Vibhuti Sharma, Gaytri Mahajan and Reena Gupta*

Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Summerhill, Shimla, India

*Corresponding Author: Reena Gupta, Professor, Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Summerhill, Shimla, India.

Received: July 15, 2024; Published: August 28, 2024

Citation: Reena Gupta., et al. “Exploring the Phytochemistry and Antimicrobial Effects of Moringa oleifera on Waterborne Bacteria". Acta Scientific Microbiology 7.9 (2024):42-50.

Graphical Abstract

Many developing countries are facing severe health issues due to invasion of harmful bacteria. The microorganisms that enter into the mouth by the means of feaco-oral route, are causing mortality among children. Moreover, it is estimated that inadequate sanitation, contaminated water, or a shortage of water account for as much as 80% of all diseases and illnesses worldwide. Plants are abundant in secondary metabolites and are employed in the indigenous medical system to treat a variety of diseases. It has been discovered that the parts of the plant of Moringa oleifera have amazing ability for enhancing quality of water due to the presence of various phytochemicals in them. In present study, the qualitative analyses of phytochemicals present in Moringa seed and leaf extracts was carried out and the extracts were tested for their anti-bacterial activity against various pathogens associated with water-borne diseases. The results acquired from this research revealed that the seeds and leaves of Moringa possesses anti-bacterial activity. Therefore, this study looks into the water purifying potential of Moringa oleifera as well as its role against a number of bacterial pathogens.

Keywords: Moringa oleifera; Phytochemicals; Bacterial; Pathogens; Anti-bacterial

oleifera: Moringa oleifera; E. coli: Escherichia coli; S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus; NCCLS: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards

The word 'infection' refers to the replication of pathogenic microorganisms in the body of host [2]. Infections like diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid are the most common infections among the population of developing countries which usually occurs due to the ingestion of contaminated food or water [1]. Around the world, a large portion of the population lives in developing nations with poor access to clean drinking water [3]. Microbial contamination of water occurs when animal or human sewage contaminates source water that has not been appropriately treated via filtration, chlorination or other means. In underdeveloped nations, diarrhoea has been linked to almost six million infant deaths annually [4]. Population growth and increased industrialization cause the waterborne infections, one of the problems caused by groundwater contamination [5]. Among various enteric pathogens, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus are causal agents of various types of infections [6,7]. The resistance to these bacteria for antibiotics and capacity to build biofilms make the treatment challenging. The inappropriate discharge of untreated effluents from industries, directly into agricultural areas and various water bodies is one of the most important causes of groundwater pollution [8]. Heavy metal buildup in the food chain is ultimately a result of untreated industrial effluents [9]. This information is of great significance to many nations, which has promoted the creation of alternative and practical approaches or technologies to deal with the problem of supply of safe water [10].

Moringa oleifera, also known as ‘horseradish tree’, is a rapidly emerging and abundantly planted tree in India. Due to abundance of bioactive chemicals found in the Moringa plant, every component has been linked to several health and nutritional advantages [11]. Numerous pharmacological characteristics, such as anti-inflammatory, antihypertensive, analgesic, anticancer and antioxidant capabilities, have been supported by prior scientific studies [12,13]. Along with the advantages of nutrition for health and therapeutic value, this plant has been identified as a coagulant in purification of water, having no adverse effects on health, even at significantly higher dosages [14]. Due to the high concentration of bioactive substances found in Moringa oleifera, including tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, polyphenols, isothiocyanates, carotenoids and saponins, the seeds and leaves have also demonstrated notable pharmacological capabilities [15]. Moringa oleifera inhibits the growth of different pathogens [16]. In this study, the anti-bacterial activity of seed and leaf extracts of Moringa oleifera was checked on waterborne bacteria.

All of the chemicals employed in this study were obtained from Merck and Hi-Media in Mumbai, India; Sigma-Aldrich in Steinheim, Germany; Sigma Chemicals Co. in the United States of America. Every compound was utilized precisely as supplied and was of excellent analytical quality.

The seeds (along with their seed coat) and leaves of Moringa oleifera plant were collected from the Herbal Garden Neri, Hamirpur (H.P.). After collection, the seeds and leaves of Moringa oleifera were pretreated with 5 % sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, followed by soaking in distilled water for 2 min. The seeds and leaves were then kept for drying and further grounded into fine powder.

The clinical isolates (Escherichia coli MTCC No. 46 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC No. 87) were procured from the Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Summer hill, Shimla.

The powdered sample of seeds and leaves of plant was extracted with n-hexane, petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, ethanol, distilled water, methanol and acetone using maceration. In this procedure, 20 g of seed and leaf powder was soaked separately in 200 mL of each of the solvent. They were kept at 37°C at shaking for 3 days to allow the release of active molecules. The extracts were then separated and filtered using Whatman no.1 filter paper. The supernatant of each extract was then kept for evaporation. Further, the extracts were stored at 4°C.

Different qualitative tests were performed to check the presence of various phytochemicals in extracts.

A few drops of 0.1% ferric chloride solution were added to 1 mL of seed and leaf extracts. The formation of blue-black precipitates specified the presence of tannins.

A mixture of 1 mL of concentrated H2SO4 and 2 mL of ammonia solution was prepared using 1 mL of each extract. The emergence of a yellow colour indicated the presence of flavonoids.

2 mL of Mayor's reagent was put into 1 mL of each extract. The production of brown or yellow precipitates specified the presence of alkaloids.

Each extract was diluted with 1-2 mL of distilled water, vigorously stirred, and observed for the continuous formation of honey comb foam.

To 2 mL of anhydrous chloroform, 1 mL of each extract was dissolved. The solution was then thoroughly mixed with concentrated H2SO4. Steroids were detected by the creation of a reddish-brown colour ring at interface.

A mixture of 1 mL of each extract, 2 mL of concentrated H2SO4, and 1 mL of chloroform was prepared. Terpenoids were present at the interface where a reddish-brown colour appeared.

Anti-bacterial activity of seed and leaf solvent extracts od Moringa oleifera was tested against Escherichia coli MTCC No. 46 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC No. 87 by agar well diffusion method according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). Escherichia coli MTCC No. 46 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC No. 87 bacterial cultures were spread on agar plates. After the plates had fully dried, six-millimetres wells punchout were made on agar medium and various volumes (20, 30, 40, and 50 µL) of leaf and seed extracts were added to distinct wells. The respective solvents were utilized as negative controls, while the antibiotic (tetracycline) served as positive control. The plates were then incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Following incubation, the zone of inhibition was measured and compared.

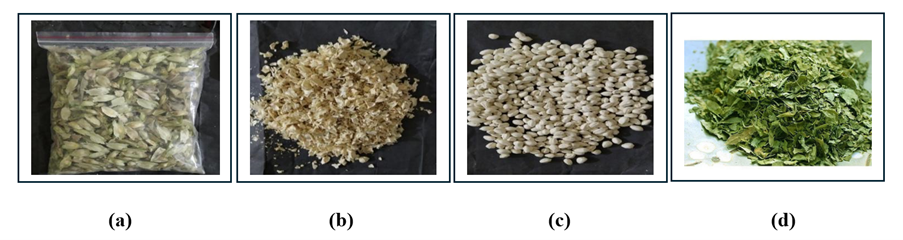

The seeds and leaves of Moringa oleifera which were shade dried are shown in Figure 1 (a-d). After complete drying, they were converted into fine powder.

Figure 1: (a) Seeds of Moringa oleifera inside the seed coat (b) Coat of Moringa oleifera seeds (c) Seeds of Moringa oleifera without seed coat and (d) Leaves of Moringa oleifera

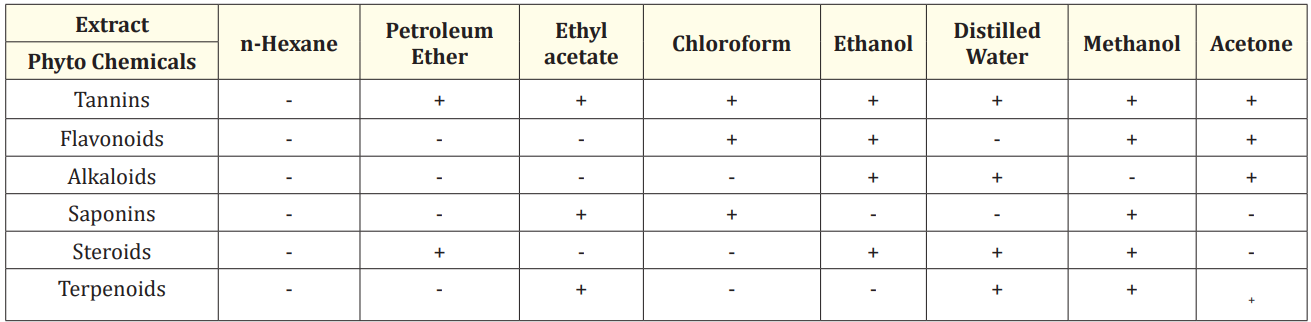

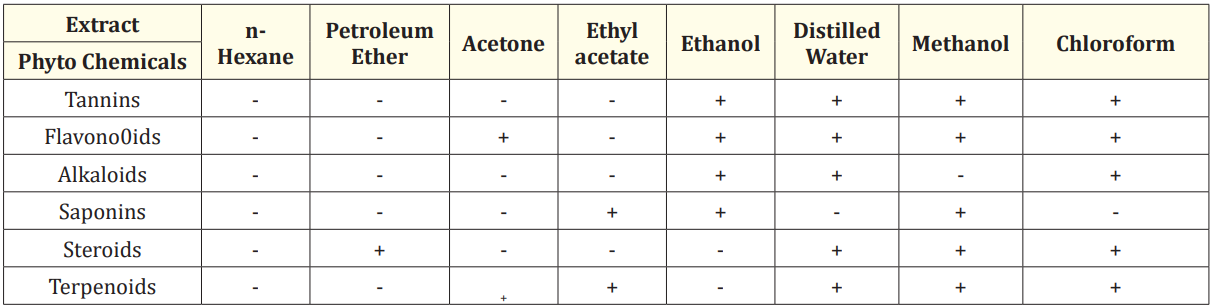

The results of phytochemical analysis of solvent extracts of seed and leaf are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively.

Table 1: The phytochemical examination of solvent-extracted Moringa oleifera seed extracts.

Table 2: The preliminary phytochemical analysis of different solvent extracts of Moringa oleifera leaves.

The ethanol, distilled water, methanol and acetone extracts of Moringa seed powder indicated the presence of the greatest number of phytochemicals (Table 1). The ethanolic extract indicated the existence of tannins, alkaloids, flavonoids and steroids. Tannins, alkaloids, steroids and terpenoids were present in distilled water extract. All phytochemicals except alkaloids were present in the methanolic extract, with the exception of alkaloids. Alkaloids, flavonoids and tannins were detected in the acetone extract. The distilled water extract of seed indicated the existence of alkaloids, saponins and tannins [17]. According to research in the literature, alkaloids and flavonoids are bioactive compounds present in medicinal plants—have potent antibacterial properties [18-20]. Phytochemical constituents are responsible for pharmaceutical and hazardous effects in plants, according to various studies [21-23].

Therefore, the existence of various metabolites in seed extracts of Moringa oleifera probably make it an effective antibacterial substance.

The ethanol, distilled water, methanol and chloroform extracts of leaves indicated the presence of maximum number of phytochemicals. The ethanolic leaf extract indicated the presence of tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids and saponins. Tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, steroids and terpenoids were present in distilled water extract. The presence of tannins, flavonoids, saponins, steroids and terpenoids was detected in methanolic extract. The chloroform extract revealed the presence of tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, steroids and terpenoids. The present research showed the presence of the phytochemicals, which is in agreement with results obtained by previous research [24]. The findings of present study were also supported by a study which revealed that the extracts of Moringa leaves showed the presence of tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids and saponins [25].

These results showed that due to these phytochemicals, extracts of seed and leaves of Moringa oleifera exhibited strong anti-bacterial activity against various pathogens. Thus, seeds and leaves could act as potential nutrient source for animals and humans [26].

The microorganisms like Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli are present in water in very large amount. These are the major causes of various water borne diseases. The seeds and leaves of Moringa oleifera play a very important role in inhibiting the growth of these organisms.

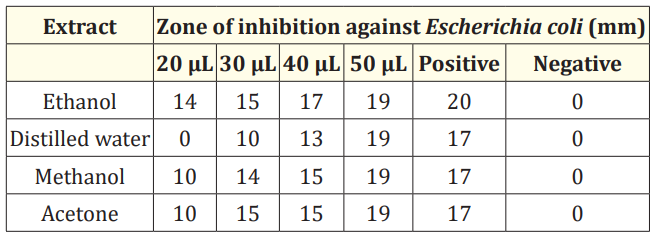

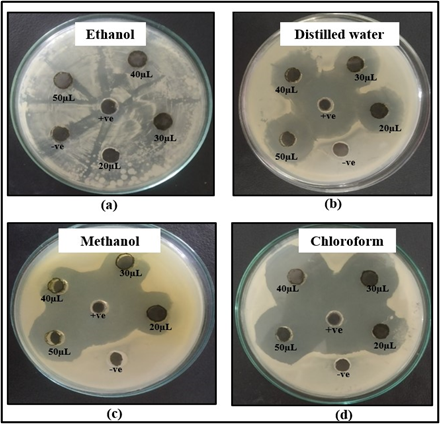

Anti-bacterial activity of seed extracts was studied using agar well diffusion assay. Tetracycline served as a positive control, while the corresponding solvents served as negative controls. All the extracts showed maximum inhibitory zone of 19 mm at volume of 50 µL against E. coli (Figure 1 a-d). The inhibitory zone of 14 mm, 15 mm, 17 mm and 19 mm respectively was shown by ethanol extract at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 2 (a). The zone of inhibition of 19 mm at volume of 50 µL but no activity was observed at 20 µL volume by distilled water extract as shown in Figure 2 (b). The methanol extract showed inhibitory zone of 10 mm, 14 mm, 15 mm and 19 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 2 (c). The acetone extract showed zone of inhibition of 10 mm, 15 mm, 15 mm and 19 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 2 (d). Our findings were confirmed by various reports on anti-bacterial activity of seed extracts of Moringa oleifera. A significant inhibitory effect against E. coli was shown by methanolic and aqueous extracts of Moringa seeds [27]. The seed ethanol extract showed the inhibitory zone of 9 mm, 12 mm and 16 mm against E. coli at volume of 100 µL, 200 µL and 400 µL respectively but water extract showed no inhibition against E. coli [28]. The acetone seed extract showed the zone of inhibition of 19 mm at volume of 50 µL against E. coli [29] which is in accordance with the present study.

Maximum zone of inhibition was shown by all four extracts at volume of 50 µL as shown in Table 3.

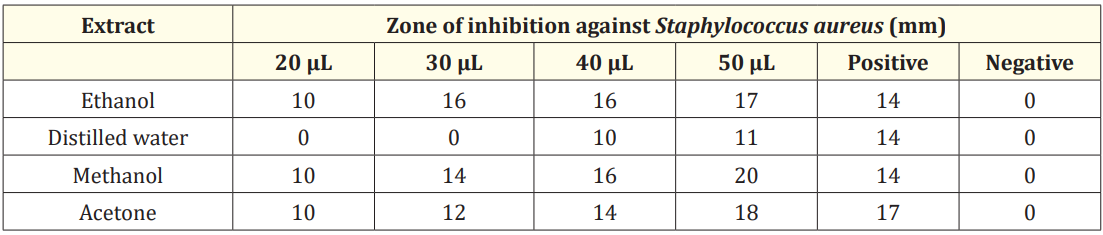

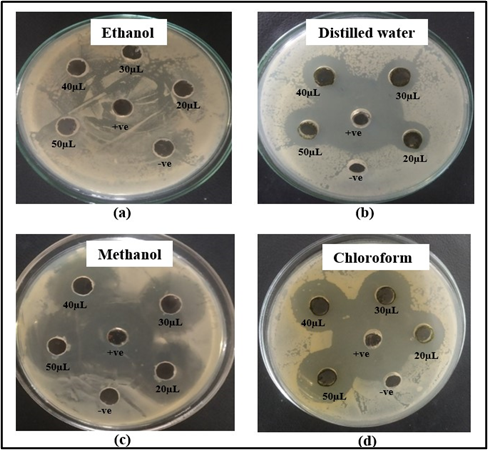

Anti-bacterial activity of seed extracts was studied against S. aureus. The ethanol extract showed inhibitory zone of 10 mm, 16 mm, 16 mm and 17 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as indicated in Figure 3 (a). The distilled water extract formed inhibitory zone of 10 mm and 11 mm at volume of 40 and 50 µL respectively but no activity was observed at 20 µL and 30 µL volume as shown in Figure 3 (b). The inhibitory zone of 10 mm, 14 mm, 16 mm and 20 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL was shown by methanol extract as indicated in Figure 3 (c). The acetone extract showed inhibition zone of 10 mm, 12 mm, 14 mm and 18 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 3 (d). In a previous study, the ethanol, distilled water and methanol seed extracts showed the zone of inhibition of 22 mm, 17 mm and 27 mm at volume of 100 µL respectively [30,31].

Figure 2: Zone of inhibition shown by (a) ethanol (b) distilled water (c) methanol and (d) acetone extracts of M. oleifera seed against E. coli.

Maximum inhibition zone of 20 mm was shown by methanol extract at volume of 50 µL. All four extracts showed maximum zone of inhibition at volume of 50 µL as shown in Figure 3 and Table 4.

Table 3: Anti-bacterial activity of extract of M. oleifera seed against Escherichia coli.

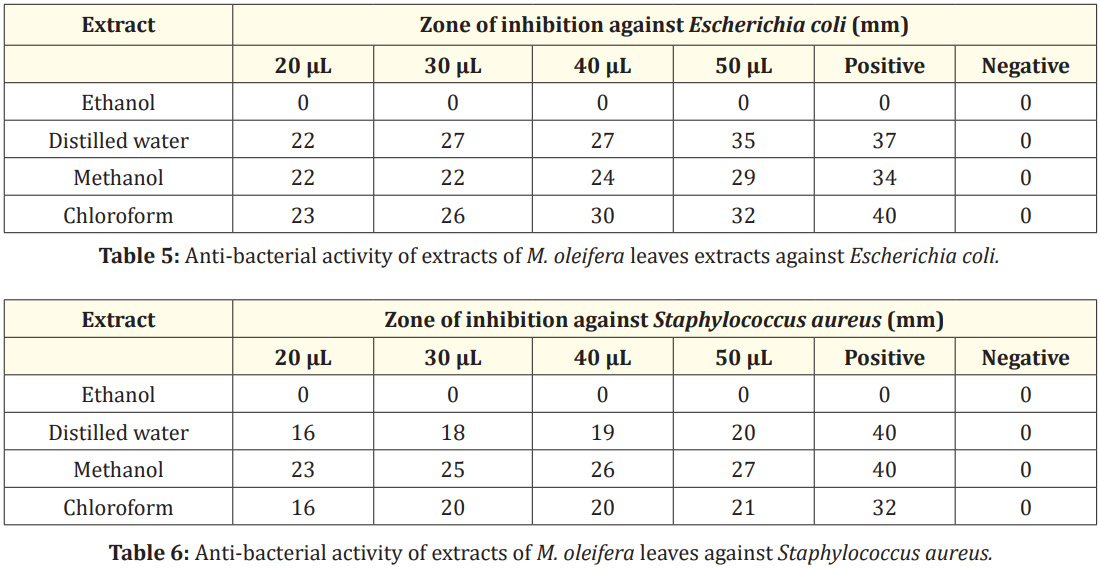

Anti-bacterial activity of leaves extracts was studied against E. coli. No inhibition of E. coli was shown by ethanol extract of leaves as shown in Figure 4 (a). The distilled water extract showed zone of inhibition of 20 mm, 27 mm, 27 mm and 35 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 4 (b). The methanol extract showed zone of inhibition of 22 mm, 22 mm, 24 mm and 29 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 4 (c). The chloroform extract showed zone of inhibition of 23 mm, 26 mm, 30 mm and 32 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 4 (d). In a recent study, ethanolic and distilled water leaf extract formed the inhibitory zone of 21 mm and 16.80 mm at 30 µL volume respectively against E. coli [32]. The methanolic leaf extract did not form inhibitory zone against E. coli and distilled water extract formed inhibitory zone of 9 mm and 10 mm at volume of 20 µL and 30 µL respectively [32]. The chloroform extract showed inhibition zone of 11 mm at 20 µL volume against E. coli [33].

Figure 3: Zone of inhibition shown by (a) ethanol (b) distilled water (c) methanol and (d) acetone extracts of M. oleifera seeds against Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 4: Anti-bacterial activity of M. oleifera seed extracts against Staphylococcus aureus

The zone of inhibition of 35 mm and 32 mm was shown by distilled water and chloroform extract of leaves at 50 µL volume as shown in Table 5.

No inhibition of S. aureus was shown by ethanol extract of leaves as shown in Figure 5 (a). The distilled water extract showed inhibitory zone of 16 mm,18 mm, 19 mm and 20 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 5 (b). The methanol extract showed inhibitory zone of 23 mm, 25 mm, 26 mm and 27 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL as shown in Figure 5 (c). The inhibitory zones of 16 mm, 20 mm, 20 mm and 21 mm respectively at volume of 20, 30, 40 and 50 µL were shown by chloroform extract as shown in Figure 5 (d). However, the ethanolic extract of M. oleifera formed the zone of inhibition of 8 mm at 20 µL volume [33]. In another study, the distilled water extract had no zone of inhibition against S. aureus, whereas methanolic extract had zones of inhibition of 10 mm, 9 mm, 15 mm, and 17 mm at volumes ranging from 20 to 50 µL [32]. The chloroform extract of M. oleifera formed inhibitory zone of 10 mm at 20 µL volume against S. aureus [33].

Figure 4: Zone of inhibition shown by (a) ethanol (b) distilled water (c) methanol and (d) chloroform extracts of M. oleifera leaves against E. coli.

Figure 5: Zone of inhibition shown by (a) ethanol (b) distilled water (c) methanol and (d) chloroform extracts of M. oleifera leaves against S. aureus.

Table 5 and Table 6

The maximum inhibitory zone of 27 mm was shown by methanol extract of leaves of M. oleifera as indicated in Table 6.

The present study focuses on the various phytochemical constituents in Moringa oleifera and their anti-bacterial activity. According to our study, the seed and leaf extracts of Moringa oleifera inhibit the growth of various organisms like E. coli and S. aureus. Extracts of plant seeds and leaves could thus be utilized to treat infectious disorders caused by microorganisms. These extracts are likely to be promising natural antibacterial agents with uses in the management of bacteria that cause disease.

The financial support from Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Govt. of India, to Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla, India, is thankfully acknowledged.

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

The authors declare that no funds, grants or other support were received during preparation of this manuscript.

Copyright: © 2024 Reena Gupta., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.