Doaa Mohammed Youssef1*, Mohammed Hassan Mohammed1, Eman Mohammed EL-Behaidy2 and Asmaa EL-Sayed Abo-warda1

1

Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

2 Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

*Corresponding Author: Doaa Mohammed Youssef, Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt.

Received: September 12, 2018;; Published: October 31, 2018

Citation: Doaa Mohammed Youssef., et al. “Frequency of Cytomegalovirus Infection in Children with Nephrotic Syndrome”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 1.4 (2018): 40-44.

Introduction and Aim: Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS) are the most common type of this disease during childhood. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome (MCNS) is the most common histopathological lesion (80 - 90%) of INS in children and about 90% of patients are steroid responsive, while Congenital nephrotic syndrome is disorder that may be caused by several diseases. Intrauterine infections, especially CMV infection, have frequently been incriminated as etiological factors of secondary CNS. The aim of this research was to evaluate the frequency of CMV infection children with active nephrotic syndrome in our pediatric nephrology unit.

Patients and Methods: This descriptive (cross sectional) study was conducted in pediatric nephrology unit, Zagazig University Hospitals and included 60 patients WITH NS in activity; Participants were subjected to, Full history taking, Clinical examination; general and local, Routine laboratory investigations and Serum samples were tested for HCMV specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) using ELISA Kit, Statistics were done using SPSS version 24.

Results: We found 100% of cases were IgG positive and 7/60 cases were IgM positive, There were no statistically significant differences between IgM positive-patients vs IgM-negative patients according to age, sex and first attack or relapsed NS, There were statistically significant differences between IgM positive-patients vs IgM-negative patients in blood laboratory data in decreases in HB (P = 0.024) and serum urea nitrogen (P = 0.04).

Conclusion: We concluded that zero frequency of cytomegalovirus infection in pediatric nephrology unit, Zagazig university hospitals during follow-up was 12% for cmv IgM and 100% for cmv IgG at ns children patients.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus; Infection; Nephrotic Syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome is characterized by heavy proteinuria, (> 40 mg/m2 /hr), hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin < 2.5 g/dl), hyperlipidemia (serum cholesterol >200 mg/dl) and edema [1]. Human CMV is a virus that infects most of the human population at some stage in their lives, officially named as human herpesvirus type 5 (HHV - 5). It is a member of the Herpes viridae family, subfamily Beta Herpesviridae of viruses, which includes herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2, Varicella Zoster Virus (HHV-3), Epstein-Barr virus (HHV-4), Roseolovirus (HHV - 6 and HHV - 7), and Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus (HHV-8) [2]. Infection with CMV is generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent people, although clinical symptoms of primary infection can include flulike symptoms, or occasionally persistent fever. Laboratory tests may show elevated lymphocyte counts and/or elevated liver transaminase levels [3]. Detection of CMV specific IgM in neonatal serum may also disclose congenital infection. IgM antibodies are only present in 20-70% of infected new-born serum [4] so, detection of CMV in a new-born older than 2-3 weeks could be the result of intrapartum or breast milk acquired infection [5]. Consequently, virological and serological tests will no longer distinguish congenital from postnatal CMV infection. So, diagnostic testing must occur within first 3-4 weeks of life, and earlier testing is best if available [6]. The role of viral infection as a trigger for onset or relapse of INS has been previously suggested. One prospective study has investigated the association of viral infection and relapses of INS, showing that 70% of relapses were preceded by viral infection. Serology and viral cultures allowed identification of respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, parainfluenza, varicella zoster, cytomegalovirus and adenovirus as potential triggers of the relapses (6). In actuality, γ-herpesvirus (EBV), and also β-herpesviruses (cytomegalovirus and herpesvirus 6), can build up latency in immune cells, primarily in B cells [7].

The aim of this research was to evaluate the frequency of CMV infection children with active nephrotic syndrome in our pediatric nephrology unit.

This descriptive (cross sectional) study was conducted in pediatric nephrology unit, Zagazig University Hospitals and included 60 patients in the period from January 2017 until June 2017.

60 children diagnosed as having nephrotic syndrome admitted by activity of the disease (54 cases Primary, 2 cases Secondary and 4 cases Congenital) by inclusion criteria (massive proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and high cholesterol), out of 54 children with PNS recruited for the study; 47 children were steroid sensitive (SS) and 7 were non-steroid sensitive (non-SS), 47 children were relapsed, 7 children were first attack of NS.

Participants were subjected to; Full history taking (age, gender, consanguinity, family history of renal diseases). Medical records of the patients were reviewed for duration of illness and type of NS, response to the treatment, relapses, Clinical examination; general and local, Routine laboratory investigations including renal function (S. creatinine, S. urea), urine analysis (U. albumin, U. sugar, U.RBCs and U. pus), Liver function (serum albumin, ALT and AST) complete blood picture (WBCS, S. Hb and Platletes), CRP and serum electrolytes (Na, K, Ca, and Ph) were done for NS patients.

Serum samples were tested for HCMV specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) using HCMV IgG and IgM. ELISA Kit Bio Cheek, Ine (323 Vintage Park Drive Foster City, CA 94404).

Data were analyzed by Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS), software version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., 2016). Continuous data were presented as Mean ± SD if normally distributed or Median (Range) if not normally distributed. Categorical data were presented by the frequency and percentage. Normality was checked by Shapiro-Wilk test.

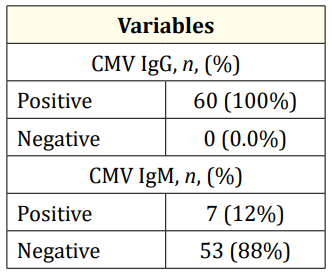

We found that according to etiology of relapse we found 30 children were upper respiratory tract infection, 11 children were Urinary tract infection, 2 children were Gastroenteritis and 4 children had no precipitating factors. Out of 2 children with secondary NS recruited for the study we found one case occurred because of systemic lupus erythromatosis and the 2nd case was post glomerulonephritis due to infection with cytomegalovirus. Out of 4 children with CNS recruited for the study, only1 case was Finnish type and the other 3cases the biopsy was not done. Our cases with age range between 2 months and 15 years with a mean age ± SD of 75.1 ± 50.4 months (39 males, 21 females), were tested for Cytomegalovirus IgM and IgG at time of administration. In our study we found that 7 of nephrotic syndrome children cases were CMV IgM +ve, 53 were CMV IgM -ve and all 60 screened children were CMV IgG +ve table 1.

Table 1: Serofrequency of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) (IgG and IgM) of the studied children.

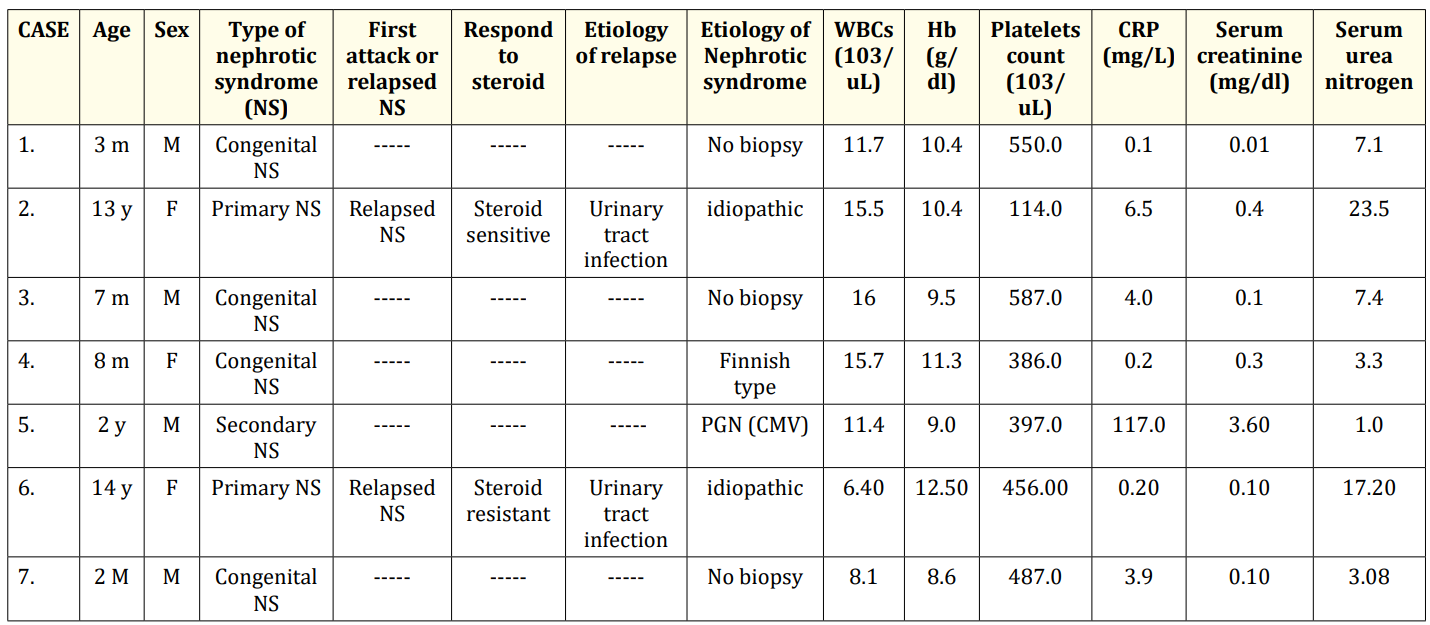

Characteristics of the 7 of CMV IgM positive cases are presented in table 2.

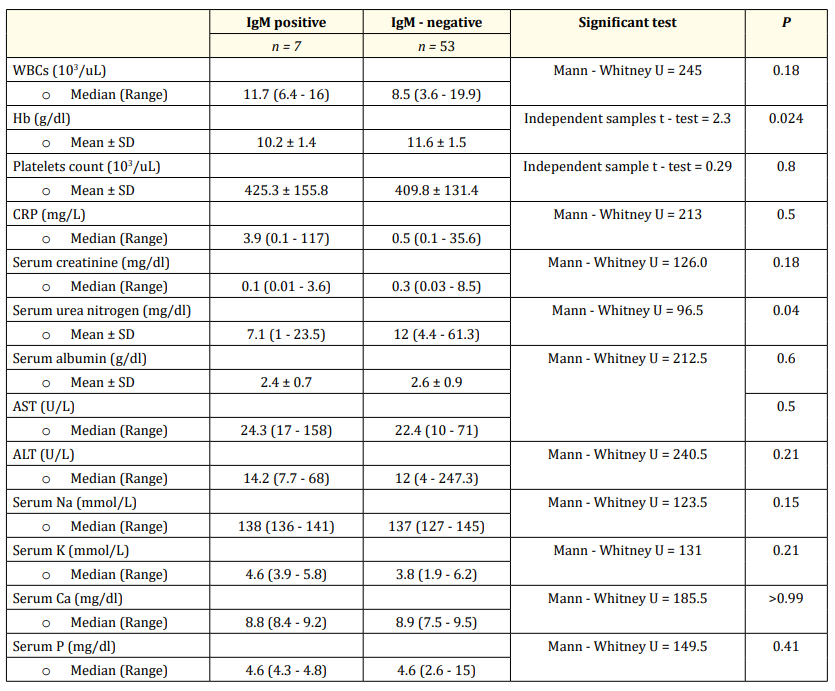

This table 3 showed non-statistically significant differences in all blood laboratory data as regard IgM positive-patients vs IgM-negative patients (P > 0.05). However, there were statistically significant decreases in Haemoglobin (P = 0.024) and serum urea nitrogen (P = 0.04) in IgM positive-patients compared to IgM-negative patients.

As regard correlations between laboratory data and CMV IgG and IgM antibodies in the studied patients; Regarding to CMV IgG antibodies, no significant correlations were noticed., While CMV IgM antibodies showed no significant correlations except a significant negative but a weak correlation was found between IgM and haemoglobin, there was a significant positive but weak correlations were found between IgM antibodies and ALT, AST and serum K levels (data not presented).

Table 2: Baseline characteristics of IgM positive patients.

Table 3: Blood laboratory data of IgM positive - patients vs IgM - negative patients.

Infection is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in nephrotic children. Patients with SSNS have increased susceptibility to bacterial infections and various infections may result in relapses or steroid resistance or may trigger the onset of disease [8].

CMV infection is also reported as a possible etiological factor in congenital, infantile, and adult NS. NS may represent another manifestation of CMV disease although the relationship between CMV infection and glomerular disease is still unclear, Also INS may develop during the course of CMV infection [9].

CMV infections are known to be very common and may be asymptomatic or cause nonspecific febrile symptoms. Less frequently, they may involve the kidneys and even cause nephrotic syndrome [10].

In our patients, the marked increase in serum CMV IgM suggested a possible viral infection, so virus might be involved in the mechanisms of NS. Here, we investigate the link between CMV infect ion and NS in children.

In this study we found that 7 (12%) of nephrotic syndrome children cases were CMV IgM +ve, 53 (88%) were CMV IgM -ve and all 60 screened children were CMV IgG +ve (100%), This is in agreement with [11] who investigated Serological markers of viral, syphilitic and toxoplasmic infection in children and teenagers with nephrotic syndrome.

There were non-significant differences between IgM positivepatients vs IgM-negative patients regarding age, sex and first attack or relapsed NS patients (p > 0.05); This is in agreement with [11], in their study they found. (3 cases relapsed from the 7 nephrotic children cases with cmv IgM + ve) and 103 (60.9%) out of the 169 nephrotic children were male but disagree regarding to age as they found the median age on the first visit was 44 months this can be explained by the different geographical distribution of viral infections worldwide.

Current study showed highly statistically significant differences in characteristics of IgM positive-patients vs IgM-negative patients according to type of nephrotic; This also come in agreement with [12] who studied Congenital and Infantile Nephrotic Syndrome in Thai Infants in a retrospectively reviewed patients diagnosed with NS and having onset of the disease in the first year of life who presented in there were 10 patients 7 of them were tested for cmv immunoglobulin 3 of them were cmv IgM +ve and CNS.

In addition, we found a non-statistically significant differences between CMV IgM positive-patients vs CMV IgM-negative patients (P > 0.05) as regarding all blood laboratory investigations (wbcs, platlete, crp, Serum create, Serum albumin, AST, Alt, serum Na, serum K, serum Ca, serum P). However, there were statistically significant decreases in HB (P = 0.024) and serum urea nitrogen (P = 0.04) in IgM positive-patients compared to IgM-negative patients, this also come in agreement with [13] who studied Cytomegalovirus infection and haemophagocytosis in a patient with congenital nephrotic syndrome in a 3-month-old girl.

We concluded that serofrequency of cytomegalovirus infection in pediatric nephrology unit, Zagazig university hospitals during follow-up was 12% for cmv IgM and 100% for cmv IgG at ns children patients.

Copyright: © 2018 Doaa Mohammed Youssef., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.