Twinomuhangi Sylvia1* and Raymond Mugyenyi2

1

Department of Information Technology, Bishop Stuart University, Uganda

2 Department of Information Technology, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda

*Corresponding Author: Twinomuhangi Sylvia, Department of Information Technology, Bishop Stuart University, Uganda.

Received: July 10, 2018; Published: October 23, 2018

Citation: Twinomuhangi Sylvia and Raymond Mugyenyi. “Factors Leading to Low Male Partner Involvement during Child Birth in Kambuga Subcounty Kanungu District ”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 1.4 (2018):03-16.

The study was about the factors leading to low male partner involvement during child birth in Kambuga sub county Kanungu district, the study was guided by specific objective which included:- to determine the rate of males who accompany their wives/spouses to the health facility during child birth in Kambuga Sub County, to identify the social-economic factors that contribute to men`s low level of escorting their wives during the process of child birth in Kambuga Sub County, to establish strategies in place that help improve male partner involvement during child birth in Kambuga Sub County. The study was descriptive in which both quantitative and qualitative research methods were adopted to obtain necessary data and information from the respondents. The target population in this study comprised of all men of 18 years of age and above in the study area, who were married or had ever been married or had fathered a child in the last two years preceding the study, at Kambuga Sub County health centre III. Researcher used 60 respondents of which 20 men were clients, 38 women both mother and pregnant ones and two health workers from Kambuga Sub County health centre III. The researcher used interview and questionnaires in collecting data. Data from the field was carefully classified, edited basing on clarity, completeness, accuracy and consistence to ensure reliability. The study revealed that 45% of respondents were aware of the male accompanying their spouses to the health service during birth, the rate of males who accompany their spouses was 50% moderately. It was concluded that strategies in place that help to improve male involvement during child birth include 28.3% of infrastructure development, 25% of publicity through radios and televisions, 15% of providing men with information, 14% of education between health workers and local leaders, 11% of cooperation between health workers and local leaders. It was recommended that demonstrations must kick off at all public centres like health units, churches, markets, S/c and Parish headquarters and ensure that all key stake holders are involved to encourage the uptake of men involvement in child birth.

Keywords: Male Partner; Kambuga; Kanungu District

This chapter contains the background, statement of the problem, purpose of the study, objectives and research questions, scope of the study and significance of the study.

Maternal and child mortality remains a public health challenge worldwide. In sub-Saharan Africa, pregnancy and childbirth continue to be viewed as solely a woman's issue. A male companion at maternity care Centre is rare and, in many communities, it is difficult to find men accompanying their spouses to the labour room during delivery. Thus, male involvement in reproductive health has been promoted as a promising new strategy for improving maternal and child health.

There is still slow progress in reducing maternal mortality in Uganda. Male involvement in maternity care has been perceived as limiting mother’s rights to make decisions regarding childbirth. In some cultures, men are not expected to accompany their wives during delivery.

Male involvement in maternity care touches on the sensitive nature of gender roles related to culture, social norms, values and beliefs therefore efforts to involve men in reproductive health must remain sensitive to the needs of women.

Reducing maternal mortality by 3 quarters is goal number 5 of the Millennium Development Goals (MGDs) which is targeted to be achieved by the year 2015. There is still is slow progress in reducing maternal mortality which is due to a number of factors where lack of male partner involvement is among.

Men`s involvement during pregnancy and childbirth plays a vital role in the safety of their female partners Pregnancy and childbirth, by ensuring access to care and provision of emotional and financial support and guaranteeing women’s access to reproductive health services in general The 1994 international conference on population and development in Cairo and the 1995 fourth world conference on women in Beijing endorsed the incorporation of reproductive health services that include men, mandating that Men`s constructing roles be made part of the reproductive health agenda.

The behaviour of men, their beliefs and attitudes affect the maternal health outcomes of women and their babies. The exclusion of men from maternal health care services have contributed to few numbers of women seeking maternity services during childbirth leading serious and life-threatening complications during child birth. Recognition is growing on a global scale that involvement of men in reproductive health policy and service delivery offers both men and women important benefits (Naomi, 2005).

To reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, interventions had been made in the areas of implementation of safe mother- hood initiatives and hospital care. Despite the interventions, studies continue to show that existing strategies to save mothers’ lives has been less successful. This may be due to less emphasis placed on the adverse maternal outcomes due social factors that surround decision making at home in obstetric care (Naomi, 2005).

Despite the interventions, studies continue to show that existing strategies to save mothers’ lives has been less successful. This may be due to less emphasis placed on the adverse maternal outcomes due to social factors that surround decision making at home in obstetric care.

The gap in these studies is that the views of women regarding what they consider to be the roles of men and the extent to which they would want men to be involved have largely been neglected.

The increased emphasis on male involvement in maternity care has subsequently resulted in many studies having been conducted, mostly focusing on decision making and social economic factors as justifications for involving men. Assessing the impact of husbands’ involvement on mother’s health outcome is a basic question driving much work/research on male involvement. (Thaddeus and Maine, 1994; Robey., et al. 1998; Drennan, 1998; Kumar, 1999; Ntabona, 2002; White., et al. 2003; King., et al. 2006).

In kambuga Sub-County, men escorting their wives are done by very few men approximately less than 5%. also, mothers who deliver at the facilities are few possibly due to the little support given by their spouses. Active male involvement intends to improve women’s utilization of maternal health services by pregnant women during delivery and childbirth. The study therefore aims at assessing the rate at which men involve themselves in supporting their wives during childbirth, factors hindering their support and the strategies that can be put in place to reduce this problem.

The aim of this study is to examine critically men’s involvement during childbirth in kanungu district, Kambuga sub-County.

Globally, the low male involvement in maternity services is partly contributing to the low utilization of maternity services by the pregnant women and mothers because of the significant role men have on the health seeking behaviour in their families. Low level of male involvement during child birth has persisted despite several interventions by the District Health office and the Community aiming at encouraging male involvement in maternity services (King., et al. 2006). However, the proportion of males who discuss, support and accompany their wives to seek maternity services in Kambuga Sub County has not been documented. Kambuga Sub County is involving Political Leaders, health workers, Religious leaders, Local Council Members and the village Health Team to encourage every pregnant woman to attend maternity care services with her partner/husband and discuss issues regarding the pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal services with them (Naomi, 2005). Despite the above efforts, low male involvement in maternity services still persist and perceived barriers to male involvement in maternity services in the sub county are not well understood and documented. The researcher intends to find out factors leading to low male involvement during childbirth in Kanungu District, Kambuga Sub County.

To investigate factors leading to male partner involvement in care for pregnancy and childbirth and recommend appropriate strategies to improve male involvement in maternal health care services.

The following research questions will guide the study;

The findings would contribute to the body of knowledge information available in relation to low male partner involvement during child birth and will stimulate further inquiry into factors leading to Low male partner involvement in maternal services as an area for further research.

The findings would be compiled into a report in fulfilment for the requirement for the award of bachelor’s degree of public health of Bishop Stuart University. 1.6 Scope of the Study.

The study mainly focused on identifying factors responsible for low male involvement during child birth in Kambuga Sub county Kanungu district, assessing the factors of low male involvement during child birth and suggesting strategies for increasing male involvement during child birth.

The study was conducted in parishes of Ruhandagazi, kiringa and Nyarugunda with in Kambuga Sub County in Kanungu district. Kanungu district is found south western Uganda, it is bordered by Rukungiri District to the north, Kabale District to the east, Kisoro District to the south and DRC to the west.

The study was carried out between January and April 2015 for the collection of primary data because this is the convenient time for the researcher to complete the study.

The researcher faced a problem of insufficient funds for carrying out the research, this was addressed by mobilizing funds from friends, relatives and parents.

The researcher faced a problem of lack of cooperation from respondents as some could hide information, this was addressed by explaining the purpose of the study and made clear to respondents that it was for study purposes and recommendations of which could it could be used to improve health care services.

This chapter presented the literature that is relevant to the study giving reference to the study objectives, sub-divided into three sections. The literature involved opinions and views of other scholars and researchers that are related to the topic in study.

Worldwide, the last 15 years have witnessed increasing global recognition of the importance of men’s involvement in sexual and reproductive health (SRH). Issues such as AIDS epidemic have reinforced the urgency of encouraging men to take responsibility for their own sexual reproductive health and that of their partners [1]. Despite global recognition at the level of international agreements, many countries have not developed large scale programs that reach out to men. As a result, many men are not aware of why they need to be involved in SRH, how they can be involved, and what services are available for them and their partners.

The humanitarian crises in northern Uganda has degenerated the health sector over the last 20 years. This has had an adverse effect on the reproductive health status of women, men and in the region. At 31% in northern Uganda which is the lowest in the country at delivery time men do not escort their wives because of lack of transport due to poverty caused by war which destroyed their property [2].

As a result of increased availability of cultural norms, men’s involvement in maternal health care services is low. Cultural norms have heavily impacted men with negative attitudes towards their involvement with their partners in accessing services [2].

In Turkey, it was observed that health care workers were not supporting men who wanted to engage in child birth, the same study noted that a lot of men come to the clinic with their wives, but it stops at the door [3].

In sub Saharan Africa, Bulut and Molzan [4] reported that societal definitions of gender roles, lack of information and significant barriers within the health care system itself as some of the issues cited by clients as impediments to father’s participation in child birth. Long working hours and difficulty in taking time off work to attend services also cited as reasons why many men would be unable to participate in child birth. While mboizvo and Basset [5] stated that failure to target men in programs has weakened the impact of reproductive health programs, since men can significantly influence their partners reproductive health decision-making and use of health resources.

A study done in Kenya, husbands’ presence during labour was mostly restricted by cultural and traditional beliefs that men became important when they see delivery blood and men losing the potential spiritual powers of their amulets(jujus) when they witnessed their spouse deliver. Some of these beliefs ran through different ethnicities and some were specific to certain ethnicity (Jallow, 2007).

In Tanzania, some social values even restrict physical contact of men and the newly born baby in the first seven days of postpartum [6].

In Senegal, gender difference and preference of the male child feature prominently. Women who deliver male children are provided with good nutrition by their husbands during the postpartum period. This shows some sort of gender inequality and some women who deliver baby girls in health facilities feel discomfort to inform their husbands who are most often not available at clinics [7].

In Gambia, most research studies reported difficulties of men being in clinics together with their partners during the delivery process. One of the reasons is the limited space to accommodate both parties in the labour ward. Most labour wards are open and not constructed in cubicles. It is reported that if husbands are allowed in labour wards to be with their labouring partners, they will possibly see other labouring women different from their own wives. This is mostly regarded as something against the teaching of Islam [8].

A qualitative study conducted in Gambia, most women and some men expressed views that some of the attitudes of midwives towards labouring women were labouring unacceptable, especially female midwives. They used abusive languages against their female counter parts in labour and at times reluctant to answer to labouring women’s call for help. Men were as well at times sent out of the labour ward. In instances where men mistakenly entered labour wards while in the process of giving care, they were shouted at by nurses (midwives)and they became bewildered by Republic of the Gambia.

A study conducted in Ghana found out that, some men expressed their views that involvement and presence of men during the delivery process is a western cultural practice that should not be adopted. Pregnancy and child birth as well as care of the children in the family were seen as women’s responsibility. Men who offered birth care during birth of their children, help them change their clothing and cuddled them were seen as renegade by some men [9].

Economically, some men feel it is a duty to facilitate their wives in terms of transport, and if they do not have means of transport they see no point in escorting them while both are walking. Yet in many situations in Africa where a man is economically in position to provide the basic necessities of life, he tends to have more than one wife, which also negatively affects his willingness and ability to escort the wife to deliver (Ractifile, 2001).

Multiple partner relationships promote different interests for the man and his partners and this will hamper possibilities for transparent decision making on maternal issues in addition to involvement in maternal health services of all his wives when needed. Reporting his findings, Ractifile (2001) noted that men are often involved in multiple sexual relationships that present considerable challenge to fertility awareness and reproductive health programs.

Alcohol consumption by men has also been noted to play an important role in keeping men away from the involvement during child birth as most of the time they may be drunk, leaving them with no money or time to facilitate the needed care (UNPF 1999).

In Zimbabwe, communicating with men have been reported by some researchers to pose challenges for programmes which historically have focused on serving women [10]. It is not easy to design messages and materials that men find persuasive but that also promote gender equality and women empowerment. Most men misinterpreted campaign messages promoting male involvement to mean that decisions should solely be left to men [10]. Sometimes couple dialogue may be the problem, once there is a communication breakdown for one reason or the other, the whole family function fails.

Green., et al. [11] noted that researchers and reproductive health service providers have tended to describe women’s disadvantaged positions without men’s roles. This has resulted in some reproductive health programmes designed to improve women’s reproductive health to consider men as part of the solution.

Studies show that there is a general lack of interest on the part of men in some countries in Africa in their partners reproductive health [12]. Men often do not have access to information on maternal health issues and on their role in promoting maternal health resulting into majority of the men to have sufficient information and knowledge with regard to maternal health. Kasolo and Ampeire [13], highlighted an example of break down in communicating among couples was when they reported that some men did not want to discuss ANC attendance with pregnant women because they considered pregnant women to nag a lot.

Work commitments, including husbands working elsewhere, low job security and high unemployment can also prevent men from engaging in child birth [14].

In many places, clinics have not been designed to include both men and women. Lack of physical space for confidential consultation can make the presence of men problematic, and insufficient space in waiting rooms may be daunting for men who attend clinics with their partner or children [15].

Other barriers reported by Mullany [16] include a man not being invited to attend, fear of being perceived as jealous husband following his wife around in some cases, men not wanting to make their relationships with their pregnant partner publicly known for fear of limiting their chances with potential girlfriends.

In Uganda, few interviews expressed views that men spend money lavishly on social programmes like weeding’s and other ceremonies rather than giving priority to health of women. (United Nations development programme 2007 - 2008 report).

In Uganda, maternal child health (MCH) services implementers largely ignored and providers largely ignored the role of men. However, since the onset of HIV/AIDS, pandemic, many efforts are now being made to reach men, especially regarding HIV/AIDS (UNPF, 1999).

In Uganda, a study done by WHO department of reproductive health and research (2009), husbands’ limited time to be in clinics together with their spouses was further complicated by long waiting time for antenatal and laboratory services. Many expressed feelings that they spent long times in clinics to receive antenatal and reproductive health services and husbands cannot waste their precious time in clinics just waste their time in clinics just waiting for services.

Distribution of information, education and communication (IEC) materials can also increase men’s positive influence on maternal and child health. in the community, randomized controlled trial in rural Pakistan [17], volunteers in the intervention communities distributed audiocassettes and booklets on care during pregnancy, maternal and new born danger signs to women only, or to women and their male partners. Although the study was inadequately powered to deduce significant differences between couples and women only intervention clusters, two years after the materials were distributed; a district wide survey revealed that more men accompanied their wives for check-ups and delivery.

Mass media campaigns can be effective in improving knowledge and changing cultural attitudes. In many settings, mass media is a significant source of sexual and reproductive health information for men [18]. In Indonesia the Suami SIAGA campaign promoted greater male involvement in ensuring safe mother hood programmes via TV, radio and print materials.

Clinic based initiative to engage men; antenatal care provides opportunities to provide men with information, self-risk assessment, condoms and early detection and treatment of STIs [19]. men do not traditionally attend antenatal clinics but experience in lao PDR, India amongst other countries suggest that when they are encouraged, they are keen to do so [20]. Several authors suggest that making the first antenatal visit a routine couple visit as this visit often includes STI and HIV testing as well as long counselling sessions regarding nutrition, workload and health issues during pregnancy. Attendance at the first visit also ensures that male partners receive messages about health during pregnancy and preparation for birth as early as possible.

Providing verbal or written invitations for men to attend ANC with a pregnant mother may increase male partner attendance. A routine invitation letter delivered via a pregnant partner can increase male involvement in ANC [21] and is already common practice in some settings. In Vientiane, Laos, a pilot project to increase male involvement in ANC through a simple invitation letter from health care providers to expectant fathers resulted in 62%of invited fathers attending maternity services.

Group education can change behaviour amongst men. in the quasi experimental intervention for Nigeria men discussed earlier, intended to reduce the risk of HIV and, STIs intended pregnancy, (Exner, 2009), men were non randomly assigned based on place of residence to either an intervention arm receiving two 5-hour workshops, plus a monthly two hour check -in at 1and 2month post-intervention, or to a comparison group that received a halfday didactic workshop. At three months follow -up, those in the intervention group were most likely to report condom use at last, intercourse less likely to report vaginal sex, more likely to report self-efficacy in sexual negotiations and more equitable gender relations with primary partner and greater intentions for future condom use.

Male involvement activities do not need to be expensive. The experiences of organizations such as Engender health, an NGO working to involve men since the mid1990s,reveals that successful male involvement initiatives need not be expensive and are achievable even in resource poor settings [22] incorporating sessions on working with men in health worker training, inviting expectant fathers to attend antenatal clinics with their pregnant partners, making clinic environment conducive to men and facilitated community sessions on pregnancy and child birth an all be delivered at relatively low cost.

Male involvement activities should seek to address men’s own health needs and concerns as well as the needs of their female partners and children. Common criticism of such programmes is that they seek to involve men to support health improvements for women and children without consideration of men’s own health needs [23]. Providing a comprehensive service that addresses men’s concerns about maternal and child health, as well as linking men to services that boost their own health, is likely to lead to better health outcome for the community as a whole. This approach is also likely to be more successful in fostering positive male involvement in their spouse’s child birth.

Male involvement should target men in different age groups with messages and strategies specific to life stages and population groups [24]. Programmes that use a life cycle approach, engaging men thru different life stages, are rare [25]. But evidence suggests that men respond better to communication strategies and messages that are tailored to their particular life situation and that adapt as men move though different life stages.

Programs that seek to address gender inequalities that that lead to poor health outcomes are often more successful than those that accommodate or work around gender in equalities. In 2007, WHO conducted a systematic review of interventions to improve gender-based inequality and equity in health. Some 58 programs were ranked according to the gender approach employed (gender neutral, gender sensitive or transformative) and overall program effectiveness. Programs that were able to transform gender roles and promote more gender equitable relationships between men and women were found to be more effective than those that neither reinforced nor challenged gender roles.

Effecting positive changes in gender relations will be challenging in most contexts [26]. Such initiatives often face resistance at community, policy and program levels from those who review prevailing gender relations as an integral part of culture and attempts to transform gender relations as weakening of values and traditions. Male involvement initiatives may seek to identify cultural norms that are conducive to, or supportive of more equitable relationships between couples for the purpose of greater male involvement in their spouses’ child birth [27-43]

The most successful male involvement programs integrate different types of strategies. The 2007 WHO review further found that programs that integrate group education with community outreach, mobilization or mass media campaigns are the most effective in changing behaviour [19].

Peer educators can be successful in educating accurate health information among men. Peer educator spread ideas and accurate information through one by one visits, group discussions and community events. In settings where men feel more comfortable receiving sensitive information from other men or perceive other men to be a more credible source of information, using male peer educators, outreach.

This chapter presented a detailed description of the methodology that was used in data collection. It included research design, area of the study, target population, sampling procedures, data collection methods, data collection instruments, research procedure, data analysis and limitations of the study.

Brick and wood (1998) states that the purpose of a research design is to provide a plan for answering the research question and “is a blueprint for action”. It was the overall plan that spells out the strategies that the research uses to develop accurate, objective and interpretative information. This study employed descriptive of a subject. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods were adopted to obtain necessary data and information from the respondents. Quantitative was used to obtain quantifiable data, while qualitative method was used to probe how respondents understand the topic of the study.

The study was carried out in parishes of Ruhandagazi, Kiringa and Nyarugunda with in Kampala Sub County in Kanungu district is found in south western Uganda, its boarders with Rukungiri in north, Kabale district to the east, Kisoro to the south and DRC to the west. The area is located at about 450KM from Kampala capital city.

The target population in this study comprised of all men of 18 years of age and above in the study area, who were married or had ever been married or had fathered a child in the last two preceding the study in which of those whose spouses are pregnant mothers and pregnant women attending maternal health services during the period of the study who were contacted in the study as well as the health workers at Kambuga Sub County health centre III.

Cooper and Schindler (2000) states that the sample size is the selected element or subset of the population that is to be studied. The researcher will target a sample size of 60 respondents from a population size of 155 people.

n=N1Ne2

Where n = sample size, N = Estimated convenient number of respondents, e = marginal error or level of significance and it ranges from 1% - 5% which is 0.01-0.05, thus

n=155×155(0.052)

n=24025(0.0025)

n=60

From the above formula the researcher used 60 respondents of which 20 men were clients, 38 women both mother and pregnant ones and two health workers from Kambuga Sub County health centre III.

The researcher used simple random sampling techniques to select men; women and pregnant women while purposive was used to select health workers because they offer health care to clients.

The researcher had one to - one conversation with the respondents with aim of getting the information. This was applied to men, mothers and pregnant women because they were able to read and write yet they had information.

Questionnaires are efficient data collection mechanism when the researcher knows exactly what is required and how to measure the variables of interest (Sekaran, 2004). In the same line as interviews, questionnaires were also categorised as structured, semi- structured. The main reason to use questionnaire was because it was time saving. It was applied to health workers

The researcher obtained an introductory letter from the head of department public health of Bishop Stuart University that was taken to the respective authorities in the field to seek permission to conduct the study. Before administering questionnaires, respondents were informed about the research objectives, benefits and how the research findings were disseminated so that they could make well-grouped decisions whether they would participate.

Data from the field was carefully classified, edited basing on clarity, completeness, accuracy and consistence to ensure reliability. Data analysis was based on the objectives of the study and done by use of computer programmes like Microsoft word, Microsoft excel, on collected data to draw meaningful interpretation and conclusion gave findings and suggestions. Simple descriptive statistics like frequencies and percentages were generated thus tables were used in data presentation.

This chapter attempts to analyze the data collected and its interpretation in relation to the studied subjects. The empirical findings of the study are presented, analyzed and interpreted. The collected data was organized from the responses to questionnaires administered to health workers, pregnant women and spouses.

This section presents socio-economic and demographic characteristics of respondents which include; age, sex, level of education and marital status. The data on the respondents’ demographics is summarized in the frequency distribution table as showed in figures below.

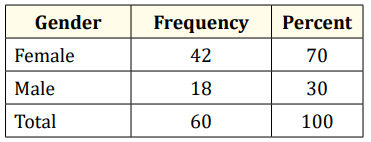

Findings are presented in the table 1 below showing distribution of respondents by Gender

According to the research findings in table 1 above, 42 (70%) of respondents were females while 18 (30%) of the respondents were males.

Table 1: Source: Primary data, 2015.

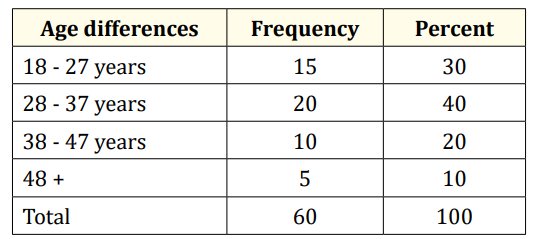

The findings are presented in the table 2 below Showing Respondents’ Age.

Table 2: Source: Primary data, 2015.

In table 2 above, the study revealed that almost a half of the respondents were in age range of 28 - 37 years, 15 (30%) of respondents were in age range of 18 - 27 years, 10 (20%) of respondents were in age range of 38 - 47 years and 5 (10%) in age range of 48+ years.

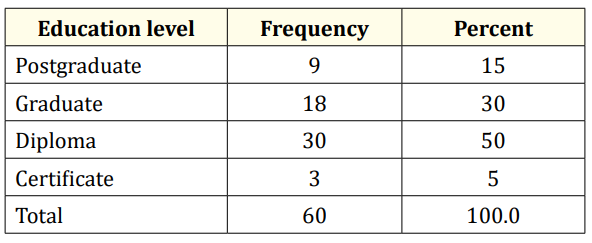

Findings are indicated in the table 3 below showing respondents’ education level.

Table 3: Source: Primary data, 2015.

Study findings in table 3 shows that the half of the respondents, 30 (50%) had diploma level of education, 18 (30%) of respondents had graduate level of education, 9 (15%) of respondents had postgraduate of education, and 3 (5%) of the respondents had certificate level of education.

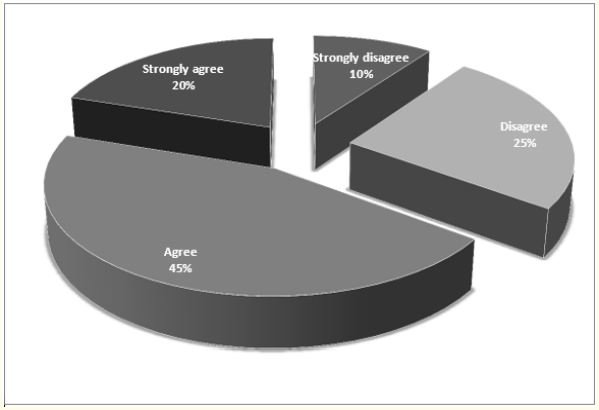

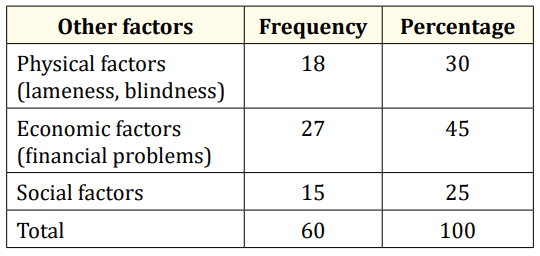

Various questions were set in relation to this sub heading Awareness of male accompanying their spouses to the health service during birth. Findings are indicated in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Source: Primary data, 2015.

Figure 1 indicates that 45% of respondents agreed that they are aware of the male accompanying their spouses to the health service during birth, 25% of respondents disagree, 20% of respondents strongly agree and 10% of respondents strongly disagree.

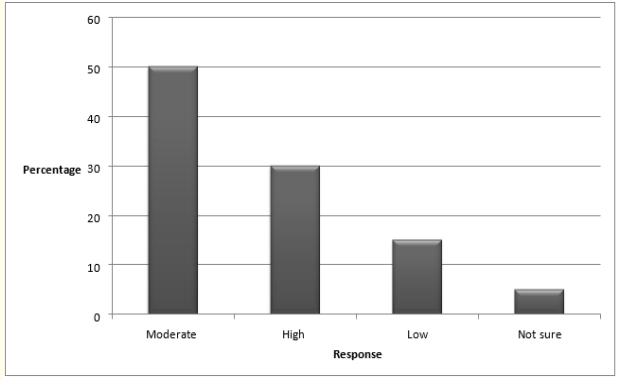

The rate of males who accompany their spouses to the health facility during childbirth. Findings are presented in figure 2.

Figure 2: Source: Primary data, 2015.

From figure 2 above, the study revealed that 50% of the respondents moderately stated that spouses accompanying their wives, 30% state that it was high while 15% said it was low and 5% were not sure.

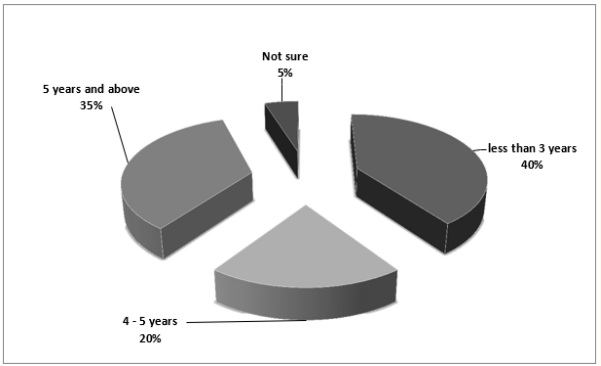

The period of how males have been accompanying their spouses to the health facility during childbirth findings are presented in figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Source: Primary data, 2015.

From the field, most of the respondents (40%) mentioned less than 3 years, followed by 35% of respondents who mentioned 5 years and above, followed by 20% of respondents who mentioned 4 - 5 years and the least of respondents 5% were not sure.

Various questions were set in relation to this sub heading and these questions were addressed to a cross section of 60 respondents who contributed primary data.

Family back ground influence the contribution of men’s level of escorting their spouses during the process.

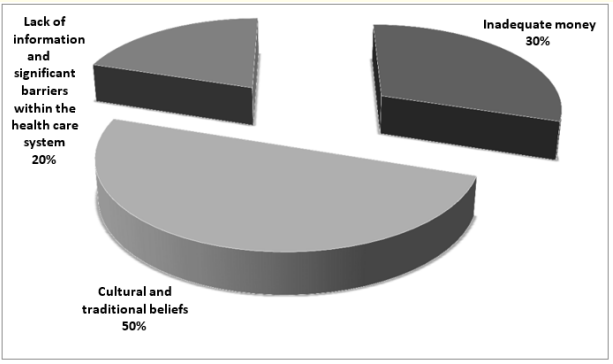

The first question aimed at assessing how family background influence the contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process of childbirth. Findings are presented in figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Source: Primary data, 2015.

From the findings from 4 above on, how family background influences the contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process of childbirth found out that, 50% of respondents talked about cultural and traditional beliefs, 30% of respondents talked about inadequate money and 20% of respondents talked of lack of information and significant barriers within the health care system.

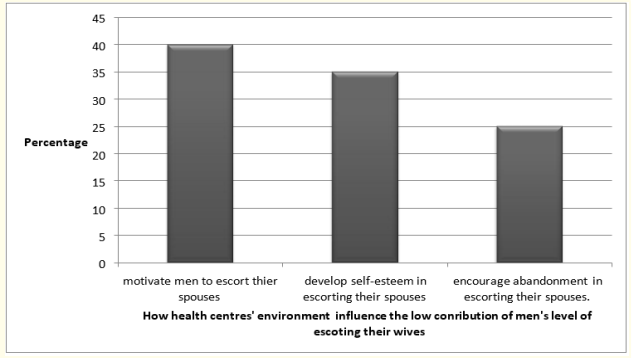

Health centers’ environment influence the low contribution of men’s level of escorting their spouses during process of childbirth Findings are presented in figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Source: Primary data, 2015.

Figure 5 above revealed that 40% of respondents talked that health centers’ environment motivate men to escort their spouses, 35% of respondents talked of developing self-esteem in escorting their spouses and 25% of respondents talked of encouraging abandonment in escorting their spouses.

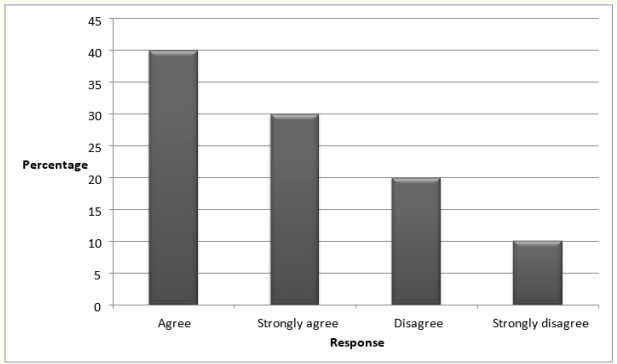

Other factors that lead to the low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process of childbirth in Kambuga Sub-County Findings are presented in table 4 below.

Table 4: Source: Primary data, 2015.

From the findings in table 4, 18 (30%) of respondents indicated physical factors (lameness, blindness), 27 (45%) of respondents indicated economic factors (financial problems) and 15% of respondents indicated social factors.

Various questions were set in relation to this sub heading.

There are suitable intervention measures in reducing the low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process of childbirth the findings are presented in figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Source: Primary data, 2015.

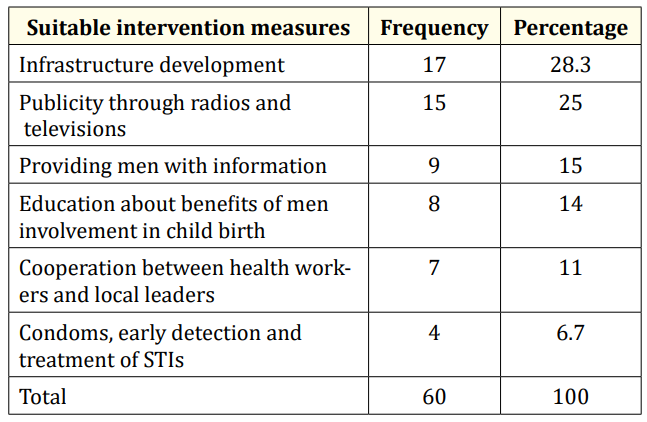

Suitable Intervention measures in place aiming at reducing low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives. The findings are presented in table 5 below.

Table 5: Source: Primary data, 2015.

From table 5 above, 17 (28.3%) of the respondents indicated infrastructure development, 15 (25%) of respondents indicated publicity through radios and televisions, 9 (15%) of respondents indicated providing men with information, 8 (14%) of respondents indicated education between health workers and local leaders, 7 (11%) of respondents indicated cooperation between health workers and local leaders and 4 (6.7%) of respondents indicated use of condoms, early detection and treatment of STIs.

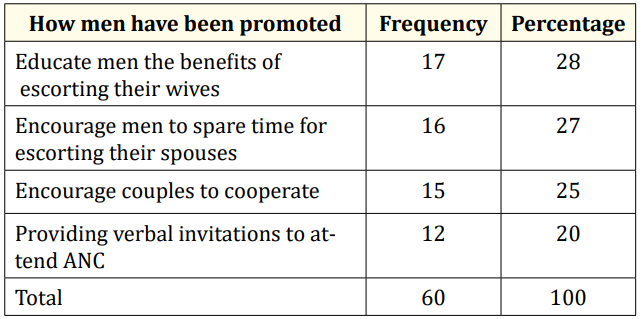

Promoting contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process of childbirth the findings are presented in table 6 below Suitable Intervention measures in place aiming at reducing low contribution of men’s level of escorting their spouses.

Table 6: Source: Primary data, 2015.

From the study findings in table 6, 17 (28%) of respondents indicated educate men the benefits of escorting their spouses, 16 (27%) of respondents indicated encouraging men to spare time for escorting their spouses, 15 (25%) of respondents indicated encourage couples to cooperate, 12 (20%) of respondents indicated providing verbal invitations to attend ANC.

This chapter presents discussion of the study findings from the research study and gives recommendations.

The main aim of this study as indicated in chapter one was to assess the factors leading to low male partner involvement during child birth in Kambuga Sub county Kanungu district. The subsequent discussion in this chapter is based on the results presented in chapter four of this report as given by the respondents.

Reference to the above sub heading, the study revealed that 45% of respondents were aware of the male accompanying their spouses to the health service during birth, the rate of males who accompany their spouses 50% moderately. The study also revealed that 40% of males have been accompanying their spouses to the health facility during child birth less than 3 years.

The above study finding is in line with UNPF (2009), that men has also been noted to play an important role in keeping men away from the involvement during child birth as most of the time they may be drunk, leaving them with no money or time to facilitate the needed care.

The study revealed that 50% of respondents revealed cultural and traditional beliefs influence the contribution of men’s level of escorting their spouses during the process of child birth, the study also revealed 45% of respondents revealed economic factors (financial problems) lead to the low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process.

The above study finding is in line with Ractifile (2001), economically, some men feel it is a duty to facilitate their wives in terms of transport, and if they do not have means of transport they see no point in escorting them while both are walking.

The study revealed strategies in place that help to improve male involvement during child birth include 28.3% of respondents revealed infrastructure development, 25% of respondents revealed publicity through radios and televisions, 15% of respondents revealed providing men with information, 14% of respondents revealed education between health workers and local leaders, 11% of respondents revealed cooperation between health workers and local leaders and 6.7% of respondents revealed using condoms, early detection and treatment of STIs.

The study also revealed suitable Intervention measures in place aiming at reducing low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives, these included; 28% of educating men the benefits of escorting their spouses, 27% of respondents revealed encouraging men to spare time for escorting their spouses, 25% of respondents revealed respondents revealed encouraging couples to cooperate, 20% providing verbal invitations to attend ANC.

The above study findings are in line with Char., et al. [18]. Mass media campaigns can be effective in improving knowledge and changing cultural attitudes. In many settings, mass media is a significant source of sexual and reproductive health information for men. In Indonesia the Suami SIAGA campaign promoted greater male involvement in ensuring safe mother hood programmes via TV, radio and print materials.

It is concluded that the respondents were aware of the male accompanying their spouses to the health service during birth, the rate of males who accompany their spouses 50% moderately, 40% of males have been accompanying their spouses to the health facility during child birth in period of less than 3 years, 50% of respondents concluded that cultural and traditional beliefs influence the contribution of men’s level of escorting their spouses during the process of child birth, 45% of respondents concluded that economic factors (financial problems) lead to the low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives during the process.

The study also concluded that strategies in place that help to improve male involvement during child birth include 28.3% of respondents infrastructure development, 25% of publicity through radios and televisions, 15% of providing men with information, 14% of education between health workers and local leaders, 11% of cooperation between health workers and local leaders and 6.7% of using condoms, early detection and treatment of STIs.

It was also concluded that suitable Intervention measures in place aiming at reducing low contribution of men’s level of escorting their wives include 28% of educating men the benefits of escorting their spouses, 27% of encouraging men to spare time for escorting their spouses, 25% of encouraging couples to cooperate, 20% of providing verbal invitations to attend ANC.

From the findings of the study, the following recommendations should be given consideration by the Non-Governmental Organizations, and government through the Ministry of Health in conjunction with the Ministry of Local Government as flows.

Demonstrations must kick off at all public centres like health units, churches, markets, S/c and Parish headquarters and ensure that all key stake holders are involved to encourage the uptake of men involvement in child birth.

The government of Uganda through the Ministry of Local Government should increase of district health staff remuneration so as to cope up with the increasing public demand on sensitization and awareness on benefits of men in escorting their spouses to health service during child birth.

Decision makers in Ministries and funding agencies need to design policies and programs to improve health service.

Factors hindering government efforts to develop and implement of male involvement health service during child birth in Uganda Need for a comparative study. More research should be done in other districts of Uganda, so as to compare with the results got from Kambuga Sub-County Kanungu district and have a better ground for recommendation.

Copyright: © 2018 Twinomuhangi Sylvia and Raymond Mugyenyi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.