [11]. Both open and endoscopic approaches have negatively impacted pulmonary function when compared to posterior only approach [17,20]. Luhmann and Lenke [22] concluded that patients treated with pedicle screw- only instrumentation presented similar results to patients with combined treatment [60.7 vs 58.5%], without negative effects on pulmonary function from anterior release. With the advent of modern instrumentation and pedicle screw system, a single posterior approach is preferable to reduce morbidity to the patients. All patients in the present series were operated with a single posterior only approach.

In highly rigid severe spinal deformities, conventional correction methods such as posterior only or anterior release and posterior instrumentation, are usually unsatisfactory and a more aggressive approach is necessary [26]. Closing wedge osteotomies [CWO] like SPO, PSO and VCR can provide acceptable clinical and radiographic results for patients with sagittal imbalance [4]. Suk., et al. reported on a posterior only approach with a VCR for fixed lumbar spinal deformities [26] as well as for severe rigid scoliosis [25,27]. They reported excellent surgical correction with minimal long term complications. However, anatomic limitation of a vertebral body restricts CWO to about 35o lordosis [5,12,18]. When sagittal imbalance exceeds 25 cm, consideration should be given to performing more than just 1 CWO to obtain adequate correction [6], increasing the risks and complications of the surgery. In our technique, correction of severe rigid deformities was achieved with the help of single level apical osteotomy for all patients. End point of column shortening in our series was direct visualization of dural buckling, any NMEP/SSEP signal change or loss and more than 15 mm of closing of the wedge on convex side at posterior face of osteotomy. Also, if the residual bony defect after closing osteotomy/ column shortening was less than 10mm, autogenous cancellous chip bone was placed. If anterior gap was more than 10mm, titanium mesh cage filled with bone graft was placed. The benefits of performing an apical osteotomy are efficient correction at the very site of rigid deformity, potential to correct deformity in both sagittal and coronal planes, direct bone to bone contact instead of spanning reconstruction giving better fusion rates and less implant related complications.

Chen., et al. [10], Shimode., et al. [23], Bakaloudis., et al. [1], and Wang., et al. [28] rigid kyphoscoliosis with varied etiologies and have documented the efficacy of thoracic PSO, VCR and apical resection procedures with final corrections in the range of 54 to 69%. Mean age of patients in these studies was in the range of 12-34 years. Similarly, Lenke., et al. [19] reported the results of VCR in 35 paediatric patients with a mean follow up of 2 years. The mean age of patients in their series was 11 years [Range 2-18 years]. They performed single [n=20] and multi-level osteotomies and documented overall correction rates of 51-60% with an average blood loss of 691 ml. In our series, the mean age of patients was lower at 9 years [Range 6-14 years] studying the efficacy of single level ASO in paediatric patients with varied etiologies as documented above and correction rates of 64% and 60.9% for kyphotic and scoliotic curves respectively. The average blood loss in our series was 337 ml.

Treatment of severe kyphoscoliosis with osteotomies is associated with significant blood loss. Various studies [7,8,14,23,29] for the treatment of rigid kyphoscoliosis operated with apical lordosating osteotomy [ALO], spinal wedge osteotomy [SWO], multilevel modified VCR amd closing opening wedge osteotomy [COWO] have documented blood loss in the range from 717- 3340 ml. In a multi centric trial in 2013 [21], authors emphasized the magnitude of blood loss possible in VCR. They reported an average blood loss of 1610 ml. Similarly, Sponseller., et al. [24] in their study of children comprising neuro muscular scoliosis operated with VCR reported mean blood loss of 1785ml. Average blood loss in our series was 337 ml [Range=200-500ml] which is much less than the previously described series. We believe that preserving the dural sac within the bony shell until adequate vertebral column resection is performed significantly prevents blood loss from the bleeding epidural veins in our technique. Also in age group < 14 years the tissue planes are well delineated with minimal element of degeneration.

In correction of high magnitude rigid curves, both conventional [SPO, PSO and VCR] and newer unconventional osteotomies [apical resection osteotomy, SWO and COWO] have reported similar correction rates. However, conventional osteotomies may require correction at multiple levels which increases the morbidity of surgery. Bakaloudis., et al. [1] reported correction rates of 65% with PSO in paediatric patients. Chen., et al. [10] documented correction of 69.87% with apical resection osteotomy. In our series, mean kyphotic curve was 96.5o which at final follow up was 35o indicating average final correction of 64.15% which remained consistent at the end of 2 years [Loss of correction=4.2o]. Our results were similar to many studies mentioned in the literature 1,7,10,23,28 thus, proving efficacy of the technique

PSO and VCR have provided good results not only in radiological terms but also in clinical terms in the patients with fixed sagittal imbalance caused by multiple etiologies, however, only a few series have reported functional outcomes. After performing PSO in 27 patients with fixed sagittal imbalance, Bridwell., et al. [6] noted that the ODI improved from 51.21 preoperatively to 35.75 at the last follow-up, and 92.3% of the patients were found satisfied with the treatment on the overall satisfaction score. Kalra., et al. [13] also described the ODI having reduced from the preoperative 56.26 to 11.2 after operating 15 patients with rigid tuberculous kyphosis. In a similar study on 35 patients with fixed sagittal balance, Kim., et al. [16] reported the improvement of the ODI from 49 to 24 and very good satisfaction in 87% of the patients. Corresponding to the aforementioned results, our series did demonstrate a significant decrease in the ODI after surgery (57 to 19) and good functional improvement at the final follow- up.

Bakaloudis., et al. [1] reported 5 medical complications and 1 neurological complications in their series of 12 patients, thus having complication rate of 50%. Similarly, Chang., et al. [8] reported complications in 41 of 83 patients in their series documenting complication rates of around 50%. Kawahara., et al. [14] reported no neurological complications. However, their study was small comprising of only 7 patients. Chen., et al. [10] documented complications in 10 out of 23 patients. Lenke., et al. [19] reported complications in only 4 out of 35 patients in their series of paediatric deformity patients operated with VCR. However, the alarming rate of complications associated with VCR in paediatric patients were noted in a multi centric trial of 147 patients [21]. They noticed complications in 59% patients. Sixty eight patients had a complication during surgery [most common- changes in spinal cord monitoring data and blood loss more than 2 litres] and 43 had a postoperative complication [most common-respiratory related]. No patient in their series had a complete permanent neurological deficit. In our series, patients had a general complication of 15% which included 2 cases of dural tear, one case each of implant failure and superficial infection. One patient had a new onset neurological deficit while in two other patients neurology examination worsened from pre-operative Frankel grade C to A in the immediate post-operative period. One patient developed complete paraplegia which failed to recover at final follow-up, rest all improved with conservative management at 3 months follow-up. Neurologic complication rate stood at 7.6% and overall complication rate was 30.76%.

The major limitation of this study is its retrospective design; however database for this study was constructed without any hypothesis, therefore all data was collected in unbiased manner. Nonetheless we recognize that prospective data collection would have strengthened the salient points of this study. Another limitation of the study is limited number of cases with varied etiology having a relatively short follow-up making the case cohort a nonuniform one managed by single surgical technique. A longer follow up in a larger cohort of similar etiology would help understand the effect of etiology on correction and morbidity with the technique. Longer follow up would definitely bring forth the pitfalls of long segment fusion in pediatric population and effect of residual deformity resulting in mechanical back pain, implant loosening and loss of correction can be evaluated better. The authors have used ODI as an outcome measure though it is not validated in paediatric age group. ODI was used since, there were no other paediatric defined outcome measures documented in a locally available language at the time of data collection of the study. This is a limitation of the study. Moreover all the parameters are answered by parents, so a bias of subjective effect on evaluation cannot be ruled out.

Technique of single level apical spinal osteotomy through a posterior approach for the treatment of severe rigid paediatric kyphoscoliosis has been described. The technique can safely be performed in small children with good clinico-radiological results and satisfactory correction rates. The description indicates that the procedure is technically demanding, but can be reliably executed by any spine surgeon familiar with decompression surgery and instrumentation techniques. It is versatile and safe for correction of rigid kyphoscoliosis in children, the treatment of which to date has proved to be extremely difficult in experienced hands.

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

No funding or material support has been received in any form for this manuscript.

None.

Copyright: © 2019 Sameer Ruparel., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.