Semir Abdi Usmael* and Teferi Merid Seyoum

Department of Internal Medicine, Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Science, Harar, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Semir Abdi Usmael, Department of Internal Medicine, Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Science, Harar, Ethiopia.

Received: July 15, 2024; Published: September 19, 2024

Citation: Semir Abdi Usmael and Teferi Merid Seyoum. “Sudden Cardiac Death Due to Ciprofloxacin Induced Torsade De Pointes". Acta Scientific Clinical Case Reports 8.10 (2024):33-37.

Introduction: Fluoroquinolone is a commonly used antibiotic due to its broad spectrum activity. However, evidence suggests this class of drug causes QT-interval prolongation and torsade de Pointes. Ciprofloxacin is considered to be safer than other agents in this class in terms of QT-interval prolongation and torsade de pointes.

Case Presentation: a 40-years old male patient with no previous cardiac history presented with profuse watery diarrhea, hypotension, tachycardia, cold extremities, and delayed capillary refill. Laboratory work-up revealed severe hypokalemia and elevated serum creatinine. Within 16 hours of administration of intravenous ciprofloxacin, the patient died due to recurrent cardiac arrest secondary to torsade de pointes.

Conclusion: cardiac arrest due to torsade de pointes in the acquired form of drug-induced Long QT syndrome is a rare but potentially catastrophic event. Even though ciprofloxacin is considered to be the safest agent in this class, it can cause QT-interval prolongation, torsade de pointes, and sudden cardiac death, especially in the presence of predisposing factors. This case emphasizes the importance of prevention, early recognition, and treatment of QT-interval prolongation and torsade de pointes induced by ciprofloxacin.

Keywords: Ciprofloxacin; Prolonged QT-interval; Torsade de Pointes; Acquired Long QT Syndrome; Fluoroquinolone

ECG: Electrocardiogram; IV: Intravenous; LQTS: Long QT Syndrome; SCD: Sudden Cardiac Death; TdP: Torsade De Pointes; VT: Ventricular Tachycardia

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a disorder of myocardial repolarization characterized by a prolonged QT interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG). This syndrome is associated with an increased risk of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and a characteristic life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia also known as torsade de pointes (TdP). TdP is an uncommon and fatal polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia, which often occurs in association with a prolonged QT interval. It is usually asymptomatic and terminates spontaneously; nevertheless it can cause syncope, dizziness, palpitations, seizures, and sudden cardiac death (SCD).

QT prolongation has traditionally been separated into two general categories: congenital LQTS and acquired LQTS. The acquired causes include drugs (antiarrhythmic, antibiotic, antipsychotic, antihistamines, and antiemetic), electrolyte abnormality (hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia), bradycardia, ischemia, stroke, and structural heart disease [1-3].

Quinolone antibiotics are frequently prescribed agents due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy. QT prolongation is a class effect of fluoroquinolones, but there are great differences between the various members of this group in their proarrhythmic potential. Ciprofloxacin is considered to be safer than the other agents in this class [4]. Current clinical studies suggest that among quinolones, ciprofloxacin has no effect on QT interval in healthy subjects with no predisposing factors [5,6] and a weak effect in patients with preexisting risk factors for torsade de Pointes [4,7].

We report a case 40-years old Ethiopian man with no previous history of cardiac disease who died due to recurrent cardiac arrest secondary to ciprofloxacin-induced torsade de pointes.

A 40-year-old Ethiopian man with no previous history of cardiac disease presented with a 7-days history of profuse watery diarrhea associated with vomiting and crampy abdominal pain. He denied a history of shortness of breath, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and palpitation. He had no family history of sudden cardiac death and cardiac illness.

On physical examination, the patient appeared acutely ill and his vital signs were as follows: blood pressure (BP)-70/50 mmHg, pulse rate (PR)-104 beat per minute which was feeble, respiratory rate-20, temperature- 35-degree Celsius, and saturation of 96% on room air. There was conjunctival pallor. There were signs of peripheral hypoperfusion such as cold extremities and delayed capillary refill. Cardiac and nervous system examinations were non-revealing.

Laboratory work-up revealed; serum potassium: 2.27mmol/L, sodium: 127mmol/L, chloride: 99.7mmol/L, serum creatinine: 2.33mg/dl, and blood urea nitrogen: 108.8 mg/dl. White cell count (WBC) level was 8800 and Hemoglobin (Hgb) was 10.2 g/dl. Liver enzymes were within the normal range and total and direct bilirubin level was 1.62 mg/dl and 1.05 mg/dl, respectively. There were numerous puss cells on microspic stool exam. Blood and stool culture were sent.

With this finding, a working diagnosis of septic shock of GI focus, acute kidney injury, severe hypokalemia, and hypovolemic hyponatremia was established.

The patient was admitted and managed as follows: intravenous (IV) epinephrine infusion was started after BP failed to respond to initial fluid resuscitation, IV ceftriaxone 1 gram BID and metronidazole 500 mg TID, IV potassium chloride infusion 40 meq in 400 ml of normal saline TID, and Oral rehydration solution 300 ml per loss.

Despite the above management, there was poor clinical response, and laboratory work-up 2 days after admission revealed a high WBC level (28, 080) and Hgb level of 6.2 g/dl. Serum potassium become 3.72 mmol/l. There was no growth on blood and stool culture. Subsequently, the initial antibiotics were discontinued and IV ciprofloxacin 400 mg BID and vancomycin 1g BID was initiated. He was transfused with 2 units of packed red blood cell and given IV hydrocortisone 100mg TID. IV potassium chloride infusion was discontinued. The remaining treatment was continued.

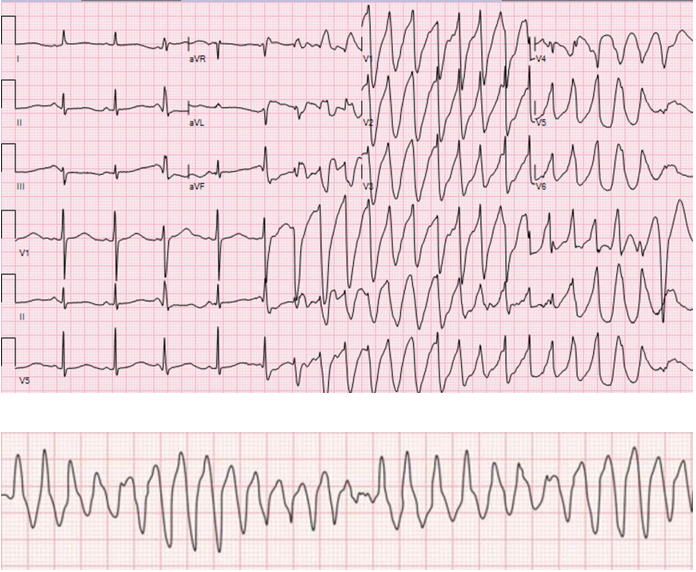

Within 16 hours of ciprofloxacin initiation, he developed sudden onset shortness of breath followed by loss of consciousness. On examination, he was unresponsive, pulse was not palpable, BP was unrecordable, and had no spontaneous breathing effort. The random blood sugar level was 195 mg/dl. ECG done at this time revealed a sustained polymorphic tachycardia with a feature of torsade de pointes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: ECG taken during episode of cardiac arrest showing feature of Torsade de pointe: initiation of the arrhythmia after a short-long-short cycle sequence PVC that falls near the peak of the distorted T-wave, irregular RR interval, and abrupt switching of QRS morphology from predominately positive to predominately negative complexes (A). Note the change in polarity of QRS complex about the isoelectric line (B).

With a diagnosis of sudden cardiac arrest due to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia induced by ciprofloxacin, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was started immediately; epinephrine infusion at a rate of 0.3 microgram/kg/minute commenced and amiodarone 150 mg IV bolus was administered. After 5 cycles of CPR and defibrillation return of spontaneous circulation was achieved. However, 30 minutes later he developed additional episodes of recurrent torsade de pointes and cardiac arrest. CPR and defibrillation were attempted but it was not successful and the patient passed away. The possible cause of death was cardiac arrest secondary to torsade de pointes induced by ciprofloxacin.

Fluoroquinolones are commonly used antimicrobial agents because of their wide antimicrobial efficacy in common respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary infections. However, cardiac toxicity can occur as an unintended consequence of therapy with quinolone. Case reports and other studies have reported several quinolone-induced arrhythmia-related cardiac effects, including QT interval prolongation, TdP, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and SCD [4,8,9]. Fluoroquinolones prolong the QT interval by blocking the cardiac voltage-gated rapid potassium channels (IKr). This adverse effect can be potentiated by the presence of predisposing factors such as female gender, structural heart disease, concomitant use of QT-interval-prolonging medication, reduced drug elimination (due to drug interaction, renal, or hepatic dysfunction), electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia), bradycardia, prolonged QTc interval before therapy, and congenital LQTS.

The risk of QT prolongation and TdP varies among quinolones; moxifloxacin appears to have the greatest risk followed by levofloxacin and ofloxacin. Ciprofloxacin has been associated with the lowest risk for QT prolongation and torsade de pointes [4-6,9,10]. Even though ciprofloxacin is considered to be the safest quinolone in terms of TdP, there are several case reports on ciprofloxacin-induced TdP [11-15]. This case report suggests that ciprofloxacin should be used with great caution in patients who are at risk for QT prolongation and QT-mediated arrhythmias.

The diagnosis of quinolone-induced TdP requires the presence of a clear temporal relationship between exposure and onset of the ECG features. Typical ECG features of TdP include an antecedent prolonged QT interval, particularly in the last heartbeat preceding the onset of the arrhythmia. Additional typical features include a ventricular rate of 160 to 250 beats per minute, irregular RR intervals, and cycling of the QRS axis through 180 degrees every 5 to 20 beats. In our case, TdP developed within 16 hours of ciprofloxacin administration and the patient had predisposing factors such as hypokalemia and acute kidney injury.

Prevention of ciprofloxacin-induced QT-interval prolongation and TdP in a high-risk patient includes, whenever possible alternative antibiotics that don’t prolong QT interval should be used, serum potassium and magnesium should be maintained in the normal range, and monitoring the QT-interval before and at least every 8 to 12 hours after initiating the drug [16].

The management of quinolone-induced QT-interval prolongation includes discontinuation of the offending drug and aggressive correction of any metabolic and electrolyte abnormalities. Prompt defibrillation in hemodynamically unstable and in those with syncope due to torsade de pointes. In conscious patients’ treatment with intravenous magnesium infusion, beta-blockers, and temporary transvenous pacing are indicated [17].

The major limitations in the management of this case were; initiation of full dose of ciprofloxacin in the presence of acute renal failure and severe hypokalemia, inadequate monitoring of QT interval after starting culprit drug, failure to withdraw ciprofloxacin, and inappropriate treatment of TdP namely failure to administer IV magnesium sulfate and inappropriate administration of IV amiodarone. Since there is no baseline ECG before administration of ciprofloxacin, congenital LQTS can’t be ruled out completely.

Cardiac arrest due to TdP in the acquired form of drug-induced LQTS is a rare but potentially catastrophic event. Although fluoroquinolone is well tolerated, and effective, they are associated with various cardiac toxicities. Even though ciprofloxacin is considered to be the safest agent in this class, it may cause QT-interval prolongation, torsade de pointes, and sudden cardiac death, especially in the presence of predisposing factors. This case emphasizes the importance of prevention, early recognition, and treatment of QT-interval prolongation and TdP induced by ciprofloxacin.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying image. A copy of written consent is available for review by an editor in chief of this journal.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interest.

None.

Not applicable.

We thank the patient and her family for information provided and their approval for publication of this case.

SA and TM contributed to the acquisition of history, laboratory investigation, and interpretation of the case and the patient data. SA carried out a literature review and was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Copyright: © 2024 Semir Abdi Usmael and Teferi Merid Seyoum. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.