Gihad Al-Saeed1*, Tamer Rizk2, Khalid Mudawi3, Bayan Amin Al-Ramadina1 and Ibrahim Al-Saeed4

1Consultant Pediatrician, Al-Takhassusi Hospital, HMG, Riyadh, KSA

2Consultant Pediatric Neurologist, Al-Takhassusi Hospital, HMG, Riyadh, KSA

3Consultant Pediatrician, Sidra Medical and Research Center Doha, Qatar

4Internship Medical Student, Faculty of Medicine, Milano University, Italy

*Corresponding Author: Gihad Al-Saeed, Consultant Pediatrician, Al-Takhassusi Hospital, HMG, Riyadh, KSA.

Received: May 11, 2018; Published: June 11, 2018

Citation: Gihad Al-Saeed., et al. “Vaccine Hesitancy Prevalence and Correlates in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia”. Acta Scientific Paediatrics 1.1 (2018):05-10.

Background: Incidence of vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) is on the rise globally in both developed and developing countries. 700 cases of confirmed measles were diagnosed in 2017 in Italy alone. It is recommended that 95% of the population should be immunized to achieve herd national immunity [1].

Vaccine delay seems to be the main reason for under vaccination. There are many children with incomplete vaccination schedule globally. Health authorities and academic institutions started to investigate vaccine hesitancy in order to solve this worsening crisis [1].

Objectives: Our objectives were to evaluate the magnitude and level of vaccine hesitancy problem amongst children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We aimed also to examine the effects of social, economic and educational factors on vaccine hesitancy.

Methods: A random sample of parents attending our outpatient department (OPD), for reasons not related to vaccination, were interviewed. Using a standard questionnaire, parents were asked a number of questions to evaluate their knowledge, attitude and behavior towards vaccines. The questionnaire included questions about the number of children in the household, educational level of parents, economic status, and the main source of parents’ information about vaccines.

Parents’ knowledge of Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs) and vaccine safety was assessed in order to identify the parents’ level of vaccine hesitancy. Parents’ impression about the Saudi vaccination schedule; recommended by the ministry of health; has been examined as well. Any significant delay, for more than one month of the recommended date of vaccination, in one or more child has been documented. The reasons for vaccination delay have been explored. Statistical analysis of data was done to highlight the main features of the hesitant groups.

Results: Some form of vaccine hesitancy (VH) was found in 15% of our sample. 34% of parents reported significant delay in giving vaccines to a child or more. However, only 2.5% of them delayed vaccines intentionally because of doubts about vaccines importance.

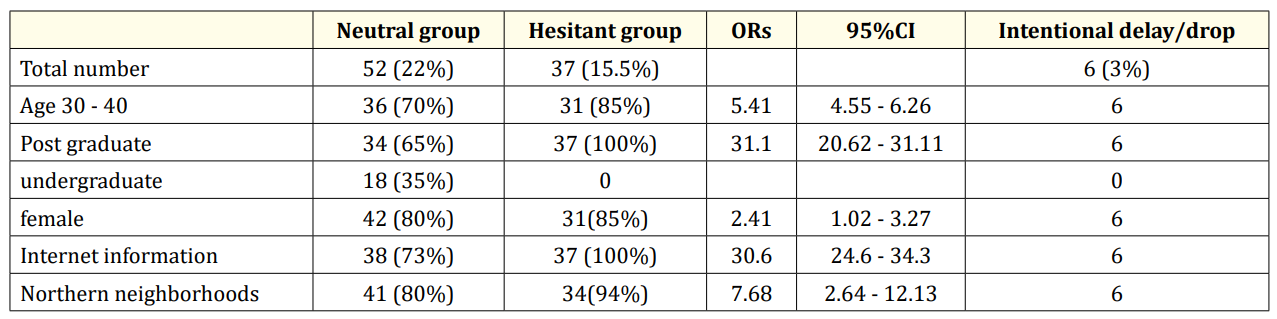

Conclusions: One seventh of parents has shown some degree of VH spectrum. However, minority intentionally delayed or dropped vaccination. Risk factors for vaccine hesitancy were: middle age group 30 - 40 years (OR = 5.41. 95%CI: 4.55 - 6.26), female gender (OR = 2.41. 95%CI: 1.02 - 3.27), high level of education (OR = 31.11. 95%CI: 20.62 - 41.11), Living in the northern affluent geographical areas (OR = 7.6, 95%CI: 2.64 - 12.13), and using social media as the main source of information (OR = 30.6, 95%CI: 24.6 - 34.3).

Misinformation and concerns about vaccine safety did not affect parents’ decision to vaccinate their children. However growing number of cautious acceptance and acceptance with misinformation seems alarming and needs early practical interventions.

Keywords: Vaccine Hesitancy (VH); Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs); Vaccination

Vaccination is considered as one of the most successful public health interventions of the 20th century. Consequently, fear has shifted from many vaccine preventable diseases to fear of the vaccine itself. It seems that vaccine is the first victim of its own success. Previous confidence in vaccines is deteriorating. Many authorities currently talk about “crisis of public confidence” in vaccines or VH [2].

Vaccine hesitancy (VH) is defined as delay in acceptance of vaccination or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services. The definition does even involve acceptance of vaccination with doubts about its safety and benefits. These behaviors and attitudes vary according to personal profile of vaccines [1].

VH among Doctors is defined as reported doubts about risks and benefits of vaccines or low vaccine acceptance for themselves.

A study on MMR vaccine hesitancy in USA, has shown that 5% drop in the vaccine coverage would triple the number of measles cases in children nationally every year. These results support an urgent need to address vaccine hesitancy in policy dialogues at the state and national level with consideration of removing personal belief exemptions of childhood vaccination [3].

Four main sociocultural changes have contributed to vaccine hesitancy: 1- Low level of trust in large corporations that manufacture vaccines. 2- Growing public interest in natural and alternative types of medicine. 3- The medical role has changed. Parents no longer want to be told what to do for their children, but rather want a shared decision-making process. 4- Pediatricians are increasingly under pressure to see more patients in less time and find themselves confronted with parents that find misinformation on the internet. Further, they find it more difficult to communicate accurate information to parents and address their concerns [2].

It is estimated that less than 5 - 10% of individuals have strong anti-vaccination convictions. However, a more significant proportion could be categorized as hesitant. Vaccine hesitant may refuse some vaccines but agree to receive others. they may delay vaccines or accept vaccines according to the recommended schedule but be unsure in doing so. Many scientific studies have demonstrated the negative influence of media controversies on vaccine uptake [4].

Only 51% of the websites provided correct information about the fact that no association has even been demonstrated between MMR and Autism. One large study showed that surfing anti-vaccination website for 5 - 10 minutes had a negative influence on risk perceptions regarding vaccinations and on the decision to vaccinate one’s child [4]

7% of children living in Australia are not fully vaccinated, less than half are not vaccinated because their parents are so worried about vaccines’ safety. More than half have been prevented from accessing vaccination by practical barriers. Many new parents have questions or concerns about vaccines’ safety and necessity. Vaccine scares, whether rumors or theories about vaccines being harmful, or genuine safety issues, can undermine parents’ confidence in the safety of vaccination. The MMR-Autism scare led to a national outbreak of measles in 2013 in the UK and it took years for vaccination rate to recover [5].

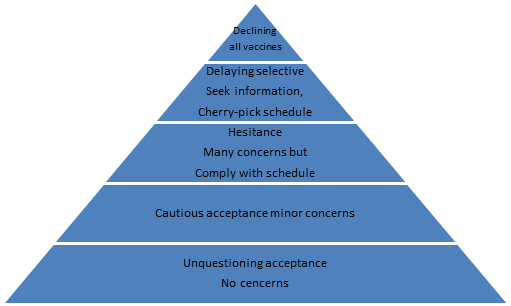

Parents’ confidence in the safety and need for vaccination is best described as spectrum ranging through: unquestioning acceptance, cautious acceptance; hesitance; delaying or selective vaccinators; to those who decline all vaccines (Figure 1). Parents often move from one position on this spectrum to another. New parents may not have thought much about vaccination and simply accept it as ordinary, then a bad experience with the healthcare system triggers mistrust, they revise their position and begin declining the vaccines [6]. It is the hesitant parents who are most likely to change their positions.

Figure 1: Parents’ attitude towards vaccination.

Pew research center found in a recent study that 41% of the young adult parents (< 30 years) believe that vaccination should be the parents’ choice [7].

Educational, economic, and cultural factors affect the vaccination trend. Reluctance to vaccinate was associated with health believes particularly among well-educated upper and middle-income segments of the population [7].

Study in Mattel children hospital in Malibu. USA, Dr. Nina Shapiro the director of pediatric ENT department found that in one elementary school in the city wealthier areas only 58% of students were vaccinated as compared to 90% of all students across the state. Similar rates were found at other schools in wealthy areas. In another private school only 20% of kindergarteners were vaccinated [7].

In 2005 it was found that social networks excreted the strongest influence in the decision to not vaccinate. This means that as much as non-vaccination is an economic trend, it is also a racial and cultural trend, reinforced through the shared values, believes, norms, and expectations common to one’s social network [7].

In 2009 the national immunization survey in USA disclosed that 25.8% of parents with children aged 24 - 35 months had delayed vaccines, 8.2% refused vaccines, 5.8% both delayed and refused vaccines. Parents who delayed or refused vaccines were less likely to believe that vaccines are necessary to protect the health of children (70% vs 96%) and that vaccines are safe (50.4% vs 84.4%) [8].

In 2016 national survey 13.5% of the respondents from the USA stated that they disagree that vaccines are safe, and the situation is worse in Europe, where the number gets as high as 41%in France. many opponents also see mandatory vaccination programs as an infringement of their freedom [9].

Children of parents who delayed or refused vaccines also had significantly lower vaccination coverage for 9 of 10 recommended children vaccines including: DTaP, POLIO, MMR [8].

Public health communicators move beyond the knowledge deficit model of communication to develop messages tailored to the audience needs; to use new tools such as social media and to be proactive rather than reactive to vaccination scores [10].

A random sample of 500 children, whose parents attended the pediatric outpatient clinic department in Al-Takhassusi hospital; HMG in Riyadh, KSA between June 2017 and September 2017 were evaluated for this study. All parents of acutely ill children and parents who came with their children for vaccination were excluded to ensure the study is not biased. 238 parents were included in the study. Each parent was interviewed separately and asked a couple of questions based on a predetermined questionnaire.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of responses using absolute frequencies with percentages (categorical variables). The association between vaccine hesitancy and exposure variables was also evaluated. Exposure variables measured as on a 1 - 5 points scale were analyses excluding respondents who did not express an opinion and pooling them in two categories (e.g. strongly agree and agree or disagree and strongly disagree). Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between hesitancy and socio-demographic characteristics of parent’s distribution. Adjusted odds ratio ORs and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals 95% CI were used to describe the strength of association. Results were considered only when P value < 0.01.

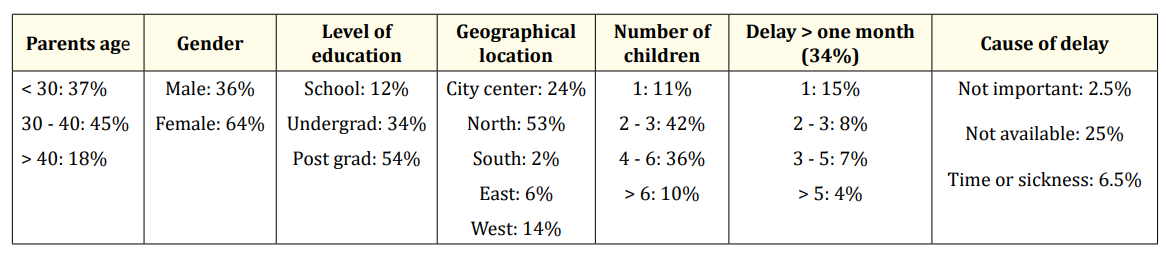

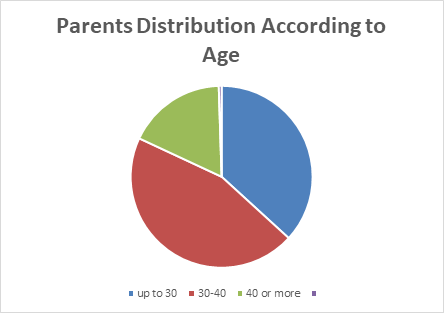

Parents’ Age, Gender and Number of Children: 238 parents participated in the study.84 male (35%), and 154 females (65%). 88 parents (37%) were younger than 30 years. 108 parents (45%) were between (30 - 40 years). And 42 parents (18%) aged more than 40 years (Figure 2).

26 parents (11%) had only one child. 101 parents (42%) had 2 or 3 children. 86 parents (36%) had 4 to 6 children. 25 parents (10%) had more than 6 children.

Educational level of participating parents: 129 parents (54%) had postgraduate education, while 81parents (34%) completed undergraduate studies. Completion of pre-university level of education was found in 28 patients (12%)

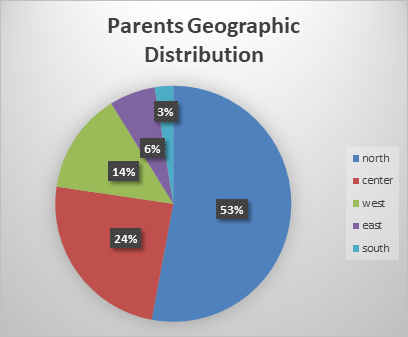

Epidemiological distribution: 126 parents (53%) were living in the Northern neighborhoods of Riyadh, 58 parents (24%) in the Center, 33 parents (14%) in the West, 15 parents (6%) in the East, and 6 parents (2%) in the Southern areas.

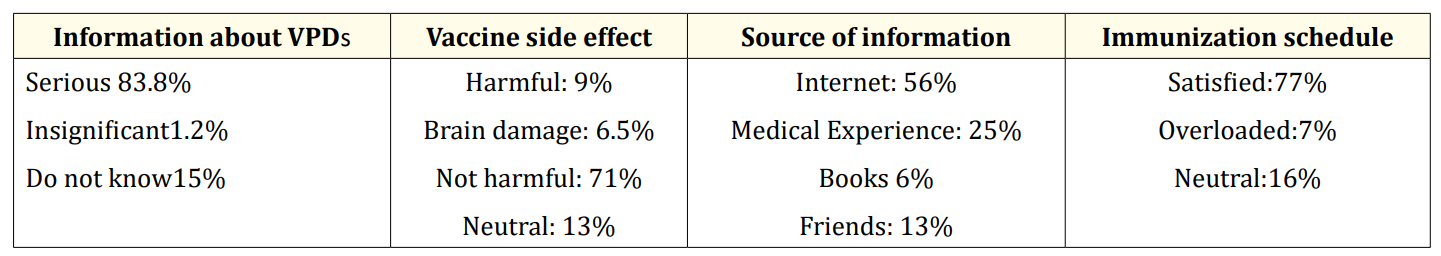

Parents’ information about Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs): 47 parents (19.8%) strongly agree, and 152 parents (64%) agree that vaccines are essential for the health of their children to protect them from serious untreatable VPDs. 3 parents (1.2%) disagree and think that VPDs are transient and are not serious. 36 parents (15%) were neutral or did not know

Vaccine safety and possible side effects: Regarding vaccine safety, 21 parents (9%) thought vaccines could be harmful to child health. 16 parents (6.5%) think that vaccine could damage the brain. 170 parents (71%) consider vaccines entirely safe. 30 parents (13%) felt neutral about that.

Acceptance of the MOH vaccine schedule: 16 parents (7%) found it overloading. 39 parents (16%) felt neutral or selected do not know. 183 parents (77%) were satisfied with the vaccination schedule.

Source of information on vaccines: The main source of information on vaccines was the internet and social media for 134 parents (56%), personal experience and contact with medical staff in 59 parents - 25%), friends and relatives for 31 parents (13%) and books for only 14 parents (6%).

Vaccine delay, or dropping: 81 parents (34%) confirmed that at least one of their children had considerable delay in vaccination for more than one month. 60 parents (25%) attributed that to unavailability of vaccines. 6 parents (2.5%) delayed vaccines because they believe they were not important. 15 parents (6.5%) delayed vaccines due to child’s sickness or time constraints.

126 parents (53%) from the Northern neighborhoods of Riyadh, 58 parents (24%) from the city center, 33 parents (14%) from the west, 15 parents (6%) from the east, and 6 parents (2%)from the southern areas.

Table 1: Parent’s Demographics

Table 2: Parents’ Knowledge.

Figure 2: Lymphocyte response in PEM on dahi and milk in diet.

Figure 3: Geographical distribution

81 parents (34%) confirmed some delay in at least one vaccine for one of their children for more than one month. 60 parents (25%) due to unavailability of vaccines. 6 parents (2.5%) delayed vaccines because they believe it is not important. 15 parents (6.5%) because of sickness or they have no time. this means that only 2.5% of parents had delayed or dropped vaccines intentionally.

Compared with other developed or developing countries, seems much less than US, Australia, UK, and France as stated in the introduction.

Data analysis for 37 parents (15.5%) who have misinformation showed that 31 parents (85%) aged (30 - 40). 31 parents (85%) of them were female. 37parents (100%) of them of high education level “post graduate”. All live in the northern neighborhoods of Riyadh. All (100%) mentioned social media and the internet as their main source of information.

16 parents (6.5%) mentioned that vaccine may harm the brain. All of them aged (30 - 40). 15 parents (94%) of them are female. 15 parents (94%) of them live in the north. all of post graduate level. All find social media and the internet their main source of information.

52 parents (22%) when asked about vaccine possible risk were neutral. 36 parents (70%) aged (30 - 40). 16 parents (31%) less than 30. 34 parents (65%) are postgraduate. 18 parents (35%) parents were undergraduate.

40 (77%) parents live in the north of Riyadh. 38 (73%) parents said that social media is the main source of information. 13 (25%) parents mentioned friends and relatives the source of information.

Some common factors seem shared between members of all the hesitant groups. Fortunately, the vast majority still give vaccines to their children in spite of their misinformation background or their hidden concerns. However, it is those hesitant parents who stand in-between and need our future approach and help to protect them from the anti-vaccine movements. Health authorities and academic institutions must work together to know characters of these groups, define them, and put the suitable procedures to explore their concerns and correct their misinformation. Ignorance of these groups which seems growing significantly worldwide may push them to the delay/drop group as what happened in the UK in the 90s or in Italy recently.

Many shared features can be seen of the risky parents in our study:

This given model seems very similar to that of the developed world (parents of the wealthy areas, from the middle age group not very young parents, very well educated, some of them are medical staff or university doctors, active on the internet and social media pages.

This parent model seems completely different from that in the developing countries and many countries of Asia.

Table 3: Common factors between the Risky Group Members..

According to the definition of VH 15.5% of parents has shown some degree HV spectrum. However, the very minority only (2.5%) who delayed or dropped vaccines intentionally. Compared with countries like Australia (25%), USA (13.5%), UK (25.3%), France (41%) and Italy (15.6%) the situation here seems better [6,9,11,12].

Growing numbers of cautious acceptance and acceptance with misinformation seems alarming and needs early practical interventions.

Unavailability of vaccines due to shortages in vaccines and vaccine out of stock in hospitals and medical centers caused the vast majority of vaccine delay (74%) of cases.

15.5% of parents has shown some degree of VH spectrum. However, minority (2.5%) only who delayed or dropped vaccines intentionally. Misinformation and concerns about vaccine safety did not affect parents’ decision to vaccinate their children yet. However growing number of cautious acceptance and acceptance with misinformation seems alarming and needs early practical interventions. Social media and the internet is the main source of information for the majority of parents and for almost all the hesitant group. Higher educational level, living in wealthier neighborhoods, female gender, and middle age group are risk factors for vaccine hesitancy here. Most young parents still accept vaccines as ordinary. All parents accept the recommended vaccination schedule, few parents think that it is overloaded. Considerable number of parents did not know VPDs morbidity and mortality.

Unavailability of vaccines is the most common cause of vaccine delay.

This study discloses that the national vaccination target of 95% to achieve herd immunity has been achieved in Riyadh. However more similar research studies in other parts of the city and also other cities are necessary. Such essential national health screening evaluations should be repeated on regular bases to address harmful changes in parents’ attitude spectrum early. Better efforts seem mandatory to avoid shortage in vaccines and vaccine out of stock incidents. A hesitant parent will hesitate twice before catch up of vaccines. Urgent prophylactic interventions at the moment for parents of the hesitant groups seem necessary to address their concerns and correct their misinformation. These interventions should be tailored mainly for mothers and grandmothers of the middle age group, living in the northern wealthier neighborhoods of Riyadh and with high level of education. It seems that Young parents still consider vaccines ordinary and accepted, but we have to consider the strong family relationship here. One misinformed trusted grandmother may change the attitude of all her related younger parents. Social media and internet pages should be screened by authorities and all harmful websites should be strictly band. It seems that specific pages should be established on the website of every hospital and every small medical center or even a small pediatric or family private or public clinic. these pages should be attractive with simple medical vocabulary. All the rumors about vaccines should be argued and justified very clearly. We must use the same weapons against the antivaxxers, their background, political loyalty, real academic achievements, and restrictions on practice all should be disclosed for the public. Possibility of comments, feedback, and communication also should be offered and directed by trained professionals. All young parents with each delivery should be educated clearly and frankly before discharge about the real morbidity and mortality of (VPD)s vaccine preventable disease. For them it is something from the past. They need to feel the difference between the natural disease history of complications and the luxury of vaccine era. Vaccination is a national health necessity not a personal decision. Once we accept to live within a given society we must harness our behavior for the best interest of all. This is the border between freedom and complete miss.

Copyright: © 2018 : Gihad Al-Saeed., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.