Carlos Alberto Cabrini Junior1, Gabriela Meira Salomão Ambrizzi2, Munir Salomão2, Luciano Mayer3 and Irineu Gregnanin Pedron4*

1Undergraduate Student, Universidade Cruzeiro do Sul, São Paulo, Brazil

2DDS, Independent Researcher, São Paulo, Brazil

3Professor and Head, Department of Periodontology, Implantology, Oral Surgery, Dental Prosthesis and Laser, AGOR, Porto Alegre, Brazil

4DDS, MDS, Professor and Independent Researcher, Private practice, São Paulo, Brazil

*Corresponding Author: Irineu Gregnanin Pedron, DDS, MDS, Professor and Independent Researcher, Private practice, São Paulo, Brazil.

Received: July 16, 2024; Published: August 16, 2024

Citation: Irineu Gregnanin Pedron.,et al. “Integrated Management of a Fractured Tooth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Report". Acta Scientific Dental Sciences 8.9 (2024):15-20.

In addition to the stomatological manifestations resulting from COVID-19, several others were and still are observed in the dental clinic. Even today, a large number of teeth fractured at that time can be seen as a result of parafunctional habits such as bruxism and clenching, caused by the stress and anxiety experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this article is to present the integrated treatment required to rehabilitate a tooth fractured during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of bruxism. The tooth had to be extracted and a polypropylene membrane used on the alveolus to preserve the remaining alveolar bone. Subsequently, the osseointegrated implant and prosthesis were installed.

Keywords: COVID-19; Implant Dentistry; Tissue Regeneration; Bone Regeneration; Oral Surgery

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, several conditions and pathologies have been observed by the world's population as a result of coronavirus infection. Likewise, numerous stomatological changes have been observed [1]. Hyposmia; anosmia; hypogeusia; ageusia; salty taste; necrotising periodontal disease; stomatitis; aphthous ulcerations; angular cheilitis; mucositis; herpetiform lesions; candidiasis; geographic, fissured or depapillated tongue; erythema multiforme-like lesions; atypical Sweet's syndrome lesions; Kawasaki-like lesions; Melkerson-Rosenthal syndrome; bullous angina; stomatological and facial neuropathies; have been described [1-6].

In addition, other conditions such as stress, opportunistic infections, immunosuppression, poor oral hygiene and a hyperinflammatory response are predisposing factors for the appearance of stomatological lesions in COVID-19 patients [5]. Stress, as the main cause of parafunctional habits such as bruxism and clenching, is still being realized today. And subsequently, these parafunctional habits, with excessive chewing forces, have caused an increase in the incidence of dental fractures [1,7-9].

Various therapeutic and rehabilitative modalities can be used in these cases. From more conservative treatments, with maintenance and rehabilitation of the traumatised tooth using adhesive restorative procedures, to tooth extraction with future implantoprosthetic rehabilitation. In addition, therapeutic procedures such as the application of botulinum toxin in cases of bruxism and symptomatic clenching and the use of occlusal splint may be necessary [7,10-15].

The purpose of this article is to present the integrated treatment required to rehabilitate a tooth fractured during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of bruxism. The tooth had to be extracted and a polypropylene membrane used on the alveolus to preserve the remaining alveolar bone. Subsequently, the osseointegrated implant and prosthesis were installed.

A Caucasian female patient, 58-years-old, attended the dental clinic complaining of a fractured tooth.

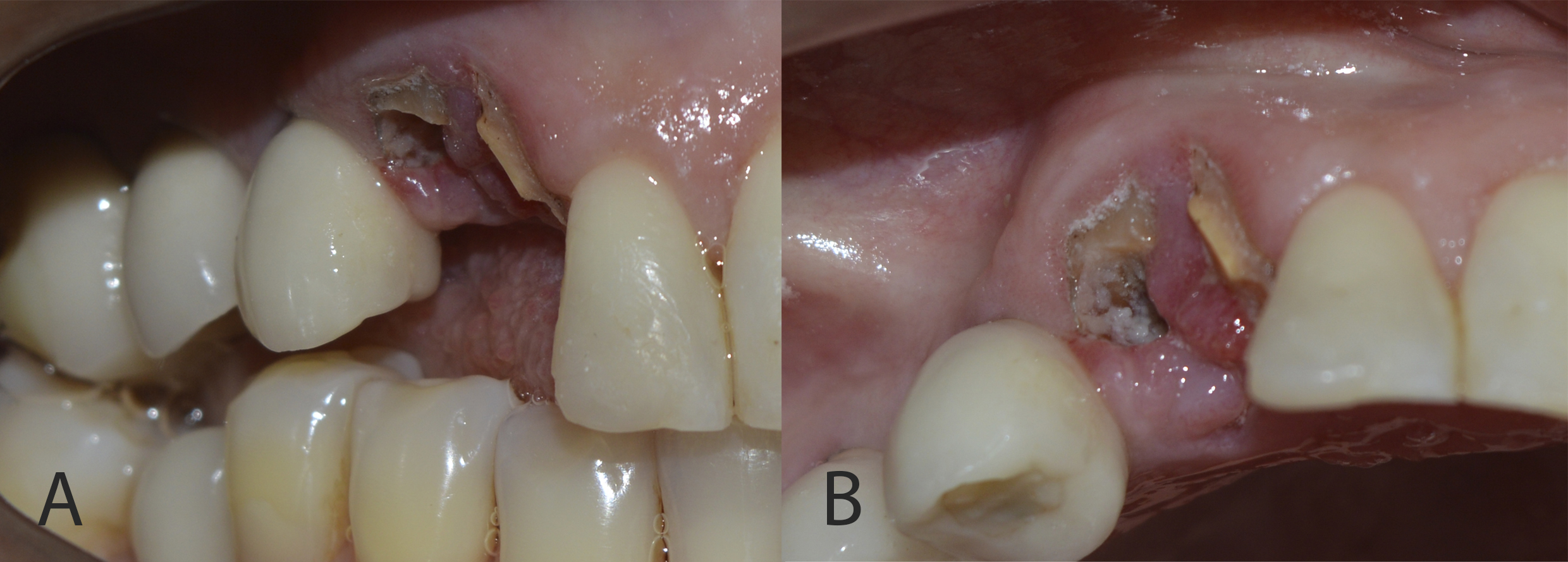

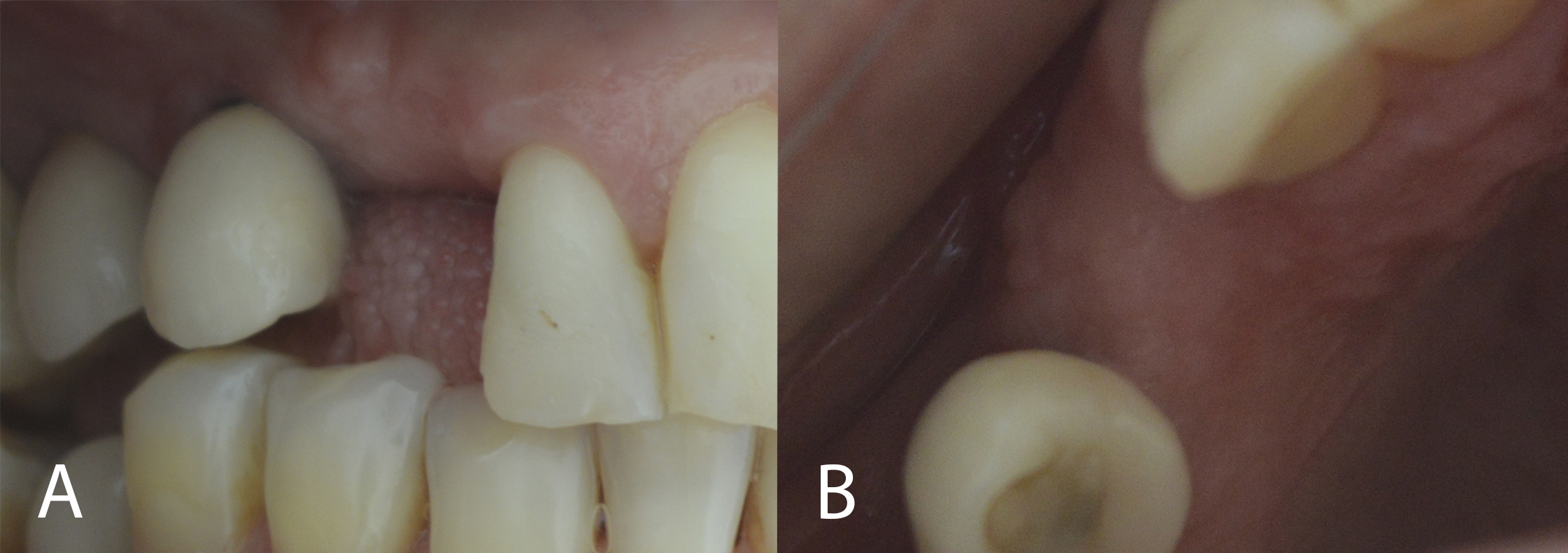

Clinically, the patient had a fracture of the upper right canine at the cervical level (Figure 1). The root remnant showed caries and inflamed adjacent gingival tissue (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Upper right canine fractured at the cervical level (frontal view).

Figure 2: Root remnant showed caries and inflamed adjacent gingival tissue (A: right lateral view; B: occlusal view).

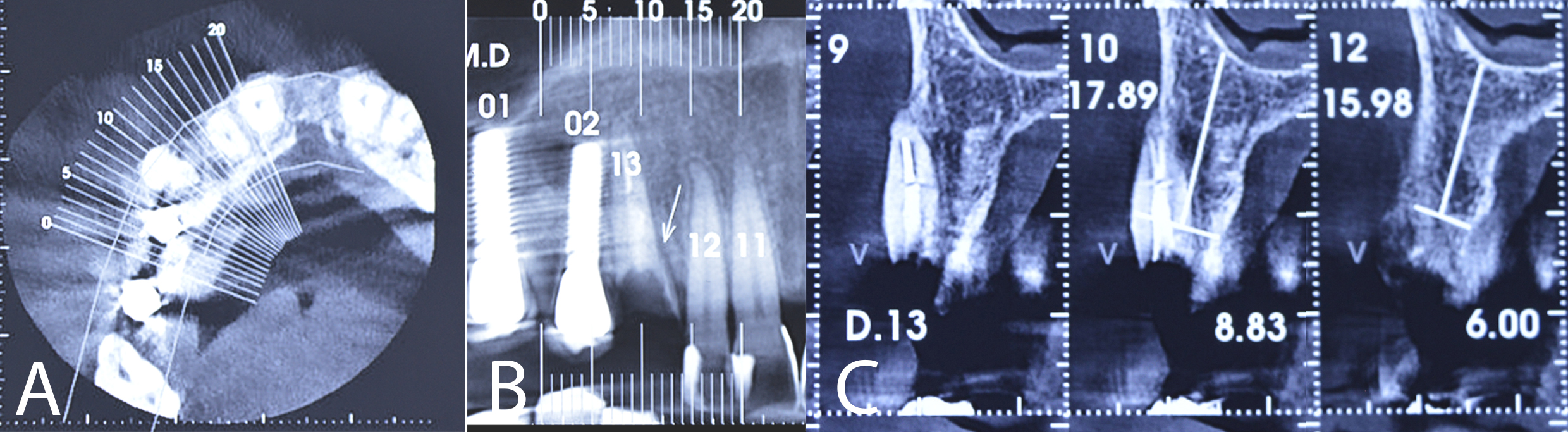

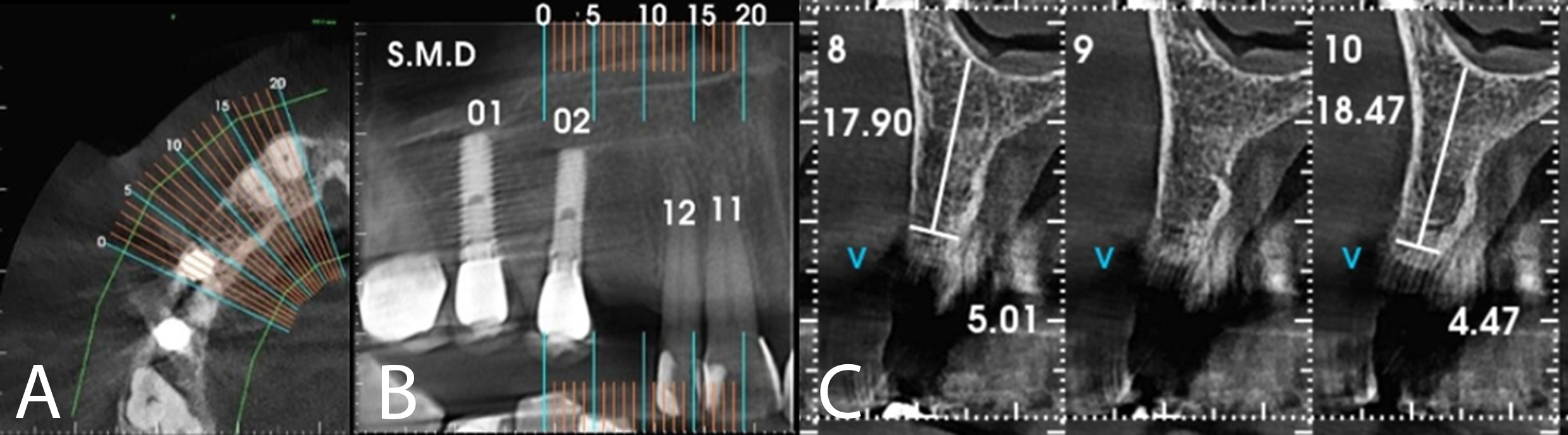

Cone beam computed tomography revealed a fracture line in the middle third of the canine root and resorption of the buccal cortex. As it was impossible to maintain the remaining root, measurements were taken for the delayed installation of an osseointegrated implant (Figure 3).

Figure 3: CBCT showing the middle third of the canine root fractured (A: axial view; B: panoramic view; C: parasagittal view).

However, at this stage, the use of a polypropylene membrane was suggested for bone preservation and future installation of the osseointegrated implant. The patient signed a consent form agreeing to the procedures.

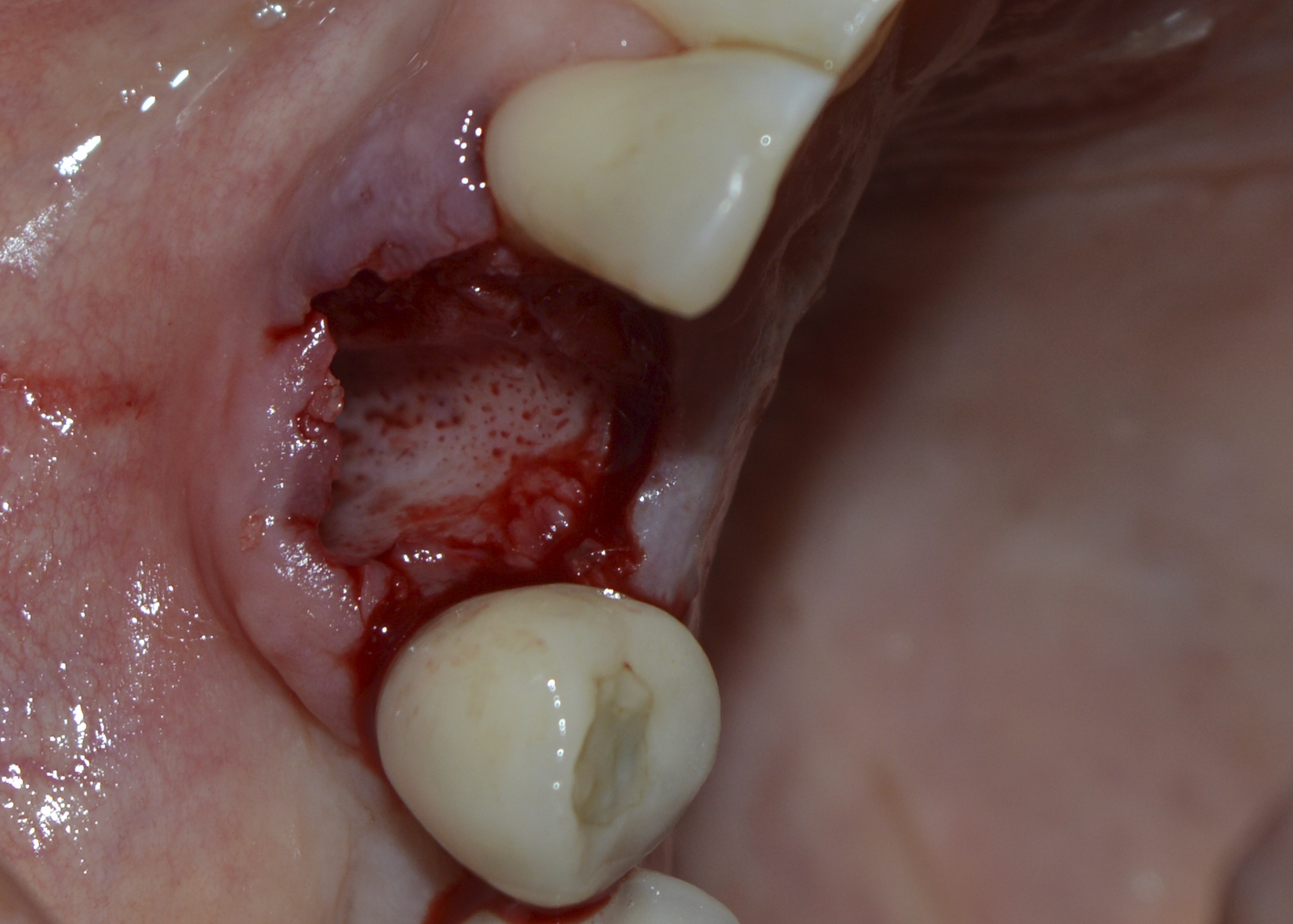

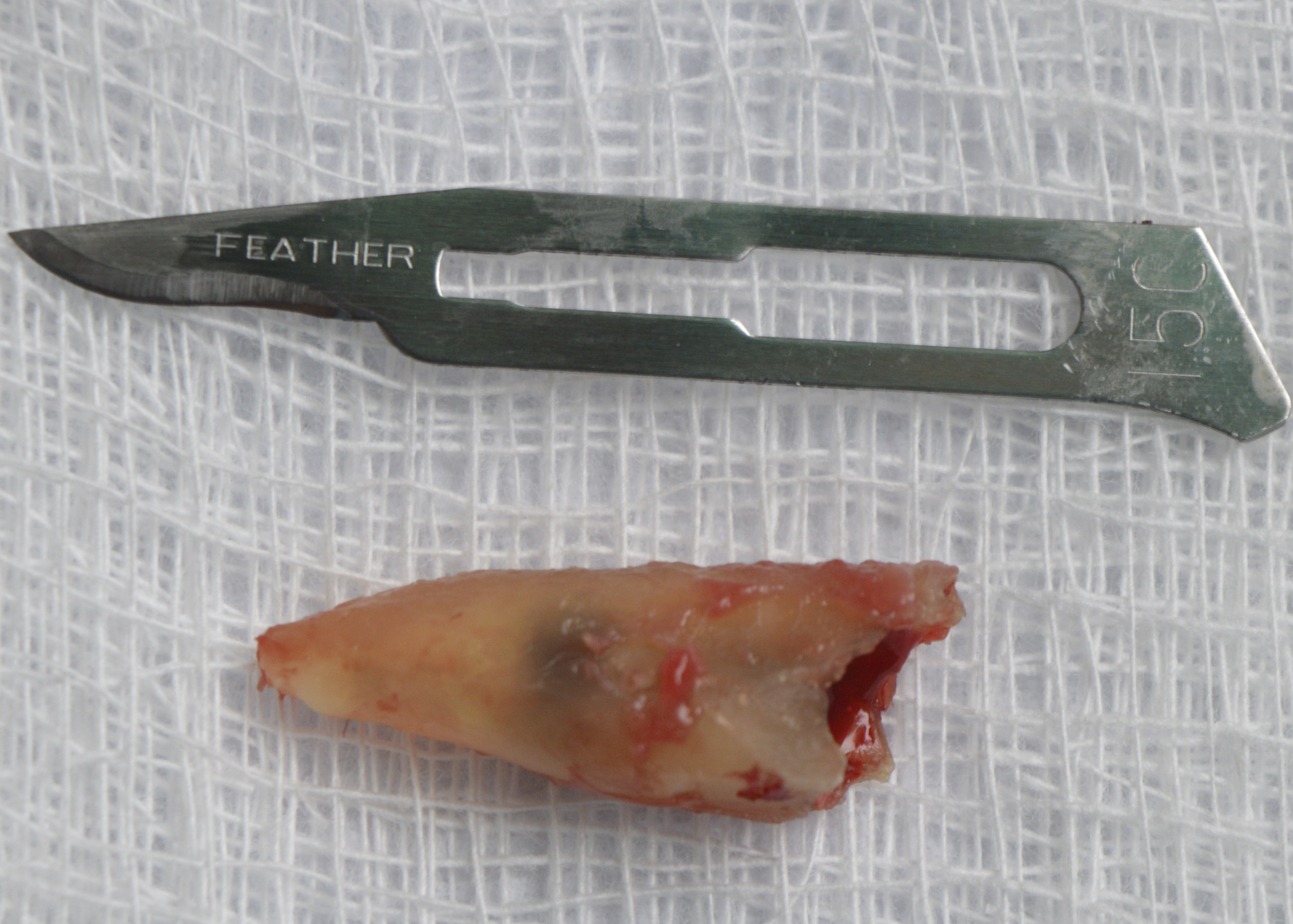

Under local anaesthesia, the right upper canine was extracted, taking care to preserve the remaining bone structure. After curettage and washing of the socket with saline solution, the bleeding necessary for blood clot formation was observed (Figure 4). The polypropylene membrane (Bone HealTM, São Paulo, Brazil) was cut and adapted to the region, being installed over the socket and under the sutures. The sutures were made without excessive traction, with the polypropylene barrier remaining exposed to the oral environment (Figure 5). The extracted root remnant showed caries and a crack (Figure 6). The patient was given analgesics, anti-inflammatories and antibiotics.

Figure 4: Socket after extraction, curettage and washing with saline solution. Observe bleeding points.

Figure 5: Polypropylene membrane installed over the socket and under the sutures.

Figure 6: Extracted root remnant showed caries and a crack.

After 15 days, the remaining sutures and the polypropylene membrane were removed (Figure 7). No complaints or complications were reported.

Figure 7: Post-operative evaluation (15 days): removal of the remaining sutures and the polypropylene membrane.

The patient was assessed 30 days after the surgery and still showed incomplete tissue repair, although bone thickness and gingival tissue were preserved (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Clinical evaluation (30 days): incomplete tissue repair.

After 8 months, the patient was assessed for continuity of treatment. Clinically, complete tissue repair and bone thickness were observed, as well as the maintenance of gingival tissue. No gingival tissue retraction was observed (Figures 9 and 10). Computed tomography revealed the preservation of mature, healthy bone tissue, necessary for the installation of the osseointegrated implant (Figure 11).

Figure 9: Clinical evaluation (8 months): bone thickness maintenance of gingival tissue (frontal view).

Figure 10: Clinical evaluation (8 months): bone thickness maintenance of gingival tissue (A: right lateral view; B: occlusal view).

Figure 11: CTCB showing preservation of mature, healthy bone tissue.

Under local anaesthesia, an 3.5 X 15mm Morse Cone implant (SINTM, São Paulo, Brazil) was installed. All post-surgical care was taken as previously reported. The patient progressed well, with no complaints or complications.

After 6 months, the area was opened and the healing abutment installed (Figure 12). The patient was subsequently moulded, the metal infrastructure made, the colour taken, the occlusal records and the ceramic tried in. Finally, the porcelain prosthesis was installed (Figures 13 and 14). The case has been followed up for 2 years.

Figure 12: Instalation of the healing abutment.

Figure 13: Instalation of the porcelain prosthesis (frontal view).

Figure 14: Instalation of the porcelain prosthesis (lateral view). Observe the preservation of the gingival tissue.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, dental surgeons still strive for efficient dental care, complying with health and biosafety requirements. In addition, every clinical and scientific aspect to benefit patients must be considered [1].

In this perspective, increasingly conservative techniques, particularly when implant prosthetic rehabilitation is envisaged, benefit procedures and patients.

The maintenance and stabilisation of the blood clot within the dental alveolus or bone cavity is extremely necessary for bone neoformation. Bone and tissue regenerative techniques should be used after extraction with a view to future implant prosthetic rehabilitation. In association, more careful and gentle techniques can also help to preserve the remaining tissues. Various techniques may or may not be used in regenerative techniques. However, it should be borne in mind that most of these biomaterials compete with blood and/or blood clots. In addition, most of the time, biomaterials should not be exposed to the oral environment, running the risk of contamination and infection at the surgical site. From this perspective, the polypropylene membrane was developed to meet these needs, with the added advantage of being able to be exposed to the oral environment. It maintains and immobilises the blood clot after tooth extraction [16-31].

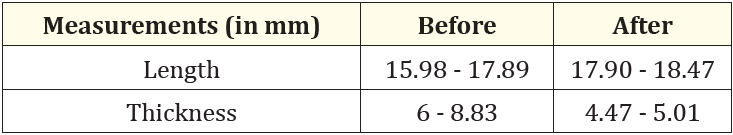

Table 1 summarises the measurements observed in the tomographic sections before and after using the polypropylene membrane in the tooth extraction. Although the thickness measurements were lower after extraction of the fractured canine, the composition of the buccal cortical bone, which was not observed before, is clearly visible (Figures 3 and 11, respectively).

Table 1: Comparison between measurements before and after the use of a polypropylene membrane in the tooth extraction.

Thus, the use of polypropylene membranes is widely presented in the dental literature [16-31]. Its use includes various indications: extractions with immediate [16-24] and late implants [25]; in osseous cavity after the removal of cystic lesions [26,27]; in maxillary sinus lifting [28]; in bone regeneration in cases of perimplantitis [29] and screw explantation [30]; and in gingival preservation, protecting perimplant tissue [31].

Four years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is still possible to observe pathological conditions that began during this period. Parafunctional habits such as bruxism and clenching, manifested by the stress and anxiety experienced during the pandemic, have often led to dental trauma. When it is impossible to maintain the dental element and considering extraction, regenerative procedures can and should be used to preserve the remaining bone, with a view to the future installation of osseointegrated implants. From this perspective, the use of a polypropylene membrane was effective in preserving bone tissue for the subsequent installation of osseointegrated implants.

Copyright: © 2024 Pratiksha Dhungana. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ff

© 2024 Acta Scientific, All rights reserved.