Sreejit Ghosh1,2, Subhashis Sahu1* and Goutam Paul1

1University of Kalyani, Department of Physiology, Nadia-741235, West Bengal, India

2Department of Physiology, Jhargram Raj College, Jhargram-721507, West Bengal,

India

*Corresponding Author: Subhashis Sahu, University of Kalyani, Department of Physiology, Nadia-741235, West Bengal, India.

Received: June 13, 2024; Published: August 22, 2024

Citation: Subhashis Sahu., et al. “A Narrative on the Impact of Caloric Restriction on Ageing-Induced Changes in Cognitive Function: Correlating Brain GABAergic and Glutamatergic Profile". Acta Scientific Nutritional Health 8.9 (2024): 45-54.

A dose-response model called hormesis shows how minor environmental stress can have positive consequences. Studying animal models, Caloric Restriction (CR) has been proven to improve toxin-resistance and to lessen ischemic brain and cardiac injury, autoimmune disease and hypersensitivity. CR limits the overall amount of daily food intake and is used as a means for relieving ageinginduced incapabilities. Mild dietary stress enhances cellular resistance to stress, lengthening lifespan and reduce morbidity. Fasting, which can be considered as a form of environmental stimulus is known to result in elevated HDL and apoA1 levels which ultimately provide benefit to the cardiovascular system. Keeping in view the multidimensional benefit of practicing CR diet, the present review focuses on its positive impact in amelioration of ageing-induced deficits in brain functions highlighting the functional dynamics in the CNS. In mammals GABA-glutamate homeostasis is central in maintenance of higher brain functions including cognition which is believed to be perturbed during ageing. The down-regulation of regional GABA-glutamatergic homeostasis induced by ageing process is either prevented or at least delayed by CR diet which restores cognitive functions especially memory function. Thus the ageing population gets out of their dependency either from the family or the state provided health infrastructure. The society ultimately benefits having an interactive ageing population quite able to drive the young generation with their experiences. Finally, a dearth of data on the efficacy of CR in clinical set up needs more work in similar area.

Keywords: Caloric Restriction; Hormesis; Cognition; Lifespan; Glutamate; GABA

Ageing is often described as chronological age, with a 60-65 year old cutoff. The retirement age and this cutoff age are comparable, which contributes to this definition [1,2]. In these situations, the socially created meanings of age such as the responsibilities that are allocated to the elderly or the loss of particular functions that denote a physical decline in old age are more frequently relevant [3]. The population over 60 makes up around 11.5% of the world’s population of 7 billion people [4]. This percentage is expected to rise to almost 22% by 2050 when the elderly will surpass the number of youngsters under the age of 15 [4,5]. While the working and kid age groups steadily decline, the old age group is the one that is expanding the quickest [6,7]. In recent times, the proportion of old people in India has been rising, and this tendency is probably going to continue in the upcoming decades [8].

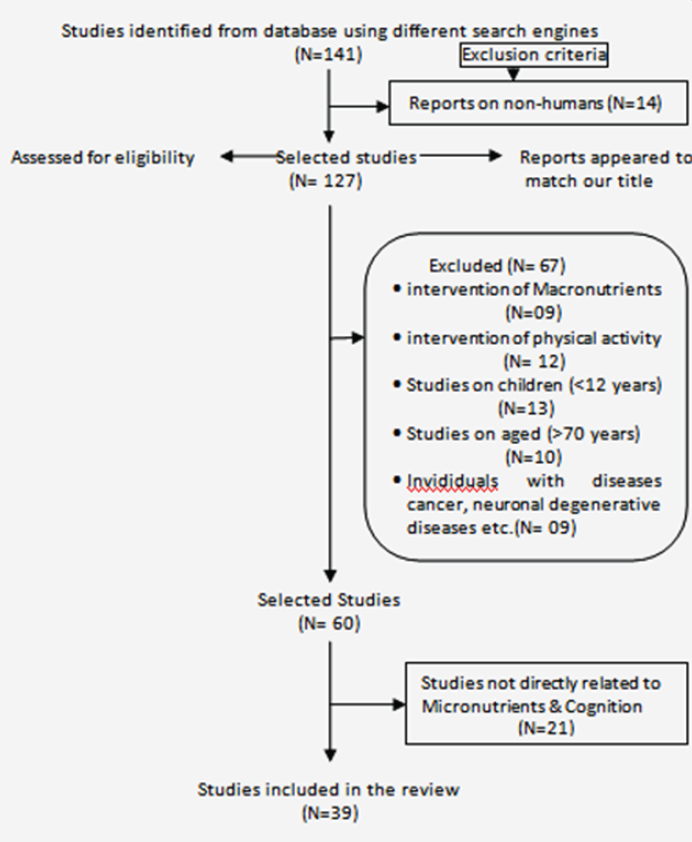

The search was carried out during the months of June to September 2023, using the electronic database PubMed (MeSH), PubMed Central, Sage Journals, Science Direct, StatPearls (Internet), ResearchGate, Frontiers, Semantic Scholar, research, MDPI and Academia.edu. We identified 155 studies initially. We decided not to exclude much earlier studies and simultaneously emphasized on recent publications. The idea behind such selection was to make the picture longitudinally visible. We always had in mind that the review is being written to synthesize a story from piecemeal information scattered through years. Searching was done using single keyword as well as in combination. Major keywords include Caloric Restriction, Hormesis, Cognition, Lifespan, Environmental stimulus, memory and learning. Combined searching included two, three or even four keywords put in a sentence form. Initial exclusion criteria included reports on humans with pre-existing neurodegenerative diseases (N = 24), intervention of Macronutrients (N = 11), and Physical activity (N = 12). Studies on children (<12 years; N = 13) and individuals with pre-existing non-neuronal diseases (cancer, lupus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pancreatitis etc.; N = 19). Reviews and original research articles except duplicate articles were selected for analysis and synthesis. Upon screening of the articles 59 manuscripts were selected for the purpose of the study. Inclusion and exclusion of manuscripts based on above mentioned criteria have been visually presented in figure 1.

Figure 1: Methodological flowchart.

Cognition is a brain function. Consciousness is closely related to working memory, mental imagery, willed action, and higher cognitive abilities. All of these processes have one thing in common: they all involve information being "held in mind" for a while. This data can be created for the future or obtained from the past, and it may contain information on stimuli or responses. According to research on brain imaging, "holding something in mind" is linked to activity in an extensive system that includes the prefrontal cortex as well as more posterior regions, the precise position of which depends on the type of information being retained [9]. The hippocampus is another structure that is thought to be essential to human cognition [10-12]. Apart from its well recognized function in memory, the hippocampal structure is also involved in executive function, intellect, processing speed, path integration and spatial processing [13-15]. It has been demonstrated that, in the absence of neurological damage or neurodegenerative disorders, each of these cognitive processes ages cognitively [16]. Memory changes are among the most prevalent cognitive problems among the elderly-population. In fact, on a number of learning and memory tests, older persons do not do as well as younger adults combined. Slow processing speed [17], a diminished capacity to filter out unnecessary information [18], and a decreased application of learning and memory enhancing techniques [19] are all potential causes of age-related memory alterations.

For millennia, the combination of food and other lifestyle factors, such physical activity, has significantly influenced mental ability and the development of the brain [20]. The fact that eating is an ingrained human habit highlights the ability of dietary elements to influence mental health on both an individual and a population-wide basis [20]. Compared to the rest of the body, the brain uses a tremendous amount of energy [20]. Therefore, it is probable that the systems governing the transport of energy from food to neurons are crucial to the regulation of brain activity. Therefore food, nutrient, energy and life are synonyms in the context of maintenance and propagation of life on the planet “Earth” because they all individually is part of an eternal physical system that continues irrespective of the existence of life.

Table 1: Studies on the ageing process and age-related cognitive decline.

For millennia, the combination of food and other lifestyle factors, such physical activity, has significantly influenced mental ability and the development of the brain [20]. The fact that eating is an ingrained human habit highlights the ability of dietary elements to influence mental health on both an individual and a population-wide basis [20]. Compared to the rest of the body, the brain uses a tremendous amount of energy [20]. Therefore, it is probable that the systems governing the transport of energy from food to neurons are crucial to the regulation of brain activity. Therefore food, nutrient, energy and life are synonyms in the context of maintenance and propagation of life on the planet “Earth” because they all individually is part of an eternal physical system that continues irrespective of the existence of life.

Epidemiologists recognized the ‘Hara hachi bun me’ practice by the habitats of Okinawa island of Japan as central to their elevated average longevity and comorbidity-free living [21]. The practice consists of modifying the food intake pattern that had long been passed on to generations of Okinawa residents. People, irrespective of age consume eighty percent to satiety and that is a life-long practice. The epidemiological study attracted researchers from various fields of life sciences to propose a hypothesis linking the habit of calorie restricted food intake with longevity and physical and mental health. To perceive cellular energy production as the solitary function of food implies undermining its role in the body unless prevention of and protection from diseases are accepted other important functions as well [22]. Several epidemiologists reasonably view the ‘Okinawa concept’ in the light of ‘Thrifty gene hypothesis’, an approach of making the most out of minimum resources and they believe that the existence of an apparent rule that ensure survival in the midst of scarcity is a natural phenomenon [23]. On the other hand, recognition of certain major deficiency diseases such as scurvy, rickets, beriberi, and xerophthalmia which could be cured by types of foods [24] justifies the preventive role of food. The historical background of dietary modification sequesters an essence of motivation for the young researchers to predict relationship of calorie intake with physiological parameters determining physical and mental health. The work which was initiated by McCay in 1935 [25] almost 85 years ago in search of the effect of calorie restriction, a non-genetic intervention, on life span in mammals including mice, rats, and most nonhuman primates is still being researched by the present workers [26] to reach a conclusion. Series of works by several stalwarts in the field during a span of eight years (2000 to 2007) provided evidence on definite role of calorie restriction, in any form, on life and the effects observed were all positive to life [27]. Based on neuroprotective data of CR in relation to brain aging (Ingram, 2009) and protection against neurodegenerative diseases [28], the objective of the present review is to look for impact of CR on aging brain health in the available laboratory environment using rat model with special reference to brain glutamatergic activity profile [29]. Caloric Restriction is basically a stimulus which drives the body systems to arouse and adapt. The stimulus might act as initiator of a chain reactions terminating to a net and new adaptive mode. ‘Hormesis’ is the term that explains dose-response phenomenon, in the present context how the body system handles the CR stress.

Hormesis is a time-tested phenomenon which is fundamental and very common in biological sciences for its use as a dose-response model [30]. The phenomenon of hormesis describes that mild environmental stress may create beneficial effects with certain compensatory changes [31]. Low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition are the features of hormesis which leads to adaptive responses/changes in organisms [32]. The toxic stimuli discussed in the context of hormesis not necessarily originate from toxic substances but may also arise from any environmental conditions which appear potentially harmful for the organism, viz. steep rise or fall in ambient temperature. Any stimulus will be called mild stress if it ends with beneficial hormetic response [31]. The actual benefit of mild stress lies in slight increase in lifespan and increase in the power of resisting certain additional stress as well [33]. Caloric restriction (CR) is a type of mild dietary stress which can be easily modulated. Such mild stresses, not to the extent of malnutrition, delay a number of ageing-induced physiological changes and have been concomitantly found to extend mean lifespan of laboratory animals [34,35]. Report of McCay in 1935 in rodents in support of the above statement is viewed to be pioneering. Since then, a significant number of researchers started justifying the observations of McCay since then in various species which include fishes [36], flies [37], worms [38] and yeast [39]. The finding of Colman in 2009 regarding extended lifespan and increased resistance against diseases in primates following CR attracted the scientist community. Subsequently it was reported that CR may increase lifespan in humans as well [40]. Animal experiments under long-term CR have demonstrated the beneficial role of CR in preventing or ameliorating the severity of neoplasia that develops spontaneously, chemically, or radiationally in experimental mice [41,42]. Chronic CR has been reported to successfully contribute in the reduction of ischemic brain [43] and cardiac injury [44]. CR has further been reported to inhibit certain mouse strains [45], the development of autoimmune illness is delayed, and the beginning of allergic dermatitis whether unconstrained [46] or chemically induced [47]. CR potentially augments toxin-resistance in probing animals which is highly pertinent to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases [48]. Beneficial effects of CR so far discussed are likely to be mediated at least in part, if not otherwise, by hormetic mechanisms [49].

Table 2: Studies on hormesis and caloric restriction and their influence on the ageing process.

Caloric restriction (CR) follows various regimens when applied to experimental animals. For example, restriction of chronic energy intake involves rationing of total calorie intake in 24-hour using defined diets [41,50]; this is referred to as caloric restriction (CR). Restriction in total daily nutrient intake is characteristic of long-term total-nutrient restriction [51]. Total nutrient restriction permits experimental animals to eat between 60% and 80% of what animals given ad libitum (AL) ingest [46]. Animals are typically fed once daily throughout experimental treatments. CR animals typically consume the whole quantity given in within an hour, then fast for the following 23 hours in accordance with procedure [52]. Intermittent fasting aka alternate-day fasting is another form of CR in which animals are fed ad libitum following a day of fasting [53]. It has been observed that mice under alternate day fasting consume roughly twice the amount of mice fed AL on days when they can get food [54]. Further, it is highly contextual that mice under alternate-day fasting maintain the same body weight to those of AL-fed mice [54]. The observation reveals that alternate-day fasting does not imply diminution in the amount of food consumption rather, limitation in the frequency of food intake. CR having shorter duration has also been found effective against environmental stress as evident from the works of Raffaghello and Nakamura. They have observed that two days of water-only fasting have differential responses against oxidative stress in mice [55] while, represses chemically caused allergy in mice [56].

Various reports have confirmed that mild dietary stress potentiates cellular resistance to stress be it environmental or indigenous and such potentiating of cellular resistance ultimately increase lifespan in one hand and on the other hand, protect different kinds of morbidity [49]. So far the hormetic mechanisms are concerned CR has been reported to result in an up regulation in SIRT1 mRNA expression [57]. It is known that SIRT1 is one of the key regulators in many cellular defenses against stress [58]. In yeast CR-induced increase in longevity is associated with the activation of Sir2P which is actually a homologue of mammalian SIRT1 [40]. In non-obese humans three weeklong intermittent fasting has been found to result in the increase in expression of SIRT1 [59]. CR-induced augmentation in the expression of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) is considered another beneficial effect of mild stress [50]. HSPs in the cellular environment basically serve as chaperones and are essential in defending cells from stress. The classifications of HSPs are made on the basis of their molecular weight (e.g., HSP10, HSP60, HSP70 and HSP90) [60]. CR in rat model has been found to undo the age-dependent reduction in the HSP70 transcription factor expression in hepatocytes [61]; whereas, intermittent fasting results in an increase in the level of HSP70 protein in cortical synaptosomes [62]. Hipkiss et al. pointed out that insistent glycolysis is injurious due to the formation of methylglyoxal [63]. Methylglyoxal causes mitochondrial damage by rapid glycation of proteins and it is formed from glycolytic intermediates. Daily restricted animals depend on glycolysis for initial 12 hours following feeding and subsequently get energy through mobilization of fat during next 12 hours [52], when glycolysis remains suppressed [64]. Hipkiss highlighted the event of suppression of glycolysis as the beneficial effects of CR.

That dietary restrictions have potential role in disease protection in laboratory animals is well evident from a bunch of observations. CR has been reported to ameliorate the severity of a number of diseases and even in some cases it shows a preventive role. A few examples of these conditions are cancer [41], stroke and CHD [44,65], autoimmune illness [45], hypersensitivity [47], PD and AD [48]. Yet there is a significant deficiency of information related to the effectiveness of CR in clinical therapy. Again on the other side, CR is positively correlated in prevention of obesity while obesity in humans is known to invite various morbidities such as CHD, cancer, atherosclerosis, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Epidemiological studies have reported reduced risk for Parkinson’s disease with daily low calorie intake [66] and so is Alzheimer’s disease [67]. The outcomes using animal models are congruent with the epidemiological studies on Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. In another study, Story had described a possible relationship between asthma and obesity [68], while studies in a clinical setup have shown that low-energy diet consumption significantly reduced inflammation and oxidative damage in atopic dermatitis patients [69]. In a number of studies, alternate day fasting have shown satisfactory results in patients with inflammatory diseases [70,71]. The beneficial effects of CR on allergic diseases are inspiring for the consistent results in animal studies [46]. Effectiveness of fasting [72] and low-energy diet [73] in the treatment of Rheumatoid arthritis have been demonstrated. The beneficial effects of dietary modulation on autoimmune disease have been found to be consistent in animal models [45]. However, based on the present information and knowledge a number of well-designed randomized controlled studies may unveil more mysteries of treating diseases through modulation of diet for ultimate benefit of humankind.

The mammalian brain (pre-frontal cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus and pons-medulla) have higher levels of the glutamate neurotransmitter than other regions of the central nervous system [74]. In higher brain activity, the excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA cooperate to maintain this equilibrium [75]. The primary players in this process [76] are succinate, glutamine, GABA transporters, glutamate decarboxylase and GABA transaminase [77]. The downregulation of regional GABA-glutamatergic homeostasis induced by ageing process [78] has been shown to be prevented, postponed, or even significantly ameliorated by consuming a low-calorie, high-nutrient diversity diet [79]. This suggests that the CR diet may benefit the population's cognitive protection across all age groups by manipulating the central neurotransmitters in a desired direction

Table 3: Studies on caloric restriction and its effects on brain regional GABA-Glutamate system.

It's common to see old age as a period of relaxation, introspection, and opportunity to take care of tasks that were postponed while pursuing jobs and having families. Regretfully, growing older is not always a happy experience. An ageing person's mental health can be severely impacted by late-life events such as the death of friends and loved ones, chronic and incapacitating physical conditions, and the inability to engage in once-loved hobbies. In addition to bodily changes like hearing loss, deteriorating eyesight, and other physical changes, an older adult may also feel as though they have less control over their lives owing to outside influences like scarce financial resources. Adverse feelings like depression, anxiety, loneliness, and poor self-esteem are frequently brought on by these and other problems, which in turn lead to social withdrawal and apathy. The time-tested observations and experiences of researchers in the domain of ageing-associated deterioration of neural functions witness the role of malnutrition and over-eating on ageing-related health outcome. There are enormous work-reports in this area of research, yet they are not free from contradictions. This is why the area of modulation of diet for a positive health outcome is still vibrant in colors as a hot area of research and the necessity simply lies in making the area free of controversy. The present review makes an approach to pinpoint the ageing-induced cognitive decline and the correlated social problems. At the same time the review intends to find an avenue for protection/amelioration of such cognitive deficit by manipulating modes of dietary intake, both in terms of frequency as well as quantity. In brief, the focus of the present review is to find out a novel and unique lifestyle to ensure a healthy living at all ages and more so during senescence. This will not only provide financial safeguards to the governments to provide public health services at the same time the society shall get more productive aged citizens who are free from depression and able to participate in social activities. Participation in social activities shall in turn protect from aging-induced cognitive decline and the bidirectional crosstalk between depression and cognition will not surface.

Copyright: © 2024 Subhashis Sahu., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.