Kal Alnababtah*

Faculty of Health, Education and Life sciences, Birmingham City University, United Kingdom

*Corresponding Author: Kal Alnababtah, Faculty of Health, Education and Life sciences, Birmingham City University, United Kingdom.

Received: September 04, 2018; Published: October 31, 2018

Citation: Kal Alnababtah. “Kitchen Size and Other Risk Factors Which Relate to the Incidence of Burns in Children”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 1.4 (2018):34-39.

Background: Burns is predominantly severe when occurring in children and resulted from many socio-demographic factors (SDC). As such there is a need to understand risk factors for burns and their impact on children and families. The aim of the study is to explore the relationship between the kitchen size and the housing status with the incidence and mechanisms of burn injuries in children to develop a contextual model with a view to informing future health care policy and health promotion programmes.

Methodology: This study is representing a quantitative part of a PhD observational, cross-sectional, and descriptive study was performed in a UK Paediatric Burn Centre in the West Midlands. The questionnaire was used to collect data from May 2011 to April 2012 and was completed by 160 parents/guardians of children after they were treated from burns. The completed questionnaires have been analysed by using SPSS version 19. Ethical approval has been granted from Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH) and South Birmingham Ethical Approval Committee (SBEAC).

Results: Several key SDF were identified that linked to an increase in the incidence of burns in children. The study has shown that the smaller size kitchens and smaller houses is linked with the occurrence of severe burns in children (p=0.001). Significant burns were found significantly different (p=0.047) in houses consists of separate room kitchens compared with houses consists of kitchen-diner. Incidence of burn injuries during meal-times was significantly high (p < 0.001), burns were significantly increased (p = 0.002) among children when their parents are young (< 25 years old). The results have shown also that burns were increased among children who lived in social/council accommodation and in overcrowded houses with more than 3 children and having small kitchens (p < 0.009).

Conclusion: A range of socio-demographic factors are associated with an increase in the incidence of burns in children. These findings potentially may have clinical utility in informing future health care policy and health promotion/education programmes. These programmes are usually delivered to parents/guardians after burns have occurred, therefore, consideration must be given to the timings of such programmes.

Keywords: Scalds; Spill; Child*; Socio-Demographic Factors; Prevention; Burn*; Epidemiology

PhD: Doctor of Philosophy; UK: United Kingdom; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SDF: Socio-demographic Factors; BSA: Body Surface Area; GP: General Practitioner; P-value: Probability; χ² test: A chi-squared test

Burns are considered one of the biggest wounds and the most devastating injuries children can receive as they have prolonged consequences which are not only physical but can be psychological in addition to the cost of treatment [1]. Burns can cause substantial morbidity, mortality and are amongst the most expensive injuries as they require long hospitalization and rehabilitation to treat the wound and the resulting scars [2]. The effects and outcomes of burn injuries are predominantly severe when children are exposed to this type of insult. This severity can lead to disability, long-term grief, suffering, deformity, and pain, as well as deteriorating intellectual development as they have difficulties getting on in the school environment with other children because of long term treatment [3].

Children are much more vulnerable to thermal burns, more so than any other age groups [3]. This is due to the fact that they may not recognize the risks and dangers associated with flames and hot fluids and surfaces. In addition to that, they have a limited ability to react promptly and properly to these dangerous situations and have slower withdrawal reflexes and thinner skin than an adult [4]. This may result in significant burns that is deep and severe, which require long term treatment. Not all children are under the same risk of burns, some children are more susceptible [5,6]. These huge variations occur in the degree and the seriousness of burn incidences [7]. The variations of the occurrence of burns in children may relate to social and demographic factors. Some of these factors such as their age and gender where boys more than girls [7], while others are related to the housing status such as the where the kitchen size. Burn injuries therefore, have severe economic and social consequences not only to the individuals, but also to the families and societies [8].

The previous studies that investigated the risk factors and the burns in children [3,7,10,11] did not highlighted other factors such as the kitchen size and the housing accommodation types on the occurrence of significant burns in children. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore the relationship between the kitchen size and the housing status, and the incidence and mechanisms of burn injuries in children to develop a contextual model with a view to informing future health care policy and health promotion programmes.

This study is representing a quantitative part of a PhD study, which has used a mixed method approach; quantitative and qualitative. For the purpose of data collection, a survey questionnaire was used to collect quantitative data about the socio-demographic factors [SDF] and the incidence and mechanisms of burns, which covered the period from 1st May 2011 to 30th April 2012. The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been presented in this study because of the nature of sensitivity that accompanies the study of burns. The inclusion criteria included participants must be parents or guardians, regardless of their language, ethnic origin, including children with a new burn’s cases, and participants were able to provide informed consent. Whilst the exclusion criteria were to participants of children with severe burns involving more than 20% of body surface area [BSA], children with minor burns that treated by their GP, and children were requiring on-going treatment for old burn injuries.

The parents/guardian’s addresses have been taken from the admin team of the burns centre a month after their children discharged after the initial treatment. Three reminders have been sent in different times via post to those families not returned the completed questionnaires to encourage them to participate in the study. The final number of the completed returned questionnaires was 160 and that indicate the whole year of data collection.

The questionnaire has been facing piloted by 8 of specialised professionals in burns and after that the ethical approval for the study was granted from the research and development department at BCH and from the SBEAC. The questionnaire was sent to 228 participants in a sealed envelope, which contains an invitation letter, information sheet, consent form, and a prepaid envelope to return the completed questionnaire with the signed consent form. The data has been analysed by the Statistical Package of Social Sciences [SPSS] version 19. Questions were organized into three main independent components: demographics, accidental, and environmental/residence that may contribute to the occurrence of burn injuries among children. For the purpose of this study the SDF that related to the time of burns injury, kitchens size, overcrowded houses, and parents/guardians’ age are highlighted.

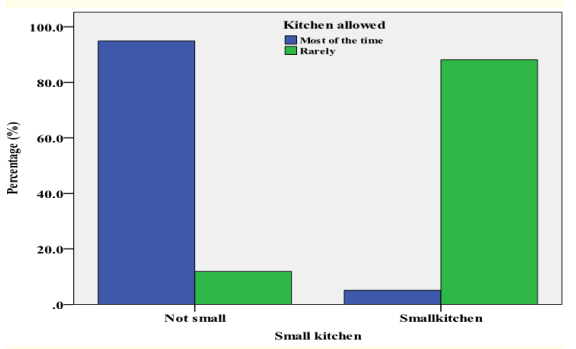

Throughout the reporting period [1st May 2011 to 30th April 2012], there were 246 burns admissions. Of the 246 admissions, 228 patients were included in this study and contacted as they met the inclusion criteria. The total number of participants who returned the questionnaires completed at the end of data collection period was 160 [70.2%]. The analysis of these results has shown that the incidence of burns was significantly higher [p = 0.001] in small sized kitchens in social accommodations compared to owned or private rented housing. On average the results showed that children of younger parents [≤ 25 years age] compared to other parental age group [≥ 25-39 and ≥ 40 years old] had a significantly higher percentage of incidence of burns [p = 0.002] as they were living in houses consisting of small kitchens. Nevertheless, children were living in houses that consist of small size kitchens and one downstairs living room have shown significantly higher percentage of incidence of burns [p < 0.001]. Significant burns were found significantly different [p = 0.047] in houses consists of separate room kitchens compared with houses consists of kitchen-diner. In general children were not allowed to go inside small kitchens as reported by their parents as shown in (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Kitchen size and permission for children to access.

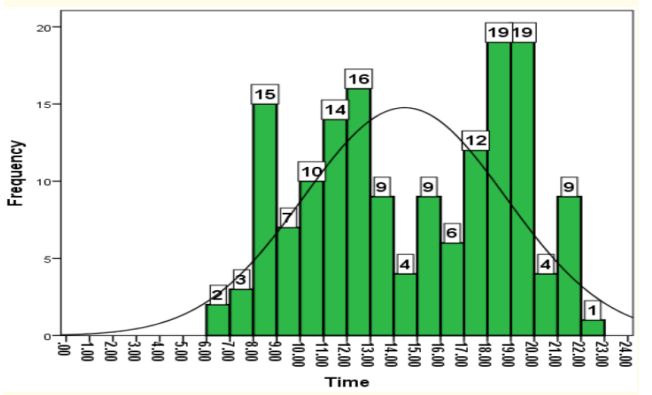

The major peak for burn injuries occurs between 5 pm and 8 pm and continues to decrease steadily hour-on-hour until midnight. A second major peak can be observed between 12 pm and 1 pm which accounts for 15.4% [n=30] followed by 8-9 am peak which accounts for 9.4% [n = 12]. Median is 14.65 hours, first quartile is 11.00 am, third quartile is 18.30, and the inter-quartile range is 17 hours. These values have been taken because the time was not normally distributed as the curve shows (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Time of injury across burn cases.

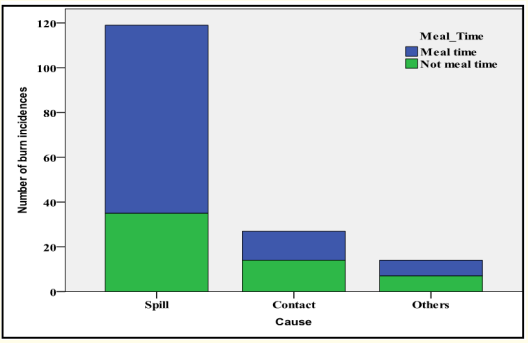

Incidence of burn injuries during meal-times was significantly high [p<0.001], while it was not significantly evident across all causes of burns [p = 0.41]. Causes like ironing or contacts with hot objects can occur at any time during the day, unlike the scalds [spill] burns wherein the majority of these occurred during mealtimes (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Meal-time burn injury and cause of burns.

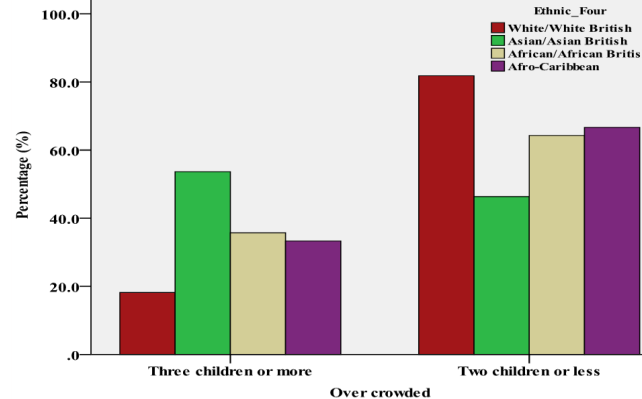

There was a significantly higher percentage of burns [p = 0.001] in overcrowded houses [families having more than three children] in non-White ethnic groups compared to the White ethnic group (Figure 4). Overcrowded families living in houses with small kitchens and one living room showed a significantly higher percentage [p < 0.009] of burn rates than less crowded families.

Figure 4: Overcrowding families and ethnic groups.

The results of χ² test showed that the incidence of childhood burns in single parents from the non-White British group was significantly higher than White British group [p=0.001]. It showed also the significant burns in children living with single parents was significantly higher percentage [p= 0.001] than other children who live with both parents.

It was necessary to cover the whole year from May 2011 to April 2012 of admission to the Burns Centre at BCH as it gives greater insights on types of cases, the causes of burns and a greater response rate, which enhances the confidence in any research results [12]. This survey has shown a reasonable response rate to do that. It can consider the finding of the study with assertion as the sample of participants in this case reveals components of the community with depth and breadth [Fincham 2008]. Not only that, but also the quality of the findings will be inspired by the high response rate and the more accurate results are assured by greater response rate [13-15].

The association between burns injuries among children and the kitchen environment was reported in many studies. In the study conducted by Petridou., et al. [1998] found that two thirds of burns injuries amongst children were scalds, which had occurred in the kitchen. Similarly, Delgado., et al. [2002] reported that more than half of the burns cases that took place in the patient’s accommodation had occurred in the place used for cooking. Over half of scald incidents linked with preparation and consumption of food were also found in studies that searched the prevalent sources and models of burns injury in the developing and developed nations [16]. However, this study has found the relationship between the kitchen size and the greater incidences of burns among children especially when small size kitchens accompanied with social accommodations [p = 0.001], or with one living room [p < 0.001], or with kitchen-diner [p = 0.047]. Small size kitchen has been identified in this study as a kitchen which accommodate one person only to move freely. Therefore, some parents have realised the dangers found in kitchens to their children, especially during the times of food preparations. Subsequently they did not allow their children to enter the kitchen and in particular those kitchens which were smaller in size as the other semi-structured interview part of this study revealed. For other parents, they related these burns injuries to the housing types they live in as the presence of small houses were not giving enough places for their children to move freely or enough playing areas. Therefore, they found themselves in direct contact with dangers that arise from the living room or from the kitchen such as electricity, fire, scalds, trauma and fallings.

Burns in this study among children were significantly high [p = 0.002] when they were living with younger parents [ < 25 years old] compared to other children who are living with parents between 26-39 and ≥ 40 years old. Many of the previous studies found this relationship and most of them related it to the lack of parenting skills as some of these parents haven’t learned the necessary skills to be a good parent [17-19]. Teenage parents, for instance, might have insensible vision about how much attention and care newborns and younger children need [20].

When children were living with single parents or in overcrowded homes have shown a greater risk of getting burns [p < 0.001] compared to children living with both parents and in less crowded homes [three children or less]. Similar findings were supported by previous studies [18,20-23]. Shai and Lupinacci (2003) reported in their study that children’s death resulting from accidental injuries is 3 times more likely when they are living with single mothers and according to Andronicus., et al. (1998), they are also at risk of abuse and neglect. Likewise, children living in overcrowded houses, regardless of their parental age, had an increase of burns [18]. This is due to overcrowding which lead to a lack of vigilance among parents; placing the cooking utensils within reach of children and not providing enough supervision for child activities at home [24,25].

With regards to the burn’s injury time, this study found the greater the incidences occurring during food preparation and meal times. This finding has been supported by a large number of previous studies. Natterer., et al. [2009] observed that there was a direct relationship between food preparation which was in general occurring during meal times and the incidence of burns among children. A study from Iraq also reported similar results where more than two thirds of the scalds [spills] occurred during food preparation and meal time, particularly at dinner time [26]. These results are also consistent with the majority of the reports concerning the time of the accident [27,28,29].

Dissimilarity should be assessed as an encouraging issue in the world of a child so that it will turn into a positive test for socializing and developing. There are a range of socio-demographic factors are associated with an increase in the incidence of burns in children. The housing status were presented to influence the risk of unintentional burns in children. From these, children were living in overcrowded small houses with small size of kitchens were more susceptible to burn injuries because these houses were in most cases missing the initial requirements of safety measures as the study revealed. Therefore, there is a need to inform future health care policy and prevention programmes to include the necessary standards of protection and that houses which allow the freedom of movement to the children in a safe environment. These programmes are usually delivered to parents/guardians after burns have occurred, therefore, consideration must be given to the timings of such programmes.

Copyright: © 2018 Kal Alnababtah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.