Fanello Serge*

Public Health Department, Angers University Hospital; Angers Medical School Angers, France

*Corresponding Author: Fanello Serge, Public Health Department, Angers University Hospital; Angers Medical School Angers, France.

Received: February 22, 2019; Published: March 11, 2019.

Citation: Fanello Serge. “Average 15-Year Follow-Up of 128 Children Admitted in a Child Welfare Center in Maine-et-Loire (Western France) ”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.4 (2019):24-35.

Objective: The aim of our study was to describe the pathways and long term outcome of abused children placed in a Child Welfare Center and to identify factors influencing their outcome.

Method: One hundred and twenty-eight children admitted in a Child Welfare Center of Maine-et-Loire, Western France, were included in a catamnestic survey conducted from September 2011 to June 2013. The study focused on the different children pathways in and out the Center.

Medical, especially mental health, socio-administrative and educational data were recorded.

Results: The admission of the children was due to psychological violence in 65 cases (50.8%), physical violence in 32 cases (25%), severe negligence in 14 cases (11%) and sexual abuse in 2 cases (1.6%). Forty-six percent of the children had at admission a delayed growth rate which was caught up in half of the cases at the end of the study. CGAS score showed a non-significant improvement between admission and end of follow up.

Conclusion: This survey provides the first description of child abuse in the French department of Maine-et-Loire. Children were admitted with a delay between detection and admission. Most of them suffered from physical disabilities and mental disorders. Child abuse is a public health problem often underestimated in France. It can be improved through better detection of children at risk, access to broader educational measures and recourse of trusted adults.

Keywords: Child Abuse; Toxic Parents; Mental Disorders; Early Detection; Aggregate Social Integration Scale; Broad Educational Measures; France

Recent studies in high income level countries have shown that from 4% up to 16% of children were at risk of child abuse, psychological violence and educational deficiencies [1,2]. In the United States, $ 20 billion are spent annually to face this public health problem [3].

In France 297,250 children under 21 years old benefited from a child welfare measure in 2012 [4]. They were placed in different children's institutions or followed by social workers. Delays in detection and placement of abused children may affect their emotional, psychological and educational becoming [1,5]. As early as 1945, Spitz., et al. have described the potential effects of early placement on the emotional deprivation of children [6], although this still remains a debated question [7]. Despite of the high social burden and cost of child abuse, there is little data concerning this issue in France.

The aim of our study was: (1) to describe the pathways and long term outcome of children placed in a child welfare center; (2) to identify factors influencing their outcome.

Our study was commissioned by the Maine-et-Loire local government, Western France. The research was funded by the National Monitoring Centre for At-risk Children (ONED), the French Psychiatric and Mental health foundation and the ‘Fondation de France’.

One hundred and twenty-eight abused children admitted in the Child Welfare Center of Maine-et-Loire, Western France were included in a catamnestic survey conducted from September 2011 to June 2013.

The follow up of the children concerned their different pathways: their stay in the Welfare Center as well as their placement in foster care families.

A survey protocol was set up to record medical, social, administrative and educational data.

The survey was administered by a professional staff including a child psychiatrist, a psychologist and a public health physician of the University of Angers.

One of these professional worked in the vicinity of the children for more than twenty years. Additional data was collected from social workers or foster families.

The recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the French Human Subjects Committee (CCTIRS n°910183) in agreement with the National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties (CNIL-France)-Decision DR-2010-325. In each case, ethics approval was obtained from the family or an entitled person.

The subjects were recruited among children under 4 years old, placed from 1994 to 2001 in the Child Welfare Center of Angers.

A survey protocol was elaborated at the University of Angers.

Evaluation was done at T1 (admission in the Maine-et-Loire Child Welfare center) and T2 (exit from the Child Welfare Center or, for most of them, from foster families).

This evaluation was particularly based on the CGAS scale (Children's Global Assessment Scale) adapted in French by Boyer., et al. [8-12]. This scale was developed to measure the severity of mental disorders among children aged 4 to 16 years old. The CGAS scale assigns a score ranging from 1 to 100 to rate the general functioning of children in various areas (at home, at school and with peers). It consists of several components depending on symptoms and degree of achievement in different psychological, social and academic fields. Scores above 70 are considered to be in the normal range while a score of 50 or lower calls for an intervention [13]. For children under 4 years old, the PIR-GAS scale (Parent Infant Relationship Global Assessment) was used to evaluate relationship between parent and child [14]. Socio-demographic variables included age, sex and parent education.

Our protocol also included information on the causes of children admission as well as the pathways of the children.

Mental disorders were divided in four main groups: mood, behavior, anxiety and other trouble. 15 Parental acceptance of the child placement was evaluated.

An aggregate social integration scale was built to evaluate the social integration of the children. Four favorable prognosis factors were identified: (1) absence of mental disorder; (2) CGAS score higher than 70; (3) good academic achievement; (4) a pathway including less than four foster care placements.

The concept of “toxic parents” refers to parents who do not respect the ability of their child to flourish and find their own way.

They refuse to “recognize” them as they are [16].

Pregnancy denial is defined as “a woman's lack of awareness of being pregnant” [17] “Affective denial” indicates a woman awarded of her pregnancy but behaving at certain times as if she was not pregnant [18].

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (median and interquartile range if the normality assumption could not be verified). Qualitative variables were described by numbers and corresponding percentages.

For univariate analysis, the statistical test used was Pearson's chi-squared test for qualitative variables. For quantitative variables, the homogeneity test was calculated using Fisher's exact t-test for comparison of two groups and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparison of three or more groups. The association between two quantitative variables was estimated by the Pearson correlation coefficient. The significance level was set at 0.05 and all tests were bilateral. Clinical psychological comparisons between the inlet and the outlet of the test called on paired data (Wilcoxon’s test for quantitative variables, McNemar's test for qualitative variables). Data were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 21 IBM Corporation ®1989-2012).

No imputation was performed in case of missing data. Statistical analyses were performed on pre-established analysis design.

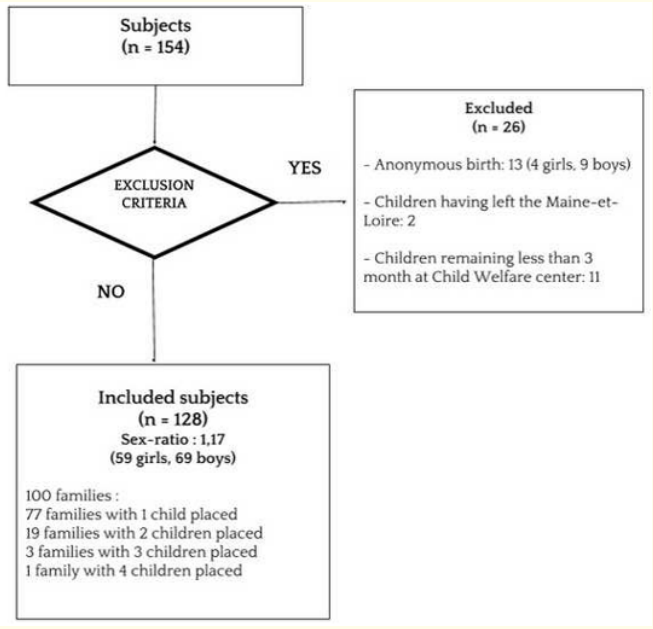

From 1994 to 2001, 154 children under four years old were admitted in a Child welfare center situated in Angers (Maine-etLoire, France). Twenty-six children were excluded for the following reasons: thirteen were born anonymous (childbirth “Under X” according to the French Law) and were waiting for adoption. Eleven had a stay of less than 3 months in the Child Welfare center and two had left the Maine-et-Loire.

One hundred and twenty-eight children were included in our study: 59 girls and 69 boys (Figure 1). Upon admission in the Child Welfare Center, forty-four of them (34.4%) had less than one year, twenty-six (20%) had between one and two years, twentysix (20%) had between two and three years and thirty-two (25%) were over three years old.

These 128 children were issued from 100 families. Seventyseven families had one child placed, 19 families had 2 children placed, 3 families had 3 children placed and one family had 4 children placed.

Figure 1: Flow Chart of the study. Children under four years admitted between 1994-2001 at the Maine-et-Loire child welfare center

Twenty-one children (16%) were premature. The mean birth weight of the children was 3100 g. Thirteen children (10.2%) had a birth-weight of less than 2500g.

The admission of the children was due to psychological violence in 65 cases (50.8%), physical violence in 32 cases (25%), severe negligence in 14 cases (11%) and sexual abuse in 2 cases (1.6%). In 18 cases (4 girls and 14 boys) there was an association of physical and psychological violence. Silverman's syndrome was identified in 7 children (6.5% of cases). Two of them had previously been identified by medical or social services as “at-risk abused babies”. In four cases a Silverman syndrome was diagnosed in another child of the same family.

Out-of-home admission fell under the French Child Protection Act of March the 5th, 2007. It comprised educational neglect (96 cases, 75%), safety condition (79 cases, 61.7%), healthy condition (63 cases, 49.2%), physical, emotional, social or intellectual development (57 cases, 44.5%) and educational neglect (16 cases, 12.5%). Education flaws without maltreatment were involved in 14 cases (10.9%).

For 44 children (34%), admission was due to domestic violence in 15 cases (11.7%), parent’s hospitalization for psychiatric disorders in 11 cases (8.5%), sexual abuse of a sibling (9 cases, 7%), abuse of a sibling in 9 cases (7%).

A mean of 3.9 ± 1.8 children was present per family (with a range of 2 to 11 children). Before admission in the Child Welfare Center, 70 children (55%) lived with their parents. Thirty-eight (29.7%) came from a host structure (foster care, mother-and-child center, trusted person). Ten (7.8%) were newborn and nine (7%) were hospitalized in a Pediatric Ward prior to admission.

Fifty-nine children were brought up by a single parent: mother alone for 55 children in 45 families, father alone for 4 children in 2 families. Fifty-two children issued from 38 families had both parents. Seventeen children had a stepfamily (13 children from 12 families) and 4 from host families. Thirty-two children (25%) were of unknown paternity, five (4%) were motherless children and four (3%) were parentless children.

Affective parental deficiency was noted in 41 cases (32%), mental or physical violence between couples in 70 cases (55%).

Precarious living conditions were reported in 41 cases (32%) with housing problem in 20 cases (15.6%). In 15 cases (11.7%) a parent was imprisoned.

Mental disorders of one of the parents were found in 68 cases (53%), physical disabilities in 20 cases (16%), intellectual disability in 17 cases (13%).

Eight pregnancy denials (6.3%) were found. They were not significantly associated to mother’s mental disorders (52% vs. 54%). An "affective denial" was found in nine cases (7%).

Parents' adhesion to the admittance decisions was poor.

The weight and height of the children was measured at T1 and T2 and available for one hundred and fifteen children. Fifty-three children (46%) showed growth retardation at admission. Thirty of them (57%) recovered growth retardation after an average of 2.5±1.6 years. Figure 2 summarizes growth "catch-up" curves.

![<p>Figure 2: Growth curve of 30/53 subjects having a retarded growth curve on admission.</p>

<p>(Cole,1990 and WHO Growth Charts [39,40]).</p>

<p>3rd and 97th percentiles - - - 25th and 75th percentiles</p>](https://actascientific.com/ASPE/images/IJMCR/ASPE-02-0066-fig2.PNG)

Figure 2: Growth curve of 30/53 subjects having a retarded growth curve on admission.

(Cole,1990 and WHO Growth Charts [39,40]).

3rd and 97th percentiles - - - 25th and 75th percentiles

Table1: Social and family characteristics of the 128 children included at entrance and exit of Child Welfare center. *children being in the child welfare center or in foster families

At the end of the survey (T2), 69 children (54%) were placed in foster families. 39 children (30.5%) returned to their original families and 18 (14%) were entrusted to an institution or a specialized foster care. Two children (1.6%) were assigned to a trusted person.

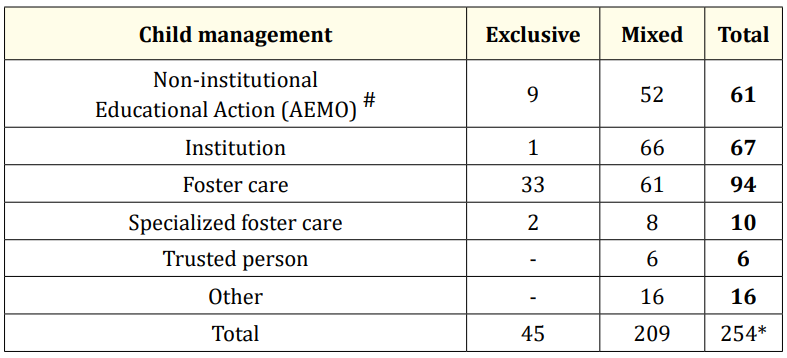

Figure 3 and Table 2 indicate the pathway and trajectory of the children. An average of 4 ± 3.4 placements per child was found with a range from 1 to 20 placements.

Figure 3: Age reached by our cohort.

* Missing data

n = number of children in our cohort at a given age

i.e. 49 children reached 18 years old and 24 were still in the child welfare center

Table 2 : Children’s trajectory.

A child could benefit from several measures at the same time

# Measure intended to keep the child in his natural environment

* An average of 4 out-of-home placement in two different structures/child

Among the 128 children under four years old admitted in the Child Welfare Center, 17 (13%) left the child welfare service before reaching ten years old. Eighty-three children (64.8%) had successive placements in different structures and forty-five children (35.2%) benefited from a single placement. Eighty-four (65.6%) were assigned to a trusted adult.

Among 49 subjects (38% of the cohort) who reached the age of legal majority (18 years old), 24 (49%) required a psychiatric expertise. Eight of them benefited from an adult protection measure (guardianship or trusteeship) and nine received a Disabled Adults’ Allowance.

Three parents had their parental authority abolished. Seven children became state wards and three others were placed under governmental guardianship due to the death of both parents.

There was no significant correlation between PIR-GAS or adapted CGAS scores at admission (T1) and social integration at the end of the follow-up (T2) (p>0.05).

At T1, one hundred and sixteen children suffered from mental disorders. Ninety-eight had still mental disorders at T2 after an average of 14±4.5 years later. Seven children out of 8 without mental disorder at T1 acquired mental disorders at T2. Predominant mental disorders at admission were behavioral and mood disorders (respectively 44 (37.5%) and 30 (25.8%) out of 116 cases). At T2 behavioral and mood disorders concerned respectively 57 and 23 out of 98 cases (Table 3).

Table 3: Evolution of mental disorders from admission (T1) to the end of care (T2)

* In 4 cases, the evaluation was missing

TOTAL mental disorders at T1: 116 cases

TOTAL mental disorders at T2: 98 cases

T1 concerned children at admission in the Maine-et-Loire Child Welfare center.

T2 was evaluated in the Child Welfare Center or, for most of them, in foster families.

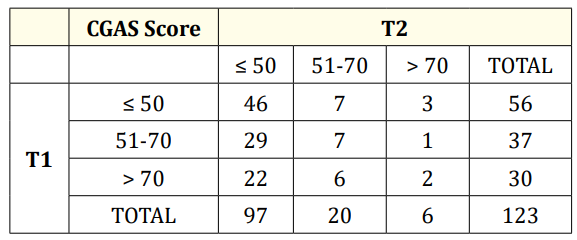

Fifty-two percent of children with a CGAS<50 at T1 benefited from a scale improvement at T2, thought this improvement was not significant. For 11 children (7%), the CGAS scale evolved unfavorably between T1 and T2 (Table 4).

Table 4: CGAS score between T1 and T2.

Out of the hundred and twenty-eight children, ninety-one attended high school, with a complete curriculum in 40 cases (44%) and a partial curriculum in 35 cases (38%). Thirty-eight children (42%) left school without any diploma.

For the remaining 37 children (28.9%) who did not have a regular school attendance, 17 had behavioral disorders, 7 experienced school absenteeism, 6 suffered from physical disability and 7 had mental health problems.

Children who suffered physical or sexual abuse prior to their placement were not affected by more mental disorders than the others (p = 0.37). Physical or sexual abuse was not significantly associated with a change in CGAS score between T1 and T2 (p = 0.21).

The initial CGAS score was significantly lower among children placed in foster care or followed by a trusted adult (CGAS score of 39.5 ± 15 and 39 ± 8 respectively) than those placed in institutions or who were able to return to their original families (CGAS score of 47 ± 8 and 42 ± 13 respectively, p < 0.01).

Children (n = 25) having a low CGAS score (32 ± 13) at T1 were more likely to develop mental disorders at T2 (p <10-3).

Ninety-six (77%) young adults had persistent mental disorders after leaving the Child Welfare Center with a CGAS score under 70. Fifty-one (40%) had a chaotic social course with iterative admittance in different social institutions.

An Aggregate Social Integration Scale was built on the basis of the four favorable prognosis factors: (1) absence of mental disorder; (2) CGAS score higher than 70; (3) good academic achievement; (4) satisfactory pathway with less than four foster care placements.

After leaving institutional care, presence of three or four positive criteria proved to be favorable prognosis whereas one or two criteria indicated poor social and professional integration.

Sixty-nine children (54%) in our cohort had a good prognosis whereas fifty-nine (46%) had not. That was particularly true for 17 of them (13%) who had only a single positive criterion.

Nine out of ten children with one or two criteria were unable to achieve social integration (p < 0.006).

Delay between identification of a risk and admission in the Child Welfare Center of the children was an essential condition of success. A delay greater than 15.4 ± 14 months was a cause of failure, whereas a delay inferior to 10.3 ± 11.9 months enabled a favorable issue (p = 0.03).

This survey provides the first description of child abuse in the French department of Maine-et-Loire.

On November 20th, 1959, France signed of the United Nations’ Declaration of Children's Rights.

The French Child Protection system is ruled by three essential Acts:

The French Child Protection system is managed by Child Welfare Authorities under the control a special judge for children. Most of children are placed after court orders in foster families.

Child Welfare Centers host children requiring long-term placement. They are ruled by social educators allowing the children to benefit from a family-life style environment. The children are placed under court order by the children's judge (February 2, 1945 Act) [20].

The children came from “toxic” families with psychological and physical violence and there was a delay in the admission at the Child Welfare Center. Most of them suffered from mental disorders.

There was a significant improvement of children suffering from growth retardation. However no significant improvement was found regarding the CGAS-scale.

In France in 2005, Chardon., et al. [21]. found 17.5% of single mother families and 15% of single fathers. In our cohort, there was 45% of single mothers and 2% of single fathers.

Our survey revealed a pregnancy denial rate of 62.5 per 1,000 births. In comparison, Pierronne., et al. found in 2001 a pregnancy denial rate of 3.7 ± 0.84 per 1,000 births in the French general population [22].

The correlation between pregnancy denial and mental disorders was present in 50% of the cases, in our survey compared to 20% in a study by Chaulet., et al. concerning 75 mothers in a French University Hospital [23].

“Our survey provides the first description of child abuse in the French department of Maine-et-Loire. Child abuse is a serious public health problem often underestimated in France. It can be improved through better detection of children at risk, access to broader educational measures and recourse to trusted adults ».

There were 17% of premature births and 43% of newborn with a birth weight of less than 3,000 g compared to 7% of premature births and 28% of newborns in the French general population [24]. The proportion of low birth weight (less than 2,500 g) was 10% in our study against 7% in 2003 in the French general population.

In our study, no statistically significant relation was observed in children having a low birth weight and mental disorders either at T1 or at T2. This contrasts with a longitudinal study by Nomura., et al. [25]. conducted in the general population which found a significant increase of disorders such as depression (RR = 10) or social inadequacy (RR = 9) in children having a low birth weight and suffering from maltreatment in childhood.

A significant proportion of children had mental disorders at T1 and T2 (90% and 72% respectively). Comparatively, the prevalence of mental disorders among children in the French general population was estimated only to 12.4% in a study conducted in 1994 [26]. International studies on mental disorders in foster children showed a percentage of mental disorders ranking from 45 to 60% [27-29]. Most of children admitted at the Child Welfare Center were babies (mean age of admission of 1.4 ± 1.25) with proven risk of abuse or maltreatment. Parental opposition to admission decision reflects a dramatic situation which partially explains our data. Children who suffered from physical or sexual abuse prior of their admission did not present more psychiatric disorders than the others.

The prevalence of mental disorders at T2 was higher than that reported by others authors [30,31]. In a French study, Bronsard found 28% of anxiety disorders against less than 5% in our study [35]. The dramatic condition of the children at admission in our study explains this discrepancy. It is also due to our method of investigation, close to casuistry. This is consistent with the high proportion of social adjustment disorders found among children attaining 18 years old: 17 out of 49 subjects were placed under guardianship or were hospitalized for mental disorders.

The pathway length-time spent by the children in the Child Welfare Center – or in another institution (foster families, trusted persons) – is difficult to evaluate in France [33]. In our cohort, half of the adolescents did not reach eighteen years old at the end of the study. The mean age of adolescents at discharge was 16.77 ± 2.2 years. The number of children who benefited from a safeguard release before 18 years old was thus underestimated. Two thirds of children in our study were placed under the responsibility of a trusted adult.

Sixty-four percent of children under the age of 15 repeated school years. This is higher than the average percentage of school years repetition in France which amounts to 39.5% and is one of the highest in the OECD countries [34].

According to Coohey., et al. poor performance in literacy and numeracy tests are correlated with severity and chronicity of child abuse [35].

Selection bias was limited by inclusion of all the children admitted in the Child Welfare Center from 1994 to 2001. We chose to exclude children with anonymous birth in order to avoid missing data on the origin of the family. We also excluded children having a stay of less than three months in the Child Welfare Center as well as children having left the Maine-et-Loire department.

Misclassification was avoided by the fact that all children pathways were analysed by a team comprising the same clinical psychologist, child psychiatrist and epidemiologist.

An adapted CGAS scale was used for children under 3 years old to avoid the poor inter-rater reliability of the PIR-GAS scale [13]. A correlation coefficient of 71% was found between the PIR-GAS scale and our adapted CGAS scale. McNemar’s test showed no significant difference in distribution between the PIR-GAS and the adapted CGAS scale (p > 0.4).

Child abuse is a public health problem in Western France because it is at the root of a high proportion of mental disorders and of social integration difficulties.

This problem can be improved by a better detection of children at risk of abuse and by a shorter delay between detection and admission. Three-quarters of children had a sibling already detected by the child protective service. They could have been admitted earlier if further social investigation had been carried out in the vicinity of the child.

The schooling of the children in our study was in general chaotic. Broader educational measures could improve the social integration of the children. These measures will be cost effective at long term.

Trusted adults can counteract the influence of toxic families as shown by two studies [36,37].

They provide mentorship, stability and direction to young adults and should be more largely used.

Prospective researches, including socio-economic aspects, are needed to evaluate long term evolution at adulthood. The perception of their well-being by the children should also be evaluated. A recent study highlights the need for young people to master their existence [38].

Our survey provides the first description of child abuse in the French department of Maine et Loire which has a population of 148,000 inhabitants.

It pleads for an improvement of the French Child protection Policy.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this study.

This study was funded by the National Monitoring Centre for At-risk Children (ONED), the French Psychiatric and Mental health foundation, the ‘Fondation de France’ and Maine-et-Loire local Government’ family allowances fund.

Copyright: © 2019 Sangita D Kamath., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.