Sunita Singh1*, Jiledar Rawat1, Ashish wakhlu1, Anand Pandey1, Shiv Narayan Kureel1 and Manoj Kumar2

1 Department of Pediatric Surgery, King George’s Medical College, Lucknow, India

2 Department of Radio-Diagnosis, King George’s Medical College, Lucknow, India

*Corresponding Author: Sunita Singh, Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Tatibandh, Raipur, India.

Received: November 22, 2018;; Published: January 29, 2019

Citation: Sunita Singh., et al. “Comparison of Postoperative Clinico-Radiological (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Outcome in Posterior Sagittal Anorectoplasty vs Laparoscopic Assisted Anorectal Pull Through for High/Intermediate-Type Male Anorectal Malformation”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 2.2 (2019):30-36.

Background: The study was done for comparative evaluation of posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) and laparoscopic-assisted anorectal pull through (LAARPT) with special emphasis on anatomical assessment of striated muscle complex (SMC) by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in male anorectal malformation having recto bulbar or rectoprostatic fistula.

Methods: From September 2006 to September 2013 prospective study was done on the basis of semiquantitatively scoring (difference of bulk of striated muscle complex at coronal and sagittal plain in MRI) and functional scoring (fecal continence evaluation questionnaire) in 24 PSARP and 12 LAARPT patients. After 3 yrs of surgery, fecal continence score > 12 was considered as good, 10 to 8 as fair and < 8 as poor.

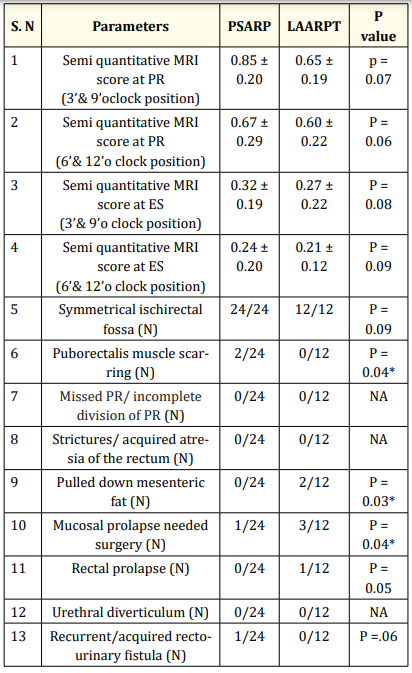

Results: The semiquantative MRI scores at 3’ and 9’o clock and 6’ and 12’o clock in both groups were comparable at puborectalis and external sphincter level. Scarred puborectalis was found in PSARP, while mucosal prolapse and pulled mesenteric fat were found in LAARPT. At the median 3.5 years of follow up (ranged 3.0-5.0 years), 20/24, 3/24, 1/24 and 11/16, 1/16, 0/16 number of patients in PSARP and LAARPT groups had good, fair, and poor fecal continence respectively (p = 0.9).

Conclusion: Anatomically accurate placement of neorectum within SMC is feasible with both the procedures. But mucosal prolapse and pulled mesorectal fat was slightly higher in LAARPT. The level of rectal pouch, semiquantitative/quantitative assessment of SMC and uniform fecal continence scoring are must in all these studies to comment upon the superiority of the procedure.

Keywords: Anorectal Malformation; Fecal Continence, Posterior Sagittal Anorectoplasty; Laparoscopic-Assisted Anorectal Pull

Through; Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Striated Muscle Complex

The Incidence of Anorectal malformation (ARM) is 1 in 3500 to 5000 live births [1]. The posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) is the gold standard treatment for ARM [2]. However, with the introduced of laparoscopic-assisted anorectal pull through (LAARPT), there is a debate on the superiority of procedure [3,4-11]. PSARP allows direct exposure of the anorectal striated muscle complex (SMC) through a posterior midline incision, while LAARPT can position the neorectum accurately inside the SMC without dividing any muscles, thus avoids weakening of external sphincter and perirectal scarring [3,4].

This study was aimed to assess the comparative evaluation of both the procedures in rectobulbar and rectoprostatic fistula. The anatomical assessment was done by postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and, functional assessment by fecal continence evaluation questionnaire, as midterm outcome.

The prospective study was conducted at the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the University hospital from September 2006 to September 2013. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee. We excluded all low ARM patients, recto-vesical fis-

tula cases, primary PSARP or LAARPT, outside operated ARM, redo cases in which previous surgery had lead to extensive scarring, sacral ratio index was < 0.5, spinal dysraphism/tethered cord, female ARM, congenital pouch colon and in whom other surgical procedures performed on anus/rectum/colon. We also excluded patients in whom final continence couldn’t be assessed (i.e. patients having continent catheterization channel and in whom follow up of at least three years couldn’t obtained). All patients having rectoprostatic or rectobulbar fistula were selected for the procedure (PSARP or LAARPT) according to the surgeons’ preference. MRI pelvis and follow up fecal continence evaluation were obtained in 24 PSARP and 12 LAARPT patients. The procedures were explained to the parents and informed written consent was taken from them. To nullify the affect of timing of surgery on the final fecal continence, the age of surgery in both groups was matched (4 to 6 months). Detailed clinico-radiological examination of all patients was done.

The PSARP was performed according to the technique described by de Vries and Pena’s, except in patients having long common rectourinary wall (rectal mobilization done before separating the rectourinary fistula). LAARPT was performed with slight modification of Georgeson’s technique. After identification of limits of SMC by transcutaneous muscle stimulator; limited perineal dissection was done with mosquito artery forceps at proposed anal dimple, strictly in midline.

The MRI pelvis was performed using sigma exide 1.5 Tesla scanner (GEMSOW USA, France) within high resolution phased-array coils (extremity coils). The children wesre sedated by oral trichlorophos or intravenous ketamine. A Foley catheter was advanced into the rectum with balloon inflated to facilitate identification of the rectal lumen. The imaging protocol included T1 and fast or turbo spin T2- weighted sequence in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes at 3-5 mm thickness parallel to the pubococcygeal line. For T1 and T2weighted images time of echo (TE) and repetition time (RT) was (30; 480) and (100; 3600) respectively. To highlight the low-signal intensity muscle and bowel wall against the higher-signal intensity fat and mucosa, fat saturation was also used. Coronal T2-weighted images angulated in line with the anal canal, clarified the sphincter-bowel action. T2- weighted images with fat suppression were helpful for differentiating associated anomalies of the genitourinary tract and complications of surgery. Post contrast fat saturation images are acquired to detect collection, active inflammation. Interposition of mesenteric fat in SMC was identified on T2-weighted sagittal and axial images.

Superficial transverse perineal muscle defines the dorsal border of urogenital diaphragm, which is narrow strip of muscle. Superficial transverse perineal muscle runs more or less transversely across the superficial perineal space anterior to anus and attached to the medial and anterior aspect of ischial tuberosity [12]. When anal canal/pulled rectum is located ventral to the superficial transverse perineal muscle, it was defined as ectopically placed anus [13].

MRI sections were taken in parallel to PC line instead of strictly axial plane. In these sections, the section corresponding to I line (line drawn parallel to PC line at I point), was chosen to identify fibers of Puborectalis (PR). In other words, hypointense fibers of SMC at I line on T2 weighted images were identified as PR [2]. The SMC was best identified on axial images at the level of pubic sympysis and below. The SMC appear hypointense on T2 images while anorectal mucosa is hyperintense. PR is thick muscular sling wrap around anorectal junction [2,12]. Anteriorly some fibers of PR decussate into superficial transverse perineal muscles. PR surrounds the anal canal and the prostate [13,14]. Scarring of levator ani muscle and PR were identified on coronal sections T1-weighted images, where it appeared hypointense [13].

All MRI were reviewed by a single radiologist, who was blind of the procedure. He reviewed the thickness of SMC in the plane corresponding to I line, (uppermost part of SMC identified as PR muscle) and at the level of external sphincter (ES) [6].

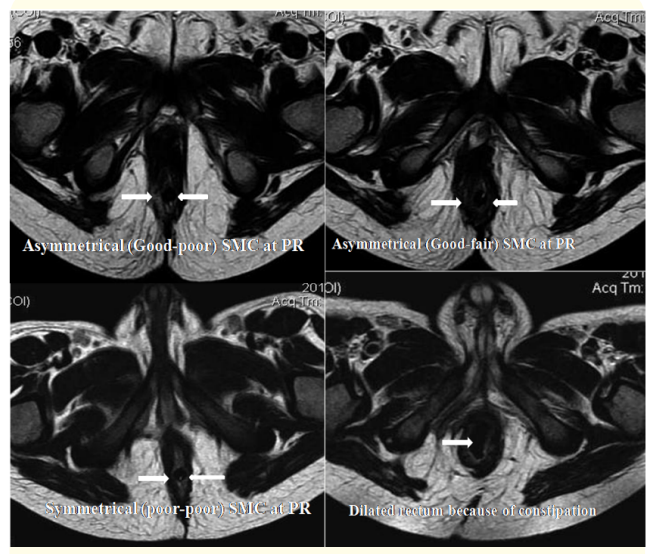

The grading of SMC in axial sections was done as good, fair, and poor, if it was well obvious, thin, and virtually invisible. On the basis of difference of bulk of SMC at 3’; 9’o clock and 6’; 12’o clock position the symmetrical positioning of neorectum within SMC were scored semi quantitatively as shown in table 1 (Figure 1). Asymmetry of ischiorectal fossa predicts the gross rectal malpositioning. Simultaneously associated anomalies and complications of surgery were also assessed.

Evaluation of fecal continence in both groups was done for minimal of 3 years after colostomy closure. The patients were followed up at outdoors visits, by call on telephone, and mail. The evaluation was done by structured self made continence evaluation questionnaire (CEQ), (Table 2) and digital rectal examination by a single experienced surgeon at 6 months interval.

Table 1: Continence Evaluation Questionnaire (CEQ).

Figure 1: MRI sections at I line at 3’ and 9’ o clock position at PR (c) Scoring 2 because of asymetrical (good-poor) SMC; (a) scoring 1 because of asymmetrical (good-fair) SMC, (b) scoring 0 because of symmetrical (poor-poor) SMC, 1(d) dilated rectum because of constipation after LAARPT.

Table 2: Comparison of different parameters between PSARP and LAARPT. LAARPT: Laparoscopic anorectal pull through, PSARP: Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty, NA: Not applicable, TLC: Total leucocyte count, N: Number of patients* p value significant

The data were analyzed by SPSS 17.0 version for Windows. The continuous data was expressed as median (range)/mean with standard deviation (SD) and categorical data as proportions. Comparison of continuous data was done using Student t-test. Chi square test was used for comparison of categorical variables. p value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Over period of 5 years 120 patients having rectoprostatic and rectobulbar fistula were operated. Of these 72.3% (87/120) were from rural area. Regarding fecal CEQ, the response rate of parents was only 33.33% (40/120). Thus 40 patients were included in the study. Two senior surgeons having an experience of about 15 years performed PSARP in 24 patient; while one surgeons having an experience of about 5 years in LAARPT operated 12 patients. MRI pelvis and follow-up fecal CEQ was obtained the mean age of surgery for PSARP and LAARPT was 5.89 ± 0.67 and 4.5 ± 0.23 months (ranged 3 to 18 months, p = 0.07). Rectoprostatic and rectobulbar fistula were found in 14, 10 and 8, 4 in PSARP and LAARPT patients respectively.

As regard to intraoperative or postoperative parameters, there was not much difference between PSARP and LAARPT, except early resumption of enteral nutrition and superficial wound infection in former and higher mucosal prolapse in latter (Table 3).

Table 3: Comparison of MRI findings between PSARP and LAARPT Groups. ES: External sphincters, PR: puborectalis, LAARPT: Laparoscopic anorectal pull through, PSARP: Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty, N: number of patients NA: not applicable, * p value significant

MRI showed scarring of PR in PSARP group, and mucosal prolapse, pulled mesenteric fat in LAARPT group (Figure 2 and 3; Table 4). In both groups, semi quantitative MRI scores at the level of PR were higher than ES. The acquired rectourinary fistula occurred in PSARP group was managed by suprapubic cystostomy and redoPSARP. Tension rectocutaneous anastomosis and superficial wound infection in PSARP were managed conservatively. The patients with pulled mesorectal fat are on conservative management, and further management will be undertaken if there is no improvement in continence in coming 3 years. Four patients having mucosal prolapse in LAARPT group needed revision anoplasty.

Figure 2: MRI saggital section showing (a) mucosal prolapse needed revision anoplasty; 2 (b) Rectal prolapse after LAARPT; 2(c) Pulled mesorectal fat in LAARPT; 2 (d) Fat suppressed T2 weighted images showing acquired rectourinary fistula (right vertical arrow) and leakage of urine through wound after PSARP (left vertical arrow).

Figure 3: (a) Minimal mucosal prolapsed (not needed surgery); (b) mucosal prolapse needed surgery

Table 4: The mean continence evaluation questionnaire scores for fecal continence at 6 months interval. CEQ: Continence Evaluation Questionnaire, LAARPT: Laparoscopic anorectal pull through, PSARP: Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty

At the median 3.5 years of follow up (ranged 3 to 5.0 years), 20/24, 3/24, 1/24 and 11/16, 1/16, 0/16 no patients in PSARP and LAARPT groups had good, fair, and poor level of fecal continence. Table 5 shows that there was no significant difference in fecal continence gained between both groups (table 4). The satisfaction regarding cosmetic perineal appearance was higher in patients of LAARPT.

The PSARP and LAARPT procedures have their own advantages and disadvantages. The opponents of PSARP propose that there is considerable damage to sphincter muscles as well as tiny nerves that maintains anorectal sensation and motility as a consequence of the large sagittal incision [15-18]. The PSARP may have a higher rate of repair dehiscence, subsequent anal stricture, wound infection, and scarring of perineum [6]. Infection and scarring were also noticed by us in PSARP. The LAARPT is advantageous because of less bleeding and minimal mesorectal dissection (less injury to nerves around PR), thus earlier appearance of recto anal relaxation reflux, which indicate earlier control of continence [18]. However, this has not been substantiated by others [2,19].

The anal sphincter can be assessed anatomically by endorectal ultrasonography, computed tomography, or MRI; while functionally by electromanometery and electromyography [2,15,16]. We preferred MRI due to its high sensitivity to detect urethral complication, residual/acquired rectourinary fistula and high resolution images of the soft tissue [6,16,17]. The only disadvantage of MRI is long time for screening, need to sedate the child, availability and subjective factors influencing the interpretation of MRI images [6,20]. To combat subjective factor, all MRI were interpreted by the single blinded radiologist.

As per Tsuji., et al. study, if the thickness of SMC on one side is greater than twice on the other side, the rectum is judged to be mispositioned in relation to the SMC [15]. We, however, compared the muscle thickness for symmetry rather than actual thickness [6]. Because the approach is cranially in PSARP and caudally in LAARPT, so we have done scoring at PR as well as at ES level. In our study, the semiquantitative MRI scores at the level of PR are more than at level of ES (indicating relatively more asymmetry than at the ES). The probable reason was direct identification of SMC at ES via transcutaneous muscle stimulator in both groups. The MRI scores at 3’ and 9’o clock in PSARP and LAARPT groups (0.65 ± 0.11; 0.62 ± 0.02) in this study are slightly lower than Ichijo., et al. (0.75 ± 0.50; 0.77 ± 0.83) [6]. However, Ichijo., et al. operated at the age far older (8-9 months) than us [6].

Regarding duration of surgery, postoperative fever, urethral catheterization and hospital stay both the procedures were comparable to others [6]. The enteral nutrition in PSARP group was started approximately 6 hours after surgery under general anesthesia, however, in LAARPT, as the peritoneum was entered and minimal bowel handling was performed, enteral nutrition was started after 24 hour of surgery. However, some authors resume enteral nutrition earlier in LAARPT.

Technically, more incidence of mucosal prolapse in LAARPT group can be explained by inability to hitch the rectum to the perirectal tissue and pulled mesorectal fat may prevent the anchoring action of the rectum to the surrounding. On other hand, in PSARP, a large raw wound creates a postoperative inflammatory reaction around pulled rectum, which on organization, adheres the rectum to the surroundings, thus preventing prolapse. Our results regarding rate of mucosal prolapse (higher in LAARPT group) were different from others [2,4,6-8,10]. Probable explanation is that, Kimura., et al. had studied on high ARM, in contrast to significant rectobulbar fistula in our study (need more rectal pouch preparation and dissection which affects final fecal continence) [2]. Contrary to Yang and Kudou., et al, where all cases responded on warm hyperosmolar saline in hip bath; we needed more revision anoplasty [4,7]. The author suggest that to make all these type of studies comparable, bulk of SMC, type of ARM and age at surgery should be elaborated in all this kind of future studies.

The CEQ used by us was simulating the questionnaire used by Ichijo., et al, as we agree with their opinion that additional points (requirement for medication, perineal excoriation, and anal shape) provide a complete scenario for the determination of bowel control (as the presence of anal irritation/stimulation, can also affect the bowel control) [6]. In accordance with Yang., et al. we noticed that initial mean CEQ is slightly higher in LAARPT group, but at the end of 3 years, both had no significant difference. It was in contrast to Ichijo and Wong., et al. where better continence was reported in LAARPT [4-6]. The probable explanation for the difference is high proportion of the pulled mesorectal fat in our study, which was not mentioned in any of the above series [4-11]. Other probable reasons may be parents’ negligence towards strict adherence to the postoperative bowel management program, as the study population included a high proportion of illiterate ones (response rate was only 33.3%).

Anatomically accurate placement of neorectum within SMC is feasible in both the PSARP and LAARPT procedures. The only advantage of PSARP is the awareness of technique by junior pediatric surgeons. The advantages of LAARPT are better cosmetic appearance of perineum and relatively less risk of wound infection. The disadvantages of LAARPT are availability of facilities, relatively long learning curve, and slight higher rate of mucosal prolapse. Further, to know the superiority of the procedure, there is still need of studies having matched groups for level of rectal pouch, age of surgery, details of SMC, uniform fecal continence scoring covering all aspects of defecation physiology, and parents’ education regarding postoperative bowel management program.

Copyright: © 2019 Sunita Singh., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.